Published: 20th September 2024

Key practice points:

Understanding and preventing medicine misuse:

- Formulate a practice strategy for prescribing medicines with a high potential for misuse, including opioids, sedatives, hypnotics, quetiapine and gabapentinoids

- Have a clear and open discussion with the patient when first prescribing these medicines and at subsequent reviews. Provide the patient with information about the purpose of treatment, expectations, benefits and risks.

- Limit the initial supply of medicines with the potential for misuse to establish the expectation that treatment is temporary and to reduce the risk of long-term use

- A key strategy to avert misuse in people with risk factors is to prescribe using close dispensing arrangements, e.g. annotating “weekly dispensing” on the prescription

- Set individualised and functional goals for treatment, regularly assess progress, and review continuation of pharmacological treatment when improvements are no longer taking place or treatment is not effective

- Document strategies relating to minimising the risk of medicine misuse in patient notes

- Pharmacists have a role in working with primary care prescribers to help identify and prevent prescription medicine misuse and in guiding patient’s decisions when purchasing over-the-counter medicines with potential for misuse

Detecting and managing medicine misuse:

- Be clear about the difference between misuse of medicines and substance use disorder; there are certain requirements under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 for managing patients who have developed a substance use disorder to a controlled drug

- Medicine misuse may be characterised by escalating doses or frequency of use, or continuation of a medicine when it is no longer clinically required

- Key features of a substance use disorder include loss of control, cravings, compulsive use and continued use despite adverse consequences. It is distinct from physical dependence.

- If there is evidence of medicine misuse, initiate a conversation with the patient, with the aim of supporting them to stop the medicine through gradual dose reduction and reassurance that their condition will be managed; several conversations may be required before the patient is ready to begin the taper

- If a patient has developed a substance use disorder to a controlled drug, they should be referred for treatment to an addiction service

- Discussion with, or referral to, a pain or addiction medicine specialist may be appropriate for some patients, e.g. those with a previously unsuccessful taper attempt, a history of substance misuse or a significant mental health condition, those experiencing significant withdrawal symptoms or if opioid substitution treatment (OST) is required

- Other patients can be managed in primary care, provided they have adequate support at home

- There is little evidence of how frequently doses should be reduced, by how much and over what time frame, and it also depends on the medicine being tapered. This should be individualised depending on the patient’s clinical circumstances; a decrease of 10% per week or month is a reasonable initial step.

- If patients are misusing multiple medicines, reduce one at a time. The optimal order of deprescribing is uncertain in the literature, so this decision can be made pragmatically.

- Recommend non-pharmacological strategies (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy, relaxation and mindfulness techniques, sleep hygiene) throughout the dose tapering process to help with managing the original indication (e.g. pain, insomnia) or symptoms of withdrawal

- Adjunctive pharmacological treatments are not routinely required but may be prescribed in some clinical situations, e.g. antidepressants, antinausea medicines, medicines for gastrointestinal symptoms, paracetamol or NSAIDs for pain. If there is concern about whether a certain medicine should be added, discuss with an addiction or pain medicine specialist.

- Frequent review is required during the dose tapering process (either in person or via phone). Initially, monitoring occurs more often, e.g. daily or weekly, and reduces in frequency over time, e.g. monthly.

- Withdrawing a patient from a misused medicine may take a significant amount of time; prepare to maintain patients on low doses for an extended period of time if they are unable to complete the taper

This is a revision of a previously published article. What’s new for this update:

- A general article revision

- The addition of a national prescribing snapshot for medicines of misuse

- Section added on the legal requirements when prescribing controlled drugs

- Section added on the general principles for deprescribing medicines of misuse

- Section added on approaching the conversation of deprescribing

- Deprescribing summaries included for opioids, benzodiazepines and zopiclone and gabapentinoids

In most cases, people do not set out to misuse medicines that are prescribed to them. It may begin with taking an occasional extra dose, taking two tablets instead of one or taking an “as needed” medicine regularly regardless of symptoms, but over time neurological changes occur, and control is lost over these decisions. The medicine is then perceived as a necessary means to function day to day and the person becomes trapped in a cycle of medicine misuse.

The reasons why people misuse medicines are multi-factorial and complex, including psychological and biological factors, coping mechanisms for pain, emotional distress and other symptoms, lack of family and social support, adverse living circumstances and challenging or traumatic life events.1 However, anyone can misuse medicines, including those with a higher level of social support, education and socioeconomic status (sometimes referred to as the “hidden population” in terms of medicine misuse).1

Prescribers also influence medicine misuse.1 Prescribing inappropriately or continuing to prescribe a medicine without assessing ongoing benefit can contribute to medicine misuse, e.g. prescribing analgesia for pain without review, prescribing a higher potency opioid than is needed, prescribing a benzodiazepine for insomnia without first recommending behavioural techniques for sleep.

When any medicine is prescribed, especially those that have the potential for misuse, the responsibility lies with the prescriber to set the boundaries for use, by ensuring that the patient understands why, how and when to use it and for how long.1 Set an expectation that treatment is temporary until functional goals have been achieved and outline the potential for harm or misuse of a medicine to the patient. The dispensing pharmacist should reiterate this information. Patients have a responsibility to take the medicine as directed for the purpose that it was prescribed.

