Part 2: The ideal pharmacological approach for improving sleep

Pharmacological approaches to managing insomnia are a second-line option for adults who do not improve sufficiently with

cognitive and behavioural measures alone. For some patients with severe symptoms, medicines to help sleep can be used for a

short time initially, while non-pharmacological measures are optimised.

Also see "Part 1: Diagnosis and non-pharmacological treatment"

Key practice points:

- Medicines for improving sleep should always be used in conjunction with non-pharmacological approaches

- Patients with particularly severe symptoms or acute trouble sleeping, such as during bereavement, may benefit from

being prescribed a medicine to assist their sleep at the same time as they begin non-pharmacological treatment

- If medicines are prescribed, they should be used for a short period of time only and an “exit strategy” agreed on

from the beginning

- Benzodiazepines, zopiclone, melatonin (approved for patients aged 55 years and over) or tricyclic antidepressants

may be appropriate pharmacological options for short-term use in selected patients, depending on individual circumstances

- There is limited evidence to support the use of quetiapine for the treatment of insomnia and it is not approved for

this indication

- The majority of over-the-counter sleeping products have not been assessed in randomised controlled trials, and none,

including sedating antihistamines, are recommended in clinical guidelines.

For further information on non-pharmacological approaches for managing patients with

insomnia, see: “Part 1: Diagnosis and non-pharmacological treatment”

An ideal pharmacological sleeping aid would have:1

- A quick onset of action, so it could be taken in the evening with a predictable increase in sleepiness

- A short half-life, so it could be cleared from the body during sleep

- No or minimal ongoing effects the next day

- No potential for dependence

Not surprisingly, designing a medicine which fulfils these attributes is difficult. Sleep and wakefulness are co-ordinated

by a number of neuronal populations in different brain areas, utilising different neurotransmitters.1 Medicines

approved to improve sleep typically affect one neurotransmitter system and most medicines will have compromises in one

or more of the above characteristics. Benzodiazepines and zopiclone, for example, target the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A

receptor and induce sleep. But they have differing effects on subtypes of the receptor, do not affect other systems involved

in sleep, such as adenosine or melatonin, and can have residual effects on function the following day.1

The placebo effect provides some of the benefit of medicines for insomnia

In studies where patients with insomnia have been randomised to either a placebo medicine or no treatment, participants

taking placebo report improvements in time taken to fall asleep (sleep latency), total time spent asleep (sleep efficiency)

and sleep quality.2

Start with non-pharmacological treatment

Non-pharmacological interventions are the preferred treatment for insomnia, and should be continued even if medicines

are used.3 Beginning with this approach also helps to identify patients who are simply seeking prescriptions

for medicines such as benzodiazepines. In some cases, patients with particularly severe symptoms or acute trouble sleeping,

such as during bereavement, may benefit from being prescribed a medicine to assist their sleep at the same time as they

begin non-pharmacological treatment.

Have an exit strategy from the beginning

Clinicians should always discuss with patients the intended length of treatment when initiating medicines for insomnia,

and the plan for withdrawal. There are concerns and uncertainties regarding the safety of long-term use of medicines for

insomnia. Guidelines recommend that medicines should be used for a maximum of four weeks (but often less), with skills

learned from non-pharmacological techniques used to manage chronic insomnia over the longer term.3

There is little evidence to guide the order of prescribing; consider patient risk factors and approved indications

Few studies have directly compared the efficacy of different medicines for the treatment of insomnia.1, 3, 4 Consider

the evidence for clinical effectiveness, risks of adverse effects and approved indications before prescribing medicines

to assist sleep. A discussion of adverse effects and informed consent is required before prescribing medicines for unapproved

indications. With the exception of melatonin, lower doses of medicines used for insomnia are recommended in elderly patients

due to the risk of adverse effects such as falls.5

Hypnotic medicines should only be considered for patients with severe symptoms and used for the shortest duration possible

while patients are adopting lifestyle and behavioural changes to improve their sleep. Evidence shows hypnotic medicines,

such as short-acting benzodiazepines or zopiclone, only offer short-term benefit over and above the effects of non-pharmacological

treatment. They may produce quicker improvements in sleep for the first few weeks if prescribed at the same time as non-pharmacological

interventions are started.6, 7

Hypnotic medicines are associated with a range of adverse effects, which can include next-day “hangover” effects such

as sedation, cognitive impairment, lack of coordination, dizziness and falls,8 which also affects tasks such

as driving.1, 9 The risk of falls is also increased if patients get up during the night. Systematic reviews

and meta-analyses suggest that hypnotic medicines may not have a favourable balance of risks and benefits in older adults.1 The

