Pain assessment

All patients in the last days of life should have regular pain evaluations.7, 8 However, the assessment of pain in this setting can be challenging as patients become less responsive or begin to experience delirium.*1, 3 It can also be difficult to assess pain in patients with limited communication due to cognitive impairment.1, 3

Pain evaluation usually involves determining:4, 9

- The severity of the pain. A tool to measure pain intensity is recommended, e.g. verbal descriptor, numerical scale, Faces Pain Scale. The Abbey Pain Scale can be used to assess pain in patients with limited or no communication.

- The type(s) of pain present (see box about adjuvant or co-analgesics):

- Somatic, e.g. aching, throbbing, gnawing, localised

- Visceral, e.g. deep, dull, aching, cramping

- Neuropathic, e.g. burning, shooting, tingling

- Bone, e.g. constant, deep

- Whether there is a specific cause that can be treated, e.g. urinary retention, constipation

- Any factors that relieve and exacerbate pain, e.g. body position, movement, temperature, psychological factors, spiritual concerns about the dying process

- The impact of pain on all aspects of the patient’s wellbeing and functioning

Practice Point: Consider other practical ways to identify that patients with limited communication may be experiencing pain, e.g. by recognising facial expressions or non-specific distress behaviours such as restlessness, moaning, muscle tension.1, 3, 8 If it is still uncertain whether a patient with limited communication is in pain after an initial assessment, an empiric trial of analgesics may be appropriate.

Practice Point: Consider other practical ways to identify that patients with limited communication may be experiencing pain, e.g. by recognising facial expressions or non-specific distress behaviours such as restlessness, moaning, muscle tension.1, 3, 8 If it is still uncertain whether a patient with limited communication is in pain after an initial assessment, an empiric trial of analgesics may be appropriate.

*For further information, see: “Managing delirium and psychological symptoms in the last days of life”

Making the patient comfortable and pain free is the primary goal in the last days of life. Most commonly this is achieved with the use of analgesic medicines (see: “Morphine is usually the first-line pharmacological treatment”), but non-pharmacological strategies (see below) should be used as well if appropriate.4, 6, 9

Ideally, pain management will have been discussed with the patient and their family/whānau prior to the last days of life so that a plan is already in place, i.e. advance care planning, see: www.hqsc.govt.nz/our-work/advance-care-planning/.

Non-pharmacological pain management strategies:3, 4, 6, 9

- Acknowledge and validate the patient’s pain experience, reassure them that every effort will be made to manage their pain

- Minimise exposure to triggers that exacerbate pain, e.g. particular movements or body positions, psychological distress

- Encourage the family/whānau to spend time with the patient which may help to ease their pain

- Regularly reposition the patient (if possible and appropriate). This can be comforting, pressure relieving, and help to reduce stiffness and muscle aches. Provide pressure relieving aids as required.

- Suggest relaxation or distraction techniques depending on the patient’s level of functioning, e.g. listening to music or a podcast, watching television, guided imagery (a technique where the person imagines positive images or scenarios, e.g. favourite holiday destination), reminiscing, mindfulness, meditation or prayer (depending on the patient’s spiritual or cultural beliefs)

- Use a hot or cold pack

- Gentle massage or touch (i.e. by family/whānau)

- Create an ambient environment, e.g. by lowering lights, setting an appropriate room temperature, aromatherapy

Support the use of other techniques and methods for pain relief that the patient or their family/whānau want to try if they are unlikely to cause harm, e.g. traditional techniques (such as Rongoā Māori, Ayurvedic or Chinese herbal medicines), homeopathy, acupressure/acupuncture.

Morphine is usually the first-line pharmacological treatment

Opioids administered subcutaneously are recommended for patients with pain in the last days of life.4, 6 Patients already taking opioids orally usually require conversion to a subcutaneous form, i.e. convert oral doses of morphine to subcutaneous doses of morphine (see: “Oral doses should be converted to subcutaneous”).