Medicine misuse is generally described as using a medicine in a manner or dose other than prescribed.2 The most common scenario in a primary care setting is a person who is taking a medicine for the purpose it was prescribed, e.g. an opioid for lower back pain, but at a higher dose, increased frequency or for a longer duration than needed.1 Sometimes, medicines may be misused for a purpose they were not prescribed for, e.g. analgesia taken for emotional pain and distress. When medicine misuse becomes problematic, it may be classified as a substance use disorder, which is measured on a continuum from mild to severe (see: “Substance use disorder”). This encompasses people who obtain medicines for the sole purpose of gaining a “high” (i.e. without a legitimate indication for the medicine) or for diversion (i.e. selling to others).2

Medicines with higher potential for misuse include opioids (e.g. oxycodone, morphine, tramadol, codeine), sedatives and hypnotics (e.g. benzodiazepines, zopiclone), gabapentinoids (i.e. gabapentin and pregabalin), stimulants (e.g. methylphenidate, dexamfetamine), phentermine and quetiapine.2, 3

Substance use disorder

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR) set criteria for the diagnosis of substance use disorder (addiction). Individual substances are defined, e.g. alcohol use disorder, opioid use disorder, but the diagnostic characteristics of most of these disorders are the same.8

Substance use disorder is measured on a continuum from mild (two to three criteria) to severe (six or more criteria), based on the following criteria:8

- Taking the substance in larger amounts and for longer than intended

- Persistent desire to cut down or quit but not being able to

- Spending a lot of time obtaining, using or recovering from use of the substance

- Craving or a strong desire to use the substance

- Unable to carry out major obligations at work, school or home due to substance use

- Continued use despite it causing significant social or interpersonal problems

- Stopping or reducing important social, occupational or recreational activities due to substance use

- Recurrent use of the substance in physically hazardous situations

- Consistent use of the substance despite acknowledgement of persistent or recurrent physical or psychological difficulties from its use

- Reduced effect with continued use or needing to take more of the substance to achieve the desired effect (tolerance)

- Development of withdrawal symptoms, which can be relieved by taking more of the substance

N.B. Tolerance and withdrawal can occur with regular prescribed use, and alone are not sufficient to make a diagnosis of substance use disorder.8

The magnitude of medicine misuse is unknown

There is limited evidence on the magnitude and extent of prescription medicine misuse in New Zealand, and much of it is unlikely to be reported. Issues related to opioid and benzodiazepine misuse are the most well documented. The majority of opioid misuse in New Zealand is from prescription opioids rather than illicit opioids such as heroin (N.B. The most commonly illicitly injected opioid in New Zealand is methadone but the most common injected illicit drug is methamphetamine).4 Concern has also been expressed about pregabalin and gabapentin misuse in New Zealand.5, 6

See: “National prescribing snapshot: medicines of misuse”, for an overview of long-term use of opioids, benzodiazepines/zopiclone and gabapentinoids in New Zealand.

For further information on opioid prescribing in New Zealand, see: bpac.org.nz/2022/opioids.aspx

For further information on benzodiazepine and zopiclone prescribing in New Zealand, see: bpac.org.nz/2021/benzo-zopiclone.aspx and bpac.org.nz/report/snippet/zopiclone.aspx

National prescribing snapshot: medicines of misuse

In New Zealand, one-quarter (24.6%) of patients who were dispensed opioids, benzodiazepines/zopiclone or gabapentinoids in 2023 were taking these medicines long-term*; this figure was highest for gabapentinoids (42.1%) and lowest for opioids (13.6%) (Table 1).7 Medicines with high potential for misuse should generally only be used short-term. However, there will be some clinical scenarios where long-term use is appropriate, e.g. while awaiting surgery, cancer-related pain, neuropathic pain, epilepsy. National dispensing data suggest that there may be a number of patients who have remained on these medicines inappropriately.

*Defined as the number of registered patients dispensed the medicine in at least three out of four quarters in 2023, and they must be prescribed ≥ 15 tablets in each prescription or ≥ 45 tablets in each quarter of any strength. We acknowledge this is an imperfect measure of long-term use, but this approach is intended to account for differences in prescribing periods between medicines, alternate daily or half tablet dosing and eliminates multiple short-term uses.

Table 1. Number of patients dispensed opioids, benzodiazepines/zopiclone and gabapentinoids long-term in 2023.7

