Published: June, 2024 | Review date: June, 2027

The purpose of this audit is to assess anticholinergic burden in

older patients who are prescribed anticholinergic medicines

and determine if their current treatment is still appropriate.

Anticholinergic medicines are indicated for range of medical

conditions and include antidepressants, antihistamines,

antipsychotics and medicines to treat urinary urgency and

incontinence (Table 1). People who are prescribed multiple

medicines with anticholinergic activity are at increased risk

of adverse effects (e.g. dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary

retention and drowsiness) and this cumulative anticholinergic

influence is referred to as the anticholinergic burden,

although it can occur with just one anticholinergic medicine.

In New Zealand, more than 40% of people aged over 65 years

are exposed to medicines with anticholinergic activity.1

This

group is more likely to experience anticholinergic burden

due to age-related changes in physiology, and increased

likelihood of multiple morbidities requiring management

with anticholinergic medicines. To prevent unnecessary

exposure to associated risks, anticholinergic medicines

should only be prescribed to people with a specific clinical

indication for treatment, and at the lowest effective dose for

the shortest period of time.

Given the range of medical conditions that anticholinergic

medicines are prescribed to manage, each clinician is likely

to have a number of patients who are being treated with

these medicines; some for longer than is recommended or

with a higher dose than is necessary. These patients may

benefit from a dose reduction or deprescribing, depending

on the clinical scenario and the patient’s therapeutic goals

and treatment preferences. Patients who still require

pharmacological management may benefit from switching

to medicines with lower or no anticholinergic activity, if

available. Non-pharmacological interventions should also be

prioritised to reduce the required dose of, or overall need for,

anticholinergic medicines.

When deprescribing or switching medicines, gradual dose

tapering of the original anticholinergic medicine may be

required to limit withdrawal symptoms. A general “rule of

thumb” for tapering anticholinergic medicines is to reduce

the prescribed dose by 25 – 50% over a period of one to four

weeks. Close monitoring is required over the tapering period

for anticholinergic withdrawal symptoms (over the first one

to three days) and recurrence of symptoms associated with

the condition originally being treated (after approximately

seven days). Patients who develop withdrawal symptoms or

a reoccurrence of their original symptoms should restart the

medicine at the lowest tolerated dose and reattempt a slower

tapered reduction after 6 – 12 weeks. Alternate day dosing

may be beneficial in situations where available medicine

strengths are not appropriate for tapering. Clinicians should

ensure that any anticholinergic medicines prescribed for

short-term symptom management are not inadvertently

continued, e.g. orphenadrine for muscle spasms associated

with a lower back strain, promethazine for nausea and

vomiting or motion sickness.

There will be some patients taking anticholinergic medicines

long-term for whom reducing the dose or stopping the

anticholinergic medicine is not appropriate, e.g. clozapine

for schizophrenia. If required, medicines with anticholinergic

activity should be prescribed at the lowest effective dose, for

the shortest possible duration.

For further information on anticholinergic burden in

older people, see: bpac.org.nz/2024/anticholinergic.aspx

- Nishtala PS, Narayan SW, Wang T, et al. Associations of drug

burden index with falls, general practitioner visits, and mortality

in older people. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug 2014;23:753–8. doi:10.1002/pds.3624.

Table 1. Examples of prescription and over-the-counter medicines with anticholinergic activity.

N.B. This list is not exhaustive and

should be used a general guide only as there is inconsistency in anticholinergic rankings between sources. Any medicine with any level of anticholinergic

activity should be used with caution in patients susceptible to the adverse effects, especially if used in combination.

| Class |

Medicines with anticholinergic activity |

| High anticholinergic activity |

Mixed evidence for high anticholinergic activity* |

Moderate to low anticholinergic activity |

Antidepressants

SSRIs and SNRIs |

|

Paroxetine |

Citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine |

TCAs and other |

Amitriptyline, clomipramine, imipramine |

Nortriptyline |

Dosulepin, mirtazapine, moclobemide |

Antiepileptics |

|

|

Carbamazepine |

Antihistamine |

Chlorphenamine, dexchlorpheniramine, diphenhydramine, doxylamine, promethazine |

|

Cetirizine, fexofenadine, loratadine |

Antinausea |

Meclozine (meclizine) |

|

Cyclizine, prochlorperazine |

Antipsychotics |

Chlorpromazine, levomepromazine |

Clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine |

Amisulpride, aripiprazole, haloperidol, lithium, risperidone, ziprasidone |

Benzodiazepines |

|

Alprazolam |

Clobazam, clonazepam, diazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam, temazepam |

