Published: 14th October 2024

Key practice points:

- Long-term smoking cessation can reverse many smoking-associated adverse health outcomes and provides immediate quality of life benefits. However, breaking the cycle of nicotine dependence is a significant challenge that often requires external support.

- Ask about and record the smoking status of all patients during routine primary care consultations. This should be re-assessed regularly where possible, particularly among patients aged under 30 years, or anyone identified as being a current smoker or ex-smoker.

- All patients who smoke should be briefly advised about the importance of quitting. Cessation support should be discussed and strongly encouraged for every person who smokes, regardless of their desire to quit.

- Healthcare professionals should offer to help patients access cessation support services, i.e. refer them or explain how they are accessed

- The delivery of smoking cessation advice and offer of support should also be recorded in the patient’s clinical record (see main text for codes)

- For patients who want to quit smoking, always offer both behavioural and pharmacological support. Behavioural support can be delivered by cessation support services (e.g. Quitline or local stop smoking services) and supplemented with clinician input. However, in some cases, primary healthcare professionals may be the key provider of behavioural support.

- Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is usually the first-line pharmacological treatment for people who want to quit. If a patient is not ready to completely stop smoking, NRT can also be used to help progressively reduce the amount they smoke prior to quitting.

- Combination NRT (e.g. patches plus gum or lozenges) is the most effective approach and is most suitable for patients with higher levels of nicotine dependence (e.g. those who smoke within one hour of waking or smoke ten or more cigarettes per day)

- Single form NRT can be used in patients with a lower level of nicotine dependence

- If a person experiences a lapse in their quit attempt, behavioural support, continued use of NRT (or consideration of other smoking cessation medicines) and regular follow up increases their chances of stopping long-term

- Bupropion, nortriptyline and varenicline are other pharmacological options for smoking cessation. Varenicline is the most effective of these treatments and has slightly higher efficacy compared with combination NRT. It is funded with Special Authority approval for patients who have previously tried to quit with other smoking cessation medicines. However, varenicline has been unavailable in New Zealand for some time. It has been reported that it may be back in stock by late March, 2025.

Smoking is associated with a higher burden of disease than any other behavioural risk factor, surpassing the effects of alcohol consumption and unhealthy or excessive eating.1 All primary healthcare professionals will be familiar with the broad scope of this issue and the importance of encouraging patients to quit smoking. However, broaching these conversations and supporting patients to change an often deeply ingrained aspect of daily life can be a significant challenge.

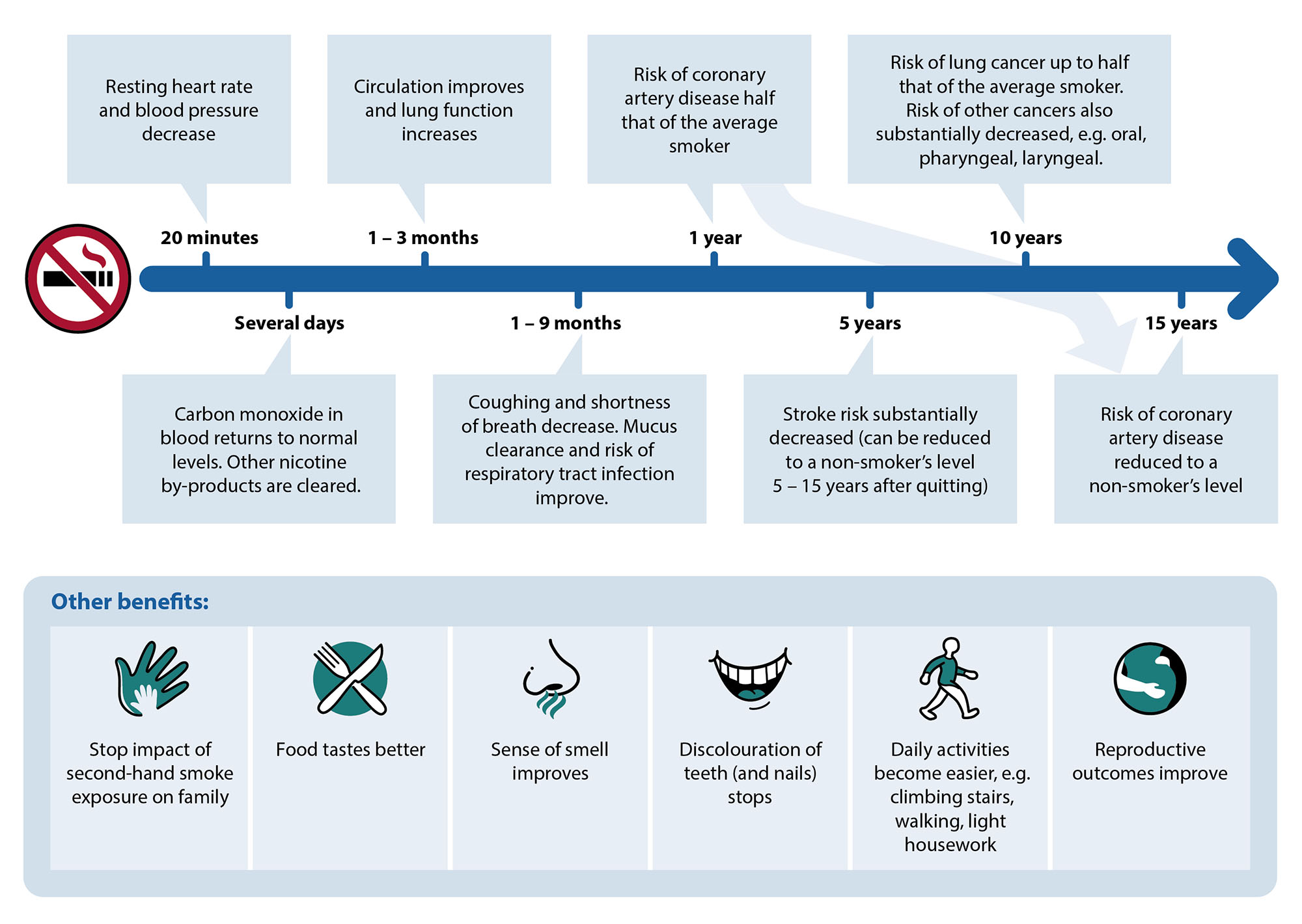

Smoking causes considerable harm (see: “The importance of overcoming a deadly habit: the harms caused by smoking and progress towards smokefree goals”), but evidence suggests that cessation has both immediate and long-term benefits on a person’s health and quality of life (Figure 1).2, 3 The greatest effect is achieved by people who quit at a younger age, and if smoking cessation occurs early enough, it can improve life expectancy by almost ten years (compared to if they continued smoking).2 However, quitting smoking at any age will lower the risk of morbidity and mortality; given enough time, the risk of some adverse health outcomes can return to the level of non-smokers, e.g. the risk of coronary artery disease returns to baseline after 15 years of smoking cessation.2, 3

