Part 1: Diagnosis and non-pharmacological treatment

Adults with insomnia have difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep with adverse effects on their daytime functioning.

A sleep diary can help with diagnosis and tracking improvements. Non-pharmacological approaches, such as sleep hygiene

and bedtime restriction, are preferred first-line treatments; these are effective and provide greater long-term benefits

than pharmacological measures.

Also see "Part 2: The ideal pharmacological approach for improving sleep"

Key practice points:

- A diagnosis of chronic insomnia can be made based on the patient’s sleep symptoms and daytime fatigue after ruling

out other conditions such as sleep apnoea, dyspepsia, dyspnoea, restless leg syndrome and parasomnias.

- Non-pharmacological treatment is first-line for all patients: in general, most people who have problems sleeping

can benefit from this intervention even if other conditions, such as depression, anxiety or pain, are contributing

to their insomnia.

- Non-pharmacological treatment should aim to address lifestyle factors causing sleep disruption, improve the sleeping

environment and sleeping routine, and strengthen the link between bed and sleeping (sleep hygiene). It can also include

bedtime restriction to maximise sleep efficiency. These behavioural changes form part of cognitive behavioural therapy

for insomnia (CBTi).

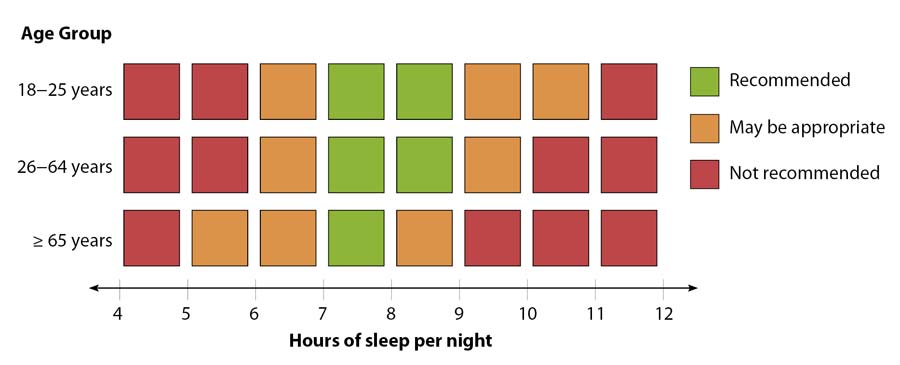

There is a large amount of individual variation in sleep duration and requirement. The optimal recommended sleep

duration for adults ranges from seven to nine hours per night, although some people will require more than this, and

some will function well with less (Figure 1). Daytime fatigue is a key feature of the diagnosis

of insomnia, and is usually regarded as the most important feature, rather than the amount of sleep a person is getting1

Almost everyone will have short-term insomnia at some point in their life, for example due to bereavement, stress

or worry about family, relationships, work or finances. Sleep problems which have lasted for one to three months are

considered chronic insomnia.2–4 Traditionally, a distinction has been made between secondary insomnia, which

arises due to another condition, and primary insomnia where a patient has problems sleeping but where there is no underlying

medical cause.4 However, this distinction is now considered less important because:4, 5

- Primary and secondary insomnia may co-exist

- Insomnia does not always resolve when the secondary cause is treated, e.g. if the patient also has poor sleeping

habits

- Management principles are the same regardless of diagnosis; research increasingly shows that non-pharmacological

approaches can improve sleep in patients who have co-morbid conditions, such as chronic pain, depression or anxiety.

Figure 1: Recommended sleep durations across age groups6

A number of conditions can be associated with disrupted sleep and difficulty staying awake during the day (Table

1).

Chronic insomnia is a diagnosis of exclusion. It is important that treatable conditions which cause sleep disturbances,

such as sleep apnoea, restless leg syndrome or parasomnias, are identified and managed accordingly, which may alleviate

the patient’s insomnia symptoms. However, most people who have problems sleeping can benefit from non-pharmacological

approaches even if other conditions are contributing to their insomnia.

Ask patients about their specific sleep symptoms

Attention to a patient’s specific problems with sleep or waking can help guide diagnosis (Table 2).

Accounts from partners or room-mates may provide useful information such as witnessed apnoeas, kicking or other movements

during sleep.

