Antithrombotic medicines, such as aspirin and warfarin, have been routinely prescribed in primary care for decades for the prevention or treatment of arterial or venous thrombi. In 2011, we published a consensus statement on the use of antithrombotic medicines in general practice. In the last few years the indications for some oral antithrombotic medicines have expanded, e.g. dabigatran, and access to other medicines has increased, e.g. ticagrelor has been added to the Pharmaceutical Schedule. In this article we examine recent developments in the use of antithrombotic medicines, provide prescribing information for newer medicines commonly used in primary care, and update the evidence available to clinicians who are discussing the benefits and risks of antithrombotic treatment with patients.

View / Download pdf version of this article

View / Download pdf version of this article

Antithrombotic medicines in New Zealand

Antithrombotic medicines, i.e. antiplatelets and anticoagulants, have an important role in the prevention and treatment

of arterial and venous thrombi. Heparin was first isolated from liver tissue in the 1920s and since then the number of

medicines available to prevent excessive thrombosis has increased dramatically. Warfarin, the first oral anticoagulant,

was identified in the 1940s as the compound responsible for causing haemorrhage in cattle eating mouldy hay; the research

was funded by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF), hence the name “warfarin”.1 Although the analgesic

and antipyretic properties of aspirin had been known for centuries, in 1950 Dr Lawrence Craven, a general practitioner,

first published the idea that aspirin may be protective against coronary thrombosis.2 Decades later this

observation was confirmed by clinical trial.2 More recently, several novel oral anticoagulants, e.g. dabigatran,

and rivaroxaban, have been registered as medicines and guidance on their use continues to expand as more clinical trials

are conducted. Refinement of stroke risk assessment tools, e.g. CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc,

is ongoing and enables the benefits of antithrombotic treatment to be better balanced against their potential adverse

effects.

Which antithrombotic medicines are currently available for use in primary care?

Antithrombotic medicines are widely used by patients in primary care; between July 2013 and June 2014, 110 prescriptions

for either warfarin, dabigatran, clopidogrel or dipyridamole were collected from community pharmacies in New

Zealand per 1000 registered patients.3 Tables 1 and 2 show the anticoagulants and oral antiplatelet

medicines currently dispensed from community pharmacies in New Zealand, their indications and contraindications.

Can antithrombotic medicines be continued during surgical procedures?

Before patients undergo surgery it is important to balance their increased risk of bleeding, if they continue taking

an antithrombotic medicine, against their reduced risk of experiencing a thromboembolic event. This is difficult as thromboembolic

events are relatively uncommon but highly significant when they do occur, while bleeding may occur more frequently but

will often be relatively mild in comparison. The type of procedure that is being planned is an important factor when performing

this risk versus benefit analysis.

Patients taking aspirin or warfarin are highly unlikely to increase their risk of clinically significant bleeding if

they undergo routine dental procedures.4 It is also reasonable to continue aspirin or warfarin treatment

when patients undergo minor dermatological procedures in primary care; warfarin use is associated with a 1.2% increased

risk of bleeding during dermatological procedures.4 If patients are undergoing more invasive procedures in

secondary care, the decision to continue or withdraw antithrombotic treatment will be guided by the clinician performing

the procedure.

If an antithrombotic medicine is withdrawn before a surgical procedure, the timing of this withdrawal depends on the

half-life of the medicine and the patient’s renal clearance. The duration of the antithrombotic effect of aspirin and

clopidogrel is reported to be seven days and a single dose of warfarin is reported to have an antithrombotic effect for

two to five days.4 Therefore it is recommended that antiplatelet medicines be stopped seven to ten days before

the surgical procedure and warfarin five days before the surgical procedure.4

There is less data available on the bleeding risk associated with newer antithrombotic medicines, e.g. dabigatran, if

being taken by a patient undergoing a surgical procedure. In patients with a creatinine clearance (CrCl) > 50 mL/min

discontinue dabigatran 24 hours before surgery.5 If there is an increased risk of bleeding or a major surgery

is planned dabigatran should be discontinued two days before the procedure.5 In patients with a CrCl of 30

– 50 mL/min the clearance is likely to be prolonged and dabigatran should be stopped two to four days prior to the procedure.5

Managing stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation

The diagnosis of atrial fibrillation should be confirmed in primary care with a 12-lead ECG.6 Atrial fibrillation

is the cause of 20 – 25% of all ischaemic strokes and these strokes are often severe and more likely to reoccur.6 It

is therefore important to assess stroke risk in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation to determine if they are

likely to benefit from anticoagulant treatment.7 People with non-valvular atrial fibrillation have a four-

to five-fold increased risk of ischemic stroke, however, the individual risk can vary by 20-fold depending on the person’s

age and clinical features.7 People with valvular heart disease, particularly mitral stenosis, have an even

higher annual risk of embolic stroke compared to those with non-valvular atrial fibrillation, therefore adherence to anticoagulant

treatment is particularly important.