Figure 1.The health benefits of smoking cessation.2

Breaking the cycle of smoking/nicotine use is challenging

Regular smoking results in neuroadaptation, which leads to nicotine dependence.4 When a patient first experiments with smoking, nicotine from cigarettes exerts both reinforcing and aversive effects; the balance between these and the presence of additional risk factors (e.g. age, male sex, genetics, mental health challenges, social factors) influences the probability of continued use.4 As patterns of use increase, nicotine causes more significant changes in brain neural circuitry, resulting in a lower sensitivity to nicotine’s aversive properties, and reinforcing the pathways that drive regular intake, e.g. dopamine release.4 When smoking is stopped, nicotine levels decrease and the associated dependence manifests as cravings and urges to smoke, as well as withdrawal symptoms, such as irritability, low mood/anxiety, poor concentration and difficulty sleeping 4

For these reasons, only a small proportion of people who achieve long-term abstinence from smoking do so on their first attempt; most cycle through multiple quit attempts, which will be fewer if they have external help, e.g. from a healthcare professional, family/whānau friends, smoking cessation service.1 One longitudinal study (N = 1,277) estimated that people who smoke average up to 30 cessation attempts before successfully quitting for one year or longer.5 This illustrates the significant challenge faced by patients when trying to quit smoking; it is important to acknowledge difficulties upfront and ensure they have access to consistent support throughout their attempt. Even once a person “quits”, ongoing positive reinforcement and encouragement is essential to facilitate long-term cessation, particularly at times of crisis or when urges to smoke occur (often provoked by cues such as seeing someone smoking or the image of a cigarette brand).

Most people who smoke want to quit and anticipate being asked questions about their smoking status by healthcare professionals.6 The Ministry of Health recommends use of the ABC pathway to maximise opportunities for smoking cessation and to increase the success of quit attempts:1, 6, 7

sk about the smoking status of every patient and document this information in their clinical record

sk about the smoking status of every patient and document this information in their clinical record

- The way this question is asked can be tailored depending on what is known about the patient, e.g. bringing it up in the context of co-morbidities or illness (e.g. respiratory symptoms), family circumstances, financial pressures

- Define the smoking status criteria when asking this question, as people may interpret terms in different ways, e.g. “social smokers” may smoke weekly or fortnightly, yet not consider themselves “current smokers”

- Ensure all clinicians within the practice understand the distinction between different smoking status definitions and consistently use the correct codes:

| |

Definition

|

SNOMED CT term

|

SNOMED CT code

|

Read code

|

|

Non-smoker

|

Smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in lifetime (including hand rolled cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos)

|

Never smoked

|

266919005

|

1371

|

|

Ex-smoker

|

Smoked more than 100 cigarettes in lifetime but has not smoked in the previous 28 days

|

Ex-smoking for less than 1 year*

|

735128000

|

137K

|

|

Ex-smoking for more than 1 year

|

48031000119106

|

137S

|

|

Current smoker

|

Smoked more than 100 cigarettes in lifetime and has smoked in the previous 28 days

|

Currently smoking

|

77176002

|

137R

|

* This distinction is used as the risk of smoking relapse reduces significantly after 12 months

N.B. Vaping status should also be routinely considered in addition to smoking status. For codes and further discussion around vaping, see: “What about vaping as an alternative to smoking?”

- The patient’s smoking status should be re-assessed regularly (e.g. annually), particularly among patients aged under 30 years, or anyone identified as being a current smoker or ex-smoker

riefly advise every person who smokes to stop, regardless of their desire or motivation to quit

riefly advise every person who smokes to stop, regardless of their desire or motivation to quit

- The delivery of brief opportunistic advice from healthcare professionals increases smoking cessation rates by at least 66% versus no intervention.8 Advice can be delivered in as little as 30 seconds, but a more significant effect is observed when more “intensive” advice is provided.

- In general, opening with positive or gain-framed statements is a more successful strategy than the use of loss-framed statements.9 For example, focus on the health and quality of life benefits (Figure 1), financial savings and reassure patients that cravings decrease over time, rather than saying “smoking harms your health”. However, advice should always be tailored to the specific patient and their circumstances, and loss-framed statements often are still part of the continued conversation.

- Acknowledge that quitting can be difficult, but it is achievable

- Record the delivery of advice in the clinical record:

| |

SNOMED CT term

|

SNOMED CT code

|

Read code

|

|

Delivery of brief advice to stop smoking

|

Brief smoking cessation advice

|

771155005

|

@ZPSB.10

|

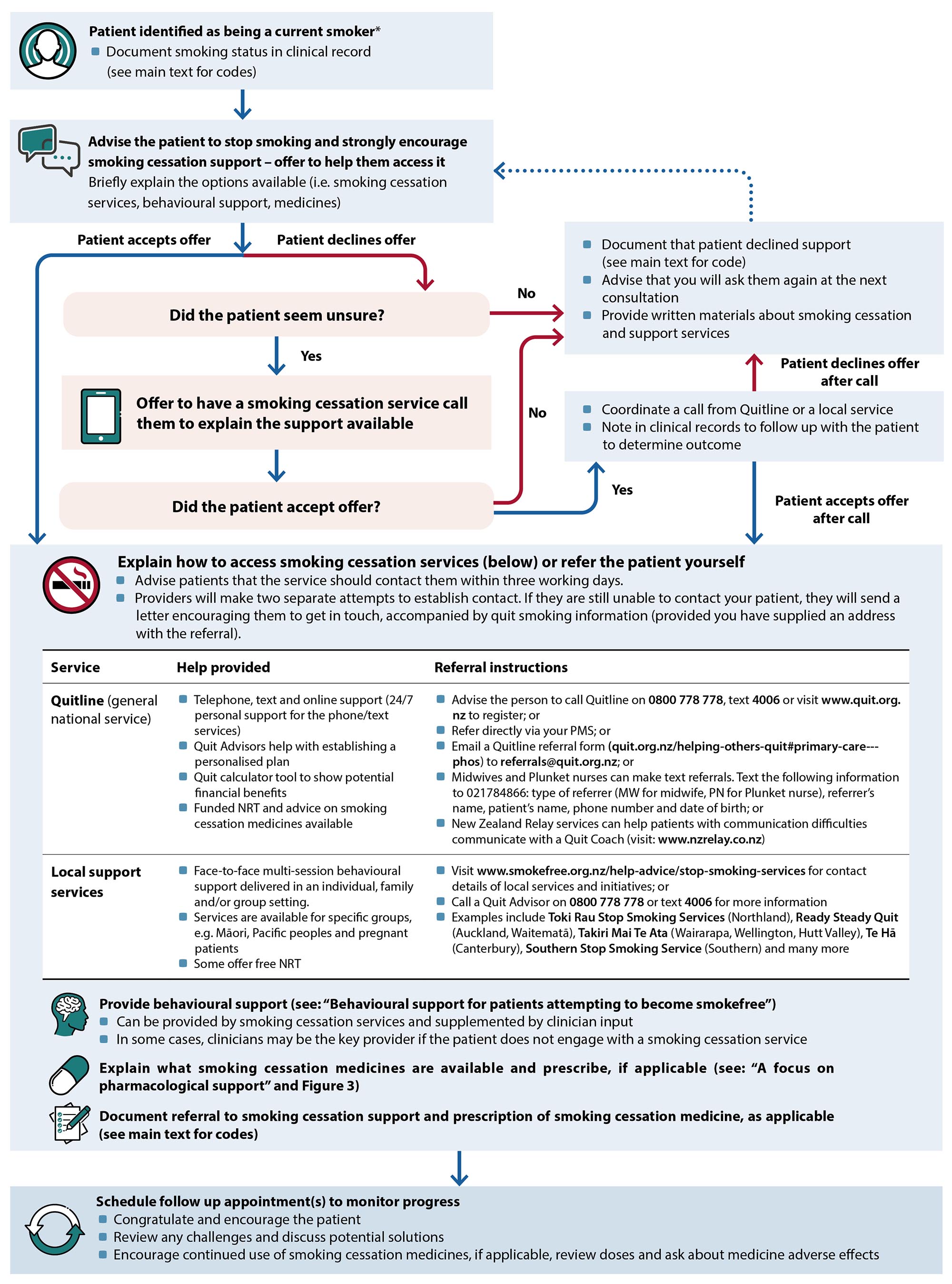

essation support should be discussed and strongly encouraged for every person who smokes. Healthcare professionals should offer to help patients access cessation support services, i.e. refer them or explain how they are accessed. Figure 2 provides an overview for how this process may unfold in a primary care setting, including addressing situations where patients are ambivalent about quitting smoking.

essation support should be discussed and strongly encouraged for every person who smokes. Healthcare professionals should offer to help patients access cessation support services, i.e. refer them or explain how they are accessed. Figure 2 provides an overview for how this process may unfold in a primary care setting, including addressing situations where patients are ambivalent about quitting smoking.

Figure 2. An overview of how primary healthcare professionals can offer smoking cessation support and the options available.1, 6

* Patients identified as having recently quit smoking (e.g. within the previous year) should still be asked whether they need help to remain smokefree, and appropriately supported if the answer is “yes”

NRT, nicotine replacement therapy; PMS, practice management system; SNOMED CT, systematized medical nomenclature for medicine clinical terminology

Factors affecting ABC pathway delivery and success

|

Facilitators 6 |

|

Training. Engaging in dedicated smoking cessation training improves the odds of success when delivering the ABC pathway (this includes staff induction and refresher training, ideally annually). Cultural safety training is also important to promote equitable outcomes.

Information on accessing smoking cessation professional development is available at: www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/for-health-professionals/clinical-guidance/specific-life-stage-health-information/child-health/well-child-tamariki-programme/te-mahau-tarearea-o-tamariki-ora/smoking-cessation/

|

|

System prompts. Use tools within your PMS to prompt the provision and recording of the different ABC pathway components. There may also be web-based applications that can be used to assist this process.

|

|

Auditing performance and feedback are effective approaches for making and maintaining changes in clinical behaviour

A clinical audit on smoking cessation for primary care is available at: www.bpac.org.nz/audits/smoking.aspx

|

|

Leadership. General Practices and pharmacies should promote a smokefree culture within their workplace and to the population they care for; this requires healthcare professionals to advocate for and to support smoking cessation initiatives.

|

|

Barriers 6

|

|

Healthcare professionals who smoke may have different attitudes towards smoking and providing cessation support. Practices should offer cessation support to colleagues who smoke.

|

|

Perceived lack of time. The ABC pathway can be implemented within a few minutes. Face-to-face delivery is ideal, but it can be delivered over the phone if this is not possible, e.g. time constraints, patients without regular appointments. Sending texts or letters can only be considered an offer of support (and coded as such) if the patient replies, either to decline or accept/seek further information.

|

All patients who accept an offer of cessation support should be provided with behavioural support. This involves:6

- Maximising the patient’s motivation to stop smoking and remain smokefree

- Equipping them with skills and strategies to identify and manage smoking triggers and resist cravings

- Optimising the effective use of smoking cessation medicines (see: “A focus on pharmacological support”)

Behavioural support can be delivered by a smoking cessation service provider (either individually or in a group setting) and supplemented by input from the primary care team (Figure 2).1, 6 However, in some cases, the general practice may be the key provider if the patient does not engage with a smoking cessation service.

For a list of initial “Quitting Tips”, see: https://quit.org.nz/stay-smokefree#tips-for-quitting.

A key feature of behavioural support is providing education and correcting mistaken beliefs that make it more difficult for people to stop smoking (Table 1).1, 4 ,9 An adaptable approach is required, with consideration given to the patients background and any underlying cultural factors or values that may influence their decisions or present ongoing barriers to successfully quitting.6 Other behavioural interventions with evidence for improving the success of cessation attempts include setting a “quit date”, positive feedback from a health professional, text messaging support (this can be provided by Quitline), psychological support and counselling.1, 10

Practice point: Encourage the patient to set a “quit date”, which can provide them with a point of focus and feeling that they are “taking control”. Having a defined quit date is also important in the context of smoking cessation medicine dosing (see: “A focus on pharmacological support”).