Ask about daytime symptoms

In patients with chronic insomnia, physical and mental fatigue are more common than a tendency to fall asleep during

the day, which may suggest an alternative diagnosis such as narcolepsy or sleep apnoea.7 If patients have

problems staying awake or have significant fatigue, assess factors such as safety while driving or using machinery,

or while caring for children or others, as reaction times, concentration and judgement may be affected.

Assess medicine or substance use, lifestyle and home factors which could contribute to poor sleep

Factors related to a patient’s lifestyle, prescribed medicines, caffeine intake or sleeping environment could cause

or further exacerbate problems with sleep or fatigue.

Smoking increases sleep latency and causes disturbed sleep later in the night.10 Alcohol may cause initial

sleepiness but can disrupt sleep in the later part of the night.11

Consider use of medicines that are associated with sleep disruption and whether it is possible to discontinue, change

or alter the timing of the medicine, e.g. SSRIs, opioids, beta-blockers (particularly lipid soluble formulations such

as bisoprolol, metoprolol or carvedilol), statins and diuretics.7

Ask about mental health issues and psychological stress

Insomnia is associated with an increased risk of mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety. Conversely,

underlying depression or anxiety can contribute to problems sleeping and can often be the first presenting symptom

of the mental illness. Research shows that improving sleep in these patients benefits their co-morbid depression or

anxiety.13,14

Questionnaires may assist diagnosis

The Auckland Sleep Questionnaire can be used to identify patients who would like help with problems with sleep or

depressive symptoms. The Epworth Sleepiness Score can assist in the diagnosis of sleep apnoea.15

The Auckland Sleep Questionnaire (short version) is available at:

www.goodfellowunit.org/sites/default/files/insomnia/ASQshort_tool.pdf

The Epworth Sleepiness Score is available at:

https://qxmd.com/calculate/calculator_85/epworth-sleepiness-scale

Investigations or referral may be useful for alternative diagnoses

Most patients with insomnia do not require investigations or referral as the history is usually sufficient to provide

a diagnosis. Referral for additional investigations, such as overnight sleep studies, are only likely to be necessary

for patients where there is a suspicion of another diagnosis, such as sleep apnoea, limb movement disorders or suspected

narcolepsy (see: “Types of sleep study”).8, 16

Types of sleep study

Polysomnography, also referred to as a level one test, is an overnight sleep study used in the

diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnoea and sleep movement disorders. It includes an electroencephalogram, electro-oculogram

for tracking eye movements, electromyogram for measuring muscle activation, electrocardiogram, oxygen saturation,

measurement of respiratory parameters and is monitored by a technician.17, 18 A level two test includes

the same measures without an attending technician.18

Level three and four tests use portable equipment which measure oximetry, airflow or respiratory

effort, and unlike level one or two tests can be done at home.18 These have good sensitivity and specificity

for detecting sleep apnoea in patients where there is a high suspicion of having the condition.18 However,

level three and four tests are not useful for diagnosing non-respiratory sleep disorders such as restless leg syndrome;

patients with these conditions may need to pay for polysomnography through a private provider.

A multiple sleep latency test assesses how easily a patient falls asleep and is used in the diagnosis

of narcolepsy.17 It is conducted during the day, typically following an overnight polysomnography assessment.

Table 1: Differential diagnoses which can cause or further exacerbate disrupted sleep, tiredness or non-refreshing sleep.3, 7 ,8

Sleep disorders |

Restless legs syndrome |

For further information, see: www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2012/december/restlesslegs.aspx |

|

Delayed sleep phase disorder |

People with this condition have a circadian rhythm where they tend to go to sleep late, e.g. after midnight,

and wake late in the morning, which impacts on their social, educational or occupational

demands. 9 For further information, see: www.sleep.org.au/documents/item/2683 |

|

Advanced sleep phase disorder |

People with this condition have a circadian rhythm where they feel excessively tired in the evening, go to

bed early, e.g. 8-9 pm, and wake early in the morning.9 For further information, see:

www.sleep.org.au/documents/item/2683 |

|

Narcolepsy |

For further information, see sidebar in: www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2012/november/parasomnias.aspx |

|

Parasomnias |

For further information, see: www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2012/November/parasomnias.aspx |

| Respiratory problems |

Sleep apnoea |

See: “Risk factors and signs and symptoms associated with obstructive sleep apnoea”.

