Use of PPIs in New Zealand

The treatment of symptoms caused by gastric acid dates backs to the ancient Greeks, who used coral powder (calcium carbonate)

to alleviate dyspepsia.1 During the 1970s and ‘80s H2-receptor antagonists, e.g. ranitidine, were introduced.

This was followed by the introduction of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which were even more effective in reducing gastric

acid production. PPIs have now largely superseded H2-receptor antagonists, resulting in an improved quality of life for

many patients. Their effectiveness, however, has also led to PPIs being used more widely in primary care than almost any

other medicine.

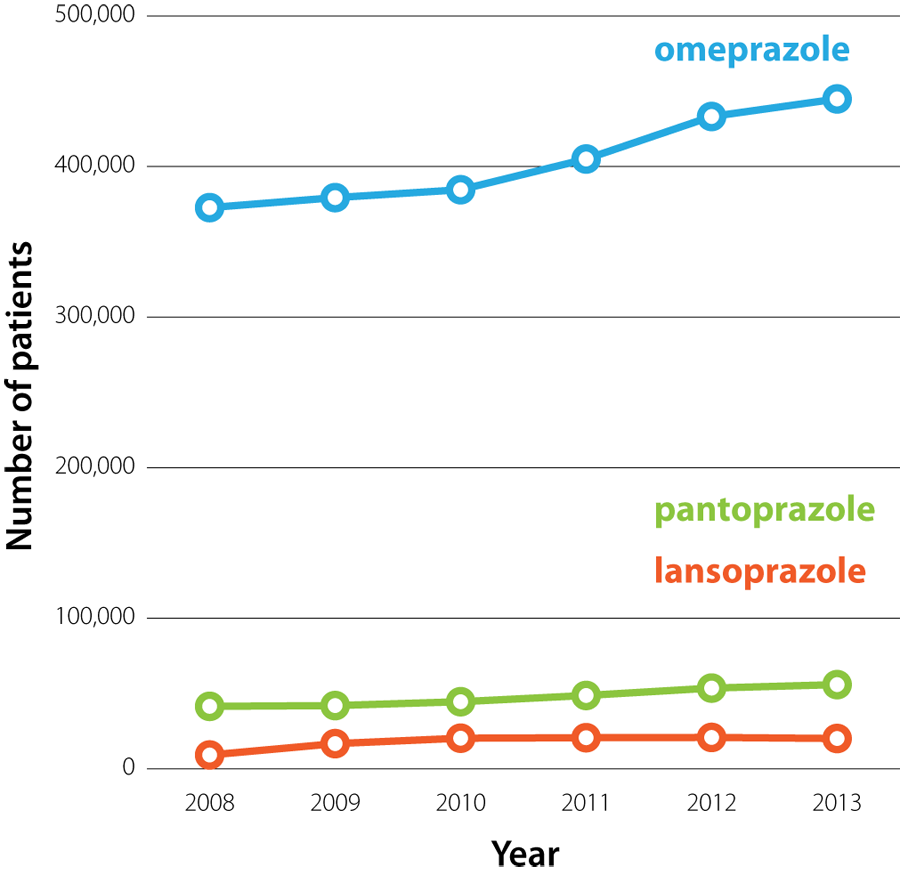

In 2013, there were 428 dispensed prescriptions for omeprazole for every 1000 registered patients, making it the third

most widely prescribed medicine in New Zealand.2 The number of patients prescribed PPIs in New Zealand has

increased steadily over the past five years (Figure 1). In 2013, $4.28 million was spent in the New

Zealand health sector on omeprazole capsules alone; over one-quarter of this was for omeprazole 40 mg capsules, the highest

dose formulation available.3

Which PPIs are available in New Zealand?

In New Zealand there are three fully subsidised PPIs available on the Pharmaceutical Schedule: omeprazole, lansoprazole

and pantoprazole. These three medicines are also available for purchase in limited quantities, without prescription, as

a “Pharmacy only” medicine. Rabeprazole is available unsubsidised, with a prescription. Patients should be asked about

any use of non-prescription medicines before acid suppressive medicines are prescribed.