|

| All patients

| Long-term patients

|

| Opioids |

704,775 |

95,663 (13.6%) |

| Benzodiazepines + zopiclone |

398,119 |

72,263 (18.2%) |

| Gabapentinoids |

135,640 |

57,140 (42.1 %) |

Dispensing data indicate a high proportion of ongoing use

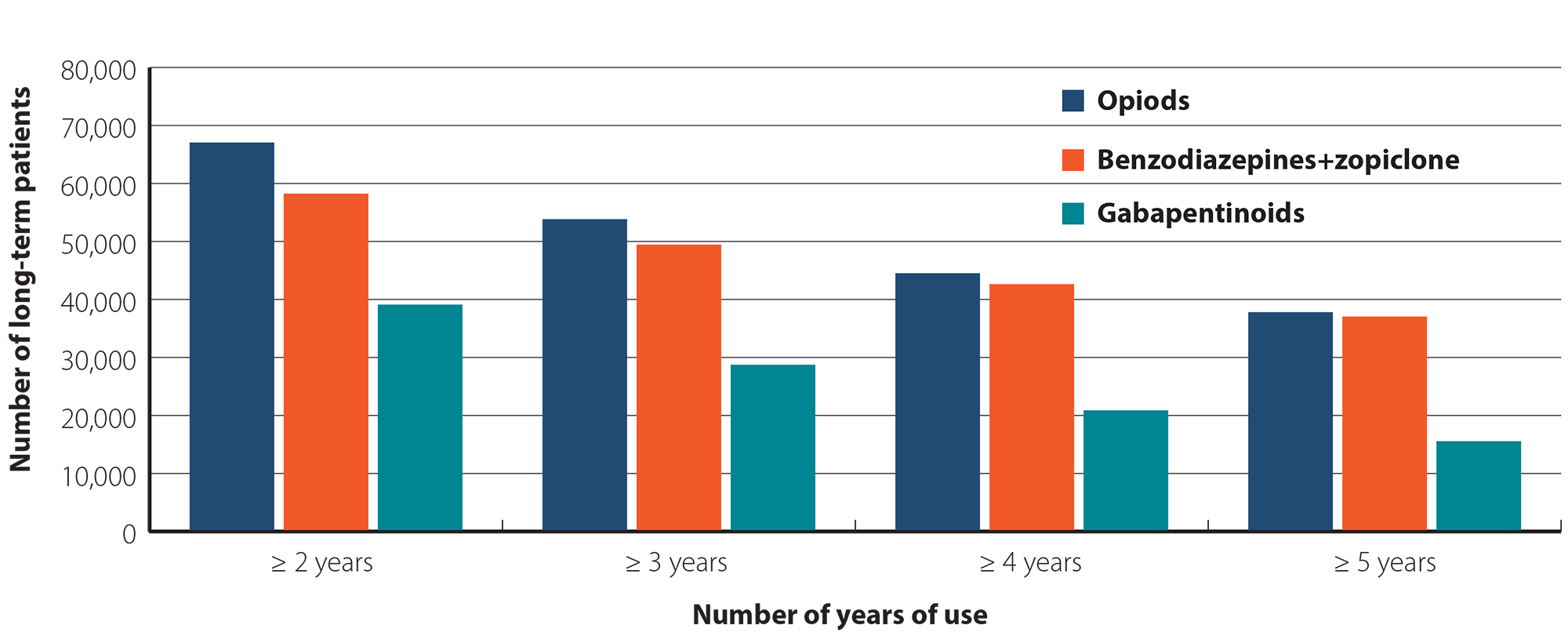

Just over 80% of patients taking benzodiazepines/zopiclone long-term in 2023 had been dispensed prescriptions for two or more years (Figure 1); this number was slightly lower for opioids (70%) and gabapentinoids (68%).7 The duration of use declined with each additional year, but more than half (51%) of long-term users of benzodiazepines/zopiclone, slightly fewer opioid users (40%) and just over one-quarter (27%) of gabapentinoid users had been dispensed the medicine for at least five years. The number of people using opioids may have reduced over time partly due to use in terminal illnesses.

Some people are taking multiple high-risk medicines long-term. In 2023:

- 17,386 people were dispensed opioids + gabapentinoids long-term

- 15,458 people were dispensed opioids + benzodiazepines/zopiclone long-term

- 8,108 people were dispensed benzodiazepines/zopiclone + gabapentinoids long-term

- 3,788 were dispensed opioids + benzodiazepines/zopiclone + gabapentinoids long-term

Figure 1. Number of patients taking opioids, benzodiazepines/zopiclone or gabapentinoids long-term in 2023, who were dispensed the medicine for ≥ 2, 3, 4 or 5 years.

The most common starting point for medicine misuse is when a medicine is prescribed for an acute problem, without a plan in place for what specific symptoms it is being used to treat and likely outcomes or benefit, an agreed upon dosing frequency and duration of treatment and a discussion about the potential risks. It is also acknowledged that some patients will determine their own regimen, despite appropriate and comprehensive advice.

Medicine misuse is also possible when long-term use of a high-risk medicine is indicated and appropriate, e.g. pain related to a terminal illness or cancer, waiting for surgery. For example, when the dose is continually escalated without associated benefit.

Most of the published literature on strategies to minimise medicine misuse relates to opioid prescribing. The general principles of this advice, however, can be applied to most medicines with the potential for misuse.

Prepare a practice strategy in advance

Primary care practices should agree on a policy for prescribing and reviewing patients taking medicines with a high potential for misuse.1 Document treatment plans in the patient’s notes so that other clinicians in the practice can follow the protocol.1 The Medical Council of New Zealand recommends considering the following points when prescribing a high-risk medicine:9

- Do not prescribe more than one to three days’ supply of medicine to a new or unfamiliar patient without having the opportunity to comprehensively assess the rationale for treatment and their current treatment

- Establish contact with the dispensing pharmacist to seek information about any early requests for repeats and to receive feedback about future dispensing (if there is suspicion or high risk of medicine misuse)

- Be aware of pressure to prescribe, prescribing in isolation from practice colleagues, or repeating a prescription from another prescriber without reassessment of need

- Be satisfied that ongoing prescription of a medicine with potential for misuse is clinically indicated and evidence-based

Consider how to manage prescription requests via online patient portals or telephone. Agree on a policy for repeat prescription requests, e.g. no early prescriptions and patients must be reviewed in person regularly, such as three-monthly for those taking opioids that are prescribed monthly.1 Prepare a practice strategy/dialogue for responding to inappropriate requests for medicines with the potential for misuse and familiarise yourself with local referral protocols to specialist alcohol and drug services.1

Examples of practice policies and dialogues are available from: www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/drugs-of-dependence/part-a

New Zealand drug and addiction resources and services:

Principles of safer prescribing of medicines with potential for misuse

Start by considering: “Can I recommend something else?”

