The role of testosterone in adult males

Testosterone in males is responsible for the development and maintenance of typical secondary sex characteristics, such

as increased facial and body hair, increased muscle growth, increased bone mass, and effects on libido.1 It

also has effects on energy and stamina, and psychological influences, e.g. on mood and drive.

In adult males, approximately 95% of testosterone is produced in the testes, with the remainder produced by the adrenal

gland.1 The effects of testosterone in the body can derive from testosterone itself, from conversion to its

active metabolite dihydrotestosterone (DHT) and conversion to oestrogen by aromatase enzymes.2

Production of testosterone is regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal reproductive axis (HPG axis). The hypothalamus

secretes gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which in turn causes the anterior pituitary to release luteinising hormone

(LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH). LH stimulates Leydig cells in the testes to produce testosterone. Most of

the testosterone in the body (total testosterone) is bound to sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) or weakly bound to albumin;

approximately 1 – 3% of total testosterone is non-bound (free testosterone).3 While free testosterone is

the fraction available for uptake and binding to androgen receptors in the tissues, measurement of free testosterone (by

measuring SHBG) is not usually necessary. Total testosterone measurement is the key laboratory test for assessing gonadal

function in males.

Hypogonadism can have an early or late onset, and can result from a low or absent testicular production of testosterone

despite increased stimulation from the pituitary (primary hypogonadism), a failure of the appropriate output from the

hypothalamus and pituitary (secondary hypogonadism) or a combination of the two.

Testosterone levels generally decline with age

Unlike the relatively abrupt fall in oestrogen levels in women during menopause, in most population studies testosterone

production declines very slowly with age in males. The diurnal rhythm of peak levels in the morning and lowest levels

in the afternoon and evening also becomes less pronounced.3 In addition, the concentration of SHBG increases

in males with age, therefore resulting in declining levels of free testosterone.3 In cohorts of males aged

40 years and older, total testosterone levels have been observed to fall by 1 – 2% per year.4 However, the

rate of decline varies between individuals and is influenced by factors such as obesity, co-morbid conditions and some

medicines. Changes in reproductive hormone levels with age are not inevitable or universal and some studies of healthy

active older males suggest they retain reproductive hormone levels comparable with younger males.5 Age-related

testosterone decline results from dysfunction in both testicular and hypothalamic-pituitary function, and therefore can

have aspects of both primary and secondary hypogonadism.5

Are we “disease mongering”?

There has been considerable concern in the international literature that the clinical significance of testosterone decline

in ageing males has been overstated (largely by pharmaceutical companies who manufacture testosterone products), and that

testosterone supplementation in males with low levels due to ageing is not justified based on current evidence.6–8 An

increase in prescriptions for testosterone has been observed in many countries over the past decade, in the absence of

any research findings or changes in clinical guidance to prompt a change in prescribing. For example, in the United States

the number of patients prescribed testosterone increased by 76% between 2010 (1,299,846) and 2013 (2,291,266), with approximately

0.7% of the population being prescribed testosterone.7, 9 Furthermore, a sample of 250,000 males prescribed

testosterone found that only 72% had evidence of undergoing a testosterone measurement prior to initiating use, so that

approximately one-quarter of patients had apparently not been diagnosed using a standard appropriate to best clinical

care.7 Similar trends of increasing testosterone use have been observed in the United Kingdom and Australia.6, 8

