Successful treatment of long-term pain includes keeping patients active and engaged in their daily life.

Establish specific goals

Develop goals of care with the patient that are relevant to the patient and achievable, e.g. being able to walk the

dog by the next consultation.

Non-pharmacological approaches to reducing pain

Discuss “sleep hygiene” techniques with patients who have disturbed sleep. This emphasises reserving the bed and bedroom

for sleeping and sex. Advise patients to avoid watching television or using electronic devices in the bedroom and to leave

the room if they are awake for longer than 15 minutes, returning only when tired enough to sleep. Other advice includes

avoiding stimulants or diuretics, including alcohol close to bed-time and keeping a regular sleep routine, even during

weekends.

Tricyclic antidepressants, taken in the evening, may provide the dual benefit of pain relief and sedation overnight

(see: “The pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain”).

For further information on sleep hygiene, see: “Managing

insomnia”, BPJ 14 (Jun, 2008)

For further information on sleep hygiene, see: “Managing

insomnia”, BPJ 14 (Jun, 2008)

Staying active and engaged is a priority

If patients withdraw from their normal activities, discuss the reasons and consider whether any medicines require alteration.

Some patients may benefit from consultation with an occupational therapist, physiotherapist or counsellor. Patients with

low activity levels may benefit from supervised exercise or a Green Prescription.

Persistent pain is a strong risk factor for falls in older patients; exercise improves strength and balance.19 Improving

mobility to maintain independence and social participation will be a goal of care for many patients.

Planning can help patients fulfil their usual activities

People with long-term pain often tire quickly. Suggest patients devote time to important tasks early in the day or when

they have the most energy; this may led to a greater sense of control over their condition.

Support groups help patients connect and learn from others

Advice and information for patients about how to manage and live with long-term pain is available from:

Consider if support devices are necessary

Some patients may benefit from assistive devices, such as toilet and shower rails. Occupational therapists may be able

to organise subsidised installations of these supports for select patients. Patients at risk of falls may benefit from

a medical alarm.

Other non-pharmacological approaches have limited evidence of efficacy

Interventions such as acupuncture or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) may be useful for patients who

have ongoing pain despite medication.20 There have been few clinical trials, however, assessing their efficacy

or comparing their effects with pharmacological treatments.

Psychological approaches, such as cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), may help patients adapt to living with pain,

however, there is little evidence to suggest they reduce neuropathic pain.

The pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain

The medicines recommended for the initial treatment of neuropathic pain include (see Table 2 for

dosing):1, 21

- TCAs, such as amitriptyline and nortriptyline – fully subsidised, unapproved indication. Amitriptyline is the TCA

with the strongest evidence of effectiveness and is favoured in some international guidelines.1, 21 However,

nortriptyline has less anticholinergic activity than amitriptyline and less adverse effects in elderly patients.22,

23

- Gabapentin – fully subsidised with Special Authority approval for patients diagnosed with neuropathic pain.

The related medicine pregabalin has a similar efficacy and adverse effect profile as gabapentin, and is available

unsubsidised. Be mindful that co-administration of morphine can increase levels of gabapentin and dosing

may need to be adjusted.24

- Carbamazepine – initial treatment for patients with trigeminal neuralgia or diabetic polyneuropathy; fully subsidised.

These medicines have evidence of efficacy and are first or second-line treatments for neuropathic pain;21, 25 guidelines

do not favour one initial medicine over another.1, 21 For most neuropathic pain medicine efficacy is not dependent

on the underlying cause, therefore, potential adverse effects may dictate the choice of treatment, e.g. patients with

central neuropathic pain may be less tolerant of medicines with CNS adverse effects.21 The patient’s need for

analgesia may fluctuate and regular follow-up is important. For patients with central-post stroke pain there is evidence

that medicines are less effective.26

Tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentin, either alone or in combination, and carbamazepine (for trigeminal neuralgia and

diabetic neuropathy) are appropriate options for treating most types of neuropathic pain in primary care. Alternative

anticonvulsant medicines, e.g. valproate or lamotrigine may be trialled in primary care, however, there is limited evidence

of effectiveness in patients with neuropathic pain.