Stroke risk assessment tools

The CHADS2 stroke risk assessment tool has been widely tested in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation.7 The

CHA2DS2-VASc (Table 3) adds the categories age, vascular disease and sex to

CHADS2 and is therefore able to more reliably identify patients at very low risk who may not benefit from treatment

with an anticoagulant.6 However, both CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc may underestimate

the risk of stroke in patients with a recent transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or ischaemic stroke where other risk factors

are absent; stroke risk may be closer to 7 – 10% per year in these patients.8

The annual risk of stroke according to CHA2DS2-VASc score (calculated for a score of up to 6)

is:8

- Zero points = 0.5%

- One point = 1.5%

- Two points = 2.5%

- Three points = 5%

- Four points = 6%

- Five to six points = 7%

A number of online tools are available for calculating a patient’s CHA2DS2-VASc

score, e.g. http://clincalc.com/Cardiology/Stroke/CHADSVASC.aspx

A number of online tools are available for calculating a patient’s CHA2DS2-VASc

score, e.g. http://clincalc.com/Cardiology/Stroke/CHADSVASC.aspx

Table 3: CHA2DS2-VASc ischaemic stroke assessment tool for patients

with non-valvular atrial fibrillation7

| Clinical feature |

Score |

| Congestive heart failure |

1 |

| Hypertension |

1 |

| Age |

|

| 65 – 74 years |

1 |

| ≥ 75 years |

2 |

| Diabetes mellitus |

1 |

| Stroke or transient ischaemic attack |

2 |

| Vascular disease, e.g. peripheral artery disease, myocardial infarction, aortic plaque |

1 |

| Female sex |

1 |

| Total out of 9 = |

|

Previous guidance on the management of stroke risk has changed

Previously, patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc score

of zero were offered aspirin in preference to an anticoagulant. However, it is now recommended that these patients should

not be treated with either an anticoagulant or an antiplatelet at this time.6 Aspirin monotherapy should generally

not be prescribed for the purpose of stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation.9

Currently it is recommended that all patients with atrial fibrillation who have a CHA2DS2-VASc score

≥ 1 should be considered for anticoagulant treatment and the risks and benefits discussed with the patient.10 However,

a recent meta-analysis has suggested that the risk of ischaemic stroke in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score

of 1 may have been over-estimated and the routine treatment of these patients with an anticoagulant may not be providing

sufficient benefit to justify treatment.11 Where it is uncertain if a patient will benefit from anticoagulant

treatment a discussion with a cardiologist or neurologist may be beneficial. See The evidence: Dabigatran vs. warfarin.

The evidence: The average stroke rate in primary prevention trials for untreated patients with non-valvular

atrial fibrillation is approximately 4%, and approximately 12% in secondary prevention trials.12 Warfarin has

been used for many years to reduce the stroke risk in these patients. Adjusted-dose treatment with warfarin results in

a absolute reduction in all strokes of 2.7% per year (number needed to treat [NNT] for one year to prevent one stroke

= 37) for primary prevention, and a 8.4% reduction per year (NNT of 12) in secondary prevention.12 Treatment

with warfarin is associated with a small absolute increase in the risk of intracranial haemorrhage of 0.2% per year.12

Anticoagulants are associated with clinically significant reductions in stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation

compared to aspirin, while the risk of intracranial bleeding associated with both medicines is relatively low.12 The

Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged (BAFTA) study found that in patients aged over 75 years the annual

risk of stroke, intracranial haemorrhage and systemic embolus in patients taking warfarin was 1.8%, compared with an annual

risk of 3.8% in patients taking aspirin.13

Consider the risk of bleeding before prescribing an anticoagulant

The risk of bleeding should always be considered before discussing anticoagulation treatment with a patient, however,

it is important that the bleeding risk is not overstated. Risk factors for bleeding in patients taking anticoagulant treatment

include:10

- Increasing age

- Uncontrolled hypertension

- History of myocardial infarction, ischaemic heart disease or cerebrovascular disease

- Anaemia

- A history of bleeding

- The use of other medicines that increase bleeding risk, e.g. aspirin or other antiplatelet medicines, and non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

There are a number of tools available that can be used to assess the bleeding risk of patients with atrial fibrillation.

The HAS-BLED tool (Table 4) is relatively simple and its use is recommended in order to identify modifiable

risk factors that can be managed in patients undergoing anticoagulation treatment.6 HAS-BLED may also be useful

in balancing the risks versus benefits of anticoagulation treatment in patients with atrial fibrillation who

have a CHA2DS2-VASc score

of 1.6 However, HAS-BLED should not be used to determine whether a patient should be offered anticoagulation

treatment as this decision should be based on stroke risk estimation.6 The BAFTA study found that in patients

with a high risk of bleeding who were treated with warfarin the annual risk of intracranial haemorrhage was 0.2%; substantially

lower than the annual risk of stroke.13

A HAS-BLED score > 2 is associated with a clinically significant risk of major bleeding,7 i.e.

fatal bleeding, intracranial bleeding, or a significant drop in haemoglobin, and as a patient’s score increases there

is an increasing need for caution and monitoring when considering the use of anticoagulants.14

Percutaneous left atrial appendage occlusion is a recent intervention that is currently only available privately in

New Zealand but is likely to be a option in the future for patients in whom anticoagulation is not tolerated or is contraindicated.9