American Geriatrics Society, for example, recommends that hypnotic medicines should not be a first-line choice for the

treatment of insomnia in older adults.10

Key points for consideration and discussion with patients prior to initiation

Discuss the risk of adverse effects

A discussion about adverse effects should be documented in the patient’s notes. Make sure patients are clear on when

to take their medicine, i.e. before going to bed, not if they wake during the night due to the potential for next day

sedation. Advise patients not to consume alcohol while using hypnotic medicines as this further increases the risk of

adverse effects.11

Consider the risk of interactions

Hypnotic medicines may interact with other medicines to increase the risk of adverse effects, e.g. increasing the sedative

effect. The combined use of benzodiazepines and opioids is associated with an increased risk of overdose.12

Check for potential interactions using the NZF interactions checker prior to prescribing hypnotics: www.nzf.org.nz/nzf_1

Agree on a length of treatment

Evidence shows there is no meaningful benefit of continuing a hypnotic alongside non-pharmacological approaches after

the first few weeks of treatment,6 and hypnotics do not result in better sleep in the long term. Agree on a

plan with the patient regarding the length of treatment and process of discontinuation, which may involve dose tapering

or alternate/occasional day dosing.

Hypnotic medicines are associated with tolerance and dependence

Explaining that tolerance and dependence can occur with hypnotics can help patients to understand why only a short course

of treatment is recommended. Approximately half of people who take benzodiazepines for longer than one month develop dependence,

and patients are likely to experience difficulty stopping, including symptoms such as rebound insomnia, headache, irritability

and nervousness.1, 13 Tolerance, requiring a larger dose to obtain the same benefit, and dose escalation is

possible.

If prescribed, a short-acting hypnotic should be used

The residual effects of hypnotic medicines depend on their half-life, therefore short-acting hypnotic medicines are

preferable.1 Temazepam, triazolam and zopiclone are indicated for the treatment of insomnia and have half-lives

less than 12 hours. All three of these medicines can reduce the time it takes for patients to fall asleep.4 Zopiclone

and temazepam may be more suitable for patients with problems waking during the night than triazolam.4 These

medicines should be prescribed for no more than two to three weeks,1 (but preferably for only a few nights),

and prescribed at the lowest effective dose (Table 1).5 If repeat prescriptions are given,

document the reasons for renewal in the patient’s notes.5

For further information on prescribing hypnotic medicines, see: www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2015/February/benzodiazepines.aspx

Table 1: Hypnotic medicines approved for the treatment of insomnia with half-lives less than 12 hours.

| Hypnotic medicine (alphabetical) |

Dose range5 |

Half-life 14–16 |

Temazepam  |

10 – 30 mg |

10 hours |

Triazolam  |

0.125 – 0.25 mg |

3 hours |

Zopiclone  |

3.75 – 7.5 mg |

5 hours |

* Doses in the bottom of the stated range, or lower, are recommended for elderly patients due to the risk of adverse effects such as falls5

Evidence suggests melatonin is most useful for adults who have problems sleeping due to changes or difficulties in establishing

a circadian rhythm, such as shift workers, people with jet lag, circadian rhythm disorders or those with visual impairment.17

In patients with chronic insomnia, melatonin has small effects on sleep: a seven minute reduction in sleep latency and

eight minute increase in total sleep time.18, 19 Melatonin is not as effective as a hypnotic, but may be preferable

for patients who have contraindications to, or are concerned about, the use of other medicines. Some guidelines recommend

melatonin as a first-line treatment in people aged over 55 years with insomnia due to concerns over the adverse effects

of other treatment options such as benzodiazepines.1

How does melatonin influence sleep?

Melatonin is a hormone produced by the pineal gland. Light signals from the retina suppress melatonin release, so that

in a typical circadian rhythm melatonin levels increase during the evening and peak at night.20 This pattern

of melatonin release promotes the onset and maintenance of sleep. Behavioural advice for patients with insomnia includes

avoiding bright light in the evenings, so as not to interfere with the circadian rhythm of melatonin release.

There is no known benefit of modified compared to immediate release formulations

Melatonin is available in modified release or immediate release formulations. In New Zealand, a modified release formulation

of melatonin is approved for the short-term treatment of insomnia in adults aged 55 years and over; immediate release

formulations are unapproved medicines. Both formulations are unsubsidised for the treatment of insomnia in adults.