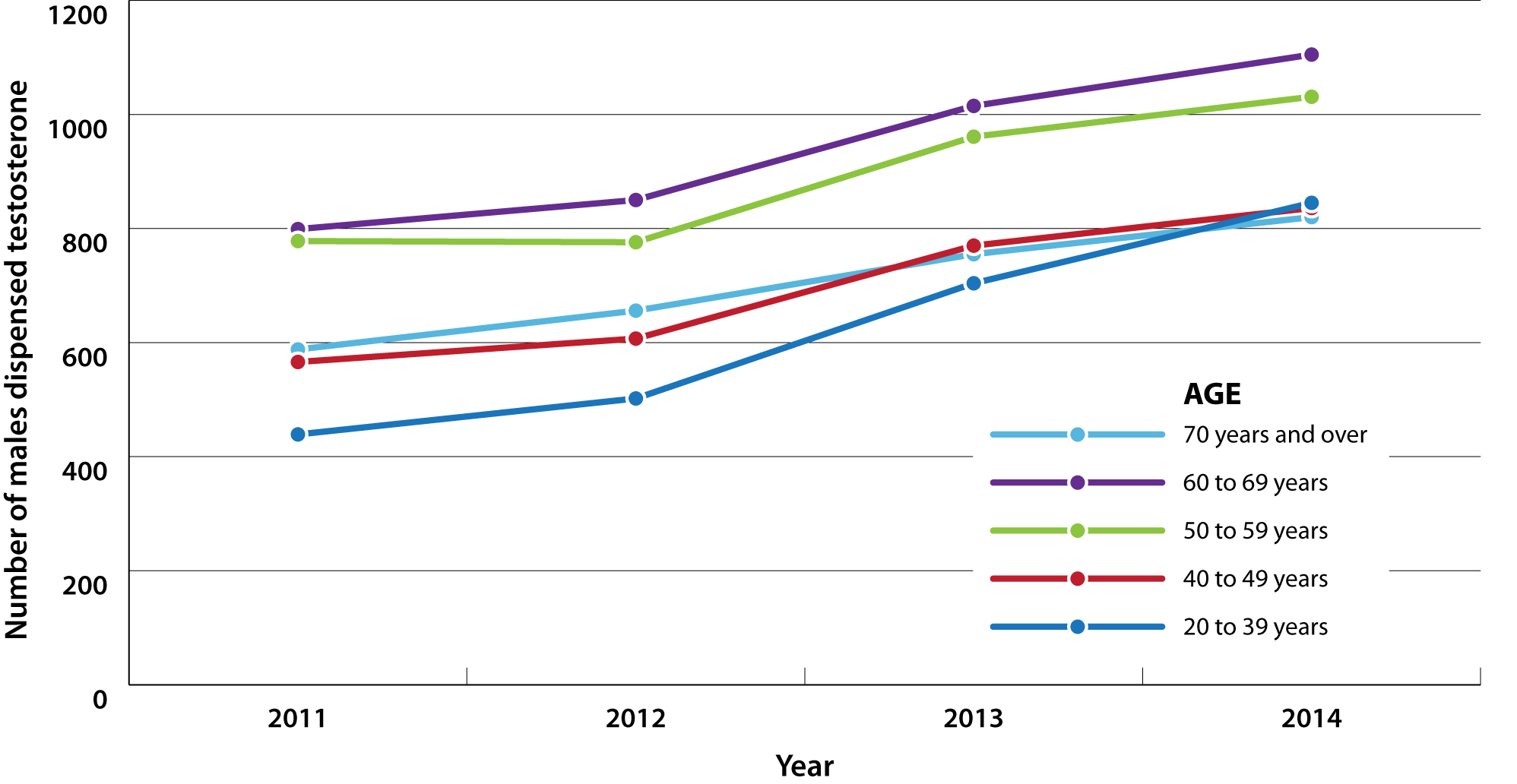

Testosterone dispensing in New Zealand

Testosterone use in New Zealand is lower overall than in the United States, with approximately 0.2% of the male population

being dispensed testosterone in 2013.10, 11 However, data from New Zealand indicate that use has increased

over the last few years, from 3,129 males dispensed testosterone preparations in 2011 to 4,415 in 2014; a 41% increase.11 While

the largest group of males dispensed testosterone are those aged 50 years and older, increases in dispensing rates during

this time have occurred across all age groups (Figure 1). This increase in the number of people using testosterone could

be due to population rise, an increasing clinical recognition and detection of hypogonadism, inappropriate prescribing

or any combination of these factors; dispensing data do not allow an assessment of the underlying reasons for prescription.

However, given the international experience, it is worthwhile considering the clinical indications and current guidelines

for prescribing testosterone.

Figure 1: Number of males dispensed testosterone (all formulations) by age group in New Zealand from 2011 to 2014.

So, is testosterone an appropriate treatment for ageing males?