Table 1. Discussion prompts and strategies for addressing perceived barriers to smoking cessation in primary care.1, 4 ,9

Perceived barrier (from patient)

Including mistaken beliefs or perspectives

|

Potential response or strategy to address barrier

(from healthcare professional)

|

|

Concerns that it is too hard to quit

|

- Discuss why previous smoking cessation attempts (if any) were not successful, and what could be done differently next time

- Emphasise that external support (e.g. from the primary care team, Quitline, local services) and medicines can significantly improve the success of quit attempts

|

|

Fear that it is too late to quit and derive health benefits

|

- Explain that health benefits still occur at any age (Figure 1); these are both immediate and long-term

- Emphasise other quality of life benefits

- Provide evidence and feedback, e.g. use a CVD risk calculator and alter status from current smoker to previous smoker, use case studies to outline health benefits obtained by others

|

|

Apprehension about cravings and withdrawal symptoms, e.g. irritability, low mood/anxiety, restlessness, poor concentration, increased appetite, difficulty sleeping

|

- Reassure them that withdrawal symptoms are transient; most peak within days of smoking cessation, and disappear completely within 2 – 4 weeks

- Not everyone gets every withdrawal symptom

- NRT helps reduce the severity of withdrawal symptoms

- Plan a course of action for dealing with cravings, e.g. the “4 Ds”: delay, deep breaths, drink water, do something else

|

|

Belief that using NRT is a sign of weakness and not necessary

|

- Reframe the purpose of NRT support; it is providing the chemical their body is already used to (nicotine) without the other toxic components in cigarettes

- Highlight the difference in smoking cessation success rates with and without NRT

|

|

Belief that smoking helps reduce stress and improves their mood/mental health

|

- Explain that nicotine drives changes in the brain that cause stress in its absence (i.e. it causes stress rather than reliving it); each cigarette further contributes to this cycle of dependence

- Identify triggers for smoking and discuss other potential relaxation strategies

|

|

Concerns over potential weight gain

|

- Acknowledge that on average people gain 2 – 4 kg when quitting, but it is usually not permanent and substantial weight gain is uncommon. There are multiple contributors to weight gain after cessation, e.g. slower metabolism and increased appetite due to nicotine withdrawal, “snacking” in the place of smoking in response to cravings, food tastes/smells better

- Discuss approaches to minimise weight gain and that this may also be a good time to make other positive lifestyle changes, e.g. improve diet, increase exercise

- Highlight that even if patients gain weight, they will still be “fitter” i.e. their breathing/heart rate during daily activities will improve

|

|

Apprehension around peer and social pressure

|

- Suggest avoiding high risk situations early in the quit attempt, if possible, e.g. drinking alcohol, social encounters with others who smoke

- Rehearse ways to say no to cigarettes if offered and encourage them to ask people to stop offering cigarettes

- Having a “quit buddy”, if possible

|

NRT, nicotine replacement therapy

What about vaping as an alternative to smoking?

Vaping is likely to be substantially less harmful than smoking.11 Vaping products (sometimes called ‘e-cigarettes’), particularly those containing nicotine, may be a suitable compromise in patients who enquire about them if they have unsuccessfully tried to stop or reduce smoking using both behavioural support and smoking cessation medicines.6 Like NRT, nicotine-containing vaping products can help to address nicotine dependence, and they may also cater to some of the behavioural and social aspects of smoking.6

- Vaping in non-smokers should be strongly discouraged, particularly among adolescents

Advise that vaping is not a long-term solution. If a patient chooses to vape as a means of quitting smoking, they should be encouraged to switch completely to vaping and stop smoking cigarettes, as even low rates of smoking are harmful. However, clinicians should emphasise the importance of the patient also having a plan in place to subsequently quit vaping (due to uncertainty around the long-term health effects). There is currently a lack of RCT evidence to definitively guide vaping cessation, however, a general method is to progressively lower (taper) the nicotine content of the vaping liquid before vaping is ultimately ceased. A Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand 2020 Position Statement advises that “any e-cigarette product should also be considered an NRT therapy. There should be appropriate e-cigarette cessation advice and a supportive plan to stop the use of any NRT related product”.

October, 2024: A New Zealand vaping cessation guide and background evidence review has just been released (see “Further information” below for link)

Warn patients about the nicotine content in vapes. Cigarettes contain approximately 10 – 15 mg of nicotine on average, of which only 1 – 1.5 mg is absorbed.12 The maximum allowable limit of nicotine in vaping products in New Zealand (as of October, 2024) is 20 mg/ml for single use products and 28.5 mg/ml for reusable products.13 If a patient were to use a 20 mg/ml vape containing 2 ml of liquid, for example, this is equivalent to 40 mg of nicotine total; vaping this amount* has been reported as being equivalent to smoking approximately 20 cigarettes’ worth of nicotine (one pack).12 Therefore, depending on the nicotine concentration and daily liquid volume used, vaping can still result in significant nicotine intake, reinforcing or potentially worsening dependence. Nicotine delivered via vaping is more palatable than via smoking a cigarette, therefore it is likely that consumption will be higher. Clinicians should discuss these issues with patients before they start vaping and assist them in estimating the maximum amount of nicotine they should be vaping if they switch, based on their current level of smoking.

* The amount of nicotine absorbed by the body during vaping is dependent on the nicotine transfer efficiency. This has not been definitively established for vaping and potentially varies between devices. The referenced study used a transfer efficiency of 68% in calculations, e.g. if the total liquid nicotine content was 40 mg, 27.2 mg would be converted to aerosol and absorbed.12

Record vaping status. If a patient is identified as using vaping products or transitions to vaping, record this information in their clinical notes in addition to their smoking status:

| |

SNOMED CT term

|

SNOMED CT code

|

Read code

|

|

Current vaper

|

Currently vaping with nicotine

|

785889008

|

@MT0.09

|

| |

Currently vaping without nicotine

|

786063001

|

@MT0.10

|

| |

Currently vaping*

|

722499006

|

@MT0.11

|

|

Ex-vaper

|

Ex-vaping for less than 1 year

|

1137688001

|

@MT0.12

|

| |

Ex-vaping for more than 1 year

|

1137692008

|

@MT0.13

|

|

Trying to quit

|

Trying to give up vaping

|

1137691001

|

@MT0.14

|

|

Never vaped

|

Never vaped

|

1137690000

|

@MT0.15

|

* Ideally select a code that specifies whether or not nicotine is used. This non-specific code should only be used if the patient uses both nicotine-containing and nicotine-free vapes or is not certain whether nicotine is present in the type of vape they use.