If a medicine is being prescribed for symptomatic relief, consider non-pharmacological management strategies that could be trialled first, and continued alongside any pharmacological treatment.1, 3 For example, there are various behavioural techniques and environmental interventions that should be trialled in most people before considering a hypnotic medicine for insomnia; melatonin may also be an option. Also consider the appropriateness of the medicine for the clinical scenario, e.g. paracetamol or a NSAID instead of an opioid for mild to moderate pain.

For further information on managing chronic pain and insomnia, see: bpac.org.nz/2018/opioids-chronic.aspx and bpac.org.nz/2017/insomnia-1.aspx

For further information on prescribing opioids, see: bpac.org.nz/2022/opioids.aspx#recommendations

Free New Zealand-based online CBT courses on topics such as managing insomnia and anxiety are available from Just a Thought: www.justathought.co.nz

Prescribing principles

The following principles can be applied to medicines with potential for misuse:1, 3

- Aim to diagnose and treat the underlying cause of symptoms; if this is unclear, discussion with a pain service may help with determining what type of pain is present, e.g. nociceptive, neuropathic, which can guide treatment choice

- Assess psychological wellbeing and risk of addiction (see below for examples of risk factors). Opioid risk tools are available, e.g. www.mdcalc.com/calc/1757/opioid-risk-tool-ort-narcotic-abuse.

- Discuss all available treatment options, particularly non-pharmacological and coping strategies

- Select medicines based on evidence of effectiveness, and discuss the anticipated benefits and possible risks of treatment with the patient, including tolerance, dependence and addiction

- Establish personalised goals of treatment, e.g. agree on functional achievements identified by the patient, explain that treatment will be tapered and stopped if the intended outcomes of treatment are not met, or adverse effects occur

- Initiate a medicine for a trial period before assessing its effect and deciding whether to continue treatment

- When assessing the overall benefit of treatment after a medicine has been initiated, consider the effect on symptoms, improvements in activity/functional goals, adverse effects, aberrant behaviours (e.g. escalating doses, early requests for repeats) and any change in mood or psychological wellbeing

- Periodically review the underlying diagnosis and influence of the patient’s co-morbidities on treatment success

- Provide a brief written treatment plan to the patient that outlines how the medicine should be taken (dose, frequency, duration), what the goals of treatment are, how often they will be assessed, how and when the medicine will be discontinued and what to do if symptoms are not controlled or goals are not met

- Document the treatment plan in the patient’s notes; also record a measure or description of pre-treatment symptoms and function and reassessment of these measures

- Do not automatically issue repeat prescriptions or increase doses of high-risk medicines prescribed by another healthcare professional without considering the indication and clinical context for the patient yourself. If you feel uncomfortable to prescribe but the patient’s supply is due to run out, it is reasonable to prescribe enough medicine at the usual dose until they are able to be reviewed by their regular prescriber.

- Use electronic prescribing direct to a nominated pharmacy to eliminate the possibility of lost prescriptions

Information on good prescribing practice is available from the Medical Council of New Zealand: www.mcnz.org.nz/our-standards/current-standards/prescribing/

- Factors that increase the risk of medicine misuse include a personal or family history of substance use disorder or misuse (including intravenous drug use [hepatitis C status may be an indicator of this], alcohol and nicotine) and a current or past history of a serious mental health condition, e.g. bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, personality disorder.3, 6, 10 Psychosocial factors can also increase the likelihood of medicine misuse, such as a personal or family history of addictive behaviours or legal issues related to alcohol or illicit drugs and recent life changes, e.g. bereavement, social isolation, stress, financial pressures. A systematic review found inconsistent evidence of any correlation between opioid misuse and demographic factors such as sex, employment status, ethnicity, marital status or level of education.11

- The dose prescribed, and the number of days’ supply of a first prescription influences the likelihood of ongoing use and therefore medicine misuse.12, 13 For example, an analysis of almost 1.3 million patient records in the United States found that among patients with non-malignant pain prescribed an opioid for the first time,* the key factors that increased the probability of long-term use were when a first prescription supply exceeded 5, 10 or 30 days, after a second or third prescription and when the total cumulative dose reached ≥ 700 mg morphine equivalent.13 There is a risk of long-term use for patients prescribed opioids for any length of time (6% of all patients prescribed opioids were still taking them one year later), but this risk increases with the number of days supplied; 14% of patients whose first prescription was for ≥ 8 days and 30% of those whose first prescription was ≥ 31 days were taking opioids one year later. Approximately 14% of patients who received a repeat or second prescription for an opioid were still taking opioids after one year. Patients who were initiated on a long-acting opioid had the highest probability of long-term opioid use (see below). Patients taking tramadol had the second highest probability of long-term opioid use, however, this may reflect choice of medicine for long-term pain.13

- * Patients were included if they had more than six months without an opioid prescription prior to this prescription

- Immediate- versus modified-release opioids. Most patients who require an opioid short-term for non-malignant pain should be initiated on an immediate-release formulation as they can be dose-adjusted or stopped quickly if not tolerated.12, 14 Modified-release opioids are likely to cause more sedation and respiratory depression, can be more easily overdosed and are associated with a higher risk of long-term use.3, 12, 14 There are some scenarios where a modified-release opioid may be considered, such as if tolerance or withdrawal issues occur in a patient taking an immediate-release formulation.