Theoretically, immediate release formulations should provide a greater effect on the onset of sleepiness, while controlled

release formulations are better able to mimic the natural melatonin rhythm and should provide a longer duration of effect

throughout the night. However, no link between melatonin concentrations and clinical effects has been demonstrated and

modified release formulations have not been shown to be superior to immediate release formulations, or vice versa.20,21

Prescribing melatonin

Prescribe 2 mg of modified-release melatonin to be taken one to two hours prior to an appropriate bedtime*;

this dose is approved for the treatment of insomnia in patients aged 55 years and over, but unapproved for younger patients.5 Higher

doses are unapproved for patients of any age, however, clinicians could consider an increase in dose, e.g. to 3 mg, if

no effect has been obtained after one week.20

* Taking melatonin at other times could worsen problems with sleep. Shift workers may take melatonin after

a night shift in order to improve daytime sleep.

The safety of long-term use is uncertain

Clinical trials assessing the efficacy and safety of melatonin have typically been short-term, and modified-release

melatonin is indicated for the treatment of insomnia for up to 13 weeks in adults aged 55 years and over.5 In

short-term clinical trials, rates of adverse effects did not differ between patients randomised to placebo or melatonin.22,

23 The long-term effects of melatonin have not been adequately studied, due in part to melatonin being classified

as a dietary supplement in the United States rather than a medicine.24 There are concerns that melatonin could,

for example, affect the reproductive system, based on the role of melatonin in reproduction in other species.24

For further information on melatonin, see: www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2015/August/melatonin.aspx

For further information on prescribing unapproved medicines or doses, see: www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2013/March/unapproved-medicines.aspx

Some tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are associated with a sedative effect and therefore are sometimes prescribed for

the treatment of insomnia as an unapproved use, e.g. amitriptyline.1 TCAs can prevent night-time awakenings

and therefore may be useful for patients who have difficulty maintaining sleep; however, they have minimal effects on

sleep latency.4

Low doses of TCAs have not been adequately studied in clinical trials as a treatment for insomnia.1, 25 In

clinical practice, a low dose TCA, such as 10 mg amitriptyline, gradually increasing to 20 – 30 mg, may be useful for

patients with insomnia and co-morbid neuropathic pain. A TCA may also be considered in a patient with depression and insomnia.

TCAs have a greater possibility of toxicity in overdose than other medicines used for the treatment of insomnia.1 In

addition to sedation, other central nervous effects associated with TCAs include fatigue and dizziness, along with anticholinergic

effects, e.g. dry mouth, tremor, and weight gain and cardiac adverse effects, e.g. tachycardia, postural hypotension,

QT prolongation and seizures.26, 27

For further information on prescribing unapproved medicines or doses, see:

www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2013/March/unapproved-medicines.aspx

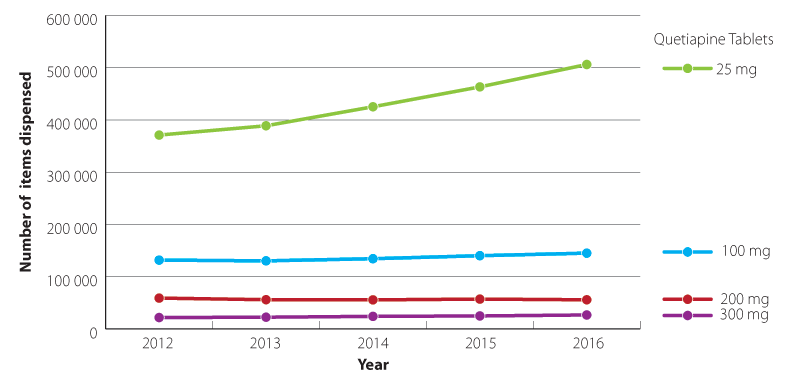

The volume of quetiapine dispensed in the community is growing, and there are concerns that it is increasingly being

prescribed off-label as a sleeping aid in low doses, e.g. ≤ 100 mg, daily (Figure 1).28, 29 This use initially

arose from its known adverse effect of causing sedation, however, systematic reviews and guidelines have found that quetiapine

has only been assessed as a treatment for insomnia in a total of 31 patients across two clinical trials.4, 30, 31 One

of these studies, which was not blinded, reported significant improvements in total sleep time and percentage of time

spent asleep; the other did not.