Table 4: HAS-BLED bleeding risk prediction tool7

| Risk factor |

Score |

| Hypertension (systolic blood pressure > 160 mmHg) |

1 |

| Abnormal renal and liver function |

1 point each |

| Stroke (past history) |

1 |

| Bleeding (previous history of bleeding or predisposition to bleeding) |

1 |

| Labile INRs (unstable, high or insufficient time with therapeutic range) |

1 |

| Elderly (aged over 65 years) |

1 |

| Drugs or alcohol (including concomitant use of aspirin, other antiplatelet medicines and NSAIDs) |

1 point each |

| Total out of 9 = |

|

Deciding between warfarin or dabigatran to prevent thromboembolism

Once it has been decided that anticoagulant treatment is appropriate, it is necessary for patients and their general

practitioners to decide whether warfarin or dabigatran is the preferred treatment option. The decision to initiate other

anticoagulants, e.g. rivaroxaban, will be made in secondary care.

The advantages of dabigatran compared to warfarin include:

- Superior ability to prevent stroke when dabigatran 150 mg, is taken twice daily

- Testing of level of anticoagulation and dose adjustments are not currently required, although research into a suitable

monitoring test is underway

- Onset of anticoagulation is rapid (two to three hours) compared with 48 – 72 hours with warfarin15

- Does not accumulate in the liver and therefore safer than warfarin in patients with hepatic dysfunction16

- Fewer interactions with other medicines and foods

- A reduced risk of intracranial haemorrhage when dabigatran 110 mg, is taken twice daily

The disadvantages of dabigatran compared with warfarin include:

- An increased incidence of gastrointestinal adverse effects, e.g. dyspepsia

- Twice daily dosing required

- Caution is required in patients with progressive chronic kidney disease (CKD)

- There is no reversal agent to prevent or treat haemorrhage

- A small absolute increase in risk (0.27%) of acute coronary syndrome17

Patient preference plays a significant role in determining whether warfarin or dabigatran is the most appropriate treatment

choice. Some patients may feel more comfortable initiating treatment with warfarin as it has a long history of being relatively

safe when the dose is adjusted appropriately. Patients may also be reassured by the regular INR testing when taking warfarin

and the fact that the anticoagulant effects can be reversed with vitamin K. Patients with established cardiovascular disease

may also prefer warfarin as the use of dabigatran is associated with a small increase in risk of myocardial infarction

or acute coronary syndrome.17 The increased “health time” that patients taking warfarin have with health professionals

due to INR testing may be beneficial, particularly for patients who live alone. Alternatively, other patients may prefer

a newer medicine and the reduced risk of intracranial haemorrhage associated with dabigatran use. Patients and clinicians

are likely to find dabigatran more convenient than warfarin because there is no need to perform monitoring to assess anticoagulation.

Some patients may benefit from taking an anticoagulant and an antiplatelet, e.g. patients with atrial fibrillation following

an acute coronary syndrome.18 However, when a patient who is taking an anticoagulant is prescribed an antiplatelet

their risk of bleeding is increased by approximately 50%.18 Therefore a lower dose of dabigatran, i.e. dabigatran

110 mg, twice daily, may be preferable in patients also taking an antiplatelet, due to the decreased risk of major bleeding

with the lower dabigatran dose.18 However, this must also be balanced against the small increased risk of acute

coronary syndrome in patients taking dabigatran.

In patients with valvular heart disease and atrial fibrillation warfarin is the preferred anticoagulant; treatment with

dabigatran is contraindicated in this situation (see below).

On balance the evidence suggests that dabigatran is at least as effective and may be safer than warfarin for the prevention

of ischaemic stroke and systemic embolism.

See: “The evidence: Dabigatran vs. warfarin”.

See: “The evidence: Dabigatran vs. warfarin”.

Dabigatran should NOT be prescribed to patients with valvular heart disease

Dabigatran is not indicated for the prevention of thrombosis in patients with mechanical heart valves and should not

be prescribed for this indication. There is evidence that patients with mechanical heart valves who take dabigatran are

at an increased risk of bleeding or experiencing a thromboembolic event compared to what their risk would have been if

they had been prescribed warfarin. Several trials comparing the efficacy and safety of warfarin or dabigatran in patients

who had undergone heart valve replacement were stopped early prompting the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to

release a statement that the use of dabigatran as a anticoagulant is contraindicated in patients with mechanical heart

valves.19

The evidence: Evidence that dabigatran should not be used in patients with mechanical heart valves

comes from a study that was stopped early due to an excess of bleeding and thromboembolic events in patients taking dabigatran.20 Of

the 252 patients enrolled in the study who had undergone mitral-valve replacement, 168 received treatment with dabigatran

and 84 received warfarin.20 Dabigatran dosing was at 150 mg, 220 mg or 300 mg, twice daily, depending on renal

function.21 Ischaemic or unspecified stroke occurred in 5% of patients taking dabigatran but did not occur

in any patients taking warfarin, and major bleeding occurred in 4% of patients taking dabigatran and 2% of patients taking

warfarin.20

Initiating dabigatran treatment

Dabigatran is rapidly and completely converted to its active metabolite when taken orally. Approximately 80 – 85% of

the dose is excreted in the urine therefore dose reduction is appropriate in people with renal impairment.22 Renal

function should be assessed before prescribing dabigatran. In patients with a creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min

dabigatran is contraindicated (see NZF for details).15 Dosing

regimens for the various indications of dabigatran are shown in Table 5, below. Patients aged over 80 years with atrial

fibrillation should be prescribed the lower dose of dabigatran 110 mg, twice daily, due to the increased risk of bleeding

in this patient group.15 Regular monitoring of renal function is also recommended for patients taking dabigatran

(Table 1).

