In BPJ 24 (Nov, 2009) we reported that oxycodone use in New Zealand

had been steadily rising. Latest pharmaceutical dispensing data suggest that oxycodone prescriptions are still rapidly

increasing, and now exceed morphine, which is the preferred first-line option for severe pain (Figure 1). This is a serious

concern given the significant problems with oxycodone misuse now being experienced in other countries.

Oxycodone is often commenced in secondary care and continued once patients are discharged. Prescribers must ensure that

oxycodone use is appropriate and justified and that they are not inadvertently worsening misuse and addiction problems

in the community.

Oxycodone is a strong opioid for severe pain

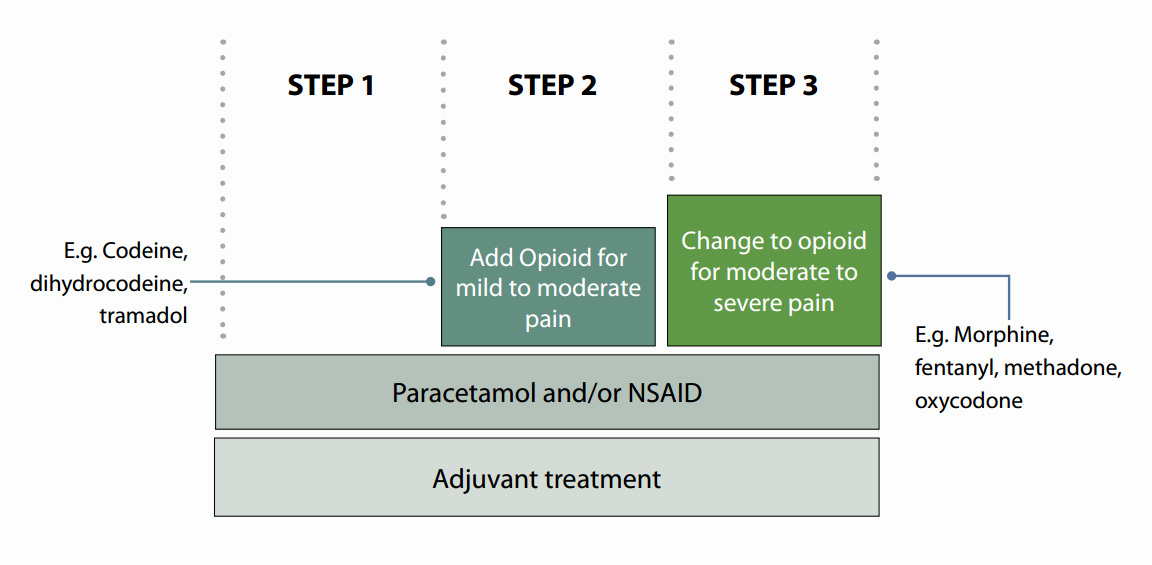

From its name, oxycodone is often perceived as being similar to codeine, an opioid for mild to moderate pain, but in

fact oxycodone is an opioid for severe pain, like morphine. Strong opioids are positioned at step three on the WHO analgesic

ladder (Figure 2) and they are indicated in moderate to severe pain.

Figure 2: WHO analgesic ladder

Use oxycodone only when morphine is not tolerated

If a patient requires a medicine at step three on the analgesic ladder, morphine is the first-line treatment. Oxycodone

has no better analgesic efficacy than morphine but is significantly more expensive. Total expenditure on oxycodone increased

by more than $1 million in 2010 (from $4,043,812 in 2009 to $5,167,500 in 2010). Morphine

expenditure remained fairly stable increasing from $3,075,217 in 2009 to $3,235,862 in 2010.*

Oxycodone should only be considered for moderate to severe pain if morphine is not tolerated or not suitable. Like morphine,

oxycodone has active metabolites that accumulate in renal impairment. It should therefore be used with caution in patients

with renal impairment, or a renal safer opioid such as fentanyl or methadone should be considered instead.1

Fentanyl patches can be considered for people with moderate to severe chronic pain and stable opioid requirements, who

experience intolerable adverse effects to morphine, or are unable to take oral medication. Care must be taken in selecting

the appropriate dose when converting from oral opioids. Seek advice if uncertain.