Refer to the New Zealand Formulary for further details on these medicines:

www.nzf.org.nz

Refer to the New Zealand Formulary for further details on these medicines:

www.nzf.org.nz

Omeprazole, lansoprazole and pantoprazole are indicated for:4

|

Figure 1: The number

of patients who were dispensed omeprazole, pantoprazole or lansoprazole from a community pharmacy in New Zealand (2008

– 2013).3 |

- Treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), including Barrett’s oesophagus

- Prevention of NSAID-associated duodenal or gastric ulcers (omeprazole and pantoprazole only)

- Treatment of benign duodenal and gastric ulcers

- Eradication of Helicobacter pylori (as part of a combination regimen with antibiotics)

- Treatment of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (omeprazole and pantoprazole only)

The PPIs available in New Zealand have a similar efficacy when given at recommended doses; e.g. a meta-analysis found

there was no difference in the comparative effectiveness of PPIs in healing oesophagitis.5 The availability

of three subsidised PPIs means that if a patient experiences adverse effects with one PPI, another can be trialled. It

also allows for choices in formulation, e.g. pantoprazole is available in small tablets that may be preferable for patients

who have difficulty swallowing.

When, and how, is it appropriate to prescribe a proton pump inhibitor?

When initiating PPI treatment it is helpful to discuss with patients what the expected duration of treatment is likely

to be. This reinforces the message that treatment will not continue indefinitely, unless the indication remains, and is

likely to make later discussions about dose adjustment and treatment withdrawal easier.

For most patients an appropriate starting regimen is omeprazole 20 mg, once daily (depending on the indication).4 In

some patients, treatment may need to be increased to 40 mg, daily, if symptoms are not able to be controlled, but starting

treatment initially with omeprazole 40 mg, once daily, is rarely indicated in a primary care setting. Over time, and again

depending on the indication for treatment, the dose of PPI may be able to be reduced, e.g. from 20 mg to 10 mg omeprazole,

daily, or changed to “as needed” dosing, if adequate control of symptoms is achieved.

N.B. Before prescribing a PPI it is important to consider a patient’s risk factors for gastric cancer, as PPI use can

mask the symptoms of this malignancy. The incidence of gastric cancer increases substantially after age 55 years, and

a decade earlier in people of Māori, Pacific or Asian descent.7

The pharmacology of proton pump inhibitors

PPIs are prodrugs, i.e. they are inactive when administered and undergo conversion to an active form in vivo.6 PPIs

are acid labile and are therefore formulated with an enteric coating to protect them from degradation in the acidic environment

of the stomach. Once they have passed through the stomach and the enteric coating has dissolved in the small intestine,

PPIs are absorbed into the blood where they have a relatively short plasma half-life of 1 – 1.5 hours.1 The effect of

PPIs extends well beyond this half-life, because the active metabolite binds irreversibly to the H+/K+-ATPase proton pump

of parietal cells. This prevents the transport of acidic hydrogen ions into the gut lumen for 10 – 14 hours.6 The acid-suppressing

effect of PPIs takes at least five days to reach a maximal effect.1 However, this effect is not absolute; even at high

doses approximately one-quarter of proton pumps in each parietal cell will remain active.6

Gastrin is the hormone that stimulates parietal cells to release gastric acid. When PPI inhibition of gastric acid production

occurs, gastrin release is increased to compensate for the decreased acidity of the stomach. Recently, several

studies have suggested that when PPIs are withdrawn the body will continue to produce gastrin at above pre-treatment

levels, causing an effect referred to as rebound acid secretion.6

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

Proton pump inhibitors are indicated in the treatment of suspected or confirmed GORD. The treatment regimen depends

on the severity of symptoms and the likelihood of the patient developing complications. PPIs can be used to:1, 8

- Establish a diagnosis of GORD via empiric treatment over several weeks

- Provide “as needed” relief of symptoms in patients with milder forms of GORD

- Provide daily symptom relief for patients with more severe symptoms

When managing patients with mild GORD, it is important that the patient and clinician both agree that the regimen will

be regularly reviewed, with the goal of treatment being lifestyle control of symptoms with minimal reliance on medicines.

The lowest effective dose of PPI should be used for the shortest possible time.

For further information, see: “Update on the

management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease”.

For further information, see: “Update on the

management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease”.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-associated ulcers

PPIs are indicated for the prevention and treatment of NSAID-induced erosions and ulcers in at risk patients (see below),

and are often prescribed to treat NSAID-induced dyspepsia.4 PPIs should be taken daily, rather than “as needed”,

to prevent NSAID-related adverse effects because ulceration or bleeding of the gastrointestinal tract can occur in the

absence of dyspepsia.9

Risk factors for gastrointestinal adverse effects, e.g. perforations, ulcers and bleeding, associated with NSAID use

include:9, 10

- Age over 65 years

- Previous adverse reaction to NSAIDs

- The use of other medicines that may exacerbate any gastrointestinal adverse effects, e.g. anticoagulants, antiplatelets

and corticosteroids

- A history of cardiovascular disease

- Liver disease

- Chronic kidney disease

- Smoking

- Excessive alcohol consumption

Many of these risk factors are also contraindications to the use of NSAIDs.