In March 2015, the United States Food and Drug Administration cautioned against the use of testosterone treatment in

older males with low testosterone levels for no apparent reason other than ageing.12 There is a lack of randomised

controlled trials assessing benefits and risks of testosterone supplementation to guide evidence-based management of older

males who experience symptoms of hypogonadism and have low levels of testosterone. Therefore, testosterone treatment in

older males should only be considered in those with clinically established hypogonadism, with symptoms and signs that

significantly impact their quality of life, after reversible causes have been eliminated, other treatments had been trialled,

and discussion about the lack of conclusive evidence of both benefit and adverse effects.

For further discussion of the evidence on cardiovascular safety of testosterone, see: “Recent

research into testosterone use in older males spells a note of caution” below.

For further discussion of the evidence on cardiovascular safety of testosterone, see: “Recent

research into testosterone use in older males spells a note of caution” below.

Recent research into testosterone use in older males spells a note of caution

Three recent studies investigating the use of testosterone in older males have generated media coverage and controversy

in medical journals regarding whether testosterone use increases cardiovascular risk in these men.13–15 These

recent studies have recognised weaknesses in study design and it would be inappropriate to base treatment decisions on

these studies alone, but their results do raise concern.

Reaction from regulatory and clinical bodies

Organisations and committees such as the United States’ Food and Drug Administration (FDA), American Urological Association

and New Zealand’s Medicines Adverse Reaction Committee have all met to discuss these findings. Their conclusions are not

entirely congruent, which reflects the varying interpretations possible from the current evidence and highlights the current

uncertainty surrounding the risks and benefits of prescribing testosterone in older males:

- The FDA recommended on the basis of these studies that information labels for testosterone products include that there

may be an increased risk of cardiovascular disease12

- The New Zealand Medicines Adverse Reactions Committee concluded that there was no statistical evidence to support an

association between testosterone replacement (as opposed to misuse) and myocardial infarction, venous thromboembolism

or stroke16

- The American Urological Association concluded that evidence was contradictory and that definitive studies had not been

performed17

Lessons from the Women’s Health Initiative: randomised controlled trials are necessary to evaluate risks and benefits

The reality of medical practice is that medicines are prescribed on the basis of the safety information at hand, and

with further time and research additional adverse effects can come to light which alter the balance of risks and benefits

for any medicine. The current situation of testosterone use in older males is clearly reminiscent of the practice of prescribing

reproductive hormones to peri- and postmenopausal females to alleviate the symptoms of menopause. In that case, the Women’s

Health Initiative study produced a sudden change in medical practice as the risks of hormone treatment from randomised

controlled trial data were greatly different from previous data available from case control studies. There is obvious

concern that a similar situation could arise for the prescription of testosterone in older males, where this practice

could become widespread only to be later shown in appropriately controlled trials to carry substantial risks.

The bottom line – for now

At present, there are concerns that testosterone use could cause adverse cardiovascular effects in older males but there

is also a clear acknowledgement that additional randomised controlled trials specifically designed to provide safety information

in this patient group are necessary.

Assessing older males with potentially low testosterone levels

- Patient history: does the patient report specific symptoms of hypogonadism, or could non-specific symptoms be explained

by other causes, including expected age-related changes?

- Clinical examination: are there any features that support a diagnosis of hypogonadism or suggest a possible cause?

- Investigation: does the patient have specific features of hypogonadism present, that are impacting the quality

of their life, and therefore investigation of testosterone levels is warranted?

Symptoms, signs and risk factors for hypogonadism

Many of the symptoms and signs of hypogonadism are non-specific, present in other conditions and are also associated

with ageing, making diagnosis challenging. In addition, patients may experience symptoms of hypogonadism at variable testosterone

levels.2 Therefore a diagnosis of hypogonadism is more certain in patients with multiple, more specific features

consistent with low testosterone, rather than isolated symptoms.5

Symptoms and signs of hypogonadism are given in Table 1; these features are not individually diagnostic of hypogonadism.

