View / Download pdf version of this article

View / Download pdf version of this article

Every year in New Zealand, it is estimated that hundreds of thousands of subsidised medicines are dispensed to patients

and never used. These medicines often end up accumulating in people’s homes, where they can cause safety issues such as

accidental or intentional overdose, inappropriate sharing of medicines or use of expired medicines which may no longer

be effective. If medicines are inappropriately disposed of they can also cause environmental pollution, e.g. if placed

in household rubbish or flushed down the toilet.

Medicines are wasted for various reasons, including unintentional oversupply, non-adherence, changes in treatment or

dose, allergic reaction or intolerance to the medicine, resolution of the condition or death of the patient. In a New

Zealand survey completed by 452 people, 56% reported that they collect all items prescribed by their doctor, and just

over 25% collect all medicine repeats, even if the medicine is no longer needed or wanted.1 Only 13% of respondents

reported that they returned unwanted medicines to a pharmacy.1

Regular review to check the appropriateness of, and adherence to, long term medicines is not only essential clinically

but is one of the most important ways to prevent wastage. There are various other strategies that can also be undertaken

by prescribers, pharmacists and patients to reduce medicine wastage and prevent “piles of pills” creating a safety issue

in homes, including:

- Prescribing new medicines for trial periods only in case they are not continued due to intolerability or ineffectiveness

- Prescribing appropriate quantities of “as required” medicines

- Encouraging patients to put prescription items on hold at the pharmacy if they are not currently required

- Prescribing smaller quantities of “safety medicines” which may pose a risk to certain patient groups

- Considering if a patient is eligible and likely to benefit from being registered under the Long Term Condition (LTC)

scheme managed by community pharmacists

For further information on each of these strategies, keep reading.

For further information on each of these strategies, keep reading.

An underlying component of all of these strategies is patient education and support, i.e. ensuring that the patient

understands what medicines they are prescribed, what they are for and how to use each medicine correctly. In 2009 the

Nelson Marlborough DHB ran a “Discarding Unwanted Medicines through Pharmacies” (DUMP) campaign, which included a questionnaire

for patients on why they were returning unwanted medicines. Several patients commented that they did not take some of

their prescribed medicines at all even though they were required (e.g. amoxicillin, bisacodyl and naproxen), because they

were afraid of experiencing the adverse effects that they were warned about. In this scenario, non-adherence and medicine

wastage was an unintended consequence of providing patients with adverse effect information, but not checking that they

understood that it was still important that they took the medicine. This highlights the need to ensure that patients are

not only provided with information about their medicines, but that they also comprehend the information that they are

given.

Ask patients about their medicines

Whenever medicines are prescribed or dispensed there should be a conversation with the patient about their use of each

medicine. Try to ask questions such as those below in an open-ended manner to avoid patients responding with the answer

that they “expect” you want. If medicines are no longer required or not being used (and this non-adherence is appropriate),

consider “de-prescribing”.

Prescribers:

- Ask what medicines* the patient has at home before prescribing more

- Ask if they are using each medicine they have been prescribed

- Ask if they are experiencing any adverse effects or difficulties with taking any of their medicines

* include all options, e.g. pills, inhalers, topical preparations and also over-the-counter products

Pharmacists:

- Ask the patient if they require all of the medicines on their prescription before they are dispensed

- Ask if they know what their medicines are for

- Ask if they have any concerns or questions about the medicines they have been dispensed

Trial periods for new medicines

In surveys of medicine wastage, a common reason for the return of unused medicines is a change in dose or a change to

a different medicine. There are several clinical scenarios where initiating pharmacological treatment for a patient is

a “trial and error” process, e.g. managing hypertension. This can lead to medicine wastage if a 90-day supply of a new

medicine is dispensed, but the medicine dose or type needs to be changed within a week or two.

If it is uncertain if a medicine will be continued, consider prescribing it for a trial period only. It is possible

to use the “trial period” dispensing provision of the Pharmaceutical Schedule to allow dispensing of a small portion of

the first supply of a new or changed dose of medicine, to check acceptability and tolerability of the medicine for the

patient.

