Want to receive Best Practice Bulletin directly to your inbox?

Sign up here.

Want to receive Best Practice Bulletin directly to your inbox?

Sign up here.

Published: 25th July, 2025

Contents

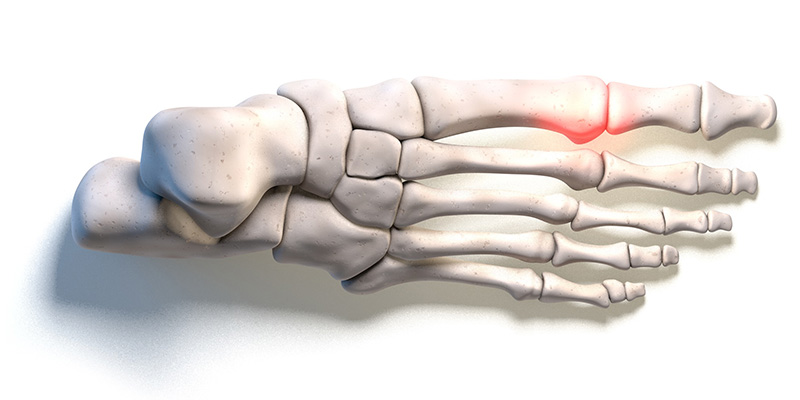

New from bpacnz: Gout case study quiz

bpacnz recently published an article on the diagnosis and management of gout. Gout is highly treatable with regular urate-lowering medicine use, but many people do not seek, or receive, the level of management they require. Beyond the acute treatment of flares, primary healthcare professionals can help establish strategies for long-term prevention. Urate-lowering medicines should be considered and discussed with all patients who have gout from the first presentation, even if not immediately prescribed. Allopurinol is first line, but other treatments can be added or used alternatively, if targets are not achieved.

A case study quiz has now been developed to accompany this article. It follows the story of Malo Fuimaono, a 47-year-old male who presents with severe pain in his right big toe. What can you do to help Malo? Do you feel confident that you can set Malo on a positive path towards long-term symptom control?

Can you help Malo? Also test your knowledge on our “extra for experts” question. Complete the case study quiz here.

N.B. You will need to log-in to “My bpac” or create a free account. Quizzes are endorsed as a professional development activity by the RNZCGP (two CPD credits) and InPractice; a certificate of completion is also provided for all participants.

Read the full article on gout, here. A B-QuiCK summary, clinical audit and peer group discussion are also available.

In case you missed it: Recommended vaccinations for healthcare workers

Healthcare workers are exposed to many vaccine-preventable diseases in their day-to-day work, so must maintain full immunisation coverage. Vaccination not only helps to reduce personal disease risk for the healthcare worker but may also lower the risk of transmission to patients. Read the full article here.

Healthcare workers are exposed to many vaccine-preventable diseases in their day-to-day work, so must maintain full immunisation coverage. Vaccination not only helps to reduce personal disease risk for the healthcare worker but may also lower the risk of transmission to patients. Read the full article here.

New Zealand Clinical Principles Framework for ADHD

The Ministry of Health has published the New Zealand Clinical Principles Framework for ADHD. The framework, which is based on international guidelines, details the expected standards for the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of children, young people and adults with ADHD. The Ministry of Health has designed the framework to ensure quality, safety and consistency for clinicians when assessing and managing patients with ADHD.

The standards include information on what should be covered as part of the comprehensive assessment, treatment and management plan, pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments, monitoring requirements and reviewing treatment response. The framework states that vocationally registered general practitioners and nurse practitioners “who have developed further clinical expertise in ADHD” are appropriate healthcare professionals to assess and diagnose ADHD in adults. This includes training in diagnostic assessment of ADHD and experience conducting clinical interviews and administering and interpreting clinical assessment tools related to ADHD. However, no information is given on how this training will be provided for clinicians who do not already have this expertise, or on how the comprehensive assessment process can be accommodated and funded within primary care.

The framework has been developed in collaboration with clinicians who have experience in ADHD assessment and treatment, as well as people with lived experience of ADHD.

Read the full framework, here. Click here to read the principles for children and young people, or here for adults.

Medicine news: Duolin, continuous glucose monitors, Soframycin

The following news relating to medicine supply has recently been announced. These items are selected based on their relevance to primary care and where issues for patients are anticipated, e.g. no alternative medicine available or changing to the alternative presents issues. Information about medicine supply is available in the New Zealand Formulary at the top of the individual monograph for any affected medicine and summarised here.

