Death is the inevitable closing chapter in a person’s life. There are countless narratives that can lead people to this destination: for some, the possibility of death has been long anticipated due to chronic illness, whereas others may face it unexpectedly.

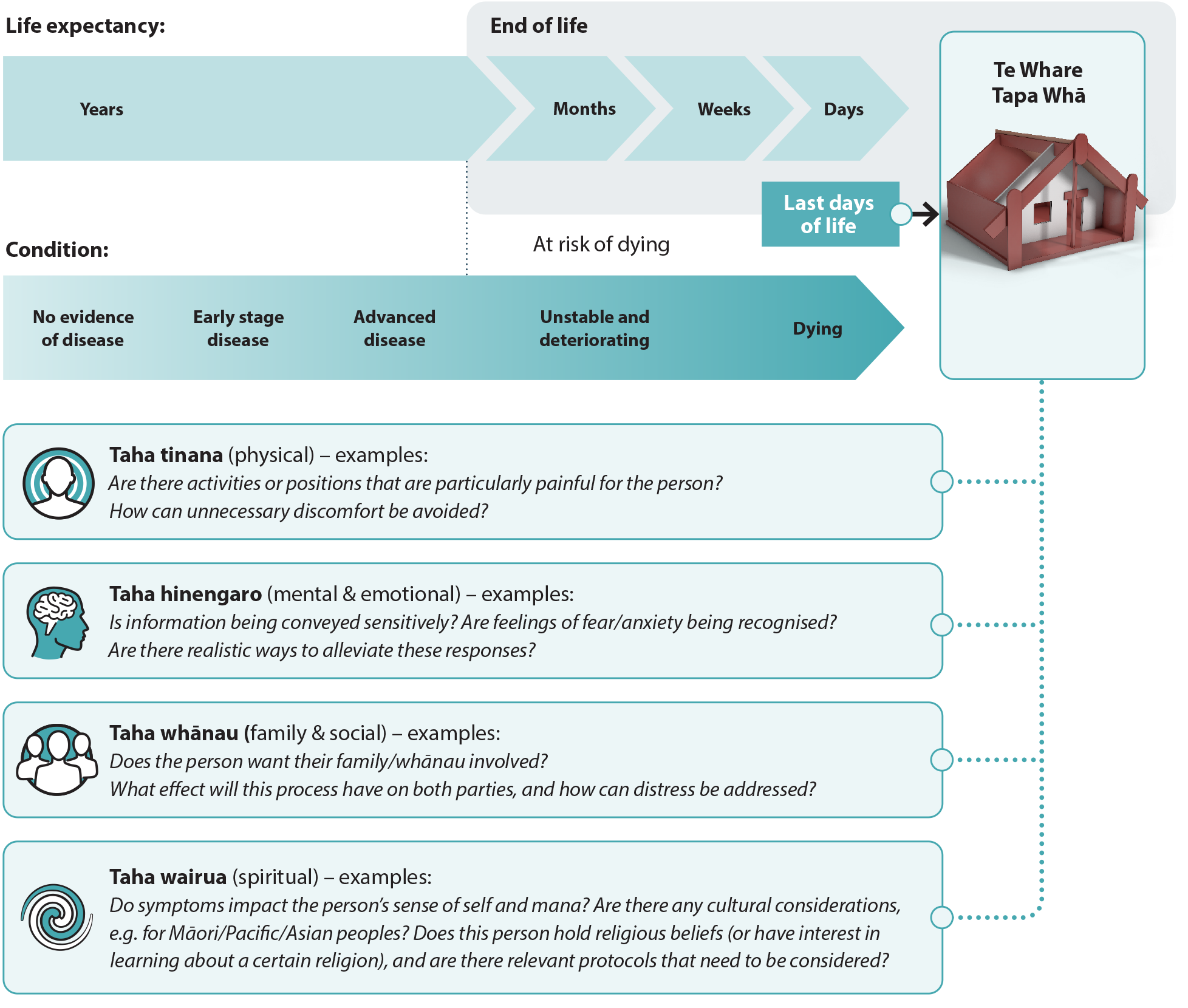

The term “last days of life” specifically relates to the period of time in which death is considered imminent (Figure 1).1 Given the unpredictable nature of human perseverance and diverse pathways leading to death, the duration of this period can vary, and may be measured in hours or days.1 For many, the concept of having a “good death” is highly dependent on how the last days of life unfold, and the manner in which a person dies often persists in the memories of those left behind.2

End of life care should ideally be delivered as part of a multidisciplinary clinical service.3 In New Zealand, an estimated 31% of people die in residential aged care facilities and 22% die in private residences.4 In these situations, general practices may be tasked with helping people and their family/whānau navigate the last days of life; either as the primary provider of end of life care services or in collaboration with a multidisciplinary team.4 The general practice team will often work closely with district nurses, aged residential care facility staff, hospice services and in some cases, ambulance services, when providing end of life care.