A PPI is appropriate for patients with any of the above risk factors, who are taking NSAIDs long-term. Patients should

be advised to report any gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. heartburn, black stools) which may indicate that an erosion or

ulcer has occurred.9 Also consider checking the patient’s haemoglobin level after one month of NSAID treatment.9

For ulcer prevention, the recommended regimen is omeprazole 20 mg, once daily, for the duration of NSAID treatment.4 To

treat NSAID-associated duodenal or gastric ulcers the recommended regimen is omeprazole 20 mg, once daily, for four weeks,

which may be continued for a further four weeks if required.4 Pantoprazole is an alternative in both regimens

if omeprazole is not tolerated.4 Lansoprazole is not indicated for ulcer prevention in patients taking NSAIDs,

but can be used for treatment of ulcers.4

For further information see: “Non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Making safer treatment choices”, BPJ 55 (Oct, 2013).

For further information see: “Non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Making safer treatment choices”, BPJ 55 (Oct, 2013).

Eradication treatment for H. pylori

Proton pump inhibitors are recommended for the eradication of H. pylori as part of a triple treatment regimen. For example,

a seven day course of:4

- Omeprazole 20 mg, twice daily; and

- Clarithromycin 500 mg, twice daily; and

- Amoxicillin 1 g, twice daily (or metronidazole 400 mg, twice daily, if allergic to penicillin)

Other regimens using different dosing intervals or other PPIs, e.g. lansoprazole, can also be used (see NZF

for further information).

Confirmation of eradication of H. pylori after a triple treatment regimen is not required for the majority of patients.

A test of cure may be considered in patients with a recurrence of symptoms, a peptic ulcer complication or those with

important co-morbidities.11

For further information, see: “The changing

face of Helicobacter pylori testing”, BT (May, 2014).

For further information, see: “The changing

face of Helicobacter pylori testing”, BT (May, 2014).

When can you consider stopping treatment with a PPI?

Many patients taking PPIs require long-term treatment and withdrawal of the PPI will be inappropriate, e.g. patients

with Barrett’s oesophagus. In other patients, e.g. with a history of severe erosive oesophagitis, withdrawal of PPIs should

only be considered after discussion with an appropriate specialist. However, in each practice population there will be

some patients for whom it is appropriate to reduce the dose of the PPI they are prescribed, e.g. from 20 mg omeprazole,

once daily, to 10 mg omeprazole, once daily, or switching to “as needed” dosing. For patients taking PPIs long-term the

need for ongoing treatment should be reassessed at every consultation.

The patient’s expectations when the PPI was first prescribed will play a large part in their acceptance of the suggestion

to reduce their PPI exposure. There is no clear evidence as to what the best regimen for withdrawing PPI treatment is,

but in general, downward dose titration should be considered when symptoms are under control.6 For example, a patient

is prescribed 20 mg omeprazole, daily, for four to six weeks to manage symptoms of GORD. The patient responds to treatment

and their symptoms resolve. The dose is then reduced to 10 mg, daily, for two weeks, and then treatment is stopped. The

patient is given a prescription for 20 mg omeprazole to use “as needed” if symptoms return.

Advise patients about the possibility of rebound acid secretion

Rebound acid secretion can occur when PPIs are withdrawn; one study found that more than 40% of asymptomatic patients

experienced dyspepsia one week after completing a four week treatment course of pantoprazole.12 Serum markers suggest

that acid secretion one week following cessation of PPI treatment can be significantly increased above pre-treatment levels.

This should return to normal within two weeks.12

The symptoms caused by rebound acid secretion, e.g. gastro-oesophageal reflux, are the same as those that would be an

indication for PPI treatment, therefore a reinforcing loop can be formed where initial treatment creates the need for

further treatment. The possibility of rebound acid secretion should be discussed with patients so they can be prepared

for this when withdrawing from PPI treatment.

Medicines that contain both an antacid and an anti-foaming agent, e.g. Mylanta P oral liquid, Acidex oral liquid, Gaviscon

Double Strength tablets are likely to be the most effective treatment for rebound acid secretion. Aluminium hydroxide

tablets can also be effective. Any of these products can be prescribed as “rescue” medication and provide reassurance

to patients if symptoms return.