The role of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is unclear. NSAIDs are not included as treatment

options in neuropathic pain guidelines.1, 27 However, there is insufficient evidence to conclude that they

are ineffective, and in practice NSAIDs are often used by patients with neuropathic pain.28 It is possible

that NSAIDs have an effect in patients with mild pain or pain with an inflammatory component or they may have a placebo

effect in some patients.28

Other antidepressants have a limited role in the treatment of neuropathic pain. TCAs are preferred

over selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for patients

with neuropathic pain.

Venlafaxine is the only SNRI available in New Zealand which has evidence of efficacy in the treatment of neuropathic

pain.29 Consultation with a neurologist or clinician in a pain clinic is recommended before using venlafaxine

as a treatment for patients who have not responded sufficiently to initial treatment. Duloxetine is recommended as a potential

first-line treatment for neuropathic pain by international guidelines,1 however, this medicine is not available

in New Zealand.

There is currently no evidence that SSRIs are effective in the treatment of neuropathic pain. 21

Opioids are reserved for patients with severe neuropathic pain due to the potential adverse effects,

including dependency.2, 21 Discussion with a clinician experienced in treating pain is recommended before prescribing

opioid-based medicines for patients with neuropathic pain that is not controlled by other approaches.

Topical treatment of cutaneous neuropathic pain

Topical capsaicin cream (0.075%) is a treatment option for patients with localised, cutaneous neuropathic pain.21 It

is fully subsidised by prescription endorsement for patients diagnosed with post-herpetic neuralgia or diabetic peripheral

neuropathy. Capsaicin cream produces a burning sensation on application; patients should wash hands immediately after

application and avoid transferring the product to eyes or mucous membranes.29

Lidocaine 2.5% + prilocaine 2.5% patches (unsubsidised) may be a second-line topical analgesic for patients who do not