Restrictions around access to vapes. Vaping regulations have progressively been introduced over time in New Zealand, and more are expected in the future. It is currently illegal to sell or supply vapes to anyone under the age of 18 years, and there is a limit on the nicotine content permitted in vapes (as noted previously). A future ban on disposable vapes is planned, among other restrictions such as reducing vaping signage and increasing fines for retailers breaching regulations (timeframe yet to be confirmed).

For further information on vaping for:

All patients who want to quit smoking should be offered pharmacological cessation support.6 Combination nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is the first line pharmacological intervention for smoking cessation and can also be used by patients who want to reduce the amount that they smoke.1 Bupropion and nortriptyline are fully funded smoking cessation medicines that have similar efficacy as NRT monotherapy.14 Varenicline is funded with Special Authority approval for patients who have been unsuccessful in quitting with other cessation medicines, but this has been unavailable for several years in New Zealand (see: “Varenicline is highly effective but currently unavailable in New Zealand”).1, 14

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is generally the first medicine(s) used

NRT works by providing some of the nicotine the patient is used to without the additional toxic substances; it is always safer than continuing smoking.1 NRT helps reduce cravings and other withdrawal symptoms that otherwise decrease the likelihood of a successful quit attempt if a patient were to completely and abruptly deprive themselves of nicotine.1 NRT also enables the patient to unlearn the perceived association between smoking and reward over several months, after withdrawal symptoms have abated.

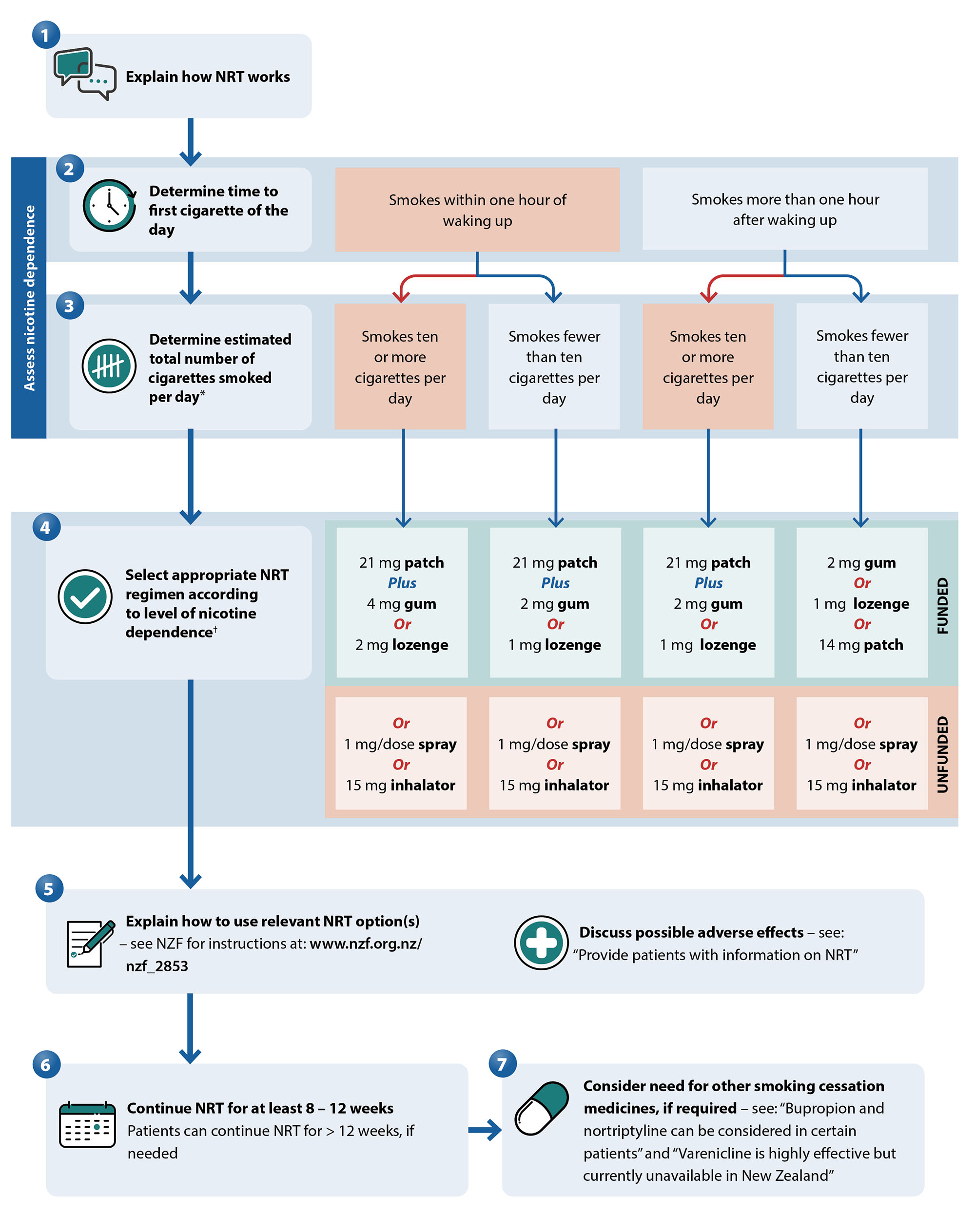

Select the appropriate NRT regimen according to the level of nicotine dependence

There are five different forms of NRT available on prescription or over the counter in New Zealand, indicated for adults and children aged 12 years and older: three funded options (patches, gum, lozenges) and two unfunded options (mouth spray and inhalators).6 When used correctly at an equivalent dose, all forms of NRT are similarly effective.