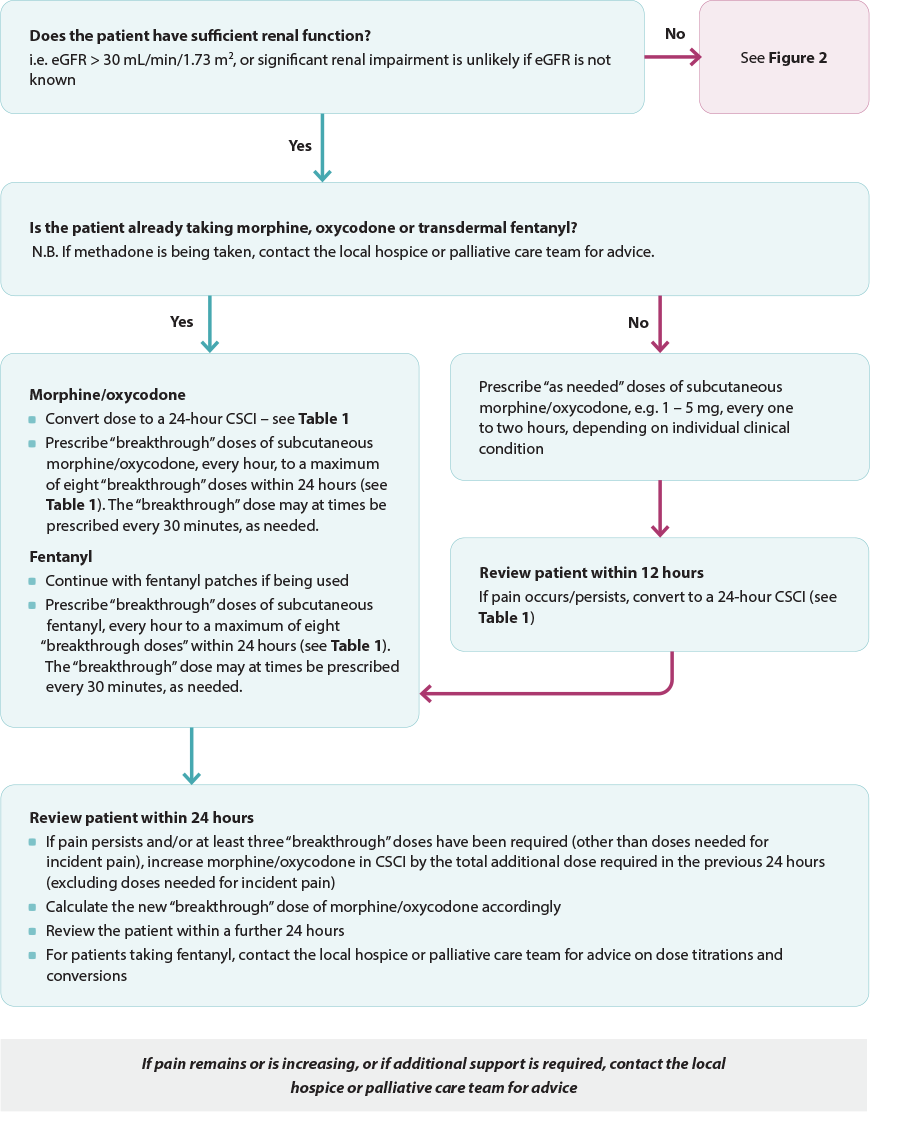

Morphine is the first-line pharmacological treatment for most patients in the last days of life (Figure 1).4, 6 Oxycodone may be considered for patients who are unable to tolerate morphine.4 If a patient has significant renal impairment (i.e. eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2), the active metabolites of morphine or oxycodone can accumulate resulting in opioid toxicity.4 Symptoms and signs of opioid toxicity include myoclonic jerks, excessive sedation or confusion, restlessness and hallucinations.1, 4