Quetiapine use is associated with next-day drowsiness and other long-term adverse effects

Quetiapine use is associated with a number of adverse effects. Quetiapine has a half-life of approximately seven hours,32 and

participants in clinical trials taking low dose quetiapine as a treatment for insomnia reported an increased incidence

of daytime sleepiness.30, 31 In older adults, the use of quetiapine is associated with an increased risk of

falls.33 Dry mouth is one of the most common adverse effects in the short-term.30, 31 With longer

term use, quetiapine has adverse effects on metabolic health, such as weight gain: a review of patients using low dose

quetiapine for insomnia, with most taking 100 mg, daily, found that on average patients gained 2.2 kg of weight over 11

months of treatment.31 When used at higher doses for approved indications, quetiapine has been associated with

adverse effects such as extrapyramidal symptoms, QT prolongation, and an increased risk of mortality.5, 34

Consider other options first; if used, limit use to short term and document discussions on adverse effects

Clinicians should consider whether another medicine approved for the treatment of insomnia may be more suitable than

prescribing quetiapine. If used, patients should be informed that quetiapine is not approved for the treatment of insomnia

and has the potential for adverse effects, including weight gain and other conditions associated with weight gain, such

as type 2 diabetes and obstructive sleep apnoea. The risk of these longer term adverse effects could be minimised by reducing

the duration of use to the shortest possible time frame. Discussions about these adverse effects should be documented

in the patient’s notes.

For further information on the adverse effects of quetiapine, see: www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2011/november/antipsychotics.aspx

For further information on prescribing unapproved medicines and doses, see:

www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2013/March/unapproved-medicines.aspx

Figure 1: Quetiapine formulations dispensed in the community 2012–2016 (Pharmaceutical collection, 2017).

Patients who report problems with insomnia may already have attempted to improve their sleep with over-the-counter sleep

products. However, there is little evidence to support the efficacy of most over-the-counter sleeping aids, including,

valerian, combinations of herbal remedies or vitamins, or chamomile tea (Table 2).3, 4 A

few trials have been published to suggest tart cherry products (which contain melatonin) or magnesium may be beneficial

for insomnia, however, in some of these studies the effects were not large enough to be clinically meaningful.35 Due

to the limited evidence for their effectiveness, no over-the-counter products, including sedating antihistamines are recommended

as treatments for insomnia in clinical guidelines; patients who report benefits from using these products may be experiencing

a placebo effect.1, 3, 4

Table 2: Common over-the-counter sleep products and evidence of effectiveness.

|

Evidence of clinical efficacy? |

Details |

| Vitamin and mineral supplements |

| Vitamin B |

No |

No randomised controlled trials of B vitamins for the treatment of insomnia have been conducted |

| Magnesium |

Limited |

One randomised controlled trial has been conducted in elderly participants with a low magnesium intake, which

found a decrease in the time taken to fall asleep of approximately 10 minutes and a 6% improvement in the proportion

of time spent asleep. Subjective ratings of sleep were slightly improved but not by enough to be clinically meaningful.35 |

| Herbal remedies |

| e.g. valerian, chamomile, kava, hops |

No |

Herbal remedies have either not been studied in randomised controlled trials or have been studied but are no more

effective than placebo.36 Guidelines do not recommend herbal remedies as a treatment for insomnia.3,

4 |

| Other supplements |

| Tart cherry and extracts |

Limited |

Limited clinical research suggests tart cherry, which contains melatonin, may assist with sleep. For further information,

see: www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2015/September/correspondence.aspx#2 |

| Tryptophan (5-hydroxytryptophan [5-HTP], L-tryptophan) |

No |

These have either not been studied in randomised controlled trials or have been studied but do not have clinically

significant effects on sleep.4 Guidelines do not recommend 5-HTP or L-tryptophan as treatments for insomnia.3,

4 |

| Sedating antihistamines |

| Diphenhydramine |

No |

Does not produce any meaningful improvements in total sleep duration or time taken to fall asleep.4, 5 |

| Promethazine |

Limited |

Acute effects on sleep have been shown in healthy volunteers in one study. Promethazine has a long duration of

action and can cause next-day drowsiness, and is not recommended in clinical guidelines1 |

| Products containing combinations of the above |

| E.g. Sleep drops or sleep formulas * |

No |

No randomised controlled trials of products containing combinations of herbal or flower extracts, 5-HTP or vitamin

and mineral supplements have been published. |

* Products often contain multiple ingredients, for example, a range of herbal or flower extracts

(e.g. Sleep Drops for adults, Bach Rescue sleep drops, Healtheries easy sleep tablets), or ingredients such as magnesium

and 5-HTP combined with herbal supplements (e.g. Nutralife Magnesium Complete Sleep Formula).