Published: 30th May, 2025

The following questions can be used as discussion points for peer groups or self-reflection of practice.

It is strongly recommended that the following article is read before considering the questions:

This peer group discussion builds on the scope of the main gout article (above) and considers additional factors influencing the long-term success of gout treatment, e.g. potential barriers, framing conversations with patients, a “team approach” to care.

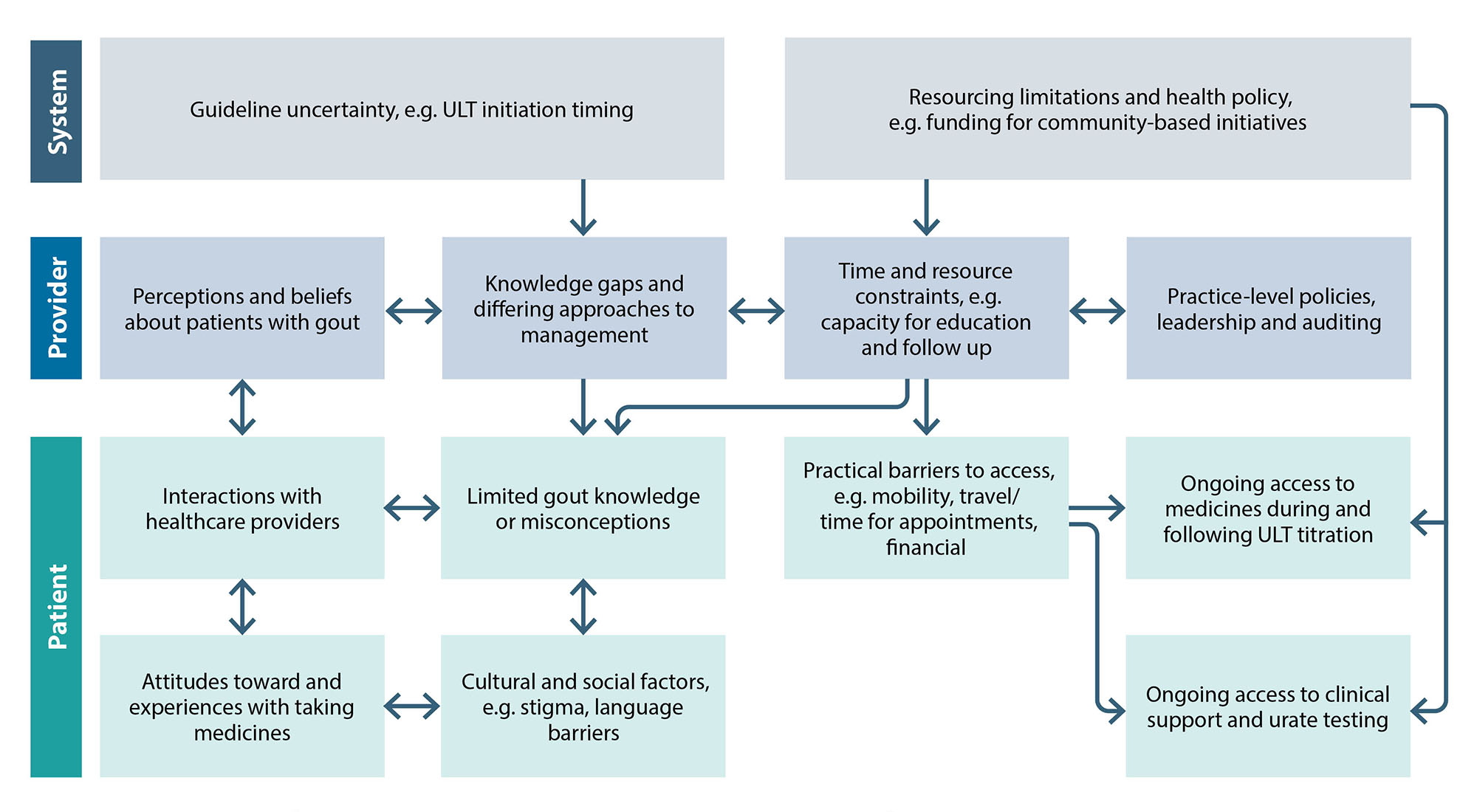

There are multiple intersecting barriers to the early and optimal use of urate-lowering medicines (Figure 1).1 Patient-, provider- and system-level factors all influence gout management, along with regional and practice-specific issues.1 Proactively identifying and addressing potential barriers can be the difference between successful or suboptimal care.