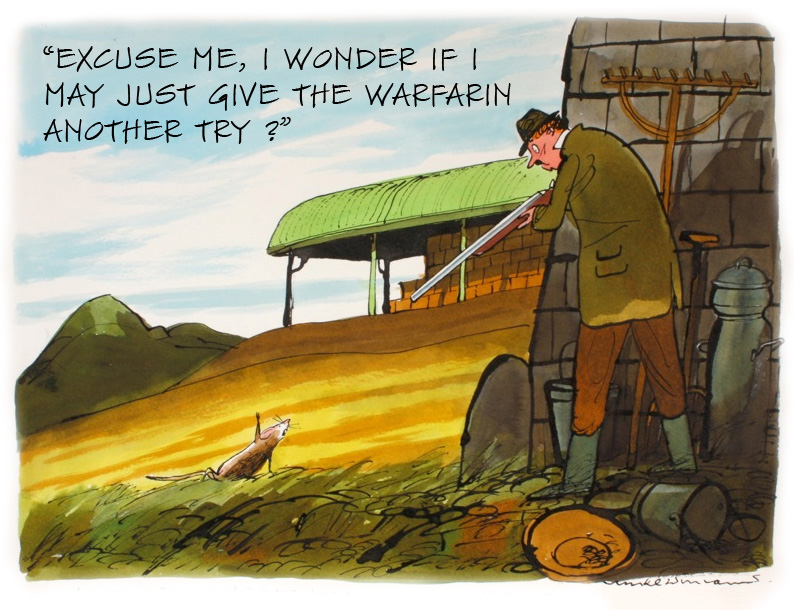

Reprinted with kind permission from Mike Williams

The evidence: dabigatran vs. warfarin

The effectiveness and safety of dabigatran in reducing stroke risk in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation

was largely established by the Randomised Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation therapy (RE-LY) trial. This trial enrolled

over 18 000 patients with atrial fibrillation who were treated with either 110 mg dabigatran, twice daily, or 150 mg dabigatran,

twice daily, or adjusted-dose warfarin.21 It was concluded that in patients with atrial fibrillation, 110

mg of dabigatran, twice daily, was associated with rates of stroke and systemic embolism comparable to warfarin treatment,

but lower rates of major haemorrhage.21 Therefore dabigatran 110 mg, twice daily is recommended for patients

aged over 80 years in whom a reduced bleeding risk is preferable.15 Patients treated with dabigatran 150

mg, twice daily, had a lower risk of stroke and thromboembolism compared with warfarin with a comparable risk of major

haemorrhage.21

After one to three years, almost half of the patients in the RE-LY trial were enrolled in the Long-term Multicenter

Extension of Dabigatran Treatment in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation (RELY-ABLE) trial which had a mean follow-up of

4.3 years.23 The risk of major bleeding and intracranial haemorrhage in patients taking dabigatran was similar

to that of the RE-LY trial, although there was no control group of patients taking warfarin enrolled to confirm these

findings.23 The 150 mg, twice daily, dose of dabigatran continued to be associated with an increased rate

of major bleeding compared with the 110 mg, twice daily, dose.23

A 2013 subgroup analysis of the RE-LY trial has found that the reported benefits of dabigatran in terms of stroke and

systemic embolism prevention compared to warfarin are also seen in patients who are concurrently taking an antiplatelet

medicine.18 The dabigatran 110 mg, twice daily dose was associated with a lower risk of major bleeding than

adjusted-dose warfarin; the dabigatran 150 mg, twice daily, dose was associated with the same risk of major bleeding as

warfarin.18 However, the stroke and embolism preventing effects of dabigatran 150 mg, twice daily, did appear

to be somewhat reduced by the concurrent use of an antiplatelet.18

The available evidence does not, however, completely support dabigatran in preference to warfarin. Recently a different

group of investigators performed a retrospective study of patients diagnosed with atrial fibrillation to assess the risk

of bleeding in 1302 patients taking dabigatran and 8102 patients taking warfarin.24 Compared to warfarin,

dabigatran treatment (dose not recorded) was found to be associated with an increased risk of major bleeding (regardless

of anatomical location) and gastrointestinal bleeding, but a lower risk of intracranial haemorrhage.24

A trial of over 2500 patients with acute venous thromboembolism compared dabigatran 150 mg, twice daily, with dose-adjusted

warfarin. It was found that dabigatran treatment for patients with venous thromboembolism was associated with significantly

fewer clinically relevant bleeds or bleeds of any sort and that dabigatran was associated with a trend towards fewer major

bleeds.25 Contrary to studies in other patient groups the rate of intracranial bleeding was the same in both

groups of patients; there were two intracranial bleeds recorded in each group of patients.25

Ticagrelor is superior to clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes

It is increasingly likely that patients who have been diagnosed with an acute coronary syndrome will be treated with

ticagrelor, twice daily, in preference to clopidogrel, once daily; both are used in combination with aspirin, i.e. dual

antiplatelet treatment. This treatment is particularly beneficial to patients following a coronary stenting procedure

as stent thrombosis is often fatal. The choice of anticoagulant is usually made in hospital following diagnosis of an

acute coronary syndrome and treatment is then continued in the community for twelve months. In patients who are likely

to experience issues with compliance the once daily dosing regimen of clopidogrel may be seen as an advantage over twice

daily treatment with ticagrelor.