Bronchodilators (antimuscarinic) |

Ipratropium |

|

Glycopyrronium, tiotropium, umeclidinium |

Cardiac medicines |

Atropine |

Digoxin |

|

Diuretics |

|

Furosemide |

|

Gabapentinoids |

|

|

Gabapentin, pregabalin |

Gastrointestinal medicines |

Hyoscine (scopolamine) |

|

Domperidone, loperamide, metoclopramide |

Skeletal muscle relaxants |

Orphenadrine |

|

|

Opioids |

|

|

Codeine, dihydrocodeine, fentanyl, methadone, morphine, oxycodone, pethidine, tramadol |

Parkinson’s medicines |

Benzatropine, procyclidine |

|

Amantadine, levodopa |

Urinary urgency and incontinence medicines |

Oxybutynin†, solifenacin |

|

|

SNRI = serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA = tricyclic antidepressant

*High anticholinergic activity according to some, but not all anticholinergic rating scales

†The majority of evidence suggests oxybutynin has high anticholinergic activity

Summary

This audit identifies patients aged 65 years and over who are

currently taking an anticholinergic medicine to assess their

anticholinergic burden, whether the indication for treatment

remains and if reducing the dose (or stopping or switching

the medicine) is appropriate.

Recommended audit standards

Ideally, all patients who have been taking an anticholinergic

medicine for longer than six months* should have undergone

an assessment of their anticholinergic burden and have

documented evidence in their patient record of an indication

for ongoing treatment or evidence of a discussion about

stepping down to a lower dose or stopping completely. This

audit identifies patients who are prescribed an anticholinergic

medicine and should have their anticholinergic burden

assessed.

*The recommended duration of treatment for anticholinergic medicines

varies depending on the condition being managed. Six months has

been selected pragmatically for this audit to allow sufficient time for

patients who are prescribed anticholinergic medicines, e.g. oxybutynin

and solifenacin to treat urinary urgency and incontinence, to have

experienced an improvement in symptoms.

Eligible patients

All patients aged 65 years or over who are prescribed at least

one anticholinergic medicine are eligible for this audit.

Identifying patients

This is a “working audit” where the data sheet is filled in over

time when you have a consultation for any reason with an

eligible patient until the required number of patients has

been reached.

This is a “working audit” where the data sheet is filled in over

time when you have a consultation for any reason with an

eligible patient until the required number of patients has

been reached.

Sample size

The number of eligible patients will vary according to your

practice demographic. For the purposes of this audit, continue

until at least ten eligible patients have been identified and

included.

Criteria for a positive outcome

Anticholinergic burden should be assessed in a patient who

is prescribed an anticholinergic medicine for longer than

six months. If there is no record of a recent anticholinergic

medicine assessment in the patient’s clinical notes, this

should be undertaken at the time or planned for their

next appointment – the audit entry for the patient should

remain open until this is completed. The assessment

should include evaluation of all anticholinergic medicines

currently prescribed to the patient, any over-the-counter

use of anticholinergic medicines, and any adverse effects

they are experiencing that could be related to their use of

anticholinergic medicines (e.g. falls).

Based on the results of the assessment, a decision should

be made to continue prescribing the anticholinergic

medicine because the patient has an ongoing indication

and is benefiting from treatment, or that the patient would

benefit more from reducing or stopping (or switching)

the anticholinergic medicine because symptom relief is

insufficient, or they are experiencing adverse effects.

Following the assessment, a positive result is achieved if the

patient’s clinical notes contain:

- Documented evidence of assessment of anticholinergic

burden in the last six months (either undertaken

previously or as part of this audit); AND EITHER

- A record of a current indication for ongoing treatment

with an anticholinergic medicine, e.g. diagnosis of

urinary frequency, urgency or urge incontinence and

symptom improvement when taking the anticholinergic

medicine OR

- A record of a discussion with the patient about reducing

the dose or stopping the anticholinergic medicine

completely, or switching to an alternative medicine with

lower anticholinergic activity (if available)

Data analysis

Use the sheet provided to record your data. Aim to carry out

an assessment of anticholinergic burden for as many eligible

patients as possible.

