Published: January, 2025 | Review date: January, 2028

Recommendations for heart failure treatment have changed over time due to the availability of new classes of medicines such as angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs) and other treatments, e.g. sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors. This audit helps primary healthcare professionals ensure patients diagnosed with heart failure are receiving optimal care.

Once heart failure has been diagnosed, pharmacological treatment needs to be initiated as soon as practically possible to improve patient outcomes. Given that most clinical trial evidence regarding effective management relates to patients with HFrEF, it is practical to initiate treatment in primary care assuming they have this subtype, and then refine management once echocardiology findings become available, if needed.

In New Zealand primary care, the conventional approach for pharmacological management in patients with HFrEF has been somewhat conservative, involving sequential treatment escalation in response to symptoms (Figure 1A). However, the approach to management has transformed considerably in recent years based on mounting evidence from numerous large clinical trials. International guidelines are increasingly recommending that most patients with heart failure should be promptly established on four guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) medicines and up-titrated to the highest tolerated or target dose, unless contraindicated (Figure 1A).1, 2

GDMT includes treatment with:

- An ARNI (preferred) or an ACE inhibitor/ARB if this is not possible; and

- A beta blocker (either bisoprolol, metoprolol succinate or carvedilol); and

- A mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA); and

- A SGLT-2 inhibitor

GDMT maximises prognostic outcomes (e.g. risk of hospitalisation and mortality) and limits disease progression (Figure 1B).3 Treatment can be initiated and optimised based on a clinical diagnosis of heart failure in primary care (i.e. there is no need to wait for echocardiography); the approach to management can be refined later, if required, once echocardiogram results are available. In addition to GDMT, assertive treatment with a loop diuretic is required if the patient has fluid overload.

For further information on identifying and diagnosing patients with heart failure in primary care, see: bpac.org.nz/2025/heart-failure-part-2.aspx

Figure 1. An overview of (A) guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) or an undifferentiated clinical diagnosis (i.e. echocardiography results are not yet available) and (B) the benefits of GDMT versus other treatment regimens in patients with HFrEF.1-4

N.B. HFrEF refers to patients with symptoms and signs of heart failure and a LVEF ≤ 40% confirmed by echocardiography. Previous definitions for HFrEF have also encompassed the LVEF range 41 – 49%, but this is now distinguished as being heart failure with a mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF); the management approach for HFrEF and HFmrEF are largely the same.

The logistics of GDMT use are still being refined

Establishing patients on GDMT requires the introduction of multiple medicines, overlapping titration schedules, as well as broad monitoring and tolerance considerations. The evidence base is rapidly evolving, and patient characteristics and co-morbidities can differ considerably, meaning a standardised approach will not work in every scenario.

General considerations for GDMT use include:4

- Simultaneous versus sequential introduction – simultaneous initiation of GDMT medicines and subsequent up-titration yields the best outcomes but requires close monitoring, potentially limiting suitability outside of hospital/inpatient settings. As such, rapid sequential addition is a reasonable approach in primary care.

- Prompt optimisation is best – aim to introduce and achieve optimal dosing within three months in a community setting. Rapid GDMT optimisation is preferrable, where possible. If any GDMT medicines are already being taken, or patients initially require hospitalisation, an abridged timeline should be targeted (e.g. six weeks or less), assuming close monitoring is possible.

- Introducing multiple medicine classes should be prioritised – the ideal scenario is that patients should receive all four GDMT medicines up-titrated to the target dose. However, if this is not possible due to specific clinical circumstances, using lower doses of multiple medicine classes is preferable over high doses of one or two medicines. This approach helps to address the diverse maladaptive pathways and multi-system dysfunction associated with heart failure.

A focus on the “newer” medicines for heart failure

Primary care clinicians are experienced in the use of traditional heart failure medicines such as ACE inhibitors/ARBs, beta blockers and MRAs. However, it is important they also familiarise themselves with the “newer” heart failure medicines and prioritise their use in the absence of contraindications; heart failure is a progressive condition and the best prognostic outlook is achieved when patients are taking all four components of GDMT.