For further information on sleep apnoea, see: www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2012/november/apnoea.aspx |

| Other conditions |

- Depression or anxiety

- Chronic pain

- Chronic fatigue syndrome

- Itch (e.g. atopic eczema, chronic urticaria)

- Menopause

|

Risk factors and signs and symptoms associated with obstructive sleep apnoea12

| Risk factors |

Signs and symptoms |

- Obesity

- Type 2 diabetes

- Congestive heart failure

- Atrial fibrillation

- Treatment refractory hypertension

- Nocturnal dysrhythmias

- Stroke

- Pulmonary hypertension

|

- Witnessed apnoea

- Snoring

- Gasping/choking at night

- Non-refreshing sleep

- Frequent waking

- Nocturia

- Morning headaches

- Decreased concentration

- Memory loss

- Decreased libido

- Irritability

- Excessive sleepiness not explained by other factors

|

For further information on diagnosing and managing patients with sleep apnoea, see:

www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2012/november/apnoea.aspx

Table 2: Features of disrupted sleep and some associated causes3, 7, 8

| In patients with: |

Consider: |

Difficulty falling asleep when they first go to bed |

- The use of stimulants such as caffeine, and medicines with stimulant properties, e.g. pseudoephedrine, methylphenidate

- Restless legs syndrome

- Delayed sleep phase disorder

- Lack of time to unwind, e.g. watching an exciting programme before bedtime

- Anxiety, distress, worry about not getting enough sleep

- Using computers, tablets, phones or reading e-books or books in bed

- Smoking (increases sleep latency and causes disturbed sleep later in the night10)

- Working night shifts or alternating shifts

|

Frequent arousals during the night (or typical sleeping time), also known as “sleep maintenance insomnia” (see:

“Sleep vocabulary”) |

- Sleep apnoea

- The need for frequent urination, e.g. due to use of diuretics or prostatism

- Alcohol use (can disrupt sleep in the later part of the night11)

|

Difficulty getting back to sleep once awake |

- Stress, worry and anxiety

- Other health issues: chronic pain, dyspnoea, itch

- Activities such as using a mobile phone or electronic device after waking

|

Waking up too early |

- Advanced sleep phase disorder

- Too much light or noise

- Stress, worry and anxiety

|

Sleeping, but not feeling refreshed or rested when they wake |

|

Initial management of insomnia is to address any lifestyle factors influencing sleep and to create healthy sleep

habits by encouraging patients to follow sleep hygiene advice (Table 3). This forms part of cognitive

behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi), which is the recommended first-line treatment.7, 19 Subsequent

consultations can be used to intensify treatment if patients have ongoing problems, such as adding bedtime restriction

or additional lifestyle changes.

CBTi is more effective than medicines in the long term

CBTi consists of behavioural changes to improve sleeping patterns and addressing any unhelpful thoughts or beliefs

a patient may have about sleeping. The effects of CBTi will vary, but on average it results in patients getting to

sleep approximately 20 minutes earlier, with 20–25 minutes less time awake at night and an improvement in their subjective

experience of sleep.21 These benefits are similar or better than those obtained with pharmacological approaches.19 A

2012 systematic review concluded that CBTi was at least as effective as medicines in the short-term, and produced more

durable results in the long-term.22 In addition, CBTi is not known to have serious adverse effects.19

Delivering CBTi for insomnia in primary care

CBTi is most successful when delivered over multiple sessions, however, the cost and inconvenience of this may make

more in-depth CBTi difficult for many patients. A useful strategy for clinicians in primary care is to focus on behavioural

changes such as sleep hygiene and modifications to a patient’s sleeping environment (Table 3);

approximately 30% of patients will improve their sleep with sleep hygiene alone.16 Clinicians can also offer

to oversee bedtime restriction (Table 4), which could be done via telephone support, and attempt to identify other

cognitive barriers to good sleep.

Patients can be provided with handouts and encouraged to use books, online resources or apps to assist with behavioural

and cognitive changes to improve sleep.

For example, patient information and printouts are available from:

www.healthnavigator.org.nz/healthy-living/sleep/

Table 3: Sleep hygiene and lifestyle steps patients can take to improve sleep.3

| Treatment or technique |

Advise patients to: |

Keep a routine |

- Go to bed and get up at the same time every day, including weekends or non-work days. Make sure their chosen bedtime

is when they feel sleepy.

- Ideally, avoid napping during the day. If naps are taken, limit them to 20–30 minutes and avoid napping in the

late afternoon or evening.

|

Avoid substances which could interfere with sleep before bedtime |

- Avoid caffeine and energy drinks for several hours or more before bed (or altogether). Caffeine is found in coffee,

black or green tea, energy drinks and some soft drinks, as well as chocolate and guarana.