Methadone (oral tablets) can be considered for people with severe, complex pain that is uncontrolled with morphine,

or if adverse effects experienced with morphine are intolerable. Again, care must be taken when selecting an appropriate

dose and monitoring is required due to the long half-life and tendency for drug accumulation. Ask for advice if unfamiliar

with its use.

For more information see; “Pharmacological

management of chronic pain” BPJ 16 ( Sep, 2008) and “Methadone

- safe and effective use for chronic pain” BPJ 18 (Dec 2008).

For more information see; “Pharmacological

management of chronic pain” BPJ 16 ( Sep, 2008) and “Methadone

- safe and effective use for chronic pain” BPJ 18 (Dec 2008).

Increased fracture risk in elderly people

All opioids affect the central nervous system. This can be a significant issue in elderly people, especially if they

are dehydrated, have significant co-morbidities or renal impairment. Careful dose titration is required to avoid adverse

effects such as hallucinations, confusion and other cognitive impairment, which contributes to the risk of falls and subsequent

injury. Oxycodone, morphine and fentanyl have all been associated with increased risk of fracture in elderly people.1

No consensus on role in chronic pain management

The role of oxycodone, along with other strong opioids, in the treatment of chronic, non-malignant pain is controversial.

Long-term use of opioids is associated with adverse effects such as addiction, tolerance and hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity

to pain).2 Long-term use of opioids, especially higher doses, is also associated with immunosuppression, although

the mechanism for this is not fully understood and may be related to the pain condition itself.1

A recent systematic review concluded that the adverse effects associated with the long-term use of opioids in osteoarthritis

outweighs the benefit.3 While another review found little evidence for the use of opioids for chronic back

pain.4 The benefit for neuropathic pain has only been demonstrated in the short term.2

There is evidence that the long-term use of high doses of opioids (equivalent to 200 mg morphine) in patients with non-malignant

pain is strongly associated with an increased risk of death.5 Other contributing factors include concurrent

use of benzodiazepines, more than one opioid and alcohol.5

Use of opioids for long-term non-malignant pain should only be considered if other treatment or analgesia options are

not suitable or have not controlled pain adequately. The difficulty is in selecting an appropriate alternative medicine

for long-term pain if an opioid is not used. Non-opioid pain relief for moderate to severe pain may include; antidepressants,

anticonvulsants, antiarrythmics, steroids or muscle relaxants.

Patients who are prescribed opioids for long periods, especially if the dose is escalating and the pain is worsening,

should be regularly assessed (for a different diagnosis or worsening of the condition) or referred to a specialist pain

clinic.

Best Practice Tip: Consider the psychosocial factors that may influence

the nature and intensity of pain, especially chronic pain. Experience of pain can induce or exacerbate depression and

anxiety, influence social interaction, prevent work and impair relationships. Ensure these aspects of pain are acknowledged

and appropriately managed where possible.

Best Practice Tip: Consider the psychosocial factors that may influence

the nature and intensity of pain, especially chronic pain. Experience of pain can induce or exacerbate depression and

anxiety, influence social interaction, prevent work and impair relationships. Ensure these aspects of pain are acknowledged

and appropriately managed where possible.

Potential for misuse and addiction

Oxycodone has become one of the most problematic misused opioids in the United States.6 In Canada there has

also been a significant rise in the number of people seeking treatment for oxycodone addiction.7 In New Zealand,

there is anecdotal evidence of an increase in prescription medicine dependence,8 however, it is unknown to

what extent oxycodone is implicated.

The potential for addiction and misuse of oxycodone is comparable to morphine.9 However, it is unlikely for

a person with no previous history of addictive or risk-taking behaviour to develop an addiction or misuse problem when

using opioids. One study found that approximately 3% of people who take opioids for chronic non-cancer pain develop misuse

or addiction problems and 11% develop “aberrant drug-related behaviours” such as aggressively requesting medicines,

self-directed dose escalation or inappropriate use of the medicine, e.g. injecting. However, when removing people with

a history of drug misuse or addiction, these numbers reduce to 0.2% and 0.6% respectively.10

In susceptible people, physical and psychological dependence to opioids can develop within a relatively short period

of continuous use (two to ten days).15

Prescribers should be alert for signs of addiction or misuse including:

- Escalating dose requirements

- Refusal to try alternative non-opioid analgesia or other pain treatments

- Early refills

- Frequent reports of lost or stolen medicine

- Inconsistent symptoms

- Physical signs of addiction, such as constricted pupils, itching, dry mouth, difficulty concentrating or withdrawal,

such as dilated pupils, increased heart rate, hypertension, diarrhoea, muscle cramps, frequent yawning, rhinorrhoea,

lacrimation

Prescribing oxycodone

If the clinical decision to use oxycodone is made, the following prescribing points may be helpful.