Prescribing to patients with risk factors

Depending on the individual scenario, a patient’s risk factors may mean that a certain medicine is not appropriate, or that a medicine can be used but with additional precautions and monitoring put in place, e.g. restricting initial supply to a few days only before review. N.B. We acknowledge this might not be possible with resource and time constraints for primary care and cost barriers for the patient for additional appointments and prescription fees.

A key strategy to avert misuse in people with risk factors is to prescribe using close dispensing arrangements. Regulations state that Class B opioids (e.g. morphine) are dispensed every ten days and Class C controlled drugs (e.g. codeine, benzodiazepines) monthly, unless specified otherwise. Dispensing a shorter days’ supply of medicines can help to avoid misuse. Consider implementing a practice policy that these medicines are annotated with “weekly dispensing” or similar, which ensures that patients are always due to collect their medicines on the same day each week.* This allows for easier identification of patients who regularly request earlier collection of their repeats or new prescriptions before they are due.

* If possible, avoid Mondays and Fridays for medicine collection as public holidays generally fall on these days

Medicines with a high potential for misuse (e.g. opioids and hypnotics) are usually contraindicated if a patient has a known substance use disorder, e.g. alcohol, prescription medicines, illicit drugs (see: “What are the legal requirements when prescribing controlled drugs?”); discuss treatment options with a pain or addiction medicine specialist.1 If opioids are required for acute pain, the patient should not be denied them, however, measures need to be put in place to safeguard their use.

A Restriction Notice can be applied for if a patient has been obtaining a prescription medicine over a prolonged period and there is concern that they are likely to seek further supplies from other sources (i.e. “doctor shopping”), although this does not always guarantee that alternative supply will not occur. For further information, see: www.health.govt.nz/regulation-legislation/medicines-control/drug-abuse-containment

Opioid risk tools are available: www.mdcalc.com/calc/1757/opioid-risk-tool-ort-narcotic-abuse – used to assess risk prior to prescribing and acfp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Prescription_Opioid_Misuse_Index.pdf – may assist in detecting problems in patients already taking opioids (a score of two or more indicates that a problem is likely)

Review the rationale for continued prescribing

Review medicines that may no longer be beneficial or appropriate. For example, patients discharged from hospital with multiple pain medicines can have a tapering protocol put in place and strong opioids stepped down to weaker analgesic options as their pain resolves.

A more complex scenario is taking over the care of a patient who is already established on long-term treatment and may have been for many years. It is never too late to apply the principles of safer prescribing and establish goals for treatment and a strategy to cautiously reduce and discontinue medicines if use is not beneficial (see: “General principles for deprescribing medicines of misuse”). Contact the local pain team or addiction services for advice as needed.

What are the legal requirements when prescribing controlled drugs?

In New Zealand, the prescribing of controlled drugs is tightly regulated to ensure safety and minimise misuse. The key legal requirements for prescribers include:

Classes of controlled drugs

Controlled drugs are classified into three classes under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975:

- Class A: Very high risk of harm (e.g. heroin, LSD)

- Class B: High risk of harm (e.g. morphine, oxycodone, fentanyl)

- Class C: Moderate risk of harm (e.g. codeine, tramadol, benzodiazepines)

N.B. Gabapentin and pregabalin are not controlled drugs.

Prescribing limits

Amendments to the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 1977 in October, 2023 (Misuse of Drugs Amendment Regulations [No 2] 2023) set new specific limits on the maximum period of supply of controlled drugs, i.e. 30 days for Class B opioids (dispensed in 10 day lots); N.B. Opioid substitution treatment is excluded from this rule, 30 days for Class C opioids (dispensed in a single lot) and 90 days for non-opioid Class B and C controlled drugs (dispensed in monthly lots). The Ministry of Health, Manatū Hauora, states that these are maximums allowed under the law, but they are not necessarily indicative of appropriate practice. Prescribers are recommended to follow current best practice guidance and work within their scope of practice.

Prescribing to people dependent on controlled drugs

Under Section 24 of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975, it states that:

A health practitioner commits an offence if, in the course of, or for the purpose of, treating a person for drug dependency, the health practitioner —

(a) prescribes, administers, or supplies a controlled drug for or to the person; and

(b) does so although having reason to believe that the person is dependent on that or any other controlled drug

These restrictions under this subsection of the Act do not apply to prescribers who are working in a specified place (e.g. a specialist drug addiction service) or who have been authorised to prescribe controlled drugs by a prescriber working in such a place. Section 24 of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 allows the Ministry of Health, Manatū Hauora, to issue a New Zealand Gazette notice for both prescribers and the specialist service. The gazetted practitioner can authorise other prescribers to also prescribe for the purposes of treating addiction, e.g. a primary care prescriber authorised to provide prescriptions for methadone as part of an OST programme.

Despite following principles for prescribing to avoid medicine misuse, some patients will inevitably still misuse their medicine. Behaviours or clinical features that may indicate medicine misuse by patients include:1

- Requesting a specific medicine and being unwilling to accept an alternative

- Being more concerned about the medicine rather than the condition that it is being used to manage

- Self-directed dose escalations*

- Requesting repeats or new prescriptions earlier than expected

- Claims of lost prescriptions (can be mitigated by using electronic prescriptions direct to the pharmacy) or medicine supply

* Escalating dose requirements are a normal physiological response to some medicines, e.g. opioids and benzodiazepines, however, patients should be advised against initiating dose increases themselves. Clinicians should also avoid dose increases without assessing the patient.