Supply issues affecting salbutamol with ipratropium bromide inhalers (Duolin HFA) remain ongoing. Prescribing a salbutamol inhaler (SalAir) and ipratropium bromide inhaler (Atrovent) may be a suitable alternative, however, two new prescriptions will be required. Pharmac has temporarily removed the co-payment on ipratropium bromide inhalers meaning that patients who require both inhalers will only pay one dispensing fee (for SalAir).

The FreeStyle Libre 2 Plus continuous glucose monitor (CGM) has been funded since May, 2025, for patients with type 1 or type 3c diabetes (as reported in Bulletin 121). This device is an upgraded version of the FreeStyle Libre 2 model, and can be worn for an additional day (15 instead of 14), and is considered more accurate. Stock of the FreeStyle Libre 2 will no longer be supplied from 1st November, 2025. Pharmacies can submit claims up until 1st May, 2026, when the product will be delisted from the Pharmaceutical Schedule.

Patients prescribed the FreeStyle Libre 2 can begin to be switched to the new device now, to avoid a rush on devices in November. When a patient next presents for their CGM renewal, specify on the prescription “FreeStyle Libre 2 Plus”, so that this brand can be dispensed. Special Authority criteria remain the same (a new application is not required).

Pharmac has advised that framycetin sulphate 0.5% ear/eye drops (Soframycin; partly funded), used in the treatment of otitis externa when a steroid is not required, are out of stock due to higher than anticipated demand. Re-supply is expected in August. Funded alternatives are available (click here for details), however, a new prescription will be required.

Shingrix funding

In a recent email to the sector, the Immunisation Advisory Centre (IMAC) is reminding healthcare professionals that if patients received their first dose of Shingrix at age 65 years, the second dose will also be funded regardless of the timing between doses. The ideal timing between doses is two to six months but a repeat of the first dose is not needed if the interval exceeds six months.

The Aotearoa Immunisation Register (AIR) does not differentiate between shingles vaccines. Shingrix became the funded brand in 2022 (as reported in Bulletin 56). The previously funded brand, Zostavax, was a single dose vaccine. Therefore, people who received shingles vaccination prior to 2022 are likely to have received Zostavax. A previous dose of Zostavax does not count towards a Shingrix course. Further information on Shingrix is available from IMAC, here.

In Brief: Consultation on topical corticosteroid labelling extended

Medsafe is seeking feedback on a proposal to include warning statements about potency on the medicine packaging for topical corticosteroids (as reported in Bulletin 126). The closing date for this consultation has been extended to Wednesday, 13th August, 2025. This link contains an online form to complete.

Medical Council: New medical training survey + further changes to registration pathway for overseas doctors

The Medical Council of New Zealand has announced the establishment of Torohia, an online survey for doctors in training across New Zealand. The survey will be open for a three-week period each year, between August and September; this year it will be launched on Monday, 18th August and will close on Monday 8th September. Doctors in accredited prevocational and vocational training programmes are eligible to participate (non-training registrars will be able to take part in the survey from 2026). Responses are confidential and anonymous. A summary of the results will be available in December; detailed findings will be published in February. A toolkit containing a factsheet about the survey and other resources is available here.

In a separate news release, the Medical Council announced further changes to the registration pathway for international medical graduates. Key changes include:

- A fast-track registration process for general practitioners who trained in the USA, Canada or Singapore

- Doctors with recent clinical experience in Chile, Luxembourg and the Republic of Croatia will be eligible to apply for provisional general registration via the Comparable Health System pathway

- Shorter processing times for applications from overseas-trained specialists

Read more here.

Upcoming webinars: Heart failure, antibiotics, joint pain, weight management, chronic pain

HealthPathways is hosting a national webinar on heart failure management in the community. This free webinar is expected to cover the four pillars of heart failure treatment, including medicines titration, as well as non-pharmacological management with a focus on nurse-led community clinics. The webinar will be held on Tuesday, 12th August, from 7 – 8 pm. Click here to register (a certificate of attendance and two CPD points are available). A recording will be available at a later date.