Opioid-naive patient

The usual oral starting dose in opioid-naive patients for severe pain is:

- 5 mg oxycodone, every four to six hours, increased as necessary according to response (OxyNorm is the current funded

immediate release brand)

- Oxycodone may then be given orally as a modified release preparation (OxyContin is the current funded controlled release

brand), every 12 hours once the 24 hour opioid requirement has been established11

N.B. Modified release preparations of any opioid must not be halved, chewed, crushed or dissolved as this may lead to

a rapid release of the drug and potential overdose. Lower starting and maintenance doses are recommended in people with

poor renal and hepatic function and in elderly people as they may be more sensitive to adverse effects.11,12 eGFR

should also be monitored if oxycodone (or any opioid) is used long-term.1

Changing from morphine

Changing from morphine to another strong opioid such as oxycodone, due to intolerable adverse effects, should be a more

common scenario than beginning with oxycodone as the strong opioid for pain relief.

When changing from morphine to oxycodone, use the equivalent morphine dose. The potency ratio is approximately 1.5:1

to 2:1, i.e. 10 mg oxycodone is equivalent to 15 to 20 mg oral morphine.11

Remember the ABC’s - antiemetic, breakthrough dose, constipation

As with other opioids, oxycodone is associated with adverse effects such as drowsiness, dizziness, hypotension and respiratory

depression. Nausea, vomiting and constipation are common, affecting up to 60% of patients taking opioids. Tolerance to

nausea and vomiting usually occurs within the first week of treatment, but constipation can persist for the entire course.13

Constipation

Prescribe a combination stimulant plus softener laxative, e.g. docusate sodium with sennosides, and advise the patient

to increase fluids and fibre intake.

In cases where constipation is unable to be effectively managed, consider switching to fentanyl patches (if chronic

pain and stable opioid requirements) as fentanyl is associated with less constipation than either oxycodone or morphine.1

Nausea

Prescribe an antiemetic, e.g. metoclopramide or haloperidol, if nausea is intolerable.

Slow dose titration can also help to reduce the incidence of nausea and vomiting.1

Breakthrough pain

Prescribe an extra dose of short-acting oxycodone for breakthrough pain at 1/6th of the 24 hour dose

For example, if the regular dose is OxyContin 30 mg, twice daily (60 mg in 24 hours), then prescribe OxyNorm 10 mg with

instructions to take a maximum of one extra dose, two to four hourly (depending on clinical condition), for pain which

is not controlled by the regular regimen. If three or more extra doses are needed within 24 hours, this would be an indication

that a review of pain control is required.

Stepping down dose

Regularly check pain levels with the patient. When the pain diminishes, step-down the dose of oxycodone, replace with

alternative milder analgesia weaker opioid, such as codeine or paracetamol, if required, and then cease analgesia.

Interactions with other medicines

As with all opioids, when oxycodone is used with other sedating medicines, drugs or alcohol, there is additive depression

of the central nervous system, including respiratory depression. Careful consideration should be given to concurrent prescription

of benzodiazepines with strong opioids such as oxycodone.

Oxycodone is partly metabolised by CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 enzymes. Concomitant use with other medicines and substances which

inhibit these enzymes will theoretically result in an enhanced effect of oxycodone and potentially fatal respiratory depression.

CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 inhibitors, such as fluoxetine, erythromycin, azole antifungals and grapefruit juice, should be used

with caution or avoided in patients taking oxycodone.11,14,15

In contrast, St John’s wort is a CYP3A4 enzyme inducer, especially with prolonged use.16 Concurrent

use of St John’s wort with oxycodone may result in a reduced analgesic effect, therefore this combination should

be avoided.