If the trial of treatment goes well, the patient can contact their pharmacist so that they can dispense the remainder

of the prescribed medicine; this is at no additional cost to the patient provided the medicine is fully subsidised. Ideally

the patient should also contact their doctor, particularly if they have had problems while taking the new medicine. If

a different dose or medicine is likely to be required, this can be discussed or a consultation can be scheduled. A reminder

placed in the patient’s notes at the start of the trial period can be used to ensure that the outcome of the trial is

documented and to check that the patient has correctly understood the reason for the trial and is continuing on the medicine

or has a review in place.

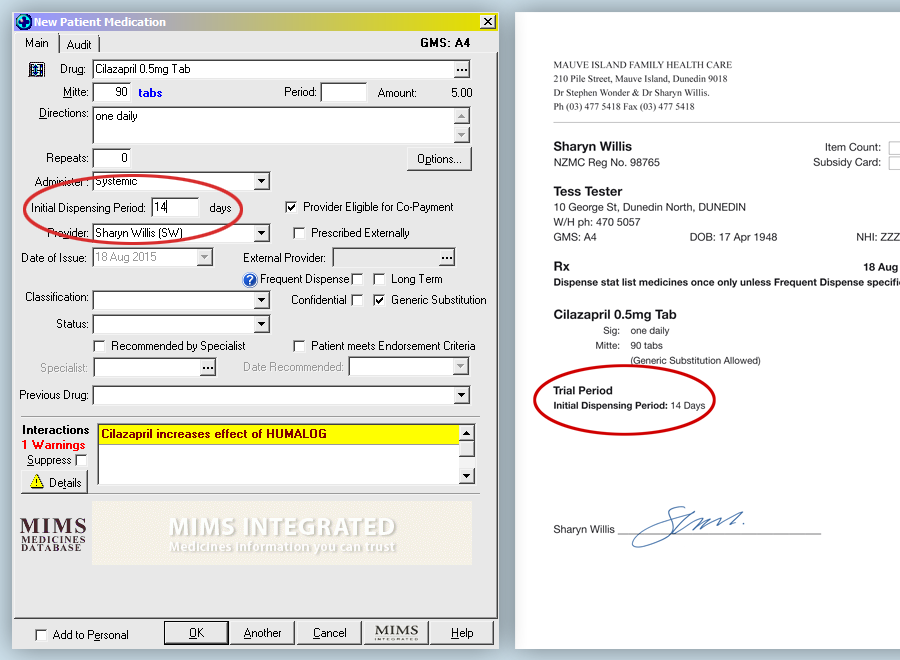

Example of how a trial prescription can be written:

- Rx Cilazapril 500 microgram tablets*

- Sig 1 tablet daily

- Mitte 3 months, Trial 30 days

The prescription must be endorsed with the words “Trial period” or “Trial” and the quantity or time for the trial specified.

This can be done when generating a prescription using Medtech by entering a number of days for an initial dispensing

period in the provided box. The prescription will then be printed with a specified Trial Period.

See example below.

In the scenario given for cilazapril, it is recommended that the patient be seen at the practice during the trial period

so their blood pressure can be re-checked. This also provides an opportunity for laboratory assessment if required, e.g.

renal function. N.B. When checking for adverse effects during the trial period for a patient taking cilazapril, an ACE

related cough may or may not develop within one month.

*In the Pharmaceutical Schedule, the status of a medicine with regards to its dispensing frequency is indicated with * or ▲ beside the name of the medicine.

In the New Zealand Formulary, this information can be found by hovering over the word ‘restrictions’ beside a medicine’s listing, where it will say:

“Statim: Three months or six months, as applicable, dispensed all-at-once”.

Appropriate quantities for “as required” medicines

PHARMAC subsidy regulations require pharmacists to dispense 90-day single “stat” supply for many medicines (or 180 days

for oral contraceptives); other medicines (often more costly medicines) must be dispensed in monthly quantities.

(see: What are the Pharmaceutical Schedule rules regarding the dispensing of medicines in the community?)

The 90-day supply requirement also applies to medicines that are prescribed “as required” (also known as p.r.n. – pro

re nata). This can lead to unnecessarily large quantities of medicines being dispensed, if the prescriber does not specify

an amount to be dispensed on the prescription. Depending on the medicine, this can pose a safety risk to the patient and

their family, as well as contributing to medicine wastage.