ARNI (sacubitril + valsartan)

An ARNI combines a neprilysin inhibitor and an ARB, delivering a dual mechanism of action. Sacubitril + valsartan (Entresto) is the only ARNI currently available. ARNIs were first validated in the PARADIGM-HF trial, where sacubitril + valsartan reduced the absolute risk of cardiovascular death or hospitalisation by almost 5% compared with enalapril in patients with symptomatic heart failure also taking a beta blocker (NNT = 21). Subsequent investigations showed that ARNIs also improve markers of cardiac function such as left ventricular function (systolic and diastolic), BNP concentrations, burden of ventricular arrhythmias, as well as other clinical endpoints, e.g. quality of life, duration of hospitalisation required.

There is a growing consensus that immediate or early ARNI use should be prioritised for RAAS inhibition in patients with HFrEF where possible, including in patients already stabilised on an ACE inhibitor/ARB.1 However, Special Authority restrictions in New Zealand for ARNIs mean that ACE inhibitors/ARBs are still often the first step for RAAS inhibition (see below).

As of January, 2025, Special Authority criteria for funded access to sacubitril with valsartan in New Zealand requires that the patient:

Has heart failure

and

Is in NYHA/WHO functional class II, III or IV

and

Has a documented LVEF ≤ 35%

or

An echocardiogram is not reasonably practical, and in the opinion of the treating practitioner the patient would benefit from treatment

and

Is receiving concomitant optimal standard chronic heart failure treatment

The timing of a transition between ACE inhibitor/ARB and ARNI treatment will differ depending on individual clinical circumstances, and whether they are already established on these medicines for treating co-morbidities, e.g. hypertension. If transitioning between these treatments, the ARNI can be initiated:

- At least 24 hours after the last dose of ARB, i.e. same time, following day, when the next dose would have been due

- At least 36 hours after the last dose of ACE inhibitor due to the elevated risk of angioedema (see the NZF monograph for further information)

SGLT-2 inhibitor (empagliflozin)

Previously, the SGLT-2 inhibitor empagliflozin was only funded for patients with type 2 diabetes who met eligibility criteria. However, from 1st December, 2024, funded access has been widened to include patients with HFrEF due to evidence that SGLT-2 inhibitors significantly improve prognostic outcomes in patients with heart failure regardless of diabetes status, and also protect against the progression of proteinuric renal dysfunction in patients with chronic kidney disease (which is common in this setting).

The empagliflozin Special Authority criteria are similar to sacubitril + valsartan (above), however, the LVEF threshold is slightly more lenient; patients must have an LVEF ≤ 40% (or an echocardiogram is not reasonably practical, and in the opinion of the treating practitioner the patient would benefit from treatment). N.B. Patients with echocardiography-confirmed HFpEF not already established on a SGLT-2 inhibitor may wish to consider self-funding treatment, but this will be a barrier to access for some patients.

References

- Maddox TM, Januzzi JL, Allen LA, et al. 2024 ACC Expert consensus decision pathway for treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2024;83:1444–88. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.12.024

- Kittleson MM, Panjrath GS, Amancherla K, et al. 2023 ACC Expert consensus decision pathway on management of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2023;81:1835–78. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.03.393

- Tromp J, Ouwerkerk W, Van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. A systematic review and network meta-analysis of pharmacological treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JACC: Heart Failure 2022;10:73–84. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2021.09.004

- Carrizales-Sepúlveda EF, Ordaz-Farías A, Vargas-Mendoza JA, et al. Initiation and up-titration of guideline-directed medical therapy for patients with heart failure: better, faster, stronger! Card Fail Rev 2024;10:e03. doi:10.15420/cfr.2023.20

Summary

This audit identifies patients who have been diagnosed with heart failure for at least three months, and either have HFrEF or an undifferentiated clinical diagnosis, to determine if their treatment regimen remains appropriate or whether they may benefit from further treatment optimisation, i.e. to align with current GDMT recommendations. This audit does not focus on patients with confirmed HFpEF as management differs and should ideally be directed by cardiology guidance.