Strategies for confirming medicine misuse

There are several strategies that can be implemented to help detect medicine misuse. The challenge with this, however, is that although it promotes transparent communication between the clinician and the patient, it can imply a lack of trust. In addition, there is limited evidence about how effective these strategies are in reducing medicine misuse.11 Therefore the following strategies should be undertaken with caution and judgement of the individual clinical scenario:1, 11

- Medicine counts – ask the patient to bring in their supply of medicine and check this against the expected number of tablets remaining

- Utilise electronic databases such as Testsafe or HealthOne – to track the prescription and dispensing history of the patient

- Formal treatment contract (as opposed to a general treatment plan) – specifying that the patient agrees to receive prescriptions from only one prescriber and one pharmacy (necessary if prescribing a restricted medicine), not to divert the medicine and not to request early repeats

- Direct communication with the dispensing pharmacist, e.g. sharing information about potential medicine misuse, communicating if there is a reason for a repeat prescription to be released early

- Increasing the dispensing frequency to weekly (or even more frequently) may assist pharmacists in detecting misuse if patients request earlier repeats because their medicine supply is not lasting as long as expected

- For fentanyl patches, an option for pharmacists to deter or identify potential misuse is to date the patches and request that the patient return used patches to exchange for new ones

- Urinary drug testing – this is generally not useful, or practical, to detect prescription medicine misuse as it will simply demonstrate if a patient has taken that medicine (if included in the assay). However, it could be considered if there is a need to detect use of other medicines or illicit substances or to confirm that the medicine is being taken (and not diverted).

Misuse of over-the-counter medicines: role of community pharmacists

Many medicines are available for purchase in pharmacies that have a similar potential for misuse as prescription medicines, e.g. sedating antihistamines, laxatives, loperamide, cough and cold preparations (e.g. pseudoephedrine), analgesics.10, 15 Pharmacists have an opportunity to educate patients about appropriate over-the-counter (OTC) medicine use, including strategies to avoid them losing control of their use of a medicine.15 The patient-pharmacist interaction can strongly influence decision making in terms of which medicines are purchased and how they are used.15

In a patient encounter involving the purchase of an OTC medicine with potential for misuse, the pharmacist should consider factors such as:15

- Inaccurate self-diagnosis

- Inappropriate dose

- Prolonged use

- Adverse effects and interactions with other medicines (especially in older people due to polypharmacy)

- Misconceptions or lack of information about risk

- Direct to consumer advertising of products, resulting in inappropriate product selection

Relying solely on the appearance of a person to “screen” for misuse is not useful as there is no particular profile of a person who is likely to misuse medicines.

Strategies to reduce misuse of OTC medicines include:15

- Train staff to recognise possible OTC medicine misuse and follow set procedures; include locum pharmacists, weekend/casual staff and staff not usually involved in the sale of medicines

- Access information on local drug misuse; liaise with other pharmacies and general practices in the area

- Refer all requests for certain medicines to the supervising/senior pharmacist

- Restrict the maximum quantity of medicine sold to an individual patient

- Do not display certain medicines openly

- Decline repeated sales of a certain medicine to an individual patient, e.g. restricted medicine sales that are noted, or known patients with substance misuse. Also be aware of and use the Restricted persons list.

- Educate patients about the misuse potential of certain medicines

- Provide oral or written medicine information

- Refer the patient to their primary care clinician if there are any concerns

- Become familiar with local alcohol and drug services that patients can be referred to

- Utilise electronic databases that allow access to prescribing and dispensing records such as Testsafe and HealthOne; this can provide essential information before dispensing a prescription or recommending a ‘pharmacy-only’ medicine

Some pharmacy groups have resources and guidance on substance misuse for members, e.g. Pharmacy Practice Guidelines available from The Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand.

When medicine misuse has been identified in a patient, the medicine should ideally be withdrawn gradually over time.3 Avoid abrupt discontinuation due to the risk of severe withdrawal symptoms (e.g. seizures with benzodiazepines)16, unless patient safety is at risk (e.g. high risk of overdose).3 Aim for full cessation, but any reduction in dose is still beneficial.

One of the more challenging aspects of withdrawing medicines of misuse is deciding whether the patient can be successfully managed in primary care or whether they require more specialised support. This decision will often also depend on clinician experience.

- Patients with a substance use disorder to a controlled drug should be referred for treatment to a gazetted addiction service under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 (see: “What are the legal requirements when prescribing controlled drugs?”). Opioid substitution treatment (OST) is usually initiated for patients with an opioid use disorder.

- Consider referral to a specialist service for patients who have had a previously unsuccessful taper attempt in primary care or have a significant or untreated psychiatric co-morbidity1, 17, 18

- Referral to addiction services for OST may be needed for some patients taking opioids who do not meet criteria for an opioid use disorder, e.g. those taking high doses, signs of aberrant behaviour

- Other patients can be encouraged to engage with a plan to slowly decrease their dose within a primary care setting, provided they have adequate support at home

Undertaking a medicine withdrawal in general practice

Provide the patient with information about the dose tapering process, including potential withdrawal symptoms and discuss and document a tapering plan.3

The tapering protocol depends on a range of factors, including:3, 12, 18, 19

- Duration of medicine use

- Total daily dose

- Pharmacokinetic profile of the medicine (e.g. short- versus long-acting)

- Underlying condition being treated

- Co-morbidities (e.g. depression)

To support patients to succeed during withdrawal there needs to be a good understanding between the patient and prescriber about what dose and frequency of medicines they have been taking. If a tapering schedule is determined based on the original prescribed dose, and access is restricted to one prescriber and a smaller quantity of medicine dispensed at one time, it may not be adequate to prevent significant withdrawal symptoms if the patient has actually been taking more than this. Therefore, the starting point needs to be based on an accurate measure of the amount and frequency of medicine misuse. Initiate a gradual taper once the patient has adjusted to, and is tolerating, the new prescribing and dispensing regimen.