It is recommended that when a medicine is prescribed “as required”, prescribers decide on and specify the appropriate

quantity (e.g. of tablets or inhalers) to be dispensed. As well as minimising wastage, this provides clinicians with an

opportunity to reassess the patient in a follow up phone call or return consultation, if they require more medicine than

expected.

Examples of appropriate quantities for “as required” medicines

Example 1: Laxatives

A patient requires a laxative on an intermittent but ongoing basis and is given the following standard prescription:

- Rx Docusate and senna (Laxsol)

- Sig 1 – 2 tablets prn, morning and night

- Mitte 3 months

The pharmacist dispensing this prescription could dispense a total of 360 tablets (to allow for up to four tablets per

day for 90 days). The pharmacist should discuss the amount required by the patient and use their clinical reasoning when

deciding on the frequency and quantity on each dispensing, but ideally the prescriber should first consider if this is

an appropriate quantity for the patient to be supplied before they are reviewed again.

Suggested alternative prescription:

- Rx Docusate and senna (Laxsol)

- Sig 1 – 2 tablets prn, morning and night

- Mitte 200 tablets

This quantity of tablets will provide the patient with enough to take one tablet twice daily, regularly, with 20 extra

tablets for the occasional higher dose.

Example 2: Analgesia

Paracetamol is often prescribed “as required” for analgesia, e.g:

- Rx Paracetamol 500 mg tablets

- Sig 1 – 2 tablets q4h prn, up to qid

- Mitte 3 months

The pharmacist will dispense a total of 720 tablets if the prescription is written in this way. This is appropriate

if the intention of the prescriber is for the patient to take 1 g paracetamol on a regular basis, four times daily, for

three months, e.g. for osteoarthritis. However, it is worth considering if this quantity is appropriate for the patient

you have in front of you – what is the paracetamol being prescribed for? Is the intention that the paracetamol be used

occasionally, when required, and not continuously? Is it safe for this household?

Suggested alternative prescription:

- Rx Paracetamol 500 mg tablets

- Sig 1 – 2 tablets q4h prn, up to qid

- Mitte 180 tablets

This quantity provides the patient with enough supply to take two tablets, twice daily, for a few days a week over a

three month period, e.g. for intermittent headaches or pain, or two tablets, four times daily, for approximately three

weeks, e.g. for an injury.

Example 3: Asthma inhalers

Asthma reliever inhalers, such as salbutamol, are most often prescribed “as required”. Ideally, patients with asthma

will be well controlled with preventive medicines and will require reliever medicines infrequently. If a patient is requiring

frequent prescriptions for reliever inhalers, this is an indication that they may not be using their preventer inhaler

optimally, or at all.

A typical prescription for salbutamol is:

- Rx Salbutamol inhaler 100 microgram/puff

- Sig 1 – 2 puffs prn, up to qid

- Mitte 3 months

In this example prescription the pharmacist would dispense four salbutamol inhalers to cover 56 doses per week (200

doses per inhaler) over three months, most likely as two inhalers in the first month and a further one in the second and

third months: 2+1+1 (as salbutamol is not a stat medicine). N.B. The Pharmacy Procedures Manual states that a maximum

of six inhalers (1,200 doses) will be subsidised and these should be dispensed according to the patient’s needs, e.g.

as 2+2+2 or 3+2+1 or 4+1+1.3 Would it be more appropriate for the patient if they were prescribed only one

or two salbutamol inhalers and to monitor requests for additional salbutamol inhalers?

Suggested alternative prescription:

- Rx Salbutamol inhaler 100 microgram/puff

- Sig 1 – 2 puffs prn, up to qid

- Mitte 2 inhalers

The appropriate quantity of inhalers to prescribe is determined by the intended frequency of use, which will differ

with the individual requirements of the patient. If their asthma is well controlled with a corticosteroid inhaler you

would expect them to only need one salbutamol inhaler every three to six months. However, a patient may require a larger

quantity of reliever inhalers to account for more doses during winter months if they contract a respiratory tract infection,

or during “hay fever season” if they have concurrent allergic rhinitis, but may require fewer inhalers at other times

during the year. Patients may also require an extra inhaler for their car or sports bag, but will not require this extra

amount every prescription.