General practitioners, nurse practitioners and practice nurses are already integrated into the pathways that lead to end of life care; they are often familiar with the patient’s history, provide clinical care and support throughout their lifetime and are well positioned to identify those with a life-limiting illness (particularly as people begin seeking more regular care). As New Zealand’s population ages, the role of the general practice team within this process will inevitably increase. Terminally ill people should be provided with a consistent standard of care, however, there are considerable challenges that primary care health professionals face when trying to provide end of life care in the community, including:5

- Funding and resource limitations

- Capacity and time constraints

- Access to training and guidance

New Zealand-specific guidance is now available

In 2017, “Te Ara Whakapiri: Principles and guidance for the last days of life” was published by the Ministry of Health (Manatū Hauora) providing a uniquely New Zealand perspective to guide best practice care of people in their final days of life.1 Specific aspects of this work were updated in 2020.6

Te Ara Whakapiri details essential components and considerations, flowcharts and checklists, for providing quality and consistent care for adults in their last days of life, regardless of the setting, e.g. home, a residential care facility, hospice or hospital.1 It also outlines various overarching principles relating to the delivery of end of life care and the health system(s) facilitating this.1 While certain concepts are dependent on health policy and system-level action, those most relevant to primary care professionals include that:

- Care should meet the individualised needs of the person and their whānau.1 People in their last days of life may experience physical discomfort, in addition to psychosocial and spiritual distress; factors that are often interconnected.7 However, no two journeys leading to the last days of life are the same. Each person’s unique background gives rise to diverse perspectives, challenges and coping abilities. The universal principles of Te Whare Tapa Whā (Figure 1) can be used as a framework to guide and deliver individualised care across all dimensions of a person’s wellbeing.1, 8

- All information relating to the status of people in their last days of life, their care plan and treatment should be communicated clearly and respectfully.1 Shared decision-making should always be considered; care providers must actively seek input from the person and their family/whānau and create opportunities for them to provide feedback.1 For further information, see: “Tips for communication with family/whānau”.

- Details of conversations and decisions should be documented and considered in the context of any existing advance care plan or advance directive(s).1 See: “A reminder to think ahead: advance care planning”.

- Family/whānau should also be supported. It is important to pre-emptively discuss with the family/whānau their role, including how they can be involved in care, potentially difficult decisions (e.g. relating to feeding and hydration, discontinuing non-essential medicines) and physiological changes to look for that may indicate impending death (so they can be prepared).1 Following death, bereavement risk should also be considered, and support arranged if necessary (see: “Assessing family/whānau bereavement risk”).1

Figure 1. The end of life and last days of life.

Adapted from Te Ara Whakapiri, Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora.1

A reminder to think ahead: advance care planning

A patient’s transition into the last days of life can be simplified through proactive discussions that prioritise their autonomy and decision-making while they are still competent and have time to carefully consider their options. This process is known as advance care planning and should be strongly encouraged in all patients with a terminal illness, and followed up to ensure it has been completed.

Advance care planning helps to establish the person’s preferences and goals for care according to their beliefs, values and lived experience.9 This approach aims to reduce the burden of decision-making, uncertainty and the likelihood of unwanted interventions at the end of life.9 Discussions around these topics can be challenging, evolve over multiple consultations and can include the family/whānau if the person wishes.9 This process may also result in the documentation of specific advance directives, particularly if the person has strong views regarding specific medical interventions, or the establishment of an enduring power of attorney (if not already appointed).9 Advance care plans and advance directives should be signed by the patient and the lead health practitioner, dated and a copy readily available to be shared with any health provider involved in the patient’s care;9 this is especially useful if ambulance services are required or other health providers not familiar with the patient become involved in delivering acute care.