Most patients with gout are managed in the community, therefore it makes sense to focus solutions within this context. However, not all factors are within the direct control of primary care. For example, some patients have a reduced capacity to regularly attend appointments (e.g. those with impaired mobility or who live rurally) or struggle to afford consultation, prescription or transportation costs. Once a diagnosis has been made and patients have been initiated on urate-lowering treatment, scheduling telehealth/phone check-ins with the practice, point-of-care serum urate testing in the community or enacting standing orders to enable dose escalation by other health professionals (e.g. pharmacists) may help to address such barriers. Perceptions and beliefs about gout can also contribute to delays in initiating and maintaining effective urate-lowering treatment (see: “Deliver messages the patients and whānau need to hear”).1

Gout Guide as a tool to strengthen the approach to gout management in primary care. In 2023, the Gout Guide was launched, following a project funded by Te Whatu Ora Long-Term Conditions Directorate. The toolkit of resources includes clinician education modules, clinical pathways, case studies, patient/whānau leaflets/booklets, as well as key recommendations for improving gout care within general practices and alleviating barriers to care.

Gout Guide as a tool to strengthen the approach to gout management in primary care. In 2023, the Gout Guide was launched, following a project funded by Te Whatu Ora Long-Term Conditions Directorate. The toolkit of resources includes clinician education modules, clinical pathways, case studies, patient/whānau leaflets/booklets, as well as key recommendations for improving gout care within general practices and alleviating barriers to care.

For further information on Gout Guide and to access resources, see: goutguide.nz

Figure 1. Barriers to effective gout management in primary care. Adapted from Rai et al, 2018.1

A structured approach is recommended to overcome misconceptions that are barriers to care:2

- Ask – assess the patient’s understanding about gout

- Build – grow their knowledge by validating information that is correct, filling in knowledge gaps and correcting misconceptions

- Check – verify the patient has understood information that has been delivered

The goal is to form a loop of communication, with gaps in understanding forming the basis for further discussion. Further information on effective discussion and communication about gout management with patients is available from: bpac.org.nz/bpj/2014/april/gout.aspx (published in 2014; some information may no longer be current).

Deliver messages the patients and whānau need to hear 1, 2

Do not blame yourself because you have gout. Lifestyle factors can trigger gout flares but are not a major cause of the condition. Biological factors (e.g. genetic variants, chronic kidney disease) and some medicines (e.g. diuretics) contribute significantly to gout risk, and account for the higher prevalence among Māori and Pacific peoples. Explaining to patients that they may have a genetic predisposition to gout helps to dispel the perception that the condition is self-inflicted.

Gout is serious, it’s not just “a pain in the toe”. Patients should understand that beyond possible long-term musculoskeletal disability, gout is also associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular and renal complications. However, if they actively manage their condition, they can reduce this risk, e.g. by regularly taking preventative medicines and making appropriate lifestyle changes.

Just because it’s not hurting right now doesn’t mean that gout isn’t hurting you. Urate crystals are still present in the joint after a flare has settled. Even in the absence of clinically apparent symptoms, chronic inflammatory processes associated with the response to crystal deposition can still cause progressive damage to tissue throughout the body. The crystals will only dissolve if the serum urate level in the blood is kept low by regular use of medicines such as allopurinol (< 0.36 mmol/L in general, or < 0.30 mmol/L for patients with severe gout, e.g. tophi).

In the long term, allopurinol can stop flares from happening. If patients regularly use urate-lowering treatment and serum urate levels are treated to target, flares of gout can be eliminated for many people within two years.

Allopurinol is a safe and highly effective medicine. Urate-lowering medicines such as allopurinol are associated with an increased risk of flares in the first months of treatment and this may discourage some patients from taking them, even if they have collected the prescription from a pharmacy. Patients can be reassured that with prophylactic medicines and appropriate dose titration, the risk of allopurinol causing a flare will be substantially reduced and ongoing use will prevent future flares.

For patient gout resources, including Māori, Samoan and Tongan language versions, see: goutguide.nz

Gout Guide also includes useful discussion prompts to facilitate better conversations about gout, including when patients initially seem unengaged in managing their condition.

Gout Guide also includes useful discussion prompts to facilitate better conversations about gout, including when patients initially seem unengaged in managing their condition.