A study of over 3,000 males aged 40 to 79 years found that a combination of three sexual symptoms was highly predictive

of low testosterone levels and the presence of these three features might suggest that investigation of testosterone levels

is warranted: 18

- Decreased frequency of morning erections

- Erectile dysfunction (inability to achieve or maintain penile erection for satisfactory sexual performance)

- Decreased frequency of sexual thoughts (low sexual desire)

Table 1: Symptoms and signs of testosterone deficiency in males (features are not individually

diagnostic of hypogonadism)5

| More specific |

|

- Decreased or absent early morning/spontaneous erection

- Reduced libido and sexual activity (often an early symptom of deficiency)

- Erectile dysfunction

- Breast discomfort, gynaecomastia (more common with primary hypogonadism)

- Loss of facial, axillary and pubic hair (usually only if long-term deficiency)

|

- Testicular atrophy

- Infertility, low sperm count (usually only if long-term deficiency)

- Height loss, low velocity fractures, low bone mineral density

- Hot flushes, sweats (usually only if severe deficiency or rapid decrease)

|

| Less specific |

|

- Decreased energy, motivation and confidence

- Depressed mood (often an early symptom of deficiency)

- Poor concentration and memory

- Sleep disturbance and increased sleepiness

|

- Mild anaemia (normochromic)

- Reduced muscle bulk and strength (usually only if long-term deficiency)

- Increased body mass index and body fat

- Decreased physical performance

|

A number of medical conditions can influence the function of the HPG axis and are associated with hypogonadism.

Patients with these conditions do not necessarily need to be investigated for hypogonadism, but the presence of the co-morbidity,

along with symptoms and signs of testosterone deficiency, would increase suspicion of the diagnosis. Conditions associated

with hypogonadism include:2, 3, 19

- End-stage renal disease

- Osteoporosis

- Moderate to severe COPD

- Severe obstructive sleep apnoea

- Type 2 diabetes (see note below)

- Pituitary tumour

- HIV

- Testicular cancer

- Haemochromatosis

- Chronic inflammatory disease, e.g. arthritis

- Eating disorders (malnutrition)

N.B. Testosterone levels are approximately 3 nmol/L lower in males with type 2 diabetes. However, these patients should

only be prescribed testosterone if they meet diagnostic requirements for hypogonadism. Evidence does not support the use

of testosterone to improve diabetes control.20

The use of some medicines is also associated with hypogonadism, including:2, 3, 19

- Opioids

- High dose systemic corticosteroids

- Anabolic steroids

- Oestrogens and progesterones

- Chemotherapy medicines

- GnRH antagonist, e.g. prostate cancer treatment

- Phenothiazines

Lifestyle factors associated with hypogonadism include:19

- Obesity

- Chronic excess alcohol intake (recent alcohol intake can also cause transient decreases in total testosterone levels)

- Vigorous exercise

- Significant stress

- Sleep deprivation

- Illicit drug use, including misuse of anabolic steroids

Clinical examination should focus on assessing the patient’s body hair distribution and testicular size,

and assessing for gynaecomastia. If pituitary disease is suspected, evidence of deficiency of other endocrine axes (e.g.

secondary hypothyroidism, hypoadrenalism) and assessment of visual fields should be considered.

Investigate testosterone levels if significant features of hypogonadism are present

The diagnosis of hypogonadism in males should be based on the presence of consistent symptoms and signs of hypogonadism

in combination with a finding of a low testosterone level.5 Therefore, measuring testosterone is not necessary

unless patients show symptoms and signs related to altered function of the HPG axis. When considering the timing of testing,

control for factors that may cause a transitory drop in testosterone levels such as acute illness, recent alcohol intake

or excessive exercise.19

Investigation of testosterone levels should be carried out before the patient begins any testosterone replacement treatment.

Evaluation of the HPG axis becomes very difficult in patients who are already taking, or have been recently taking, testosterone

replacement in any form, as endogenous testosterone production can be suppressed. These influences can persist for weeks

or even months after stopping such preparations.

The recommended initial laboratory investigation for hypogonadism is an early morning serum total testosterone when

the patient is well. The suggested protocol is as follows:19

- Request a total testosterone test between 7 am – 10 am (unless the patient is a long-term shift worker; shift workers

who sleep during the day have highest levels in the afternoon)

- If the level is within the reference range, no further testing is required

- If the level is below the reference range, repeat the test at least once to confirm a consistently low result;

30% of males with an initial low testosterone level will have a normal level on re-testing

- Request a LH test with the subsequent testosterone test to help distinguish between primary and secondary hypogonadism

- Consider testing SHBG and free testosterone only if there is reason to suspect that SHBG levels may be abnormal