There is little evidence of how frequently doses should be reduced, by how much, or over what time frame; this should be individualised to each patient and the medicine being misused, but withdrawal should generally be slow, e.g. starting with a 10% reduction in dose per week. Actively involving the patient in decision-making about the withdrawal regimen is essential. Contact the local pain or addiction medicine service for advice and support as needed during the dose tapering process.20

Increase dispensing frequency

One strategy to support deprescribing is to increase the dispensing frequency of the medicine, e.g. to weekly, set days of the week or daily (however, this approach will not be appropriate for all patients, e.g. if a pharmacy is not easily accessible).1 If possible, avoid Mondays and Fridays for medicine collection as public holidays generally fall on these days. More frequent dispensing can help patients adhere to the withdrawal plan and reduces the risk of taking doses early and running out, which in turn can lead to withdrawal symptoms or pressure for another prescription or picking up repeat prescriptions early. More frequent contact with the pharmacist can also increase the amount of support the patient is receiving and helps to reduce anxiety about the withdrawal plan.

Withdrawing more than one medicine

For patients who are misusing multiple medicines concurrently, e.g. opioids and benzodiazepines, the optimal order of deprescribing is uncertain in the literature (e.g. some guidelines recommend deprescribing opioids first, while others advise the opposite).21 Only one medicine should be reduced at one time. The decision of which medicine to taper first should be individualised to each patient, considering factors such as dose, original indications for prescribing, co-morbidities or other relevant clinical characteristics, patient preferences and concerns.14, 21 Consult with, or refer the patient to, an addiction medicine specialist (or other appropriate specialist) for guidance on the optimal order of deprescribing, as appropriate.1, 14

Supporting the patient through the process

Frequent review will be required throughout the dose tapering process either in person or via phone, text/email or patient portal. At each review, assess symptoms and signs of withdrawal and make adjustments to the tapering schedule as needed, and assess the patient’s mental health and wellbeing.12, 22

Consider other interventions to support the process of deprescribing and for continued management of the underlying condition or withdrawal symptoms (as needed), e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy, sleep hygiene techniques, implementing advice from a multidisciplinary pain team. Adjunctive pharmacological treatments are not routinely required and introducing more medicines to a person during withdrawal is generally not encouraged. However, adding medicines may be necessary in some cases, e.g. NSAIDs for pain or antidepressants for patients experiencing anxiety or depression.12, 22 Benzodiazepines, clonidine and some opioids (e.g. buprenorphine) may have a role in opioid withdrawal but should not be prescribed to manage withdrawal symptoms without specialist advice.12, 23

Specific tapering guidance summaries are available for:

Approaching the conversation of deprescribing

It can be difficult for patients who have been taking medicines long term to accept the need for deprescribing if they are no longer of benefit or causing harm. Some patients may be distressed, or even become aggressive, when the discussion around deprescribing is raised, which can be challenging to manage.

Consider the following points when approaching the conversation of deprescribing for a patient in whom medicine misuse has been identified. The conversation may need to be repeated several times before the patient reaches a point where they are willing and ready to start the taper. Most of the following relate to deprescribing opioids, but will often also apply to other medicines of misuse:

- Establish a supportive and friendly environment to enable open communication24

- Show empathy and focus discussion on the medicine and outcomes that are important to the patient e.g. their quality of life, harms; express concern about the wellbeing of the patient20, 25

- Use clinical terms and non-emotive language when discussing deprescribing and avoid defining the patient by the misuse, e.g. use the term “pain medicines” rather than “pain killer” and refer to pain as “the pain” rather than “your pain”26

- Discuss that information on the benefits and risks of medicines is constantly evolving, and that this can sometimes lead to changes in prescribing recommendations over time20, 25

- It may be that medicines that were previously thought to be helpful are now proven ineffective or more evidence on their harms has emerged.20 There may be new evidence that other treatments are now more effective than the medicine the patient is currently taking, or the approach to management may have changed, e.g. focus on function rather than pain, non-pharmacological strategies prioritised.