Ticagrelor is a direct-acting and reversible antagonist of the P2Y12 receptor found on platelets and causes

rapid inhibition of platelet activation and aggregation.16 Clopidogrel also acts to inhibit platelet aggregation

by irreversibly blocking the P2Y12 receptor; the irreversible inhibition of clopidogrel can be an advantage

in patients where treatment compliance is an issue.16 Unlike clopidogrel, ticagrelor is not a prodrug and therefore

does not need to be processed by an enzyme (CYP2C19) to be activated. This explains why ticagrelor is reported to produce

faster, greater and more consistent inhibition of platelet reactivity compared with clopidogrel.26 Evidence

supporting the preferential use of ticagrelor over clopidogrel for patients with an acute coronary syndrome with or without

a prior history of stroke or TIA is accumulating.26, 27

See: “The evidence: Ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel”.

See: “The evidence: Ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel”.

Table 5: Dosing regimens for indications of dabigatran use in New Zealand15

| Indication |

Dose |

Duration |

| Prophylaxis of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation |

Dabigatran, 150 mg, twice daily OR dabigatran, 110 mg, twice daily in patients aged over 80 years |

Ongoing |

| Treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism |

Dabigatran, 150 mg, twice daily, after at least five days of parenteral anticoagulant treatment |

Continued for up to six months |

| Prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism following major joint surgery |

Dabigatran, 110 mg, one to four hours after surgery, then dabigatran 220 mg, once daily |

For ten days following knee surgery and 28 – 35 days following hip surgery |

For further information, see:

“Dabigatran revisited”, BPJ 50 (Feb, 2013).

For further information, see:

“Dabigatran revisited”, BPJ 50 (Feb, 2013).

Ticagrelor may be more effective than clopidogrel in Māori or Pacific peoples

Research has identified genetic polymorphisms in the CYP2C19 enzyme that metabolises clopidogrel, which may influence

treatment efficacy. Ethnic differences have also been found in the prevalence of these alleles. A study of 312 New Zealand

patients with acute coronary syndrome treated with clopidogrel and aspirin found that 47% of Māori and Pacific peoples

had a loss-of-function CYP2CI9 allele, while 11% had a gain-of-function CYP2C19 allele.28 In comparison 26%

of Europeans with acute coronary syndrome had a loss-of-function allele and 41% had a gain-of-function allele.28 The

authors were also able to correlate the presence of the loss-of-function CYP2C19 allele with increased levels of platelet

reactivity on assay from patients taking clopidogrel.28 High platelet reactivity levels have been associated

with poorer outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. The authors of the study concluded that Māori and Pacific

peoples should be preferentially treated with ticagrelor over clopidogrel.28

Although the clinical implications of the research are not yet fully known, to date no genetic variations in the efficacy

of ticagrelor have been reported. Therefore this is a further reason why many cardiologists recommend ticagrelor in preference

to clopidogrel for the treatment of patients with an acute coronary syndrome.

How is ticagrelor initiated?

Treatment with ticagrelor begins with 180 mg as a single dose, then 90 mg, twice daily, for up to 12 months.15 It

should be taken in combination with low-dose aspirin, e.g. 100 mg, daily.15 The most frequent adverse effect

associated with the use of ticagrelor is a transient dyspnoea that does not appear to be caused by bronchospasm. For this

reason, ticagrelor should be used cautiously in patients with asthma or COPD.15 Ticagrelor should be discontinued

five days before elective surgery.15 It is recommended that renal function be tested within one month of initiation

of ticagrelor.15 Patients aged over 75 years, those who have moderate or severe renal impairment, and those

taking an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) may be more likely to have an increase in creatinine levels.29 Ticagrelor

should be used cautiously in patients with a history of hyperuricaemia or gout. The use of ticagrelor is not recommended

in patients with uric acid nephropathy.29

For further information, see: “Ticagrelor

– out with the old and in with the new?”, BPJ 54 (Aug, 2013).

For further information, see: “Ticagrelor

– out with the old and in with the new?”, BPJ 54 (Aug, 2013).