For further information on the diagnosis and management of heart failure in primary care, see: https://bpac.org.nz/2025/heart-failure.aspx

The Goodfellow Unit, University of Auckland, is hosting several free access webinars in the coming months. These webinars are intended to provide topical and relevant health information for primary care clinicians. CPD points are also available. Webinars are often recorded and available to watch at a later date. Upcoming webinars include:

- Antibiotics: DoxyPEP, plus the national antibiotic guidelines, a Te Whatu Ora; Te Tiri Whakāro: Sharing Knowledge session:

- Dr Jeannie Oliphant will provide an overview of the DoxyPep guidelines

- Dr Stephen Ritchie will discuss the development of Te Whata Kura, the new national antibiotics guidelines

- Dr Sue Tutty will provide clinical updates

This webinar will be held on Tuesday, 29th July, from 7.30 – 8.45 pm. Click here to register.

Practice Focus: Prostate cancer screening – to DRE or not to DRE?

Practice Focus: Prostate cancer screening – to DRE or not to DRE?

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in males in New Zealand, and the second most common cause of cancer-related mortality. Performing a digital rectal examination (DRE) for prostate cancer screening is often considered best practice in New Zealand, alongside PSA testing. However, recommendations vary between international guidelines. An article published in the British Journal of General Practice (BJGP) last year questioned the value of DRE in prostate cancer screening and raised concerns about the procedure representing a barrier to males seeking care for prostate-related issues. The British Association of Urological Surgeons in association with Prostate Cancer UK, has since issued a statement (June, 2025), that DRE is no longer considered a useful screening test for prostate cancer. There have been no changes to the recommendations in New Zealand at this stage.

Read more

There is a lack of evidence regarding the utility of DRE as a routine screening test for prostate cancer. A DRE only assesses the back wall of the prostate gland; abnormalities elsewhere in the gland cannot be manually detected. DREs may also represent a barrier for males discussing prostate concerns with their clinician or in some cases, attending primary care in the first place; in a survey of over 2,000 males in the UK, 60% reported concerns about having a rectal examination. These concerns were sufficient to prevent 37% of these males discussing prostate issues with their general practitioner. There was also variation in the levels of cultural stigma around DRE between different ethnic groups, which must be balanced against the increased risk of diagnosis and death from prostate cancer in these groups. In New Zealand, people of Māori and Pacific ethnicity are more likely to be diagnosed with and die from prostate cancer than non-Māori, non-Pacific peoples.

The authors of the BJGP article recommend that healthcare professionals ask themselves “will DRE change my clinical decision making?” when deciding whether or not to perform a DRE. The authors emphasise the importance of considering DRE if clinical suspicion persists following a negative PSA test result, particularly in patients with risk factors, e.g. family history of prostate cancer. Under these circumstances, DRE may be useful in detecting a proportion of the 2% of prostate cancers that do not produce PSA and may therefore otherwise remain undetected; an estimated 20% of prostate cancers that do not produce PSA are detected through an abnormal DRE result. DRE also has value in detecting benign prostatic conditions, such as prostatitis, in patients who are symptomatic, e.g. those with pelvic or genitourinary pain and lower urinary tract symptoms.

This advice does not align with the New Zealand Prostate Cancer Management and Referral Guidance (2015), which recommends both PSA testing and DRE for males aged over 50 years, or over 40 years with a family history of prostate cancer, who present with prostate concerns. However, the guidance does acknowledge that some males may be averse to DRE, in particular those of Māori and Pacific ethnicity for whom there may be an additional cultural barrier, and that this should not represent a barrier to prostate cancer screening. A pragmatic approach may be to perform PSA testing prior to DRE. In the event of an abnormal initial PSA result, a repeat test should be performed 6 – 12 weeks later; referral is usually warranted following two abnormal PSA results even in the absence of a DRE result, e.g. if DRE is declined. Individuals with normal PSA results should be informed about the value of DRE for detecting prostate cancer that does not produce PSA, particularly those with risk factors, e.g. family history of prostate cancer. Check local HealthPathways for region-specific guidance.

A UK-based blog that discusses the relevance of this BJGP review for primary care is also available here.

For further information on prostate cancer testing, including a discussion on the role of DRE, see: https://bpac.org.nz/2020/prostate.aspx

Medical Factorium: Would you like a tissue? The science of crying

Medical Factorium: Would you like a tissue? The science of crying

Every now and then, patients ask “why?” and the answer eludes us. In this occasional bulletin segment, we attempt to answer some of those curious questions.

The question: Crying is a part of our emotional toolkit, whether we like it or not; but why do we do it?