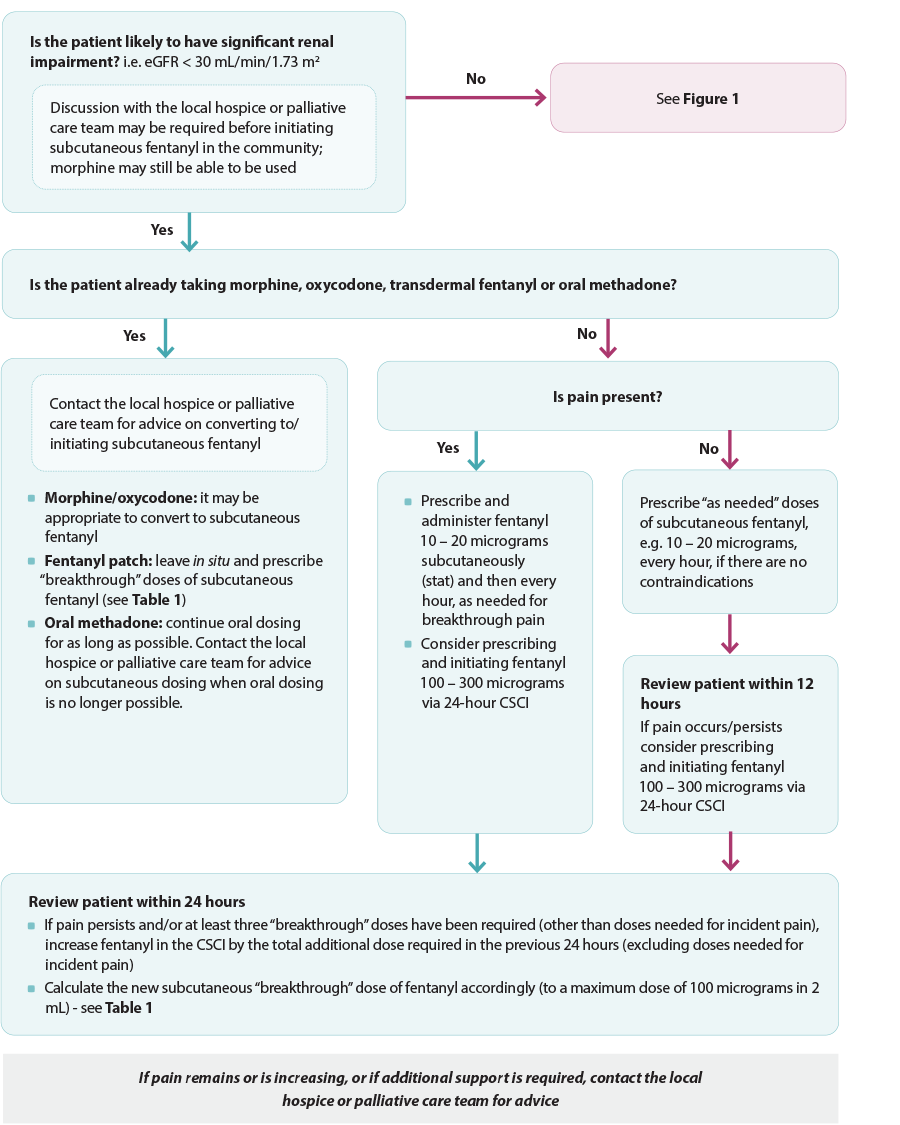

Fentanyl (subcutaneous) may be appropriate in patients with significant renal impairment (Figure 2);4 however, dosing and administration is more complicated than morphine. Therefore, in practice, morphine may still be used in some patients with renal impairment in the last days of life, particularly if doses are not too high. In the last days of life, contraindications for treatment also become less absolute.

Practice Point: Anticipatory prescribing of “as needed” doses of analgesia is also recommended in patients without current pain (Figure 1); if pain arises the “as needed” dose can be administered and then regular dosing initiated.6

Practice Point: Anticipatory prescribing of “as needed” doses of analgesia is also recommended in patients without current pain (Figure 1); if pain arises the “as needed” dose can be administered and then regular dosing initiated.6

Figure 1. Anticipatory prescribing for pain algorithm for patients with normal renal function in the last days of life. Adapted from South Island Palliative Care Workstream, 2020.6