Clinical audits can be an important tool to identify where gaps exist between expected and actual performance. Once completed, they can provide ideas on how to change practice and improve patient outcomes. General practitioners are encouraged to discuss the suitability and relevance of their proposed audit with their practice or peer group prior to commencement to ensure the relevance of the audit. Outcomes of the audit should also be discussed with the practice or peer group; this may be recorded as a learning activity reflection if suitable.

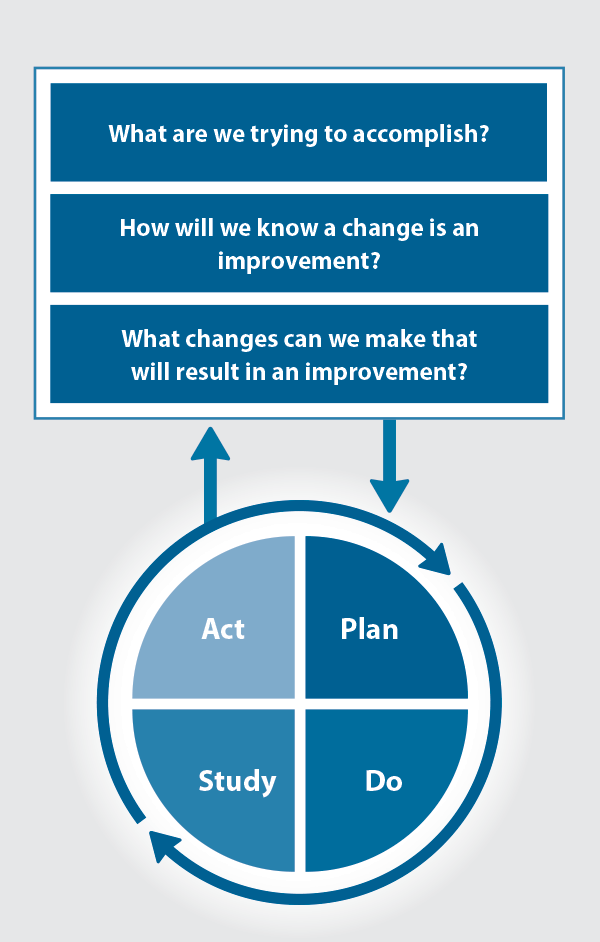

The Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) model is recommended by the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners (RNZCGP) as a framework for assessing whether a clinical audit is relevant to your practice. This model has been widely used in healthcare settings since 2000. It consists of two parts, the framework and the PDSA cycle itself, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The PDSA model for improvement.

Source: Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycles and the model for improvement

1. The framework

This consists of three questions that help define the “what” and “how” of an improvement project (in this case an audit).

The questions are:

- "What are we trying to accomplish?" – the aim

- "How will we know that a change is an improvement?" – what measures of success will be used?

- "What changes can we make that will result in improvement?" – the concept to be tested

2. The PDSA cycle

This is often referred to as the “engine” for creating, testing and carrying out the proposed changes. More than one cycle is usually required; each one is intended to be short, rapid and frequent, with the results used to inform and refine the next. This allows an ongoing process of continuous learning and improvement.

Each PDSA cycle includes four stages:

- Plan – decide what the change to be tested is and how this will be done

- Do – carry out the plan and collect the data

- Study – analyse the data, assess the impact of the change and reflect on what was learned

- Act – plan the next cycle or implement the changes from your plan

Claiming credits for Te Whanake CPD programme requirements

Practice or clinical audits are useful tools for improving clinical practice and credits can be claimed towards the Patient Outcomes (Improving Patient Care and Health Outcomes) learning category of the Te Whanake CPD programme, on a two credit per learning hour basis. A minimum of 12 credits is required in the Patient Outcomes category over a triennium (three years).

Any data driven activity that assesses the outcomes and quality of general practice work can be used to gain credits in the Patient Outcomes learning category. Under the refreshed Te Whanake CPD programme, audits are not compulsory and the RNZCGP also no longer requires that clinical audits are approved prior to use. The college recommends the PDSA format for developing and checking the relevance of a clinical audit.

To claim points go to the RNZCGP website: www.rnzcgp.org.nz

If a clinical audit is completed as part of Te Whanake requirements, the RNZCGP continues to encourage that evidence of participation in the audit be attached to your recorded activity. Evidence can include:

- A summary of the data collected

- An Audit of Medical Practice (CQI) Activity summary sheet (Appendix 1 in this audit or available on the

RNZCGP website).

N.B. Audits can also be completed by other health professionals working in primary care (particularly prescribers), if relevant. Check with your accrediting authority as to documentation requirements.