For further information see: “Managing gastro-oesophageal

reflux disease (GORD): an update”.

For further information see: “Managing gastro-oesophageal

reflux disease (GORD): an update”.

How safe are proton pump inhibitors?

The rate of adverse effects associated with PPI treatment is relatively low. However, given that each practice is likely

to have many patients taking PPIs, clinicians need to be aware of the potential risks. These risks should be discussed

with patients, and the need for periodic monitoring considered in those at increased risk.

All three subsidised PPIs available in New Zealand can cause headache and gastrointestinal adverse effects, e.g. nausea,

vomiting abdominal pain, flatulence, diarrhoea or constipation.4 The gastrointestinal adverse effects of PPIs

can be mistaken for symptoms of GORD, sometimes resulting in increased doses of PPI being prescribed. Less frequently,

PPI use is associated with dry mouth, peripheral oedema, dizziness, sleep disturbances, fatigue, paraesthesia, arthalgia,

myalgia, rash, pruritus and interstitial nephritis.4

PPIs are not known to be associated with an increased risk of foetal malformations in humans (Pregnancy Risk Category

B3).4 PPIs are therefore considered safe to use during pregnancy, however, other medicines should be used

where possible. A reasonable approach for pregnant women who require acid suppressive medication is to trial antacids

(e.g. calcium carbonate, alginate formulations) or ranitidine (Pregnancy Risk Category B1) first and if these medicines

are not effective, consider prescribing a PPI.

Higher doses of PPIs should be avoided in patients with moderate to severe liver disease because decreased metabolism

may cause the medicine to accumulate (see NZF for details).4

The risk of infection is increased

Gastric acid suppression with PPIs increases the risk of infection with gastrointestinal or respiratory pathogens, although

the absolute risk to most patients remains low. The higher risk is thought to be due to a reduction in the effectiveness

of the “acid wall” stomach barrier. This allows viable pathogens to travel up or down the gastrointestinal tract and also

colonise the lower airways.

Where possible, consider delaying the initiation of PPIs in patients with an increased risk of infection, e.g. an older

patient with a family member who has influenza, patients who are taking antibiotics or travelling to countries where there

is a high risk of enteric infection.6 It is not known if there is any benefit to temporarily stopping treatment

in patients who are already taking PPIs, during periods when they are at an increased risk of infection.

In a meta-analysis of 12 studies involving almost 3 000 patients, it was found that acid-suppressing treatment increased

the risk of C. difficile infection. This risk was increased 1.7 times with once-daily PPI use and 2.4 times with more

than once daily use.13 Six studies found a greater than three-fold increased risk of Salmonella, Campylobacter

and Shigella infection in patients taking PPIs.13

In another study of over 360 000 people, it was found that PPI use was associated with an increased risk of pneumonia,

and the risk increased with increasing dose of PPI.14 The incidence rate of pneumonia in people taking a PPI

was 2.45 per 100 person-years, compared to 0.6 per 100 person-years in people not taking a PPI.14 Another

study found that the likelihood of patients developing pneumonia was increased five-fold during the first week of PPI

treatment, but decreased after this, falling to 1.3-fold increased risk after patients had been treated for three months

or more.15 This effect may be explained by patients presenting with the early symptoms of pneumonia being

prescribed a PPI.6

Malabsorption of nutrients may occur

Acid in the gut increases the solubility of elements, e.g. calcium and iron, from insoluble salts and makes protein-bound

vitamins, e.g. vitamin B12, available for absorption. It has therefore been suggested that gastric acid suppression may

decrease absorption of some nutrients and lead to an increased prevalence of conditions related to malabsorption. However,

this association is controversial. In most cases, patients can be reassured that a balanced diet, including essential

elements and minerals (e.g. calcium, iron, folate, magnesium) is adequate to address this risk.

Long-term PPI use has been associated with a small increase in fracture risk. However, the New Zealand

Medicines Adverse Reactions Committee (MARC) noted that the association between PPI use and fracture risk in the majority

of studies was modest and does not warrant any regulatory action at this time.16 A study of more than 15 000

instances of osteoporosis-related fractures found that after five years of PPI use patients had an increased risk of hip

fracture (adjusted odds ratio = 1.62), and the risk increased further when treatment was continued for seven years (adjusted

odds ratio = 4.55).17 Patients taking PPIs for more than seven years also had an increased risk of non-hip

fractures (adjusted odds ratio = 1.92).17

An increased risk of osteoporosis should be considered in post-menopausal females who are taking PPIs long-term, especially

if they have other risk factors, e.g. a family history of osteoporosis or long-term corticosteroid use. Stepping down

PPI treatment to the lowest effective dose, or prescribing “as needed” treatment, if appropriate, may reduce this risk.