A three-month minimum timeframe was selected for the purposes of this audit to encompass a reasonable treatment initiation and up-titration period. In general, up-titration of most* GDMT medicines can occur approximately every two weeks in primary care, up to the maximum tolerated or recommended target dose. However, this schedule may differ depending on individual patient characteristics and circumstances, monitoring capacity, and whether medicines are being up-titrated in a staggered or overlapping manner.

* SGLT-2 inhibitors are taken at one specified dose in patients with heart failure without the need for up-titration

Recommended audit standards

Most patients with heart failure should be established on the four GDMT medicines and up-titrated to the highest tolerated or target dose, unless:

- There are contraindications to one or more of the medicines

- There is a clinical justification in their notes for why treatment escalation is not appropriate based on their specific circumstances

- They do not meet the criteria for Special Authority approval for sacubitril + valsartan (ARNI) and/or empagliflozin (SGLT-2 inhibitor)

If these criteria are not met, the patient should be flagged for review to determine the appropriate next step(s), depending on their clinical circumstances. This may include deciding whether:

- Dose increases for current medicines are warranted, e.g. dose of an ACE inhibitor/ARB or beta blocker has not yet been up-titrated

- The patient should switch to an ARNI (and stop the ACE inhibitor/ARB). For further information on ARNI initiation and monitoring considerations, see: nzf.org.nz/nzf_70779

- Other GDMT medicine(s) should be introduced, e.g. MRA (e.g. spironolactone) or SGLT-2 inhibitor

- Cardiology advice or referral is required

Eligible patients

All patients who have been diagnosed with heart failure for at least three months and are identified as having either HFrEF or an undifferentiated clinical diagnosis (i.e. echocardiography has not yet been performed) are eligible for this audit. Patients with HFpEF can be excluded.

Identifying patients

You will need to have a system in place that allows you to identify eligible patients. Many practices will be able to identify patients by running a “query” through their PMS, initially searching for all patients with heart failure. The clinical notes of identified patients will need to be reviewed to ascertain the duration and type of heart failure (to confirm eligibility) as well as treatment details, including their current regimen and symptom status (to determine audit outcome).

Sample size

The number of eligible patients will vary according to your practice demographic, and for some practices the initial query may return a large number of results. If this occurs, a sample size of 20 – 30 patients is sufficient for this audit.

N.B. The principles of this audit should still be considered opportunistically in any consultation involving a patient with heart failure.

Criteria for a positive outcome

A positive outcome is achieved if an eligible patient is established on the four GDMT medicines at the highest tolerated or target dose, or there is a documented reason why this has not occurred.

Data analysis

Use the sheet provided to record your data. The percentage achievement can be calculated by dividing the number of patients with a positive outcome by the total number of patients audited.

Patients who do not meet the criteria for a positive result should be flagged for clinical review to consider how treatment can be optimised (see: “Recommended audit standards”).

This publication was supported by an unrestricted educational grant by Novartis NZ Ltd. The publication was independently written and Novartis had no control over the content. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of Novartis

Clinical audits can be an important tool to identify where gaps exist between expected and actual performance. Once completed, they can provide ideas on how to change practice and improve patient outcomes. General practitioners are encouraged to discuss the suitability and relevance of their proposed audit with their practice or peer group prior to commencement to ensure the relevance of the audit. Outcomes of the audit should also be discussed with the practice or peer group; this may be recorded as a learning activity reflection if suitable.