Rongoā rākau does not interfere with conventional gout treatments

Rongoā rākau (traditional plant remedies with healing properties) may be used by some patients to treat gout flares, e.g. a poultice applied to the affected joint or plant material added to bathwater.3 Urate-lowering medicines can be used safely with Rongoā rākau; this combination should not be discouraged. Positive discussions about traditional medicines are helpful as they break down barriers with patients and allow prescribers to assess if any interactions with conventional medicines are likely.

Most patients with gout can achieve serum urate targets if they are provided with effective support. However, the time available in standard 15-minute general practice appointments can make it challenging for clinicians to provide sufficient education following diagnosis and initial medicine prescribing. Where possible, other members of the practice team (e.g. nurses, pharmacists, health improvement practitioners, health coaches) can assist with reinforcement of the messages, and this may include:

- More detailed information about gout, e.g. definition, causes, associations, consequences

- A discussion about perceptions

- Emphasis on why monitoring/adherence to long-term medicines is important

Community pharmacists can also assist in reducing delays in diagnosis and the initiation of urate-lowering treatments by asking patients who are purchasing NSAIDs about their symptoms. Patients who may have gout (e.g. those with a history of gout-like flares), should be told there are other methods for stopping flares in the long-term (i.e. urate-lowering treatment), and encouraged to present to general practice for an assessment. Pharmacies can also offer more direct support as part of the multidisciplinary team in the long-term, including:

Point-of-care serum urate testing. For further information, see: goutguide.nz.

Point-of-care serum urate testing. For further information, see: goutguide.nz.

Allopurinol dose escalation under standing orders. For further information, see: goutguide.nz.

Allopurinol dose escalation under standing orders. For further information, see: goutguide.nz.

Inspiration can be drawn from New Zealand gout initiatives

There are multiple examples of successful community initiatives involving community pharmacists, practice nurses and general practitioners that have improved gout care in New Zealand. Gout programmes that started as pilot studies and subsequently expanded within their respective regions include:2

- Owning My Gout: a community pharmacist- and nurse-led model piloted in Counties Manukau. General practitioners issue standing orders for community pharmacists to titrate and dispense allopurinol in collaboration with practice nurses. Providers also collaboratively helped to build patient health literacy.

- Gout Stop programme: provided by Mahitahi Hauora PHO in Northland and based on a 91-day model of collaboration between general practitioners, community pharmacists and Kaiāwhina. These groups worked together to improve accessibility to medicines and health literacy, and included four-stage “Gout Stop pack” options for prescribers (based on renal function/diabetes status) pre-loaded into the PMS. This programme informed the subsequent Whanganui Gout Stop programme.

For further information on these programmes and other New Zealand gout initiatives, see: goutguide.nz

Contact your PHO to see what support is available in your area. Even if there is not dedicated gout services or funding available, lessons can be shared from previous initiatives to support positive changes in the approach to gout care.

References

- Rai SK, Choi HK, Choi SHJ, et al. Key barriers to gout care: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Rheumatology 2018;57:1282–92. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kex530

- Health Literacy NZ, Health Navigator Charitable Trust. The Gout Guide. 2023. Available from: https://goutguide.nz/ (Accessed May, 2025).

- Te Karu L, Bryant L, Elley CR. Maori experiences and perceptions of gout and its treatment: a kaupapa Maori qualitative study. J Prim Health Care 2013;5:214–22.

- What are some of the common misconceptions you have encountered regarding gout? Do you find there to be differences in perceptions/beliefs between different patient groups?

- What is your threshold for initiating urate-lowering treatment? Have you encountered resistance when recommending urate-lowering treatment? If so, what were the key concerns patients expressed, and what approaches helped to convince them that trialling it would be a good idea?

- Once urate-lowering treatment has been initiated, what have you found are the most common barriers to achieving long-term success in gout management? For patients with reduced access to regular appointments what strategies have you used or could use to improve engagement and adherence?

- What is your current approach to follow-up, treatment escalation and monitoring for patients initiated on urate-lowering treatment? Do you consistently ensure you “treat to target”?

- Are you aware of any gout initiatives available in your region? What additional services or resources would help you to improve the delivery of gout care?

- How could your primary care team (e.g. clinicians, nurses, pharmacists, health improvement practitioners) collaborate differently to support long-term gout management? Would implementing strategies such as standing orders (e.g. pharmacist-led dose escalation), point-of-care urate testing or consistently setting and actioning patient recalls help your approach? Are there other ways this process could be improved?