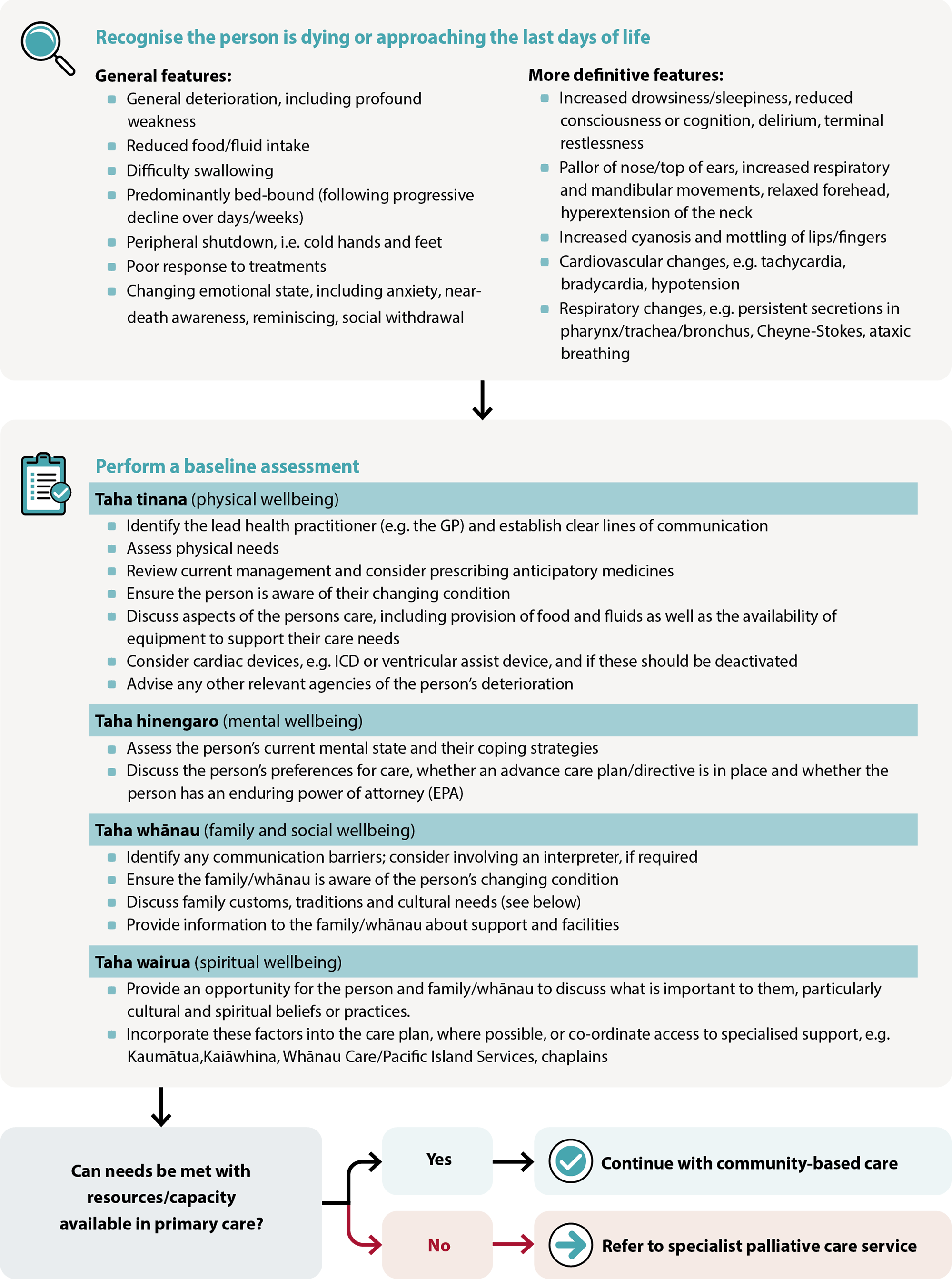

The baseline assessment provides an opportunity to comprehensively evaluate the needs of the patient (Figure 2); if these needs exceed the resources or capacity of the primary care provider, the patient should be referred to a specialist palliative care service.1

For a comprehensive checklist covering essential aspects of a baseline assessment for people in their last days of life, click here.