CSCI = continuous subcutaneous infusion

Figure 2. Anticipatory prescribing for pain algorithm for patients with impaired renal function in the last days of life. Adapted from South Island Palliative Care Workstream, 2020.6

CSCI = continuous subcutaneous infusion

Oral doses should be converted to subcutaneous

Many patients entering into their last days of life will already be established on an analgesic treatment regimen, usually with a long-acting opioid (either oral or transdermal). For patients currently taking an opioid orally, conversion to a subcutaneous dose for 24-hour continuous subcutaneous infusion is recommended in the last days of life (Table 1).4, 6 This is often required as the patient’s level of consciousness and alertness is expected to reduce during this period, which makes swallowing no longer possible.6, 8 If a patient is currently using transdermal fentanyl, patches can remain in situ and subcutaneous fentanyl (unapproved route) can be prescribed and administered on an “as needed” basis for breakthrough pain (Table 1).4, 6

Practice Point: Fentanyl patches take 72 hours to reach steady state and should not be initiated in patients who are opioid naïve.10 The lowest dose fentanyl patch (12.5 micrograms per hour) is equivalent to up to 60 mg of oral morphine.10

Practice Point: Fentanyl patches take 72 hours to reach steady state and should not be initiated in patients who are opioid naïve.10 The lowest dose fentanyl patch (12.5 micrograms per hour) is equivalent to up to 60 mg of oral morphine.10

Table 1. Dose conversion and “breakthrough” dose calculations for subcutaneous morphine, oxycodone and fentanyl.6

| Dose conversion calculations |

| Conversion from |

Conversion to |

Calculation |

| Oral morphine |

Subcutaneous morphine |

Divide oral dose by 2 |

| Oral oxycodone |

Subcutaneous oxycodone |

Divide oral dose by 1.5 or multiply by 0.667 (to get two-thirds of oral dose) |

| Subcutaneous dose |

24-hour dose for continuous subcutaneous infusion |

Total number of doses (regular + “breakthrough”) required in previous 24 hours (excluding doses needed for incident pain) |

|

Opioid conversion guides are available from the New Zealand Formulary: nzf.org.nz/nzf_70672#nzf_70708 Opioid conversion guides are available from the New Zealand Formulary: nzf.org.nz/nzf_70672#nzf_70708

An online Australian-based opioid conversion calculator is available from: www.eviq.org.au/clinical-resources/eviq-calculators/3201-opioid-conversion-calculator An online Australian-based opioid conversion calculator is available from: www.eviq.org.au/clinical-resources/eviq-calculators/3201-opioid-conversion-calculator

|

| Subcutaneous “breakthrough” dose calculations |

| Subcutaneous “breakthrough” dose of morphine/oxycodone is equivalent to one sixth of the total 24-hour dose, to be prescribed every hour (occasionally every thirty minutes), as needed |

| Subcutaneous “breakthrough” dose of fentanyl is equivalent to the hourly dose of transdermal fentanyl to a maximum dose of 100 micrograms in 2 mL |

Prescribe “as needed” doses for breakthrough pain

Subcutaneous morphine/oxycodone doses should also be prescribed and administered on an “as needed” basis for breakthrough pain (Table 1).6 “Breakthrough” doses are generally one-sixth of the total 24-hour dose and should be prescribed every hour (occasionally every thirty minutes) as needed. A maximum of eight “breakthrough” doses administered within 24 hours are recommended.6 If the patient has incident pain, e.g. pain associated with movement such as changing position, dressing changes, administer the “as needed” dose prior to the activity.6

If pain persists and/or at least three “breakthrough” doses have been required (other than those needed for incident pain) within 24 hours, increase the dose of the opioid in the continuous subcutaneous infusion by the total additional dose required in the previous 24 hours (excluding doses needed for incident pain).6 A new “breakthrough” dose will now need to be calculated.6 If pain still persists after a further 24 hours, contact the local hospice or palliative care team.6

Adjuvant or co-analgesics should be continued for specific indications until swallowing is no longer possible as withdrawal may worsen symptoms, e.g. tricyclic antidepressants or anti-epileptics for neuropathic pain, systemic corticosteroids for pain related to raised intracranial pressure, bisphosphonates or NSAIDs for bone pain.3, 8 If the medicine is not being used for analgesia alone it may be able to be converted to a subcutaneous route if it is still required, e.g. dexamethasone. Contact the local hospice or palliative care team for advice if required.