tolerate capsaicin cream.21

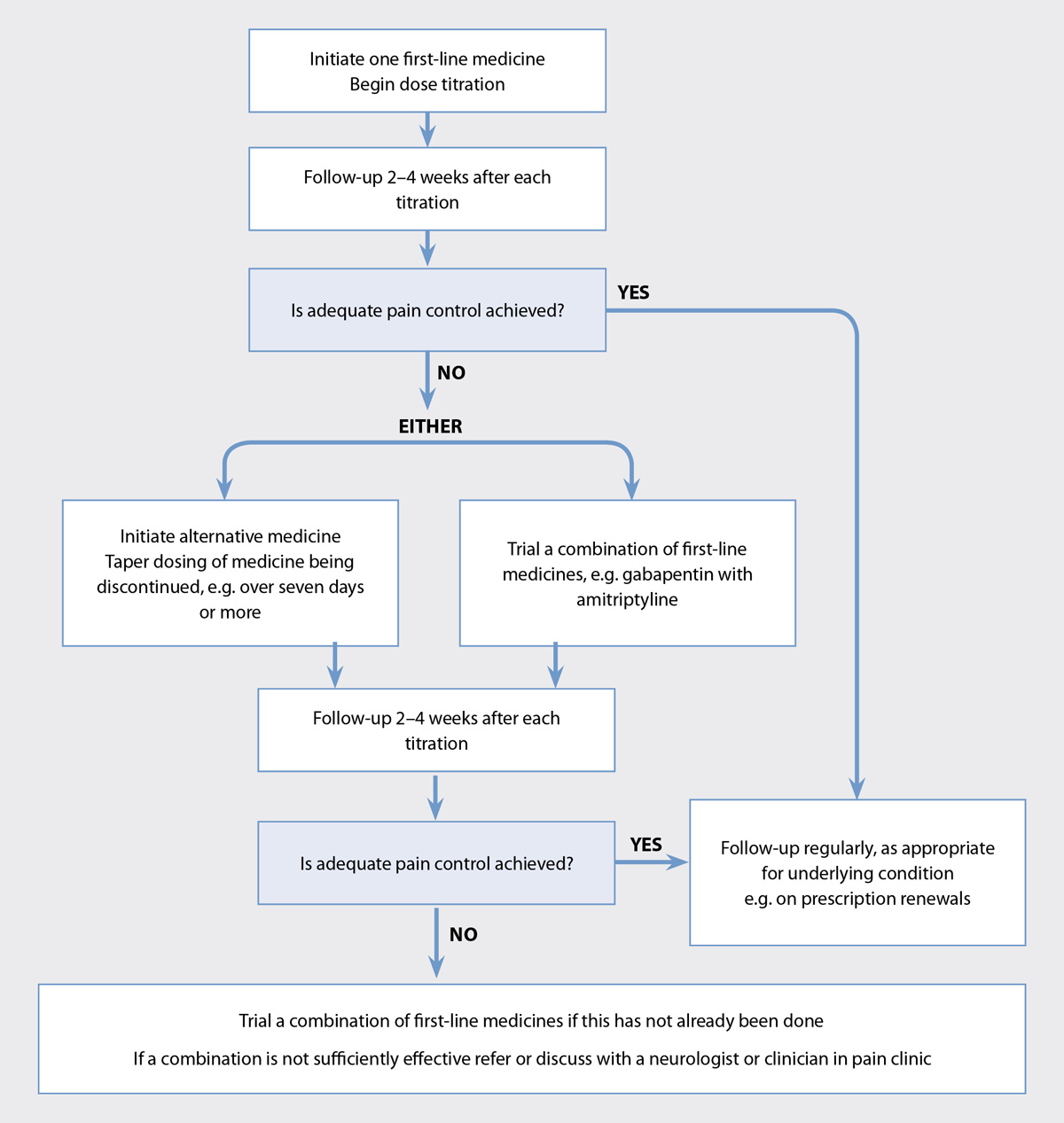

Initiating and optimising treatment

For most analgesics, dosing should start low and be titrated upwards. Practice points for optimising treatment for neuropathic

pain are shown in Figure 1. Treatment success is measured by subjective assessment of the patient’s level of pain, sleep

disruption and ability to function in daily life.

Figure 1. Optimising analgesia for neuropathic pain, except trigeminal neuralgia.1, 5

If sufficient control is not obtained with the first medicine trialled, switch to another of the recommended

initial medicines, e.g. from a TCA to gabapentin, or use a combination of medicines. If medicines are switched, gradually

reduce the dose of the medicine being withdrawn, e.g. over seven days or more, while the new medicine is initiated in

order to provide continuous treatment. If medicines are combined, aim for a combination of medicines that have different

analgesic mechanisms.30 Combination treatment with a TCA and gabapentin provides better outcomes, at lower

doses, without additional adverse effects, than either of these medicines alone in higher doses. For example, nortriptyline

50 mg, daily, with gabapentin 2000 mg, daily in divided doses, provided better pain relief in one study than nortriptyline

60 mg, daily or gabapentin 2250 mg, daily.30

Treating trigeminal neuralgia

Carbamazepine should be the initial treatment trialled for patients with trigeminal neuralgia.1 If carbamazepine

is ineffective, consider consulting with a neurologist or pain clinic as there is little evidence from clinical trials

to guide prescribing of other medicines.1, 31 Lamotrigine or baclofen (unapproved indications) have been suggested

as potential second-line treatment options for patients with trigeminal neuralgia.31

Best practice tip: Consider strategies for reducing “piles of

pills” for patients with long-term pain, e.g. more frequent dispensings during an analgesic trial. Patients with chronic

pain may have comorbidities and be taking a number of medicines; consider whether they are eligible for the Long Term

Condition service to simplify their medicine regimen.

Best practice tip: Consider strategies for reducing “piles of

pills” for patients with long-term pain, e.g. more frequent dispensings during an analgesic trial. Patients with chronic

pain may have comorbidities and be taking a number of medicines; consider whether they are eligible for the Long Term

Condition service to simplify their medicine regimen.

For further information, see: “Piles of pills: Prescribing appropriate

quantities of medicines”, BPJ 69 (Aug, 2015).

For further information, see: “Piles of pills: Prescribing appropriate

quantities of medicines”, BPJ 69 (Aug, 2015).