The evidence: ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel

The Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial compared ticagrelor versus clopidogrel for the prevention

of cardiovascular events in more than 18 000 patients admitted to hospital with an acute coronary syndrome, with or without

ST segment elevation.26 All patients received aspirin 75 – 100 mg daily, unless they could not tolerate aspirin.26 Compared

with clopidogrel, ticagrelor was found to significantly reduce mortality from vascular causes, myocardial infarction,

or stroke, without increasing the overall rate of major bleeding, although, an increase in bleeding not related to coronary-artery

bypass grafting was seen in patients taking ticagrelor.26

A recent subgroup analysis of 11 080 patients with non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome from the PLATO trial

randomised to either ticagrelor or clopidogrel found that ticagrelor significantly reduced the rates of death from vascular

causes, myocardial infarction, or stroke without an increase in the rate of overall bleeding.26 After 12

months, the rates of death from these causes was 9.8% in patients taking ticagrelor and 11.7% in those taking clopidogrel.26 However,

ticagrelor was associated with an increased rate of bleeding not related to surgery, including more instances of fatal

intracranial bleeding.26

Patients with acute coronary syndrome and a prior history of stroke or TIA have a mortality rate twice that of patients

with acute coronary syndrome without a history of stroke or TIA.27 These patients are also at three times

the risk of experiencing a stroke and four times the risk of having an intracranial bleed compared with patients without

a history of stroke or TIA.27 The assessment of the benefits and risks of treatment with an antiplatelet

are difficult in this context as many of the factors that indicate high ischaemic risk also suggest an elevated risk of

bleeding, e.g. age, hypertension, diabetes.27 In the PLATO trial, 1152 patients with acute coronary syndrome

had a history of stroke or TIA and subgroup analysis found that the benefits of ticagrelor treatment were also applicable

in this high-risk patient group.27 However, this net clinical benefit in patients with a history of cerebrovascular

disease has been challenged by some clinicians.30

Table 1: Anticoagulant medicines currently available from community pharmacies in New Zealand15

| Anticoagulant |

Indications |

Contraindications |

Comments |

Warfarin

vitamin K antagonist |

Prevention of thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) with at least one risk factor, e.g. previous

TIA or stroke, systemic embolism, symptomatic heart failure, age ≥ 75 years, age ≥ 65 years with coronary artery disease,

hypertension, or diabetes.

Prevention of stroke following myocardial infarction in patients with increased embolic risk.

Prevention and treatment of venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Prevention of thromboembolism in patients with prosthetic heart valves. |

Haemorrhagic stroke, active bleeding or significant risk of major bleeding.

Should not be used during pregnancy or within 48 hours postpartum. |

Dose is adjusted according to the patient’s INR; the patient should spend more than 65% of the time in the therapeutic

range.6 For primary and secondary prevention of stroke the dose is adjusted to achieve an INR of 2–3.

In patients with aortic valve prosthesis the target INR is 2.5–3.0, and in patients with mitral valve prosthesis the

INR target is 3.0–3.5.

For further information, see: “Use of INR for monitoring warfarin treatment”, BT (Nov, 2010).

For further information, see: “Use of INR for monitoring warfarin treatment”, BT (Nov, 2010).

Medicines are available to reverse the anticoagulant effect of warfarin, e.g. vitamin K.

Fully subsidised without restrictions. |

Dabigatran

direct thrombin inhibitor |

The prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular AF with at least one risk factor,

e.g. previous TIA or stroke, systemic embolism, symptomatic heart failure, age ≥ 75 years, age ≥ 65 years with coronary

artery disease, hypertension, or diabetes.

Prevention of venous thromboembolism following total hip or knee replacement.

Treatment of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism after at least five days of parenteral anticoagulant treatment

(new 2014).

Prevention of recurrent deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism (new 2014). |

Active bleeding or significant risk of major bleeding.

Should not be used as an anticoagulant in patients with prosthetic heart valves.

Should not be used in patients with CrCl < 30 mL/min.

Concomitant treatment with ketoconazole.5 |

Regular monitoring of renal function is required. Test renal function in all patients prior to initiation and

preferably three to six monthly (but at least annually) in patients with a CrCl of 30 – 50 mL/min.

Test renal function annually in patients aged over 75 years and in all patients where there may be a decline in renal

function, e.g. dehydration or diuretic use.5

Currently no reversal medicine is available.

Therapeutic testing may be available in the future to improve treatment efficacy, although this would negate one

of the benefits of treatment.

Fully subsidised without restrictions. |

Rivaroxaban

inhibitor of factor Xa |

The prevention of venous thromboembolism following a total hip or knee replacement.

Treatment of deep vein thrombosis.

Prevention of recurrent deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular AF and at least one risk factor: symptomatic

heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years, diabetes, or prior TIA or stroke. |

Active bleeding or significant risk of major bleeding, prosthetic heart valve.

Hepatic disease associated with coagulopathy.31 |

Check renal function before prescribing; doses in patients with renal impairment may need to be reduced (or the

medicine avoided) depending on the indication (see NZF for details).

Fully subsidised with Special Authority approval for up to five weeks following a hip replacement and up to two weeks

following a knee replacement with application from any relevant practitioner. |

Apixaban

inhibitor of factor Xa |

The prevention of venous thromboembolism following hip or knee replacement surgery.

The prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular AF and at least one risk factor: symptomatic

heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years, diabetes, or prior TIA or stroke. |

Active bleeding or significant risk of major bleeding. |

Check renal function before prescribing; doses in patients with renal impairment may need to be reduced (or the

medicine avoided) depending on the indication (see NZF for details).

