Published: 18th October 2024

Smoking rates are progressively declining in New Zealand; daily smoking among all adults was 16% in 2011/12, 9% in 2021/22 and most recently, 7% in 2022/23.1 However, smoking is analogous to a chronic disease with frequent relapses, and ongoing work is required to continue this downward trend in the number of people who smoke.

Smoking rates are substantially higher than the national average, and particularly concerning in:

- People who live in highly deprived areas

- Māori and Pacific peoples

- People with mental health disorders

The good news is that many people who smoke also frequently think about quitting, regardless of their background. A New Zealand survey demonstrated that four out of five people aged 18 – 28 years who smoke reported making at least one quit attempt (that lasted 24 hours or longer) in the previous 12 months.2 However, most attempts to quit do not succeed, and long-term success, e.g. remaining smokefree for at least six months, is only achieved in 5% of attempts without the support of a health professional.3

There are two strategies that health professionals can pursue in order to increase the number of people who quit smoking long-term:

- Increase the number of people who attempt to quit smoking

- Increase the success rate of quit attempts

Brief advice to stop smoking and, most importantly, an offer of cessation support by a health professional can increase the number of people who attempt to stop smoking by 40 – 60%.4 This means that one extra person can be expected to attempt to give up smoking for every seven people who are advised to do so and offered support in their attempt.4

Tailoring support to patients by understanding their quit-history and circumstances means that health professionals can increase the chances of the patient’s next attempt succeeding. It is important to let patients who are quitting know that many people who attempt to quit will relapse. However, behavioural support, e.g. Quitline, and pharmacological smoking cessation aids, do help prevent a lapse in abstinence becoming a return to regular smoking.