- As the patient’s condition changes, they get older and co-morbidities emerge, a different management approach may be more appropriate

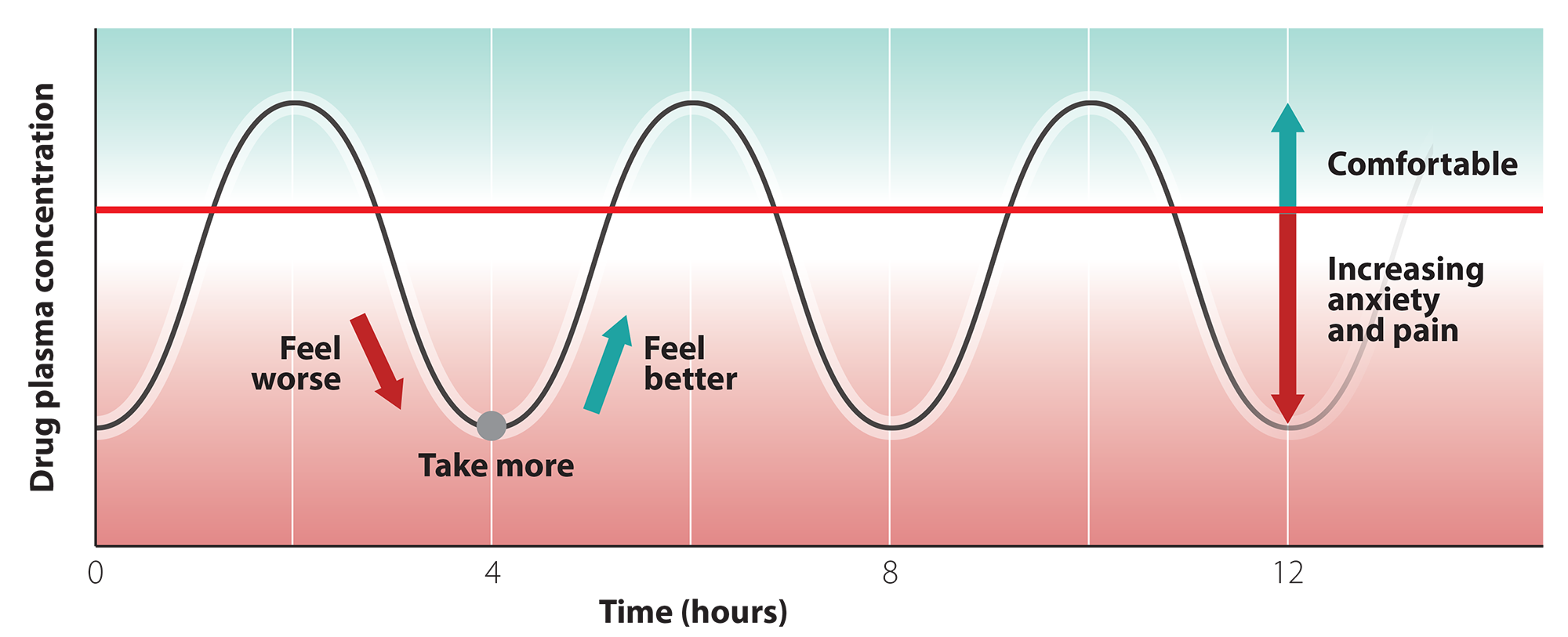

- Explain to patients misusing opioids about the “vicious cycle” of withdrawal, tolerance and hyperalgesia which is preventing them from gaining satisfactory pain relief. The patient may think that an opioid is required to prevent pain from worsening, but it can be difficult for them to understand that the opioid caused this problem in the first place. Doses are typically escalated to meet analgesic requirements, but over time the patient also becomes tolerant to this dose and the cycle repeats until the patient is taking the maximum dose, and this still does not provide adequate analgesia. Figure 2 may be a useful graphic to help explain this concept to patients.

- Explain the limited role of the medicine in long-term symptom management and the associated risks.20, 27 Also discuss the benefits of a taper and that any reduction in dose is beneficial.

- Discuss, validate and address patient concerns and worries about tapering. Ask “how” and “what” questions rather than “why”, e.g. instead of “why do you take the medicine?” ask the patient “what do you find helpful about the medicine?”, “what concerns do you have about reducing the dose or stopping the medicine?”24, 28

- Reassure the patient that there are other management options available to support them throughout the taper and after the medicine is stopped, e.g. non-pharmacological strategies26–28

- The Prescribed Opioids Difficulties Scale may be used to show the patient the extent of the problems that opioids are causing 20

Figure 2. Graphic showing peak/trough of short-acting medicines demonstrating how the trough is associated with mild withdrawal and so taking the next dose makes the patient feel better but only because weaning off made them feel bad initially.

Dealing with aggressive patients

If patients become aggressive, argumentative or hostile after discussing the topic of deprescribing, try to de-escalate the situation by:29

- Communicating in a calm, controlled, confident and respectful manner, e.g. I understand that this is making you feel upset, but I need to discuss this to help you

- Using reflective questioning - repeat back what the patient has told you and frame it as a question, e.g. you are worried that your pain will not be controlled after tapering, is that correct?

- Using clear, direct language and simple explanations

- Being aware of your body language, e.g. turn towards the patient when speaking to them, keep your arms at your sides or in a neutral position, maintain regular eye contact without staring

- Explaining that your actions are focused on providing the best care for them, e.g. I would like to discuss other options that can be used to make the pain or sleep better

- Asking questions that are likely to be answered affirmatively. Answering a series of questions with “yes” can help a patient to perceive the clinician as being sympathetic to their problem or “on their side”.

- Engaging the patient in finding solutions to their problem, e.g. you say you must take the medicine to be able to function or to sleep, is that right? Can you think of some other ways to reduce the pain or techniques or behaviours to help you get to sleep?

- Reassuring the patient that this is a discussion about a plan for slow gradual changes, i.e. that nothing will happen abruptly today

- Involving a colleague who supports your view (although this could be counterproductive and will not be appropriate in every scenario)

For further information on preventing and managing patient aggression and violence, see: www.racgp.org.au/patientaggression