Read more

Crying is defined as the shedding of tears in response to an emotional state.1 Tears can be classified as: basal (lubrication), reflex (debris removal) and emotional.1, 2 Before the lacrimal gland was identified as the origin of tears in 1662, there were numerous theories for where tears came from. For example, emotions were heated in the heart, which then generated water vapour; this vapour would then rise to the head, and condense in the eyes, which resulted in tears.

Emotional tears occur in response to positive (e.g. kindness) or negative events (e.g. injury, pain, grief).2 The exact mechanism of emotional tear production and reasons for crying are not fully understood.2 The process of crying is believed to involve multiple components, including muscle activity, vocalisation, tear production and emotional experience.3 In response to stimuli, a signalling pathway is activated (mostly parasympathetically mediated) which results in the secretion of tear fluid by the lacrimal gland. Multiple aspects of the nervous system, areas of the brain and neurotransmitters are understood to be involved; further research is needed to determine the specific neural circuits involved in crying.3

Charles Darwin once stated that emotional tears were “purposeless”.1 Since then, multiple theories on why people cry have been proposed, with most involving communicative functions.2 Crying is thought to act as a distress signal to elicit social support.1, 3 Crying can also activate empathy and affection from others, further facilitating social connections.1, 3 The act of crying may release endorphins or oxytocin, and may affect mood in a positive or negative way.4, 5

When a patient cries during a consultation, it can sometimes be difficult to know how best to respond. A suggested approach is to allow the patient time to express their emotions for a few moments (ensure tissues are within reach), take note of your own body language and reaction, and be empathetic, sensitive and validate the patient’s feelings and situation. In many cultures and demographics, crying is viewed as a sign of weakness. It’s important to reassure all patients that it’s okay to cry and be vulnerable; after all, crying is simply a normal biological response.

References

- Sidebotham C. Viewpoint: Why do we cry? Are tears ‘purposeless’? Br J Gen Pract 2020;70:179–179. doi:10.3399/bjgp20x709049.

- Sznycer D, Gračanin A, Lieberman D. Emotional tears: What they are and how they work. Evolution and Human Behavior 2025;46:106652. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2025.106652.

- Bylsma LM, Gračanin A, Vingerhoets AJJM. The neurobiology of human crying. Clin Auton Res 2019;29:63–73. doi:10.1007/s10286-018-0526-y.

- Gračanin A, Vingerhoets AJJM, Kardum I, et al. Why crying does and sometimes does not seem to alleviate mood: a quasi-experimental study. Motiv Emot 2015;39:953–60. doi:10.1007/s11031-015-9507-9

- Bylsma LM, Gračanin A, Vingerhoets AJJM. A clinical practice review of crying research. Psychotherapy 2021;58:133–49. doi:10.1037/pst0000342.

View previous Medical Factorium items here.

Do you have a clinical oddity that you would like us to investigate, or better yet, can you share a fascinating medical fact with our readers? Email: editor@bpac.org.nz

Paper of the Week: Increased risk of type 1 diabetes in children post-COVID-19 infection

Paper of the Week: Increased risk of type 1 diabetes in children post-COVID-19 infection

It is estimated that there are around 25,000 people in New Zealand with type 1 diabetes, the majority of whom are diagnosed during childhood or adolescence. Type 1 diabetes is a life-long condition that can have a significant impact on a child and their family/whānau, both in the immediate period following diagnosis (e.g. adapting to blood sugar measurements and daily insulin injections) and in the future as the child becomes a young adult and transitions to self-management.

Type 1 diabetes occurs due to the loss of pancreatic beta cells, resulting in insulin deficiency. It can occur acutely or evolve over months or years. In most cases, it is driven by an autoimmune response, triggered by genetic or environmental factors. There is mixed evidence that viral infections, e.g. enteroviruses, are associated with the development or unmasking of type 1 diabetes in some people.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been circulating in almost all populations since March, 2020. SARS-CoV-2 infection can lead to severe acute complications, persistent symptoms, e.g. long-COVID, and has been implicated in the development of several chronic conditions, including type 1 diabetes.

A study published in Diabetic Medicine investigated whether an increase in the incidence of type 1 diabetes among children and young people in the United Kingdom (UK) during the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. It was found that the risk of being diagnosed with type 1 diabetes one to seven months following SARS-CoV-2 infection was at least 2.4 times higher, compared to those who did not test positive for SARS-CoV-2. Type 1 diabetes diagnoses in the UK have declined again post-pandemic.