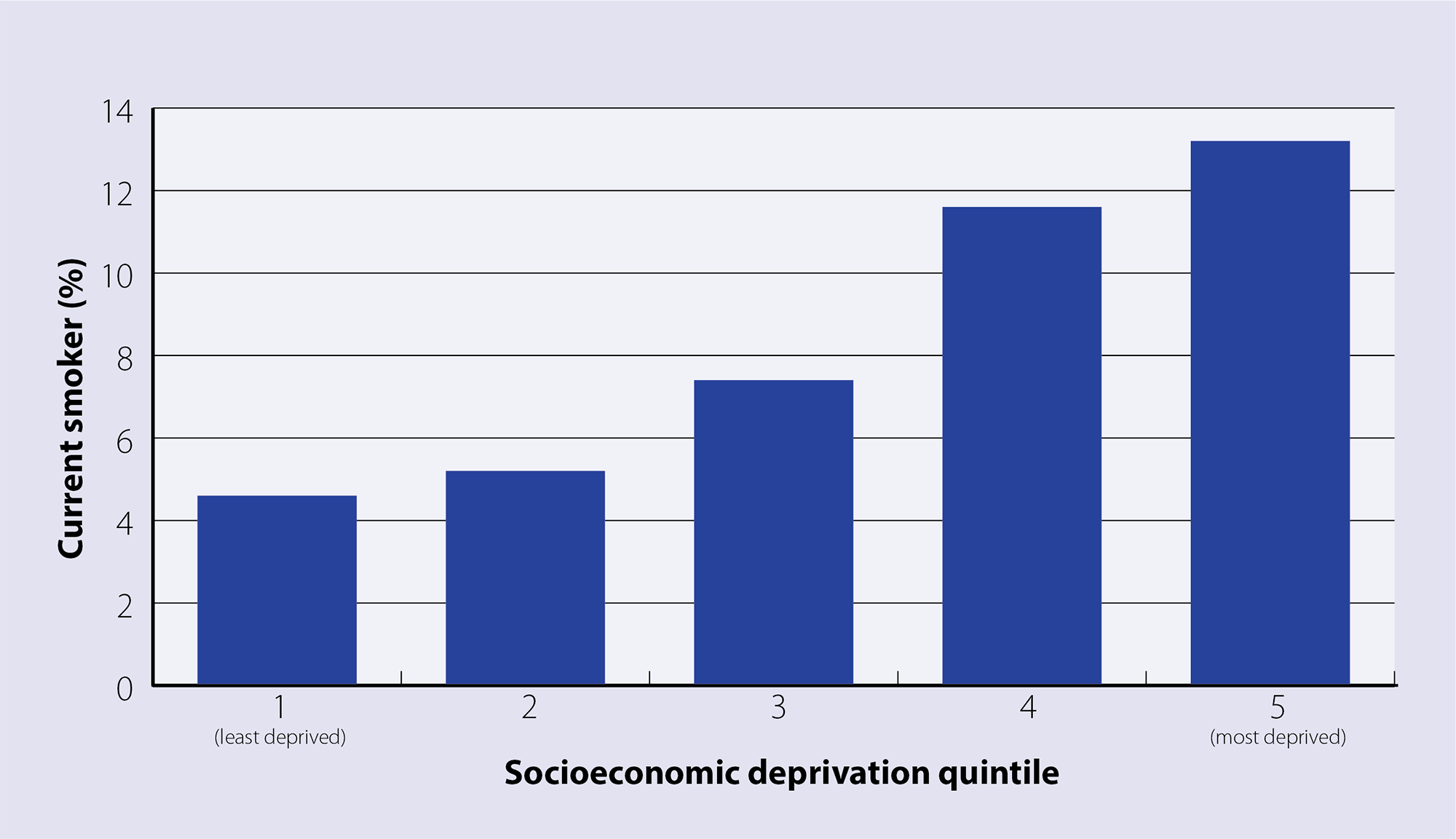

Current smoking is associated with poverty

Socioeconomic deprivation is strongly associated with smoking in New Zealand (Figure 1). After adjusting for age, sex and ethnicity, a person from one of the most deprived communities in New Zealand (Quintile 5) is three times more likely to be a current smoker, compared with a person from one of the least deprived communities (Quintile 1).1 People living in the most deprived Quintile are also significantly more likely to smoke during pregnancy (19.5%) compared with those in the least deprived quintiles (3.3%).5

Figure 1. Percentage of people in New Zealand who are current smokers by deprivation status in 2022/23.1

Smoking rates in Māori and Pacific peoples must be reduced further

One-fifth (20.2%) of Māori are current smokers and 17.1% are daily smokers, rates that are approximately three times higher than in people of European ethnicity.1 More than one-third of Māori females have been reported to smoke during pregnancy.6 Death rates due to lung cancer are three times higher in Māori than non-Māori.7 However, an increasing proportion of Māori who smoke are successfully quitting.

In 2011/12, an estimated 8% of Māori who previously smoked had successfully quit within the past 12 months; ten years later, this figure had increased to almost 20%.1 Even in patients who do not successfully quit, it is important that unsuccessful attempts are acknowledged, and information gained is applied to future attempts to quit smoking. The proportion of Māori youth who are daily smokers is also decreasing, from over 25% of Year 10 students in 2001 to 3.4% in 2021.8 The amount of Māori students who had never smoked increased from approximately 20% to almost 90% over the same period. However, as smoking prevalence has decreased, rates of vaping have progressively increased.1 As of 2022/23, 10% of adults report vaping daily, with most use occurring among young adults aged 18 – 24 years (25%) and Māori (24%).1

Māori who do not smoke are exposed to second-hand smoke more (9.2%) than non-Māori (3.6%).9 Overall, Māori are almost three times more likely to die from conditions related to second-hand smoke exposure than non-Māori, and experience five times the level of associated health loss.9 Children are more sensitive to the effects of second-hand smoke than adults, meaning the associated burden of disease in Māori children is of particular concern.

Pacific peoples also have had higher rates of smoking than the general population, but the prevalence is declining. In the 2022/23 Health Survey, overall rates of daily smoking among Pacific peoples were approximately one-third the level reported the year before (6% versus 18% in 2021/22). However, further investigation is needed to confirm the accuracy of this finding as it is a much more significant decrease than anticipated, and findings may be influenced by factors such as sample size and data collection methods. Rates may also vary depending on the predominant sub-ethnicity surveyed, e.g. Tokelauan, Cook Islander, Fijian, Samoan, Niuean. Despite the rate of regular smoking among Pacific Year 10 students declining over time, it remains higher (6 – 11%) than students of non-Pacific/non-Māori ethnicity (3%).8 Continued efforts are required to further mitigate tobacco use and associated harm among Pacific communities.