Efficacy not established in patients with prosthetic heart valves.

This medicine is approved for use but not currently subsidised. |

Enoxaparin

low molecular weight heparin - LMWH |

The prevention of deep-vein thrombosis in surgical and medical patients.

Treatment of deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Treatment of acute coronary syndromes.

Prevention of clotting in haemodialysis.

Treatment of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy (unapproved indication). |

Haemorrhagic disorders, thrombocytopenia, recent cerebral haemorrhage, severe hypertension, peptic ulcer, major

trauma or recent surgery to the eye or nervous system, acute bacterial endocarditis, spinal or epidural anaesthesia

with treatment doses of unfractionated or LMWH, hypersensitivity to unfractionated or LMWH. |

The risk of bleeding may be increased if renal function is impaired; reduce dose if eGFR is < 30 mL/min/1.73m2.

Monitoring anti-factor Xa may be required in patients with an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73m2 and unfractionated

heparin may be preferable.

Immune-mediated thrombocytopenia can develop after five to ten days. Platelets should be measured before treatment

and monitored if given for longer than four days.

Hyperkalaemia can result from inhibition of aldosterone in patients with: diabetes, renal failure, acidosis, or raised

plasma potassium. |

For further information on anticoagulants, including initiating warfarin treatment, reversing the effects of

anticoagulants, and converting between anticoagulants see:

http://files.www.clotconnect.org/healthcare-professionals/resources-for-health-care-professionals/AnticoagPocketGuide-1.pdf

For further information on anticoagulants, including initiating warfarin treatment, reversing the effects of

anticoagulants, and converting between anticoagulants see:

http://files.www.clotconnect.org/healthcare-professionals/resources-for-health-care-professionals/AnticoagPocketGuide-1.pdf

N.B. The dosing regimens and indications in the above link are based on current United

States guidance and may not always be applicable to the New Zealand context.

Table 2: Oral antiplatelet medicines currently available from community pharmacies in New Zealand15

| Antiplatelet |

Indications |

Contraindications |

Comments |

Aspirin

salicylate non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

The prevention of thrombotic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease.

For use in patients following coronary artery by-pass surgery.

For the treatment of acute thrombotic conditions, e.g. acute myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke. |

Previous or active peptic ulcer, haemophilia, severe cardiac failure.

A history of hypersensitivity to aspirin or NSAIDs.

Not for the treatment of gout. |

Guidelines vary for the use of aspirin in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Generally, aspirin can

be considered for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with a five-year cardiovascular risk > 20%

and without significant risk factors for bleeding.32

Fully subsidised without restrictions. |

Clopidogrel

thienopyridine antiplatelet |

The prevention of vascular ischaemic events in patients with symptomatic atherosclerosis.

The prevention of atherothrombotic events in patients with acute coronary syndrome for up to 12 months (with aspirin). |

Severe hepatic impairment, active bleeding or significant risk of major bleeding. |

Clopidogrel has the benefit over aspirin of not requiring concomitant gastroprotection in patients with previous

peptic ulceration, when taken as monotherapy.

Following an acute coronary syndrome a flag can be placed in the patient’s notes to remind clinicians when the treatment

period has finished.

Fully subsidised without restrictions. |

Dipyridamole

adenosine reuptake and phosphodiesterase inhibitor |

The secondary prevention of ischaemic stroke or TIA.

The prevention of thromboembolism in patients with prosthetic heart valves (with aspirin). |

Nil |

Should be used cautiously in patients with rapidly worsening angina, aortic stenosis, recent MI, left ventricular

outflow obstruction, heart failure, hypotension, myasthenia gravis. Migraine may be exacerbated.

Fully subsidised without restrictions. |

Ticagrelor

reversible purinoreceptor-P2Y12 antagonist |

The prevention of atherothrombotic events in patients with acute coronary syndrome for up to 12 months (with aspirin) |

Active bleeding or significant risk of major bleeding, history of intracranial haemorrhage. |

Measure renal function one month after initiation. Should be used with caution in patients with asthma or COPD,

or in patients with a history of hyperuricaemia.

A flag can be placed in the patient’s notes to remind clinicians when the treatment period has finished.

Fully subsidised with Special Authority approval following application by any relevant practitioner for patients

recently diagnosed with a ST-elevation or non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome and in who fibrinolytic treatment

has not be given in the last 24 hours (and is not planned to be given). |

Prasugrel

thienopyridine antiplatelet |

The prevention of atherothrombotic events in patients with acute coronary syndrome who are undergoing percutaneous

coronary intervention. |

Active bleeding or significant risk of major bleeding, history of TIA or stroke. |

Discontinue at least seven days before surgery depending on the clinical circumstance.

Fully subsidised with Special Authority approval for patients who have undergone coronary angioplasty in the past

four weeks and have a bare metal stent or a drug-eluting stent, and are clopidogrel-allergic i.e. a history of anaphylaxis,

urticaria, generalised rash, or unexplained asthma developing shortly after clopidogrel initiation. Subsidy also applies

for patients who have had a stent thrombosis while taking clopidogrel. |

Acknowledgement

Thank you to Associate Professor Stewart Mann, Head of Department and Associate Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine,

Department of Medicine, University of Otago, Wellington, Dr Ian Rosemergy, Consultant Neurologist, Capital & Coast DHB and

Associate Professor Gerry Wilkins, Associate Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine, Dunedin School of Medicine, University

of Otago for expert review of this article.