(e.g. marked obesity, thyroid disease, treatment with some medicines such as anticonvulsants); some males

with total testosterone levels in the lower normal range may exhibit hypogonadism due to elevated SHBG levels

and low free testosterone

Reference intervals for testosterone differ depending on the assay used; consult your local laboratory. A general reference

interval for total testosterone in adult males is 11–40 nmol/L.19 The testosterone level at which signs and

symptoms of deficiency become apparent varies between individuals and the likelihood of symptoms increases at testosterone

levels near the lower limit of the reference range for healthy young males.2, 5 However, it is generally

agreed that if the level is consistently below 8 nmol/L, this is diagnostic of hypogonadism, in conjunction with relevant

symptoms and signs.2, 18

It is recommended that patients with consistently low testosterone levels are discussed with an endocrinologist to guide

further investigations. Primary hypogonadism is characterised by low testosterone levels along with elevated LH levels.

If seminiferous tubule function and spermatogenesis is also affected, then FSH may also be elevated. Secondary hypogonadism

is most commonly associated with low LH or inappropriately normal levels of LH in a patient with low testosterone levels.3 A

prolactin test may be indicated if a pituitary tumour is suspected as a cause of secondary hypogonadism.19

Erectile dysfunction is a common reason for men to request testosterone investigation

A common reason for an older male to ask their general practitioner to investigate their testosterone level is because

they are experiencing a sexual problem such as erectile dysfunction.

If erectile dysfunction is their only symptom of hypogonadism, investigation of testosterone levels is not warranted;

erectile dysfunction is only rarely caused by low testosterone levels and is more likely to be caused by neurological

or vascular disease, medicines or psychological factors. A PDE-5 inhibitor such as sildenafil is first-line treatment,

after modifiable causes have been addressed.

If the patient has erectile dysfunction, along with other symptoms of hypogonadism, such as decreased frequency of morning

erections and low libido (sexual thoughts), it is reasonable to request a serum total testosterone level. If

the level is below the reference range, the test should be repeated to confirm consistently low testosterone

levels.

If a testosterone deficiency is established, testosterone replacement treatment can be discussed as an option to improve

some sexual dysfunction symptoms. Improvements in libido and sexual function in general have been reported in

males taking testosterone replacement. However, testosterone treatment is not thought to significantly improve

erectile dysfunction when compared to the use of sildenafil.

For further information, see: “Selected topics in men’s health: erectile

dysfunction”, Best Tests (Sep, 2010).

For further information, see: “Selected topics in men’s health: erectile

dysfunction”, Best Tests (Sep, 2010).

Managing older males with established testosterone deficiency

- Manage modifiable factors: does the patient have co-morbidities (including the effect of medicines) or lifestyle

factors that can be optimally managed to improve symptoms?

- Consider testosterone treatment as an option: Does the patient have specific features for which improvement with

testosterone treatment can be measured/assessed? Does the patient have any contraindications or risk factors

for treatment? Have you explained the risks and benefits of testosterone treatment and monitoring requirements

to the patient?

- Second opinion: have you discussed the management strategy and possible treatment options with an endocrinologist?

- Monitoring testosterone treatment if prescribed: has testosterone treatment resulted in an improvement of symptoms?

Are there any adverse effects of treatment?

Address reversible causes of hypogonadism

If a patient is confirmed to have hypogonadism, any co-morbidities or lifestyle factors that may be contributing to

their symptoms and signs should be optimally managed before considering testosterone replacement treatment. This may involve

recommending increased physical activity, weight loss and smoking cessation and reviewing treatment for COPD, sleep disorders

(e.g. obstructive sleep apnoea), diabetes or any other long-term conditions.

Discuss the pros and cons of testosterone treatment

Testosterone replacement is a treatment option for older males with established hypogonadism; it is more likely to be

worthwhile for those with specific symptoms for which improvements can be evaluated. The decision whether to initiate

testosterone should take place after a discussion with the patient on the benefits and risks of treatment, which to some

extent are both uncertain as detailed data on long-term health benefits and risks in large randomised controlled trials

is currently lacking.5 In addition, patients should be made aware of the testing requirements both prior

to initiating treatment (e.g. for the possibility of undetected prostate cancer), and during treatment to assess response

and safety (e.g. haematocrit levels).