- Avoid alcohol near bedtime; alcohol can cause initial drowsiness and reduces sleep latency but disrupts sleep later

in the night11

- Cut down on smoking as people who smoke have greater sleep disruption.10 Smoking cessation may be associated

with poor sleep during the withdrawal phase.

|

Keep the bedroom for sleeping and sex |

- Do not watch TV, use electronic devices or read in bed; the light from screens (including e-readers) may affect

sleep by interfering with melatonin production.16

- Get out of bed if unable to sleep during the night, and return only when drowsy enough to sleep

|

Bedroom environment |

- Keep the bedroom a comfortable temperature and dark. Remove any sources of light such as bright clocks or modems.

- Restrict bedroom noise or use earplugs

- Avoid watching the clock if awake at night

- Consider a separate sleeping environment if partner disturbance causes significant difficulty sleeping

- Take steps to prevent mosquitoes and other bugs entering the room or clearing them before bed

|

Prepare for sleep |

- Avoid exposure to bright light in the later evening and during the night (e.g. keep the lights low before going

to bed and do not turn on a bright light to go to the bathroom if you wake in the night), as it may adversely affect

sleep20

- Engage in relaxing activities, such as listening to music, having a bath or more structured relaxation techniques

such as meditation or progressive muscle relaxation20

- Write things down to allow the mind to relax, e.g. in the evening create a list of tasks to remember for the next

day

|

Change daily activities |

- Engage in regular daytime exercise7

- Consider mindfulness exercises or meditation. For further information, see: www.calm.auckland.ac.nz;

a resource for managing stress and improving mindfulness.5

|

For a handout version of this table for patients, see: www.bpac.org.nz/2017/docs/insomnia-patient.pdf

If patients wish to keep track of their sleep, advise them to use a sleep diary. It is not essential

to keep a sleep diary, but some patients find it helpful to record when they go to bed, how many times they wake during

the night and their total sleep time. Completing a sleep diary for two weeks can also confirm that the patient has

an ongoing problem rather than a short-term period of poor sleep, prior to undergoing more intensive management approaches.

Be aware that for some patients recording their sleep may lead to an obsessive focus on this and result in further

sleep disruption.

The use of fitness trackers or smartphone applications which automatically calculate sleep length is not recommended

as these devices do not reliably detect time spent awake during the night and tend to overestimate total sleep time

and sleep efficiency (see: “Sleep vocabulary”).23

An example of a sleep diary template is available from:

www.goodfellowunit.org/sites/default/files/insomnia/aasm_sleep_diary.pdf

Sleep vocabulary

Sleep efficiency: |

How much time is spent asleep while trying to sleep, usually calculated as:

- Total sleep time ÷ time spent in bed × 100.

- E.g.: 5.5 hours asleep ÷ 8 hours in bed × 100 = 69%

- A sleep efficiency of ≥85% is often used as a marker of good sleep.

|

Sleep hygiene: |

Creating healthy sleep habits, such as regular times for going to bed and waking up, avoiding caffeine at night,

watching TV or using electronic devices in bed. |

Sleep latency: |

The time taken to first fall asleep |

Sleep maintenance insomnia: |

Insomnia due to waking at night and being unable to return to sleep |

Bedtime restriction, also known as sleep restriction: |

Creating limits on the time spent in bed, so that time in bed more closely matches time spent asleep. The length

of time in bed can be extended until a patient’s daytime symptoms are resolved or greatly improved. |

Help patients identify any psychological barriers to sleep

Insomnia can lead people to spend long lengths of time awake in bed, becoming frustrated at not being able to fall

asleep, or worrying about whether they will sleep properly when they go to bed. These factors can contribute to a deteriorating

cycle where concerns and anxieties over sleep make sleeping well on subsequent nights more difficult. The cognitive

aspects of CBTi focus on identifying and challenging any beliefs or attitudes the patient has about sleep that are

detrimental to their ability to sleep.

This includes addressing the following:21

- Unrealistic expectations about sleep, e.g. thinking that problems or challenges they face would easily disappear

after a good night’s sleep

- Fear of missing out on sleep. Work with patients to reduce anxieties about how they can cope and manage their day

if they do not sleep as well as they would like.

- Overestimating the consequences of poor sleep. Emphasise that many people sleep poorly or lack sleep on occasion,

and while the following day may not be pleasant, they get through okay.