Best Practice Tip: Different types of asthma inhalers vary in the number of doses they contain, e.g. most reliever inhalers

contain 200 doses; corticosteroid inhalers, long-acting beta2 agonist inhalers and combined inhalers usually contain 60,

112 or 200 doses, inhalers that require insertion of a capsule containing the dose usually contain 28 or 30 doses. Make

sure the number of inhalers (or capsules for inhalers) indicated on a prescription will provide enough quantity to deliver

the intended number of doses for the time frame indicated.

Best Practice Tip: Different types of asthma inhalers vary in the number of doses they contain, e.g. most reliever inhalers

contain 200 doses; corticosteroid inhalers, long-acting beta2 agonist inhalers and combined inhalers usually contain 60,

112 or 200 doses, inhalers that require insertion of a capsule containing the dose usually contain 28 or 30 doses. Make

sure the number of inhalers (or capsules for inhalers) indicated on a prescription will provide enough quantity to deliver

the intended number of doses for the time frame indicated.

What are the Pharmaceutical Schedule rules regarding the dispensing of medicines in the community?

The rules relating to how medicines are dispensed are set out in various sections of the Pharmaceutical Schedule. Section

A: General Rules sets out the requirements for the subsidy and dispensing of community pharmaceuticals while Section F

provides additional information on exemptions to monthly dispensing. The Dispensing Frequency Rule (Part IV under Section

A) was introduced in July, 2012 to replace the Close Control Rule and was further amended in June, 2014.

N.B. The prescribing module of your PMS system may not currently contain up to date information stating which medicines

are required to be dispensed all-at-once or identification of those medicines listed as “safety medicines”.

Pharmaceutical dispensing rules:

- If a prescription item is marked with an asterisk * in the Pharmaceutical Schedule, three months supply of the medicine

will be dispensed all-at-once or, in the case of oral contraceptives, six months will be dispensed all-at-once,

unless the medicine meets the Dispensing Frequency Rule criteria (see opposite). Items marked with an * will only be

subsidised if they are dispensed in a 90 Day Lot.

- A prescription item marked with a triangle ▲ in the Schedule may be dispensed in a three month supply all-at-once

if the prescription is endorsed “certified exemption” by the prescriber or the pharmacist, e.g. gabapentin

- Community Pharmaceuticals not marked with an * or a ▲, will be dispensed in monthly lots. These medicines may be dispensed

in a 90 Day Lot if the practitioner or pharmacist endorses the prescription with the words “certified exemption”

or if the patient qualifies for an Access Exemption due to factors such as poor mobility, distance from the pharmacy,

relocation or travel. The prescription must be signed on the back by the patient and the reason identified.

- The Dispensing Frequency Rule defines the medicines or patient groups that are eligible for more frequent dispensing

(usually monthly) and outlines the conditions that allow for the pharmacy to claim payment for the additional

dispensings. This rule allows more frequent dispensing in the following circumstances:

- Patients who are eligible for the Long Term Condition (LTC) service

- Non-LTC (core) patients as determined by the pharmacist if monthly dispensing or with approval by the prescriber

if more frequent than monthly

- People in residential care

- Trial periods

- Items identified as “safety medicines” (and co-prescribed items)

- Pharmaceutical supply management

In practice, these rules mean that if you have been prescribing an item marked in the Schedule with an *, e.g. paracetamol,

as “mitte 100 tablets + 2 repeats” it is likely that the patient will have been dispensed 300 tablets at the initial dispensing

with no repeats dispensed. However, if the pharmacist has considered that more frequent dispensing is warranted (as outlined

above) the patient may have received 100 paracetamol tablets each month. On your electronic prescribing system, there

is likely to be a box to tick for “Frequent Dispense” replacing the one that used to be ticked for “close control”, which

is no longer relevant (N.B. this annotation does not need to be initialled.) This can give an indication to the pharmacist

that the prescriber feels more frequent prescribing is required and provided that the patient or the medicine are eligible

under the Dispensing Frequency Rule, this will enable the items to be dispensed monthly. For many patients, stat prescribing

of prescription items will save them repeated trips to the pharmacy, but for others where there may be safety issues in

particular, the prescriber and pharmacist should work together to determine the appropriate prescribing frequency.

Separate rules continue to apply to dispensing of Class B Controlled drugs.