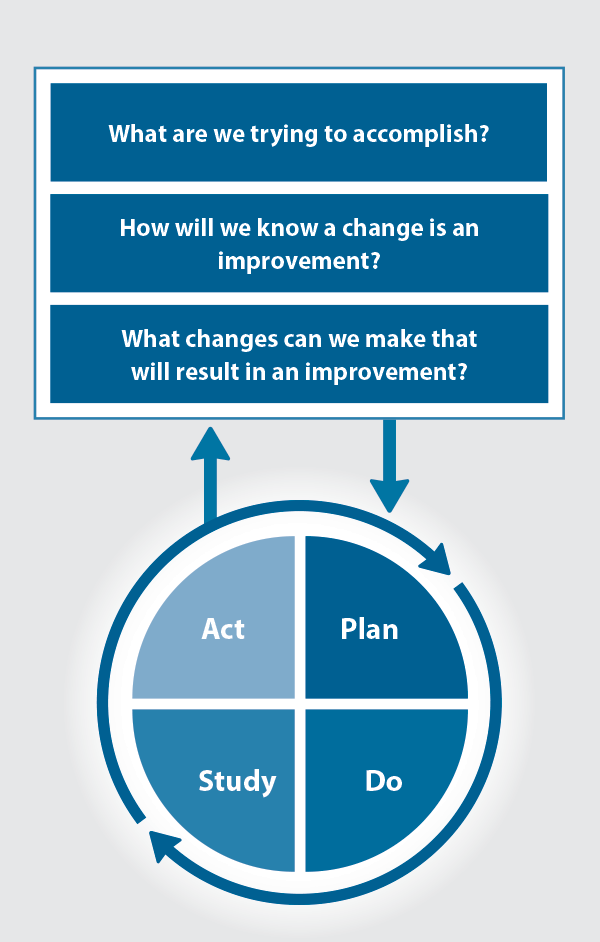

The Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) model is recommended by the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners (RNZCGP) as a framework for assessing whether a clinical audit is relevant to your practice. This model has been widely used in healthcare settings since 2000. It consists of two parts, the framework and the PDSA cycle itself, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The PDSA model for improvement.

Source: Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycles and the model for improvement

1. The framework

This consists of three questions that help define the “what” and “how” of an improvement project (in this case an audit).

The questions are:

- "What are we trying to accomplish?" – the aim

- "How will we know that a change is an improvement?" – what measures of success will be used?

- "What changes can we make that will result in improvement?" – the concept to be tested

2. The PDSA cycle

This is often referred to as the “engine” for creating, testing and carrying out the proposed changes. More than one cycle is usually required; each one is intended to be short, rapid and frequent, with the results used to inform and refine the next. This allows an ongoing process of continuous learning and improvement.

Each PDSA cycle includes four stages:

- Plan – decide what the change to be tested is and how this will be done

- Do – carry out the plan and collect the data

- Study – analyse the data, assess the impact of the change and reflect on what was learned

- Act – plan the next cycle or implement the changes from your plan

Claiming credits for Te Whanake CPD programme requirements

Practice or clinical audits are useful tools for improving clinical practice and credits can be claimed towards the Patient Outcomes (Improving Patient Care and Health Outcomes) learning category of the Te Whanake CPD programme, on a two credit per learning hour basis. A minimum of 12 credits is required in the Patient Outcomes category over a triennium (three years).

Any data driven activity that assesses the outcomes and quality of general practice work can be used to gain credits in the Patient Outcomes learning category. Under the refreshed Te Whanake CPD programme, audits are not compulsory and the RNZCGP also no longer requires that clinical audits are approved prior to use. The college recommends the PDSA format for developing and checking the relevance of a clinical audit.

To claim points go to the RNZCGP website: www.rnzcgp.org.nz

If a clinical audit is completed as part of Te Whanake requirements, the RNZCGP continues to encourage that evidence of participation in the audit be attached to your recorded activity. Evidence can include:

- A summary of the data collected

- An Audit of Medical Practice (CQI) Activity summary sheet (Appendix 1 in this audit or available on the

RNZCGP website).

N.B. Audits can also be completed by other health professionals working in primary care (particularly prescribers), if relevant. Check with your accrediting authority as to documentation requirements.