Clinicians should also discuss stress associated with work or family, concerns about the future, or alcohol use which

may be interfering with sleep.

Bedtime restriction

Bedtime restriction, also known as sleep restriction, is a behavioural modification which can be added to other sleep

hygiene and lifestyle measures. A randomised controlled trial conducted in primary care in New Zealand found that adding

bedtime restriction to sleep hygiene advice resulted in improvements in patient ratings of their sleep quality, the

severity of their insomnia and their fatigue, after six months (number-needed-to-treat [NNT] of four).24

Patients can consider bedtime restriction as a way of resetting their sleep pattern in order to:

- Firstly, establish a sleeping routine and achieve as much time in bed as possible asleep, i.e. increase their “sleep

efficiency”, to reinforce the link between being in bed and sleeping

- Consolidate the amount of sleep they have into a continuous block, as this may be more restful than the same duration

of intermittent sleep

- Then, extend their sleeping duration to a length that works for them and can provide them with reliable, refreshing

sleep in the medium to long term. See the bedtime restriction guide in Table 4.

There are various approaches to bedtime restriction. The most extreme is to limit the time a patient spends in bed

to match it as closely as possible to their estimated total sleep time while they have problems with insomnia; i.e.

if a patient has been sleeping a total of six hours in interrupted blocks during the night, their time in bed is restricted

to six hours. A less extreme approach is usually more acceptable to patients, e.g. initially reducing the time spent

awake in bed by half or by more gradual reductions (Table 4). Five hours is the minimum time in

bed recommended during a bedtime restriction approach.24

Table 4: Guiding an adult patient through bedtime restriction.25

| Steps |

Instructions to patients |

Example |

1. Find out how long the patient is sleeping |

Ask patients, or use their sleep diary, to assess how much time they are actually asleep during the night

or ask for an approximation |

A patient may spend nine hours in bed, but after accounting for the time spent awake at night, only have

six hours of sleep |

2. Prescribe a new bedtime, wake up time and allowed time in bed |

Advise the patient to reduce their length of time in bed by half of the time spent awake at night, i.e. if

three hours a night are spent awake, reduce the time in bed by one and half hours.

A gradual reduction can be used if the change seems too big, e.g. going to bed 30 minutes later but getting

up at the same time.

Patients can choose a bedtime and wake up time that works for them. Getting up at the same time as other family

members or housemates can make the new routine easier to maintain. Ask patients to set an alarm for the wake up

time to develop a routine.

Five hours is the recommended minimum time in bed.

|

Since they spent three hours awake at night, the patient chooses to reduce their time in bed by one and a

half hours so in their new sleeping routine they will only spend seven and a half hours in bed per night.

They can choose how to do this, e.g. going to bed at 11:00 pm and getting up at 6:30 am, or going to bed at

midnight and getting up at 7:30 am |

3. Ask patients to stick with it for one to two weeks |

An interval of two weeks is often used to allow patients to adjust to a new sleeping pattern before deciding

whether further changes are necessary based on any ongoing symptoms.16, 24 Patients can keep a sleep

diary to track progress if they wish. |

The patient is initially more sleepy, but finds they adapt to the new schedule and after a few days begin

sleeping more continuously while in bed. |

4. Review progress and adjust timeframe as necessary |

Ask patients about their sleep, e.g.

- “How long, on average, does it take you to fall asleep?”

- “How long, on average, are you awake overnight after initially falling asleep?”

- “Are you feeling sleepy, sleep deprived, or impaired during the day because of poor sleep?”

If the patient is:

- Feeling well: keep the sleeping schedule as is

- Feeling tired: extend the time in bed by 30 minutes

- Still spending a lot of time awake at night: reduce the time in bed by 30 minutes

A goal of ≥ 85% sleep efficiency is often used, with the time in bed reduced or extended depending on the patient’s

sleep efficiency and how they feel. |

At a follow-up appointment or phone call, the patient is sleeping for six and a half out of their allotted

seven and a half hours in bed, but still has some daytime fatigue and tiredness. Their time in bed is extended

by 30 minutes and steps 3 and 4 are repeated. |

For a handout version of this table for patients, see: www.bpac.org.nz/2017/docs/insomnia-patient.pdf

Further information

A podcast on managing insomnia in primary care, presented by Professor Bruce Arroll, is available from: https://www.goodfellowunit.org/podcast/insomnia-bruce-arroll