Putting prescription items on hold

When a patient presents a prescription at a pharmacy, any item on the prescription can be held at the pharmacy for up

to three months, and dispensed at a later date if needed. This is a useful strategy for minimising medicine wastage, if

a medicine is prescribed at the time of a consultation, but it is uncertain whether the medicine will be needed by the

patient. This might be done to avoid the patient having to return for another consultation. For example, a patient who

takes omeprazole on as “as needed” basis rather than daily may have this added to their prescription, but instructed to

tell the pharmacist to hold it for them and only dispense it if the patient’s existing supply runs out. An alternative

strategy is to write the prescription item on a separate page from the other items, and instruct the patient to only have

it dispensed if they require it; a prescription is eligible for subsidy if it is presented within three months from the

date it was written. Ideally a notification or communication from the pharmacist would allow the prescriber to document

whether or not a prescription has been dispensed. This may become more common place as electronic prescribing systems

evolve and information is able to be more quickly and easily shared.

It is useful for the pharmacist also to ask patients if they require all of the medicines on their prescription to be

dispensed. If a patient repeatedly asks their pharmacy to not dispense a medicine, however, and there is a concern about

their adherence with prescribed medicines, the pharmacist should discuss this with the prescriber.

Prescribing safety medicines

Decisions around quantities of medicines prescribed often factor in financial considerations for the patient, i.e. wanting

to provide people with an adequate, but not excessive, quantity of medicine for their condition taking into account the

cost of the prescription and the visit they have made to the clinician, while minimising unnecessary additional costs.

However, the quantities of medicines that will be stored in homes, and may not be used, should also be kept in mind. The

“Safety Medicine” provision of the Pharmaceutical Schedule has been designed to minimise dispensing large quantities of

high-risk medicines with no financial penalty to the patient.

What is a Safety Medicine?

Many medicines on the Pharmaceutical Schedule have a default dispensed quantity of 90 days’ supply. However, there are

a number of “Safety Medicines” that can be dispensed in smaller than 90-day stat quantities at no extra cost to the patient,

if the maximum supply quantity or period of supply is specified by the prescriber on the prescription, or is otherwise

communicated to the dispensing pharmacist. This strategy is aimed at limiting the supply quantities of medicines that

pose a particular clinical risk to patients who, for example, have difficulty managing their medicines, patients who may

be at risk of intentional overdose, or who may be inclined to use the medicines inappropriately or in an unsafe way.

Safety Medicines are identified in the Pharmaceutical Schedule with the words “Safety Medicine” written alongside the

medicine’s listing; the current Safety Medicines are:

- Antidepressants listed under the “cyclic and related agents” subheading, e.g. amitriptyline, clomipramine, doxepin,

imipramine, nortriptyline

- Antipsychotics

- Benzodiazepines*

- Zopiclone

- Class B Controlled Drugs, e.g. methylphenidate, morphine

- Codeine (a class C2 Controlled Drug) including paracetamol 500 mg with codeine 8 mg tablets

- Buprenorphine with naloxone (Suboxone, a class C4 Controlled Drug)

* A previous requirement that benzodiazepines had to be prescribed for a maximum of a 30-day supply per prescription

was changed in 2010; benzodiazepines are now Safety Medicines, for which an appropriate dispensing quantity or frequency

can be specified by the prescriber.

How do you prescribe a Safety Medicine?

Prescribe the medicine in the usual way and specify a maximum quantity of the medicine to be supplied to the patient

on each dispensing (e.g. 90 tablets in total, supplied 30 tablets at a time) or time period of supply (e.g. supply tablets

for 90 days in total, 30 days at a time).

Co-prescribed medicines are medicines that are prescribed at the same time as a Safety Medicine, e.g. regular

cardiovascular or diabetes medicines; the dispensing pharmacist can choose to dispense these at the same time as the Safety

Medicine if they judge that this is safer for the patient’s circumstances.

Understanding prescription charges

The current prescription co-payment is $5 per medicine item if the medicine is fully subsidised in the Pharmaceutical

Schedule. The $5 co-payment fee is paid by the patient the first time the prescription is dispensed; any medicines on

the prescription that require repeat dispensing (e.g. medicines prescribed for more than 30 days) do not have another

co-payment payable until the next prescription is written. The maximum number of $5 prescription co-payments for an individual

or a family group is 20 per year* provided the same pharmacy has been used or receipts from other pharmacies have been

presented to their regular pharmacist; this information is recorded in pharmacies but it is up to the patient to pass

the information on if they are using more than one pharmacy to dispense their medicines.