References

- Wardrop D, Keeling D. The story of the discovery of heparin and warfarin. Br J Haematol 2008;141:757–63.

- Miner J, Hoffhines A. The discovery of aspirin’s antithrombotic effects. Tex Heart Inst J 2007;34:179–86.

- Ministry of Health (MOH). Pharmaceutical Claims Collection. MOH, 2015.

- Armstrong MJ, Gronseth G, Anderson DC, et al. Summary of evidence-based guideline: Periprocedural management of antithrombotic

medications in patients with ischemic cerebrovascular disease: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the

American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2013;80:2065–9.

- Boehringer Ingelheim Ltd. New Zealand datasheet: PRADAXA dabigatran etexilate. 2014. Available from:

www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/datasheet/p/Pradaxacap.pdf (Accessed Apr, 2015).

- Hobbs FR, Taylor CJ, Jan Geersing G, et al. European Primary Care Cardiovascular Society (EPCCS) consensus guidance

on stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation (SPAF) in primary care. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2015;Epub (Ahead of print).

- Meschia JF, Bushnell C, Boden-Albala B, et al. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a statement for healthcare

professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke J Cereb Circ 2014;45:3754–832.

- Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient

ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association.

Stroke 2014;45:2160–236.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Atrial fibrillation: the management of atrial fibrillation.

NICE, 2014. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg180 (Accessed Apr, 2015).

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. Available

from: www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/AF_publication.pdf (Accessed Apr, 2015).

- Friberg L, Skeppholm M, Terént A. Benefit of anticoagulation unlikely in patients with atrial fibrillation and a

CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:225–32.

- Hart R, Pearce L, Aguilar M. Meta-analysis: Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular

atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:857–67.

- Mant J, Hobbs FDR, Fletcher K, et al. Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population

with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study, BAFTA): a randomised controlled

trial. Lancet 2007;370:493–503.

- Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, et al. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding

in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest 2010;138:1093–100.

- New Zealand Formulary (NZF). NZF v34. 2015. Available from: www.nzf.org.nz (Accessed Apr, 2015).

- Weitz J. Antiplatelet, anticoagulant, and fibrinolytic drugs. In: Harrision’s principles of internal medicine. McGraw

Hill Medical, 2012. pp. 988–1004.

- Uchino K, Hernadez A. Dabigatran association with higher risk of acute coronary events: meta-analysis of noninferiority

randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:397–402.

- Dans AL, Connolly SJ, Wallentin L, et al. Concomitant use of antiplatelet therapy with dabigatran or warfarin in

the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) trial. Circulation 2013;127:634–40.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA Drug safety communication: Pradaxa (dabigtran etexilate mesylate) should

not be used in patients with mechanical prosthetic heart valves. FDA, 2012. Available from:

www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm332912.htm (Accessed Apr, 2015).

- Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Brueckmann M, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valves.

N Engl J Med 2013;369:1206–14.

- Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. 2009;361:1139–51.

- Brayfield A. Martindale: The complete drug reference. 2014th ed. Pharmaceuctical Press, 2014. Available from:

www.medicinescomplete.com (Accessed Apr, 2015).

- Connolly SJ, Wallentin L, Ezekowitz MD, et al. The long-term multicenter observational study of dabigatran treatment

in patients with atrial fibrillation (RELY-ABLE) study. Circulation 2013;128:237–43.

- Hernandez I, Baik SH, Piñera A, et al. Risk of bleeding with dabigatran in atrial fibrillation. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:18–24.

- Schulman S, Kakkar AK, Goldhaber SZ, et al. Treatment of acute venous thromboembolism with dabigatran or warfarin

and pooled analysis. Circulation 2014;129:764–72.

- Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes.

N Engl J Med 2009;361:1045–57.

- James SK, Storey RF, Khurmi NS, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes and

a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. Circulation 2012;125:2914–21.

- Larsen P, Johnston L, Holley A, et al. Prevalence and significance of CYP2C19*2 and CYP2C19*17 alleles in a New Zealand

acute coronary syndrome population: CYP2C19*2 in acute coronary syndromes. Intern Med J 2015;Epub (Ahead of print).

- Astra Zeneca Ltd. Medicine data sheet: Brilinta. 2012. Available from:

www.medsafe.govt.nz (Accessed Apr, 2015).

- DiNicolantonio JJ, Serebruany VL. Comparing ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with a history of cerebrovascular

disease: A net clinical harm? Stroke 2012;43:3409–10.

- Bayer New Zealand Ltd. Data sheet: XARELTO rivaroxaban. 2014. Available from:

www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/datasheet/x/Xareltotab.pdf (Accessed

Apr, 2015).

- Cardiovascular disease risk assessment: updated 2013 - New Zealand Primary Care Handbook 2012. 2013. Available from:

www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/cardiovascular-disease-risk-assessment-updated-2013-dec13.pdf (Accessed Apr, 2015).