The benefits of testosterone treatment can include a reduction in depressive symptoms and improvements

in mood and cognitive functioning, an overall feeling of energy and well-being and reported improvements in libido and

sexual function.2, 5 For males with erectile dysfunction and low testosterone levels, however, a large randomised

controlled trial investigating the effect of testosterone replacement in addition to sildenafil found that the combination

of treatment was not superior to sildenafil plus placebo in improving erectile function.21 Effects which

can be ascertained by the clinician include changes in body composition, such as an increase in muscle mass and a decrease

in abdominal fat, and changes in surrogate markers of cardiovascular risk; testosterone treatment may improve a patient’s

glycaemic control and lipid profile, depending on their initial state of health.2

Potential adverse effects of testosterone treatment

Secondary polycythaemia is one of the main adverse effects of testosterone treatment, detected by an elevation in haematocrit

levels (also referred to as packed cell volume – PCV). It is caused when levels of testosterone rise above the normal

physiological range, and is more likely to occur with injectable preparations where the treatment regimen causes fluctuating

testosterone levels.5 Polycythaemia can lead to cardiovascular and thrombotic complications due to the increased

viscosity of the blood and thrombosis. In men already at relatively high cardiovascular risk, testosterone treatment has

been associated with an increase in cardiovascular events, and should be used with caution.22

For further discussion of the evidence on cardiovascular

safety of testosterone, see: “Recent

research into testosterone use in older males spells a note of caution”.

For further discussion of the evidence on cardiovascular

safety of testosterone, see: “Recent

research into testosterone use in older males spells a note of caution”.

Growth of a prostate cancer may be accelerated with testosterone treatment. Meta-analyses have not shown

that testosterone treatment causes the initiation of prostate cancer, but rather may increase the rate of growth of pre-existing

androgen-dependent prostate cancer cells.2

Sperm production reduces with testosterone supplementation. Therefore it is not an appropriate treatment

for men who wish to retain their fertility. Depending on the underlying cause, suppressed spermatogenesis due to testosterone

treatment can potentially be reinitiated by hCG treatment under specialist fertility clinic care.

Other adverse effects experienced by males taking testosterone include acne, oily skin and worsening of

male pattern baldness. There is weak evidence that testosterone treatment may induce or worsen obstructive sleep apnoea.5 Oral

formulations of testosterone have been rarely associated with hyperbilirubinaemia and liver toxicity.5

Testosterone treatment is contraindicated in males with:5, 23

- Metastatic prostate cancer

- Breast cancer

- Primary liver tumours

- Hypercalcaemia

- Nephrotic syndrome

Testosterone treatment is not recommended in males with:5

- A palpable prostate nodule or induration

- PSA > 4.0 ng/mL or 3.0 ng/mL if they have a family history of prostate cancer

- Severe lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia

- Haematocrit (PCV) > 50%

- Severe untreated obstructive sleep apnoea

- Uncontrolled or poorly controlled congestive heart failure

- Requirement for fertility

- Previous testosterone misuse

Initiating and monitoring testosterone treatment

If the decision is made that testosterone treatment is appropriate and the patient wishes to proceed, it is recommended

that this is discussed with an endocrinologist. In most cases, an initial trial of testosterone treatment is recommended

for three to six months, to evaluate improvement in symptoms and tolerability. If symptoms do not improve within six months,

treatment should be discontinued.24 If testosterone treatment is found to be beneficial and therefore continued,

it is likely to be required long-term.

Prior to commencing treatment:

- Measure PSA in males aged 40 years or over; patients with PSA > 0.6 ng/mL should undergo a prostate examination5

- Measure haemoglobin and haematocrit levels (full blood count)

Selecting a preparation:

Fully subsidised testosterone treatment is available in New Zealand in oral, injectable and transdermal preparations

(Table 2). Most of these require an initial diagnosis and prescription from a specialist. General practitioners, however,

may be involved in the follow-up care and monitoring of these patients and subsequent prescription repeats. The choice

of testosterone formulation is largely based on patient preference.5 There is some evidence from a study

of patients taking testosterone in the United States and United Kingdom that short-acting injections carry a higher risk

of adverse cardiovascular effects than daily applications such as transdermal patches or gels (available overseas); this

study did not include patients using three-monthly testosterone undecanoate injections, which is an alternative injection

preparation available in New Zealand.25 The use of preparations taken on a daily basis (e.g. oral tablets

or patches) may be preferable during initial use to allow for withdrawal if adverse effects develop.2