Smoking prevalence increases with severity of mental health disorders

People with a mental health disorder are approximately twice as likely to smoke as people who do not have a mental health disorder and generally, the level of nicotine dependence increases with the severity of the illness.10 Many people with mental health disorders who smoke will require additional support from health professionals to achieve long-term abstinence.10, 11

General practitioners are encouraged to Ask about smoking, Briefly advise to quit and offer Cessation support (ABC), to all patients who smoke, at every consultation.11 Some health professionals may be reluctant to persistently advise people to quit smoking due to concerns that their relationship with patients may be damaged. However, it should be remembered that many people who smoke are open to the idea of quitting, and most wish they had never started.11, 12

Practice point: “When was the last time you smoked a cigarette?” is a non-judgemental way of enquiring about smoking status in patients who are known to be smokers.

Understand the barriers before you start

Understanding why the patient has not made a quit attempt yet, their barriers to quitting smoking, and reasons for relapse if they have tried to quit before, allows health professionals to provide individual strategies. For example, if the patient’s partner is influencing their smoking habits, encouraging the partner to join the quit attempt may increase the chances of success.13

Fear of consequences can encourage smoking

For people whose social life is restricted to family/whānau and neighbours, a fear that quitting smoking can result in being “left-out” socially is a barrier to quitting.12 Concerns that giving up smoking will cause illness are also not uncommon, e.g. coughing or chest infections following quitting. Other barriers to quitting smoking that are frequently reported include: fear of weight gain, boredom and the timing of a quit attempt being problematic.12 A patient’s individual concerns about quitting need to be addressed when discussing smoking cessation.

Viewing smoking as a stress-reliever can be a barrier to quitting

People who smoke often view it as a stress-relieving activity, therefore do not want to quit.12, 14 There may also be concern that quitting smoking will worsen mood in people with a mental health disorder.14 In fact the opposite is more likely to be the case: smoking cessation has been shown to have beneficial effects on mood disorders, with an effect size at least equal to treatment with antidepressants.14 Health professionals should acknowledge that a patient’s mood may improve in the minutes after smoking a cigarette. However, this is an opportunity to explain to the patient that the reason they feel better is because they are addicted to nicotine, and that every puff continues this cycle (see: “Why does quitting smoking improve mental health?”). The patient can then be reassured that all people who break the cycle of smoking addiction will experience mental health benefits.14 N.B. The doses of antipsychotics used to treat some mental health disorders (and insulin) may need to be adjusted if abrupt cessation occurs in a person who is heavily dependent on cigarettes (see: “Medicine doses may need adjustment for some people who quit”).

Why does quitting smoking improve mental health

A meta-analysis of 102 studies found consistent evidence that smoking cessation is associated with improvements in depression, anxiety, stress, quality of life and positive affect.14 This benefit was similar for people in the general population and for those with mental health disorders.14

The fallacy that smoking improves mental health can be understood when the neural changes that long-term smoking causes are considered. Over time, smoking results in modification to cholinergic pathways in the brain, resulting in the onset of depressed mood, agitation and anxiety during short-term abstinence from tobacco, as levels of nicotine in the blood drop.14 When a person who has been smoking long-term has another cigarette their depressed mood, agitation and anxiety is relieved. However, as a person continues to abstain from smoking the cholinergic pathways in the brain remodel and the nicotine withdrawal symptoms of depressed mood, agitation and anxiety are reduced through abstinence from nicotine. The process whereby people relieve withdrawal symptoms with a drug, i.e. nicotine, which then reinforces these symptoms is referred to as a withdrawal cycle and it may also be associated with a decline in mental health.14

Medicine doses may need adjustment for some people who quit

Hydrocarbons and tar-like products in tobacco smoke are known to induce cytochrome P450 enzymes, particularly CYP1A2.15 When people taking medicines that are metabolised by this enzyme stop smoking there may be an initial rise in medicine levels in their blood as enzymatic activity falls to normal levels. N.B. Nicotine does not have the same effect on cytochrome P450 enzymes as tobacco does.