For a comprehensive checklist covering essential aspects of a baseline assessment for people in their last days of life, click here.

Figure 2. General overview of a baseline assessment for people in the last days of life.1, 10, 11

Recognising that a person is dying

Clinical judgement and experience is used to determine when a person is approaching the last days of life.1 However, recognising this transition can be a significant challenge regardless of the care setting as:1, 10, 11

- Symptoms and signs can be subtle and may vary depending on the patient’s underlying condition(s), e.g. profound weakness, changes in respiratory patterns and mental state, reduced food/fluid intake (see Figure 2 for a comprehensive list)

- Clinical deterioration may also indicate a life-threatening but potentially recoverable condition, e.g. opioid toxicity, infection or hypercalcaemia. The decision to investigate or treat depends on individual clinical circumstances, patient/family/whānau wishes or advance directive(s).

To access the “Recognising the dying person flow chart”, click here.

To access the “Recognising the dying person flow chart”, click here.

As such, there is likely to be an element of uncertainty during this process. In general, the possibility of incorrectly identifying this transition is outweighed by the importance of facilitating timely/open discussions and redirecting care towards individualised comfort and support.1 This also provides the person and their family/whānau with an opportunity to understand and process the possibility of imminent death.1 End of life conversations can be difficult depending on the person’s history, cultural values, beliefs and attitudes, but are best facilitated using open and honest communication (see: “Tips for communication with family/whānau”).1, 2

If a person’s level of consciousness, functioning/mobility, oral intake or ability to perform self-care later improves after initially deciding they were in the last days of life, a reassessment of the current care plan should be performed to ensure it remains suitable.10 The person and their family/whānau should also be given an opportunity to express any concerns.

Determine roles and establish clear lines of communication

After determining that a person is likely to be in their last hours or days of life, a lead health practitioner should be identified/documented (if not already designated) and a clear process established regarding when and how to contact them.1 Ensure contingencies are in place for support both within and outside working hours; a designated alternative contact should be identified, which may include services outside of general practice, e.g. secondary care, palliative care, district nurses, pharmacy, and in some cases paramedicine/ambulance services.

The lead health practitioner should in turn identify and document who the key spokesperson and/or first contact is from within the family/whānau, as well as whether there is an enduring power of attorney (and if this has been, or should be, activated).1 Regular communication with nominated people is essential, particularly if care plan implementation takes place at home.

Establishing a strong working relationship with local palliative care or hospice teams should be a priority in primary care, particularly for general practices with high numbers of older patients. This collaborative approach is particularly important when dealing with patients who have complex needs, as it enables timely discussion and advice to provide the best support possible.

Assess the person’s physical needs

There are five main symptoms that need to be proactively considered for every dying person: pain, nausea/vomiting, dyspnoea (breathlessness), respiratory tract secretions and delirium. A physical needs assessment can help identify the priorities of care, providing practical information on which symptoms are most likely to cause the person discomfort and distress, and what additional assistance may be required.1

This evaluation may consider:1, 10

- Level of consciousness

- Pain severity and type. Consider physical signs of pain, e.g. facial grimacing, restlessness, tachycardia.

- Functional status, e.g. swallowing difficulties, balance problems and falls risk

- Skin integrity, e.g. pressure injuries, skin tears, skin dryness, ulceration, infections

- Gastrointestinal/genitourinary complaints. Nausea, vomiting and anorexia are common. Abdominal fullness may indicate constipation or urinary retention. Consider catheterisation if not already in place.

- Respiratory symptoms, e.g. dyspnoea, respiratory tract secretions, cough

- Neurological and psychiatric features, e.g. delirium (which may include agitation and terminal restlessness), confusion, insomnia, fear, anxiety/depression

Not all people in their last days of life are able to communicate information about their physical needs or goals; include family/whānau in discussions, if possible (particularly if they are the ones who will be primarily delivering care).1

Discuss symptom management and prescribe anticipatory medicines

People in their last days of life can present with a wide range of symptoms that may change over time; this should be anticipated where possible and a management plan put in place.1