Funded NRT is available on PSO, meaning patients can be started immediately at the consultation (e.g. if there is concern they will delay going to the pharmacy).15 Pharmacists can also directly provide funded NRT in the absence of a prescription.15, 16 NRT is funded at a minimum of four weeks supply.15

Most patients trying to quit smoking do not use enough NRT and therefore have a higher risk of withdrawal symptoms and relapse to smoking; treatment with multiple forms (e.g. patches plus gum or lozenges) is advised in those with higher levels of nicotine dependence (see Figure 3 for specific recommendations and doses).1, 16 Combination NRT approximately doubles a patient’s chances of quitting smoking versus control (odds ratio = 1.93).14 This approach is suitable for patients who smoke within one hour of waking (most reliable indicator of dependence) and those who smoke ten or more cigarettes per day.1 Patches are often included in combination NRT as they make baseline adherence simple despite their slow nicotine release, which can be supplemented by faster acting NRT forms, such as gum or lozenges.6

Practice point: If a patient is not ready to completely stop smoking, NRT can also be used to help progressively reduce the amount they smoke prior to quitting.1

Figure 3. Algorithm for selecting and prescribing NRT. Adapted from Ministry of Health, 2021.1, 16

* If the paient thas recently reduced daily cigarette consumption, use their previous daily number of cigarettes smoked to guide selection of NRT16

† Lower patch strengths are generally not needed,16 however, they should be considered in patients weighing < 45 kg, e.g. 14 mg patch rather than 21 mg, even if the higher dose is indicated based on level of nicotine dependence1

Provide patients with information on NRT

When prescribing NRT, it is important to explain how it works (to promote adherence) and provide instruction on how prescribed forms should be taken (to ensure efficacy).

Additional considerations include:

Bupropion and nortriptyline can be considered in certain patients

Bupropion and nortriptyline are also medicines used to aid smoking cessation, and have comparable efficacy to NRT monotherapy.14 These options may be appropriate for patients who prefer quitting using a medicine that does not contain nicotine, or as alternatives if the patient has previously tried unsuccessfully to quit smoking with NRT. There is no evidence that combining NRT use with bupropion or nortriptyline has any additive benefit on smoking cessation rates.1

Bupropion

Bupropion is an atypical antidepressant that reduces smoking cravings and withdrawal symptoms.17 The exact mechanism of action is not certain, however, it likely weakly inhibits dopamine and noradrenaline reuptake in the brain and acts as a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist.17 These processes block the reward pathways associated with nicotine use and elevate mood in people experiencing nicotine withdrawal symptoms.17 Evidence from 71 RCTs (N = 14,759) suggests bupropion improves long-term smoking cessation rates by 43% versus control; approximately three additional patients quit per 100 who attempt to quit.14

Bupropion dosing recommendations for smoking cessation:15

- Step 1 – set a quit date

- Step 2 – initiate bupropion one to two weeks before this quit date, initially at a dose of 150 mg, once daily

- Step 3 – after three days, increase the dose to 150 mg, twice daily (minimum of eight hours between doses)*

- Step 4 – continue use of 150 mg, twice daily, for at least seven weeks in total (longer durations are acceptable, if needed, e.g. up to 12 weeks)

* The maximum daily dose is 150 mg in older frail patients, those with risk factors for seizures, or in patients with renal/hepatic dysfunction.

Combining bupropion and NRT is not thought to have an additive effect on cessation success.1 However, if this approach is trialled, regular monitoring of blood pressure is recommended.1

Bupropion is contraindicated in patients:15

- During acute alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal

- With a central nervous system tumour

- With a history of seizures, eating disorders (including bulimia or anorexia nervosa) or bipolar disorder; bupropion can delay weight gain (via appetite suppression), worsen depressive symptoms or prompt mood swings

- Who have used monoamine oxidase inhibitors within the last 14 days

Common adverse effects include insomnia, dry mouth, headache and nausea.17 Insomnia can potentially be addressed by taking the first dose early in the morning and the second in the late afternoon (at least four hours before bedtime), or by reducing total daily intake to 150 mg.17 Bupropion is not associated with significant weight increase after smoking cessation, so may be an appealing option in patients for whom this is a concern.17 Seizures occur in approximately one in 1,000 patients taking bupropion.17 Caution is advised when taking bupropion concomitantly with certain medicines that further elevate this risk, e.g. antipsychotics, antidepressants, antimalarials, tramadol, theophylline, systemic corticosteroids, quinolones and sedating antihistamines (see NZF interaction checker for further information).1, 15

Nortriptyline

Nortriptyline is a tricyclic antidepressant that reduces the severity of withdrawal symptoms.6 Evidence from 10 RCTs (N = 1,290) suggests nortriptyline improves long-term smoking cessation rates by 35% versus control; approximately two additional patients quit per 100 who attempt to quit.14

Nortriptyline dosing recommendations for smoking cessation:15, 17

- Step 1 – set a quit date

- Step 2 – initiate nortriptyline 10 – 28 days before this quit date, initially at a dose of 25 mg daily

- Step 3 – increase the dose gradually over ten days to five weeks to 75 – 100 mg

- Step 4 – continue use for three months in total (can be continued for up to six months, if required)

Doses should be slowly tapered when stopping nortriptyline to avoid withdrawal symptoms.15 Common adverse effects include dry mouth, drowsiness or sedation, light-headedness and constipation.1, 15 Nortriptyline must be used with caution in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease, as it can cause QT prolongation, sinus tachycardia and increases the risk of torsade de pointes.1, 15 ECG monitoring is advised in such cases.15 Nortriptyline is contraindicated in the immediate recovery period following myocardial infarction, in patients with pre-existing arrhythmias (particularly heart block), during manic episodes of bipolar disorder and within 14 days of monoamine oxidase inhibitor use.15

Varenicline is highly effective but currently unavailable in New Zealand

Varenicline is a nicotinic receptor partial antagonist, funded with Special Authority approval as a second line option for patients who have tried unsuccessfully to quit smoking after:

- At least two separate trials of NRT, with at least one of these attempts involving comprehensive advice on NRT use; or

- One trial of bupropion or nortriptyline

Other Special Authority approval criteria include that patients should be enrolled in (or about to enrol in) a smoking cessation programme which includes prescriber or nurse monitoring, must not have used varenicline in the previous six months, and that it is not being used in combination with other smoking cessation medicines. Varenicline is the most effective single formulation smoking cessation medicine, with data from 67 RCTs (N = 16,430) indicating patients are 2.3 times more likely to quit versus control.14

Supply issue: In April, 2021, the manufacturer of varenicline (Pfizer) advised there would be potential shortages due to impurity concerns. A decision was then made to pause global distribution and as of July, 2024, all strengths of varenicline are out of stock in New Zealand. It is estimated that product may be available in New Zealand by the end of March, 2025. Therefore, while it is currently unavailable, it is important clinicians are aware varenicline will likely become an option again in the future; this may be particularly relevant for supporting patients who have otherwise unsuccessfully attempted to quit using other pharmacological options in its absence.