Therapeutic range:

The aim of testosterone supplementation in males should be to provide circulating levels within the normal range for

their age group. In younger males, aim for a level within the mid-range of the reference interval, and in older males,

aim for the lower range of the interval.5 Testosterone levels should be assessed within three to six months

of initiating treatment and then at least annually thereafter.2, 5

The ideal time for monitoring testosterone levels depends on the preparation being used:5

- Injectable formulations: measure testosterone levels midway between the planned injection interval

- Oral undecanoate capsules: measure levels within three to five hours of dosing

- Transdermal patches: measure levels in the morning if the patch has been applied the previous evening

Monitoring for adverse effects:

PSA should be measured, and digital rectal examination performed, at three, six and 12 months after initiating treatment,

then according to local screening guidelines for all males.2, 5 Due to the effects of testosterone on the

prostate small increases in PSA are likely: a systematic review of testosterone supplementation in hypogonadal males found

an average PSA increase of 0.3 ng/mL in younger males and 0.44 ng/mL in older males, but large increases were rare.5 Discuss

with a urologist if PSA increases by > 1.4 ng/mL within 12 months, if PSA velocity is > 0.4 ng/mL/year (if testosterone

is taken for more than two years), if prostatic symptoms develop or if a prostatic abnormality is detected.5, 24

A full blood count should be requested at three, six and 12 months after initiating treatment, then annually thereafter.2,

5 If haematocrit rises above 54%, or 48% in patients with a history of thrombosis, stop testosterone treatment

until haematocrit levels return to normal. Testosterone may then be reinitiated at a lower dose or in a different formulation.5 Manifestations

of polycythaemia include digital ischaemia, neurological symptoms, hypertension, hypoxaemia and cor pulmonale.

There is no specific requirement to monitor cardiovascular health, however, most older males will already be receiving

regular cardiovascular risk assessment.

Discontinue treatment if intolerable or serious adverse effects occur or if no benefit is derived within

six months.24

Table 2: Testosterone formulations subsidised in New Zealand2, 23

|

Amount of active ingredient* |

Initial dosing interval* |

Notes |

| Intramuscular injections: |

Testosterone esters† |

250 mg in 1 mL injection |

250 mg, every three weeks |

Fluctuations in testosterone levels occur across injection cycle with higher levels following injections,

tapering off over time. Patients may experience fluctuations in symptoms of hypogonadism.

Risk of elevated haematocrit is greater with injections due to periods of elevation of testosterone above physiological

range.

To be given by deep IM injection, e.g. gluteal muscle |

Depo-testosterone (testosterone cipionate)† |

1000 mg in 10 mL injection |

50 – 400 mg, every two to four weeks |

Testosterone undecanoate (undecylate)† |

1000 mg in 4 mL injection |

1000 mg, every 10 – 14 weeks |

| Oral capsules: |

Testosterone undecanoate (undecylate)† |

40 mg |

120–160 mg, daily, in two divided doses initially, reduced to 40 – 120 mg, daily, in two divided doses |

Recommended to be taken with or immediately after food. Absorption is dependent on fat intake, adequate absorption

is, however, usually achieved as long as patients are not fasting or taking with low-fat meals.26 |

| Transdermal applications: |

Transdermal patch |

2.5 mg delivered over 24 hours, recommended to be applied at 10 pm daily to mimic normal circadian rhythm |

2.5 – 7.5 mg, daily |

Frequently causes skin reactions – including blistering and burning. More than one patch will be required, and

applied at the same time, for doses above 2.5 mg daily.

To be applied to intact, non-scrotal skin (e.g. back, abdomen, thighs, upper arms) and pressed firmly in place, especially

around the edges; the area of application should be changed to give an interval of seven days between applications

to the same site |

* Due to differences in testosterone salts used in injections and bioavailability, the amount of testosterone administered is not directly

comparable across formulations. Dosing amount and interval should be adjusted according to response to achieve a physiological testosterone level.

† These formulations are “retail pharmacy – Specialist” which means that specialist prescription or endorsement is required for subsidy;

all listed formulations are fully subsidised.