There may be some instances where stopping smoking in a patient taking certain antipsychotics (e.g. clozapine, olanzapine, chlorpromazine, haloperidol) or insulin causes clinically significant changes in serum concentrations and doses may need to be adjusted.15 Smoking cessation can result in transient worsening of glycaemic control in patients with diabetes (nicotine exposure influences insulin sensitivity), meaning that increased blood glucose monitoring may be required initially.16

The New Zealand Formulary (NZF) interaction checker can be used to assess whether a patient’s current medicines have potential interactions with tobacco and nicotine. Ensure potential interactions for both components are searched (i.e. the medicine plus tobacco and nicotine). For further information, see: nzf.org.nz.

From talking to quitting

Motivational interviewing can increase the likelihood that a patient will attempt to quit smoking and increase the chances of them succeeding.10

The general techniques of motivational interviewing include:10

- Expressing empathy

e.g. “So, you’ve already tried to give up smoking a couple of times and now you’re wondering if you will ever be able to do it? I understand that it is a significant lifestyle change to make.”

- Developing the discrepancy between the goal of being smokefree and the behaviour of smoking

e.g. “It’s great that your health is important to you, but how does smoking fit in with that for you?”

- Rolling with resistance

e.g. “It can be hard to cope when you’re worried about your mother’s health and I realise that smoking is one of the ways that you’ve used to give yourself a break. What other ways do you think you could use?”

- Encouraging self-efficacy

e.g. “Last time you didn’t think you’d be able to manage without smoking at all – and you’ve actually gone all week with only two cigarettes – what did you do differently this time to make that happen?”

A goal of care when consulting with patients who are current smokers is to negotiate a firm quit date and to agree on “not one puff” from that point onwards.10

Cessation support is the most important aspect of the ABC approach

It is important that cessation support, e.g. referral to smoking cessation service, should be offered to all people who smoke, regardless of their readiness to stop smoking.11 Only offering cessation support to people with a stated desire to quit smoking is a missed opportunity for positive change.

A meta-analysis of the effect of cessation support found that offers of cessation support by health professionals, e.g. “If you would like to quit smoking I can help you do it”, motivated an additional 40 – 60% of patients to stop smoking within six months of the consultation, compared to being advised to quit smoking on medical grounds alone.4 It is important to note that the motivation of patients to stop smoking was not assessed before offers of cessation support were made.

Referral to a smoking cessation service is recommended

Quitline is a nationwide smoking cessation service that offers telephone, text and online support, 24 hours per day, seven days per week, to all people who want to quit smoking. Quitline advisors can help people establish a tailored plan to quit smoking and assist them in accessing nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). People can choose to receive regular ongoing supportive texts from Quitline in either Te Reo Māori or English.

People can self-refer to Quitline by:

Health professionals can also refer patients to Quitline, either directly via the PMS or by emailing a Quitline referral form (https://quit.org.nz/helping-others-quit#primary-care---phos) to referrals@quit.org.nz.

For further information go to: www.quit.org.nz

There are dedicated Kaupapa Māori and Pacific stop smoking services available across the country. Visit the interactive map at www.smokefree.org.nz/help-advice/stop-smoking-services to search for options based on region, or call Quitline directly to discuss what help is available locally. For example, Toki Rau is a stop smoking service with eight locations in Northland, which offers face-to-face support in an individual, whānau/family or group setting, and helps people access NRT. In Auckland/Waitematā, The Fono offers a stop smoking service with a focus on improving wellbeing and equity for Pasifika communities.