Adjuvant or co-analgesics should be continued for specific indications until swallowing is no longer possible as withdrawal may worsen symptoms, e.g. tricyclic antidepressants or anti-epileptics for neuropathic pain, systemic corticosteroids for pain related to raised intracranial pressure, bisphosphonates or NSAIDs for bone pain.3, 8 If the medicine is not being used for analgesia alone it may be able to be converted to a subcutaneous route if it is still required, e.g. dexamethasone. Contact the local hospice or palliative care team for advice if required.

Laxatives are usually only required if constipation is causing discomfort in the last days of life

Almost all patients taking strong opioids experience persistent constipation and are routinely co-prescribed an oral laxative regimen. In the last days of life, however, constipation may not cause symptoms and the benefit from laxatives during this time may be limited.1, 8 Oral laxatives are ceased once swallowing is no longer possible. Suppositories or enemas are rarely required in the last days of life and they should only be considered if constipation is causing significant discomfort to the patient.8

Acknowledgement

Thank you to the following experts for review of this article:

- Dr Kate Grundy, Palliative Medicine Physician, Clinical

Director of Palliative Care, Christchurch Hospital Palliative

Care Service and Clinical Lecturer, Christchurch School of

Medicine

- Vicki Telford, Clinical Nurse Specialist, Nurse Maude

Hospice Palliative Care Service, Christchurch

- Dr Helen Atkinson, General Practitioner and Medical

Officer, Harbour Hospice

- Dr Robert Odlin, General Practitioner, Orewa Medical

Centre

- Fraser Watson, Extended Care Paramedic Clinical Lead,

Hato Hone St John

N.B. Expert reviewers do not write the articles and are not responsible for the final content.

bpacnz retains editorial oversight of all content.

This resource is the subject of copyright which is owned by bpacnz.

You may access it, but you may not reproduce it or any part of it except in the limited situations described in the

terms of use on our website.

Article supported by Te Aho o Te Kahu, Cancer Control Agency.

References

- PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board. Last days of life (PDQ®): health professional version. In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US) 2007 (updated 2023). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65868/ (Accessed September, 2023).

- Crawford GB, Dzierżanowski T, Hauser K, et al. Care of the adult cancer patient at the end of life: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. ESMO Open 2021;6:100225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100225

- Azhar A, Hui D. Management of physical symptoms in patients with advanced cancer during the last weeks and days of life. Cancer Res Treat 2022;54:661–70. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2022.143

- Ministry of Health - Manatū Hauora. Te Ara Whakapiri Toolkit: care in the last days of life. 2017. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/te-ara-whakapiri-toolkit-apr17.pdf (Accessed September, 2023).

- NHS Scotland. Scottish palliative care guidelines. Available from: https://www.palliativecareguidelines.scot.nhs.uk/guidelines.aspx (Accessed September, 2023).

- South Island Palliative Care Workstream. Te Ara Whakapiri Symptom management in the last days of life. 2020. Available from: https://www.sialliance.health.nz/wp-content/uploads/Symptom-management-in-the-last-days-of-life_SIAPO.pdf (Accessed September, 2023).

- Chapman L, Ellershaw J. Care in the last hours and days of life. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;48:52–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpmed.2019.10.006

- Crawford GB, Hauser KA, Jansen WI. Palliative care: end-of-life symptoms. In: Olver I, ed. The MASCC Textbook of Cancer Supportive Care and Survivorship. Cham: Springer International Publishing 2018. 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90990-5_5

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Care of dying adults in the last days of life. 2015. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng31 (Accessed September, 2023).

- MacLeod R, Macfarlane S. The palliative care handbook 9th edition. 2019. Available from: https://www.hospice.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Palliative-Care-Handbook.pdf (Accessed September, 2023).