It is unknown whether there has been an increase in type 1 diabetes among children in New Zealand following the COVID-19 pandemic, and it remains a relatively rare diagnosis, but it is possible that we may see more burden of disease. This study provides important information about the relationship between viral illness and the development of autoimmune disease in children. It raises awareness of type 1 diabetes as a potential differential diagnosis in children with non-specific symptoms and a history of SARS-CoV-2 or another viral illness.

Were you aware of the association between viral infections and the development of type 1 diabetes? Would you typically include type 1 diabetes in your differential diagnoses when evaluating a child with non-specific symptoms?

Read more

- This was a population-based cohort study, based on health records of people hospitalised between March, 2015, and August, 2022, in England, UK

- The exposed cohort included approximately 1,100,000 children and young people aged 0 – 17 years who first tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection between May, 2020, and August, 2022

- Four unexposed cohorts were included for comparison. These comprised of children and young people admitted to hospital either electively or due to trauma during the pandemic (May, 2020 – August, 2022) or the years beforehand (January, 2018 – December, 2019); they did not have a record of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the study period (those with chronic medical conditions were excluded)

- Type 1 diabetes diagnosis incidence was recorded at three timepoints: acute (0 – 27 days after the index date), post-acute (28 – 209 days) and late (210 days or later). N.B. The index date was the date the child or young person tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection (exposed) or the day of first admission (unexposed).

- The primary outcome of this study was diagnosis of type 1 diabetes during the post-acute period

- A diagnosis of type 1 diabetes was recorded in 2,637 children and young people across all cohorts (a further 324 had a diabetes diagnosis recorded but no type specified and 395 were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes)

- During the post-acute period, 475 of the 1,100,000 children and young people exposed to SARS-CoV-2 developed type 1 diabetes. This translated to an incidence rate per 100,000 person-years of 90.5 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 82.7 – 99.0). In comparison, the incidence rate in the trauma cohort (not exposed to SARS-CoV-2) was 37.6 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI = 25.2 – 56.2) and 29.8 (95% CI = 21.2 – 41.9) in the elective cohort (not exposed to SARS-CoV-2).

- The incidence rates in the historic cohorts were 22.4 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI = 13.8 – 36.6) and 37.7 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI = 29.5 – 48.0) for the trauma and elective hospital admissions, respectively

- The risk of being diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in the post-acute period following SARS-CoV-2 infection was significantly higher, compared to those in the unexposed trauma cohort (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.4, 95% CI = 1.58 – 3.64), unexposed elective cohort (HR = 2.9, 95% CI = 2.00 – 4.13), historic trauma cohort (HR = 4.2, 95% CI = 2.56 – 7.04) and historic elective cohort (HR = 2.4, 95% CI = 1.81 – 3.10)

- A stronger association was observed during the period when the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant was the predominant circulating variant (HR = 2.6, 95% CI = 1.24 – 5.65), however, this analysis was based on smaller case numbers and the hazard ratios have wide confidence intervals

- The authors concluded that exposure to SARS-CoV-2 was associated with a significantly increased risk of being diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, although the absolute risk of this was still low

- Further investigation needs to be conducted on the mechanisms underlying the association (i.e. whether there is something specific about how SARS-CoV-2 may unmask type 1 diabetes or whether other viruses act in the same way) and whether vaccination status affects results

- Study limitations include:

- Inaccuracies and coding mistakes in patient health records and misclassification in the National Diabetes Audit which may influence these results, e.g. type was not recorded in 9% of diabetes diagnoses, prescription or laboratory testing data was not available to confirm the accuracy of the diagnosis

- Variation in health-seeking behaviours during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Some people could have avoided testing or seeking medical attention and therefore were not captured or were recorded in the wrong cohort (e.g. some of the unexposed cohort did have SARS-CoV-2, but did not test).

Ward JL, Cruz J, Harwood R, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and new‐onset type 1 diabetes in the post‐acute period among children and young people in England. Diabet Med 2025. doi:10.1111/dme.70084.

This Bulletin is supported by the South Link Education Trust

This Bulletin is supported by the South Link Education Trust

If you have any information you would like us to add to our next bulletin, please email:

editor@bpac.org.nz

© This resource is the subject of copyright which is owned by bpacnz. You may access it, but you may not reproduce it or any part of it except in the limited situations described in the terms of use on our website.