Strategies to achieve a smokefree pregnancy

All pregnant patients who smoke should be advised to stop and offered help accessing smoking cessation services.11 Behavioural interventions should be prioritised first-line (e.g. group sessions), however, NRT can be used during pregnancy and breastfeeding if quit attempts are unsuccessful; this should involve a shared decision-making conversation in which the risks and benefits of NRT are discussed.10, 11, 17 The small amount of studies available relating to NRT use during pregnancy means that no definitive conclusions about safety can be made, and intrauterine nicotine exposure is possible. However, any potential harms to the fetus from maternal NRT use would be significantly less than if the patient kept smoking.11, 17

Incentive programmes have been launched in some regions to encourage and support pregnant people to quit smoking. For example, as part of the Te Hā – Waitaha (Canterbury) stop smoking services, a $50 voucher is given to all pregnant people who attend an initial session, with further vouchers given if they remain smokefree at 4 weeks, 12 weeks and at the time of birth. In addition, they also offer a kaupapa Māori programme called He Mokopuna nā Hinerauāmoa, which is “designed to support wāhine Māori to reclaim their hā (breath) and become smoke-free during pregnancy”. This programme offers additional financial incentives for pregnant wāhine Māori, as well as access to small group sessions where they are “provided a safe space to explore mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) while receiving personalised smoke-free support”. Other incentive programmes exist elsewhere in the country (e.g. Waikato), and may vary in terms of eligibility criteria, timing and value of incentives and outcomes measured. For further information, patients can discuss options with a Quitline advisor.

Preventing smoking relapses

Health professionals can discuss strategies with patients to help manage triggers where there is extra pressure to smoke. For example, focus on something that is important to the patient and incorporate it into a response that they use to decline an offer to smoke, e.g. “No thanks, my daughter has asthma – our home is now smokefree to help her breathing get better”.

Creating a wave of social support

Encourage the person quitting to reach out for assistance from anyone they know who has previously quit smoking. Peer support for people who are attempting to quit smoking can take many forms. The rationale is that a person with similar life experiences to the person who wants to stop smoking can provide practical tips that fit with their lifestyle. A friend or family member is also more likely to have regular contact with the person attempting to quit. Examples of peer support might be having a coffee or tea together each morning to discuss any difficulties or temptations, or attending situations together where there may be a strong temptation to smoke, e.g. the pub. Many maraes and community groups in New Zealand provide support for people attempting to quit smoking or trying to remain smokefree.

There is some evidence that peer support may be more successful when people in deprived communities attempt to quit smoking, compared with people in the general population.17

The Quitline Community Blog is the most popular online smoking cessation peer support forum operating in New Zealand. People who are attempting to quit smoking can be encouraged to access this forum to receive support at any time of the day or night.

For access, visit:

Children are a positive and motivating influence

The health-related and financial benefits that the children of people who smoke gain when their parents quit smoking is a powerful motivating factor.12 In particular, prospective parenthood can provide additional motivation to stop smoking. Having a partner who continues to smoke during pregnancy is highly predictive of a return to smoking among patients who are pregnant.13 Having a smokefree pregnancy, and maintaining a smokefree household, means that children are less likely to develop middle ear infections, lower respiratory illness, asthma or abnormal lung growth, and have a lower incidence of sudden unexplained death in infancy.10

Quitting smoking to improve a pet’s health may also be a motivating factor for some people; smoking around pets has been reported to increase their risk of cancer two-fold.

The cost of smoking just keeps going up

Cost increase is a recognised method for decreasing cigarette consumption. As part of the drive to reduce smoking rates to < 5% in New Zealand by 2025, successive governments have progressively increased the prices and taxes on cigarettes and loose tobacco.

At an average cost of $38/pack, a pack-a-day smoker would be spending $266 a week on cigarettes, or more than $13,800 per year. If the person quits, they would save more than $55,000 after four years.

The money that a family/whānau can save by quitting smoking could be used to create goals that unite families in their desire to be smokefree. For example, as well as spending the extra money on essentials such as clothing, a small weekly treat such as going to the local swimming pool can provide an ongoing and tangible incentive to being smokefree. Longer term goals such as saving for a family holiday can also create family “buy-in” and may help parents remain abstinent from smoking in the months following their quit date.

An online calculator can be used by people to assess the savings that could be made if they quit smoking.

If a patient who is attempting to quit reports that they have had a brief smoking lapse, it is important that they do not see this as a failure. Support is required to help them avoid feelings of guilt and loss of control that can undermine their quit attempt. Remind patients that many people who quit experience lapses. Encourage the patient to continue to use NRT and any other smoking cessation medicines that have been prescribed. Ask the patient to again commit to “not one puff” onwards and to ensure that cigarettes, lighters and ashtrays have been discarded.