* A year being defined as from 1 February until 31 January in the following year

Manufacturer’s surcharges are payable by the patient when the medicine they are prescribed is only partially

subsidised or is not listed at all in the Pharmaceutical Schedule. The manufacturer’s surcharge is calculated per unit

of medicine although this may vary between pharmacies, and is in addition to the $5 prescription co-payment. This reiterates

the importance of specifying appropriate quantities of “as required” medicines, to minimise unnecessary costs for patients.

Consider eligibility for the Long Term Condition service

The Long Term Condition (LTC) service was introduced in 2012 as part of a number of changes under the Pharmacy Services

Agreement. General practitioners, other health professionals or family members can contact or refer a patient to a pharmacist

to assess whether the patient may be eligible for this service. Patients may also self-refer.

A pharmacist will determine if the patient qualifies to be registered as a LTC patient. To be eligible the patient must

live in the community and have at least one long term condition that requires medicine as part of its management. The

patient then needs to have been either referred for assessment by a general practitioner or have contact with another

allied health service, e.g. district nursing, secondary care, or have had concerns about their ability to self-manage

their medicines identified by the pharmacist, family or the patient themselves. In addition, there must be evidence that

the patient collected less than 80% of their regular medicines over the past six months or that despite collection there

are concerns regarding adherence or the patient has had a recent review of their medicine use which has identified that

support and monitoring is required.

Once eligibility has been determined and the patient’s consent obtained, the pharmacist will undertake a review with

the aim of assisting the patient with management of the medicines relating to their LTCs. This is likely to include an

assessment of factors that may be affecting adherence, determining an appropriate dispensing frequency and increasing

the patient’s understanding of their medicines and how to use them.

For further information on the LTC Service see:

www.centraltas.co.nz

For further information on the LTC Service see:

www.centraltas.co.nz

A number of helpful resources can be accessed here under the Community Pharmacy Programme section of the website including

the LTC Service Protocol, the LTC Service Eligibility and Assessment tool used by pharmacists and a “Guide to the Community

Pharmacy LTC Service”.

How to appropriately dispose of unwanted medicines

Patients should be advised to take their unwanted medicines (both prescribed and self-purchased) to a pharmacy for safe

disposal. In most areas, DHBs fund the collection and disposal of unwanted medicines with pharmacies acting as the depot

and sorting area; pharmacies should ensure that they are familiar with local protocols and adherent with correct disposal

guidelines. In a New Zealand survey completed by 265 community pharmacists, 80% said that they disposed of returned tablets

and capsules via third party contractors (i.e. the DHB-funded disposal service) and 61% said they disposed of ointments

and creams in the same way.2 However, 45% reported that they pour returned liquid preparations down the sink

and 7% flush liquid preparations down the toilet.2

“Discarding Unwanted Medicines through Pharmacies” (DUMP) campaigns are periodically run by DHBs in conjunction with

community pharmacies, using media and other publicity about medicines safety to raise community awareness.

Returned medicines (e.g. to pharmacies or general practice clinics) cannot be reused or donated if the storage conditions

and integrity of the medicine cannot be guaranteed. N.B. Some practices may participate in schemes for forwarding a variety

of unused medicines to developing countries. Medicines should be of original quality, stored correctly and not expired;

ideally medicines should have a remaining shelf-life of at least 12 months. For example,

see: www.maa.org.nz

For further information, see:

“Waste not want not: reducing wastage”, BPJ 23 (Sep, 2009).

For further information, see:

“Waste not want not: reducing wastage”, BPJ 23 (Sep, 2009).

References

- Braund R, Peake B, Shieffelbien L. Disposal practices for unused medications in New Zealand. Environ Int 2009;35:952–5.

- Tong A, Peake B, Braund R. Disposal practices for unused medications in New Zealand community pharmacies. J Prim Health Care 2011;3:197–203.

- Community Pharmacy Services. Pharmacy Procedures manual – a guide to payment and claiming. Version 7.0. 2015. Available

from: www.centraltas.co.nz (Accessed Aug, 2015).