Severe hypomagnesaemia has been associated with the use of PPIs, in a limited number of patients, which

resolved when PPI treatment was withdrawn.18 In 2012, Medsafe advised that hypomagnesaemia, and possibly hypocalcaemia,

were rare adverse effects of PPI use. Omeprazole, 20 – 40 mg per day, was the dosage most frequently associated with these

deficiencies.19 Magnesium is known to affect calcium homeostasis by deceasing parathyroid hormone secretion

and decreasing the response of the kidney and the skeleton to parathyroid hormone.19

Patients with a history of excessive alcohol use, who are taking a PPI, have an increased risk of developing hypomagnesaemia

due to the additive effects of chronic ethanol exposure on metabolic function. The use of diuretics, ciclosporin or aminoglycosides

with PPIs increases the risk of hypomagnesaemia occurring. Symptoms of hypomagnesaemia are non-specific and may include

muscle cramps, weakness, irritability or confusion.

Routine testing of magnesium levels in patients taking PPIs is generally not recommended. However, if a patient has

been taking a PPI long-term and they present with unexplained symptoms that are consistent with hypomagnesaemia, consider

requesting a serum magnesium level. Increased dietary intake of magnesium rich foods, e.g. nuts, spinach or wheat, or

magnesium supplementation may be sufficient to improve serum magnesium levels while continuing the PPI. For some patients

the PPI will need to be stopped; if the indication for using the PPI is strong, a re-challenge while monitoring magnesium

can be undertaken.

For further information see: “Hypomagnesaemia

with proton pump inhibitors” BPJ 52 (Apr, 2013).

For further information see: “Hypomagnesaemia

with proton pump inhibitors” BPJ 52 (Apr, 2013).

Vitamin B12 deficiency has been associated with the use of PPIs in older patients.18 Several short-term

studies have shown that PPIs decreased the absorption of vitamin B12 from food.18 In older patients with poor

nutrition, who are taking PPIs long-term, consider testing vitamin B12 levels periodically.18

Hyponatraemia has been associated with the use of PPIs in a very small number of patients.20 Hyponatraemia,

however, is a relatively common occurrence in older people, many of whom are likely to be taking PPIs.

Acute interstitial nephritis has been associated with PPIs

Prior to June 2011, the Centre for Adverse Reactions Monitoring (CARM) had received 65 notifications of interstitial

nephritis linked to PPI use.21 Interstitial nephritis can result in permanent kidney damage.6 Symptoms and

signs suggestive of interstitial nephritis include: fever, rash, eosinophilia, malaise, myalgia, arthralgia, weight loss,

altered urine output, haematuria or pyuria and/or high blood pressure.21 NSAIDs are well known for their nephrotoxic

potential and their use should increase suspicion of interstitial nephritis in patients with these symptoms. Other risk

factors that would increase the suspicion of interstitial nephritis include the use of β-lactams, e.g. penicillins or

cephalosporins, sulphonamides and diuretics, or the presence of infection or immune and neoplastic disorders.21 If

interstitial nephritis is suspected, request urine microscopy and renal function tests. The patient should be referred

to a Nephrologist for assessment. To confirm a diagnosis of interstitial nephritis a renal biopsy is required.

Interactions with other medicines

Concerns of a possible interaction between omeprazole and clopidogrel are unlikely to be clinically significant.

MARC assessed the evidence of an interaction between PPIs and clopidogrel and concluded that while there was evidence

that PPIs may affect clopidogrel activity ex vivo, the available evidence suggested that this would not translate to clinically

significant adverse outcomes.22 There is no need to switch treatment for patients who are already taking a

PPI and clopidogrel. However, if considering prescribing a PPI at the same time as clopidogrel then pantoprazole is the

recommended choice. Pantoprazole is known to have less of an inhibitory effect on the CYP2C19 enzyme compared with omeprazole

or lansoprazole.23

PPIs can cause a minor increase in the anticoagulant effect of warfarin or a decrease when the PPI

is stopped. Patients taking warfarin should have their INR measured more frequently following the initiation, or discontinuation

of PPIs to ensure they do not experience a clinically significant interaction.8