For further information, see: pharmac.govt.nz/medicine-funding-and-supply/medicine-notices/varenicline.

Initiating varenicline treatment

Varenicline is funded for 12 weeks of treatment.15 Patients usually begin one to two weeks before their quit date, with a one week dose escalation period, followed by 11 weeks of maintenance treatment:* 15

- Step 1 – set a quit date

- Step 2 – initiate varenicline one to two weeks before this quit date, initially at a dose of 500 micrograms, once daily, for the first three days

- Step 3 – increase the dose to 500 micrograms, twice daily, for four days

- Step 4 – increase the dose to 1 mg, twice daily

- Step 5 – most patients should continue with this maintenance dose for 11 weeks. However, if not tolerated, reduce to 500 micrograms, twice daily.

* Patients with an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73m2 should be prescribed an initial dose of varenicline 500 micrograms, once daily, increased after three days to 1 mg, once daily.

Extended durations of varenicline treatment (e.g. 24 weeks total) are unlikely to provide any additional benefit on average,19 and would not be funded under the Special Authority criteria.

Prepare patients for potential adverse effects

To help patients taking varenicline complete the full treatment course, they should be prepared for the possibility of adverse effects before initiation. Varenicline is initiated at a low dose, and increased slowly to reduce the likelihood of adverse effects. Encourage patients to discuss any adverse effects rather than stopping the medicine, as in many cases they can be managed.

- Nausea is the most common adverse effect associated with varenicline treatment, occurring in up to 30% of patients.1 However, nausea is usually mild, and rarely results in discontinuation. Nausea may be reduced by taking varenicline with easily digestible carbohydrates (e.g. bananas or white rice) or water, or reducing the dose (e.g. to 500 micrograms, twice daily).1 An antiemetic (e.g. prochlorperazine or metoclopramide) may be appropriate for patients experiencing moderate to severe nausea.

- Insomnia, abnormal dreams and headaches may occur with varenicline treatment and are a common cause of discontinuation.1 However, patients should be reassured that symptoms are usually only transient and are generally outweighed by the long-term benefits of smoking cessation. If sleep disturbance is ongoing and cannot be tolerated, consider progressively reducing the evening dose until it is stopped, maintaining the morning dose only.17

- Serious adverse psychological effects are rare. Early post-marketing reports into varenicline safety indicated a possible association with mood changes, depression and suicidal ideation.17 However, subsequent meta-analyses have not established a causal link, with rates of reported serious adverse effects in RCTs being similar between varenicline, NRT and placebo.14 Patients taking varenicline should be advised to stop treatment and contact a health professional if they notice negative changes in behaviour or thinking, mood swings, anxiety, depression or suicidal ideation.

Remind the patient to be mindful of alcohol intake

Varenicline is associated with decreased tolerance to alcohol, unusual or aggressive behaviour when drinking and memory loss.15 Advise patients to reduce or avoid alcohol consumption until they know how varenicline affects them.

There is conflicting data on the usefulness of combining varenicline with NRT

Varenicline is not funded when co-prescribed with NRT. The most recent evidence indicates that there is no benefit of this combination. A 2021 RCT (N = 1,251) found no difference in smoking cessation rates at 52 weeks with 12-week combination varenicline plus NRT treatment versus 12-week varenicline monotherapy (or among those treated for 24 weeks).19

Follow up is important to maximise success of quit attempts.1, 6 An appointment (or phone call) should ideally be scheduled a week after the “quit date” to check progress, and to discuss adherence and adverse effects associated with smoking cessation medicines.1 Ministry of Health guidelines recommend at least four follow up contacts to effectively deliver behavioural support.6

Adjusting the doses of medicines

Smoking tobacco causes exposure to particulates that induce enzymes involved in the metabolism of certain medicines, such as clozapine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and warfarin.6 Therefore, when people taking these medicines quit smoking, the dose may need to be reduced initially, and follow up monitoring is required. For example, a strategy in patients taking clozapine is to initially reduce the dose over one week (e.g. by 25%) when quitting smoking;20 monitor patient response and consider further dose adjustments over the next four weeks based on adverse effects, if required.15

The New Zealand Formulary (NZF) interaction checker can be used to assess whether a patient’s current medicines have potential interactions with tobacco and nicotine. For further information, see: nzf.org.nz.

Addressing relapses

Relapses (returning to a regular smoking pattern) are most common in the first days and weeks following cessation (mostly due to the effects of nicotine withdrawal).1 As such, it is essential behavioural support is delivered promptly, and patients are encouraged in their progress and self-efficacy, i.e. their belief in their ability to quit smoking. Patients who relapse usually have inadequate behavioural support as part of their cessation plan, experience strong withdrawal symptoms (particularly if they do not receive smoking cessation medicines) or have inadequate follow up after the initial delivery of support.1

If a patient reports to the primary care team that they have relapsed, it is important to focus their attention on the length of time they were able to stay smokefree and explain that a single relapse does not equate to a complete failure. The reasons for the lapse can be discussed as a learning opportunity and framed as a positive, e.g. “we have now identified a trigger for smoking and this is our strategy for avoiding or overcoming it in the future”. Pharmacological treatment (i.e. with NRT or other medicines) is also important to reduce the risk of future relapses. If the patient is already using medicines to support smoking cessation, a pragmatic approach could be:

- If only a few days (to a week) has passed since they relapsed, it may be appropriate to continue with the remaining weeks of the treatment course

- If the relapse is longer (several weeks or more), or the patient is considered high risk for future relapses, restarting the treatment course from the beginning might be more beneficial to support the quit attempt (assuming the duration of treatment has not already been extended previously). Longer overall treatment durations could also be considered in this scenario, particularly with NRT.

The importance of overcoming a deadly habit: the harms caused by smoking and progress towards smokefree goals

The scope of adverse health outcomes linked to smoking is considerable, including most major cardiovascular and respiratory conditions, numerous types of cancer and many other conditions (Table 2).21 In general, a dose-response relationship exists between the amount and duration of smoking and the risk of adverse health outcomes.21 However, there is no “safe level” of use.

Smoking is the leading cause of preventable death in New Zealand, and is associated with approximately 4,500 deaths each year (350 of which involve second-hand smoke exposure).6

Table 2. Estimated risks associated with current smoking status for selected health outcomes. Adapted from Dai et al, 2022.21

| |

|

Mean relative risk versus non-smokers at different levels of exposure* |

Average %

increase in risk of health outcome (star rating)† |

|

Health outcome

|

Risk unit

|

5

|

10

|

20

|

40

|

|

Laryngeal cancer

|

Pack-years**

|

2.3

|

3.8

|

7.2

|

14.6

|

375%

|

|

Aortic aneurysm

(ref age: 55–59 years)

|

Cigarettes/day |

2.5

|

3.8

|

5.4

|

6.2

|

150%

|

|

Peripheral artery disease

(ref age: 60–64 years)

|

2.5

|

3.8

|

5.7

|

7.8

|

137%

|

|

Lung cancer

|

Pack-years |

1.6

|

2.5

|

5.11

|

11.6

|

107%

|

|

Pharyngeal cancer

|

1.7

|

2.2

|

3.0

|

3.9

|

92%

|

|

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

|

1.6

|

2.2

|

3.2

|

5.1

|

72%

|

|

Lower respiratory tract infection

|

Cigarettes/day

|

1.5

|

1.8

|

2.6

|

3.0

|

55%

|

|

Oesophageal cancer

|

Pack-years

|

1.2

|

1.5

|

2.0

|

3.1

|

29%

|

|

Rheumatoid arthritis

|

Cigarettes/day |

1.2

|

1.4

|

1.7

|

1.7

|

23%

|

|

Ischaemic heart disease

(ref age: 55–59 years)

|

1.7

|

2.1

|

2.4

|

4.2

|

20%

|

|

Macular degeneration

|

1.3

|

1.7

|

2.2

|

2.4

|

19%

|

|

Stroke

(ref age: 55–59 years)

|

1.4

|

1.8

|

2.2

|

2.4

|

17%

|

|

Type 2 diabetes

|

1.2

|

1.4

|

1.5

|

1.7

|

16%

|

|

Alzheimer’s and other dementia

|

1.2

|

1.3

|

1.5

|

1.7

|

10%

|

|

Atrial fibrillation and flutter

(ref age: 55–59 years)

|

1.3

|

1.4

|

1.4

|

1.4

|

6%

|

|

Lip and oral cavity cancer

|

Pack-years

|

1.2

|

1.4

|

2.1

|

3.5

|

5%

|

* See Dai et al, 2022 21 for the 95% uncertainty intervals associated with each mean risk value and for a more comprehensive list of health outcomes

† Based on a highly conservative interpretation of evidence that accounts for heterogeneity between studies and other forms of uncertainty (i.e. the likely minimum effect); the true average increased risk associated with current smoking status may be higher. Star rating indicates the magnitude of effect and strength of evidence (a one-star rating would suggest no association; higher ratings indicate larger effects and/or stronger evidence). For further information on this rating system, see: www.nature.com/articles/s41591-022-01973-2.

** Calculated by multiplying the number of packs of cigarettes smoked per day by the number of years the person has smoked. For example, five pack years could mean a person smoked one pack of cigarettes per day for five years, half a pack per day for ten years, or two packs per day for two and a half years, etc.

Smoking rates have declined in New Zealand, but we can still do better

In 2011, the New Zealand Government set a target that smoking rates across all population groups would be less than 5% by 2025.6 Initiatives to support this objective include:7

- Warning labels on cigarette packets

- Banning tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship

- Smoke-free public health policies and legislation

- Higher prices and taxes on tobacco products

- Improving the access and availability of smoking cessation services

- Liaising with international partners to reduce cigarette smuggling and cross-border advertising

Since then, national smoking rates have progressively declined. In 2022/23, approximately 7% of people reported being daily smokers, down from 9% in 2021/22, and 16% in 2011/12.22 Decreases have been observed across all ethnic groups over time, however, inequity still persists.22 As of 2022/23, daily smoking rates were still higher among Māori (17%) compared with people of Asian (8%), Pacific (6%)* or European (6%) ethnicity.22 Smoking also continues to be significantly more prevalent among adults living in the most deprived communities (11%) compared with those in the least deprived communities (3%).22 One in six people who previously smoked reported quitting in the 12 months prior to the 2022/23 New Zealand Health Survey (similar to previous years).22

As smoking prevalence has decreased in New Zealand, rates of vaping have progressively increased.22 As of 2022/23, one in ten adults report vaping daily, with most use occurring among young adults aged 18 – 24 years (25%), Māori (24%) and Pacific Peoples (19%), and those living in the most deprived communities (16%).22 For further discussion, see: “What about vaping as an alternative to smoking?”.

* Daily smoking rates reported for Pacific peoples in 2022/23 were approximately one third the levels reported for 2021/22 (18%).22 However, further investigation is needed to confirm the accuracy of this finding, which may be influenced by factors such as sample size and data collection.

-

Second-hand smoke exposure remains a concern

Second-hand smoke exposure is a significant cause of illness and premature death, increasing the risk of conditions such as ischaemic heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and lung cancer. For children, exposure to second-hand smoke can lead to low birth-weight, sudden unexpected death in infancy, asthma, otitis media and lower respiratory infections.23, 24 Despite a declining prevalence over time, 3.2% of adults and children in New Zealand are exposed to second-hand smoke, with people aged 15 – 24 years, Māori children, and Pacific non-smoking adults having the highest risk of exposure.24

-

How are we performing in the global context?

A 2023 report from the World Health Organization (WHO) identified New Zealand as performing at a high level across multiple anti-tobacco/smoke-free measures.25 Among countries in the Western Pacific Region (including Australia), New Zealand had the lowest rates of daily adult smokers.25