Non-pharmacological management strategies should be used as much as possible, particularly if adverse effects of medicines are a concern or if people are wanting to “die a more natural death”.13, 14 Examples include setting up a comfortable environment/atmosphere, playing music, using relaxation techniques (e.g. deep breathing), and regularly repositioning the person if possible. However, pharmacological management is invariably required. Anticipatory medicine prescribing is usually implemented for people choosing to die at home to ensure carers can provide timely symptom relief without the need for in-person clinician assessment. Medicine regimens can sometimes be complicated as symptoms may occur concurrently, and the recommended medicines may have overlapping indications (e.g. opioids are used for both pain and dyspnoea),6 or interact (e.g. opioids and benzodiazepines may enhance analgesia but can also increase sedation).15

Some medicines or regimens used for symptom management in the last days of life are "unapproved"

During care in the last days of life, the use of some medicines for symptom management involves unapproved (“off-licence”) indications, doses or routes of administration (see linked articles above for specific information). Under Section 25 of the Medicines Act 1981, authorised prescribers working within the scope of their practice can procure the supply of any medicine for use in patients under their care. This can include unapproved medicines and permits the supply of approved medicines for unapproved uses.

In these situations, the lead health practitioner should first identify whether there is a recognised guideline that endorses routine use:6, 10

- If use is justified under a recognised guideline, follow the usual process of obtaining verbal consent, including requirements under The Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights 1996, e.g. explain what is being prescribed and why, any safety concerns, and document this in clinical records

- Written consent may be required if there is minimal evidence to support use, where the evidence for efficacy/safety of medicine use in such a manner is uncertain, or if there is significant risk of adverse effects

- If routine use is not supported by a recognised guideline, it may still be justified when used in people in the last days of life if there is still some evidence to support a potential benefit (e.g. case studies, peer reviewed textbooks) and it is considered that these potential benefits outweigh possible risks when standard treatment approaches have not provided benefit or are inappropriate. If such criteria are met, documented verbal consent is required at a minimum (although written consent is preferable given the low strength of evidence).

- If the patient is unable to give consent in any form, family/whānau are not able to give or withhold consent on their behalf unless they are a welfare guardian or designated as a legal Enduring Power of Attorney (EPA). If no such legal proxy exists in this situation, the authorised prescriber can still proceed in the best interests of the patient after a discussion with family/whānau.

- If an unapproved medicine is used, ensure relevant requirements under Section 29 of the Medicine Act 1981 are met

Practice point: Prescribing three to five days’ of “as needed” medicines for a patient in the last days of life is a reasonable balance between convenience and wastage if the dose or medicine is changed or no longer required. A plan should be established for replenishing anticipatory medicine supplies should the patient continue living beyond this timeframe so there is no interruption in the delivery of symptom relief. Anticipatory medicine prescribing may also assist ambulance personnel or other acute healthcare providers, should they become involved, as they may not always carry the medicines recommended in these resources (see articles below for specific recommendations).

Practice point: Prescribing three to five days’ of “as needed” medicines for a patient in the last days of life is a reasonable balance between convenience and wastage if the dose or medicine is changed or no longer required. A plan should be established for replenishing anticipatory medicine supplies should the patient continue living beyond this timeframe so there is no interruption in the delivery of symptom relief. Anticipatory medicine prescribing may also assist ambulance personnel or other acute healthcare providers, should they become involved, as they may not always carry the medicines recommended in these resources (see articles below for specific recommendations).

Click on the following links to access further information about managing each of the five main symptoms that can occur in the last days of life. These additional articles include anticipatory prescribing recommendations and flow charts adapted from the Te Ara Whakapiri updates,6 accompanied by information contextualised for patients choosing to die in the community with the support of their general practice team.

N.B. This guidance is intended for patients experiencing an “uncomplicated death”. Further secondary care or specialist palliative care input may be required for patients already taking significant opioid doses, with complex medicine regimens, or if symptoms have already been challenging to manage.

Syringe drivers

Subcutaneous medicine administration is often used in the last days of life, including when a person:16, 17

- Has difficulty swallowing oral medicines

- Requires a medicine with no oral formulation

- Is too weak or fatigued to reliably take medicines at the prescribed times

- Requires timely onset of action and needs a constant level of medicine for symptom control, i.e. steady plasma concentrations

Syringe drivers are battery-operated pumps that administer a continuous subcutaneous infusion of essential medicine(s).17 The two syringe drivers currently in use in New Zealand are Niki T34 or the newer model BD Bodyguard T.18, 19

Hospice or district nursing services can provide equipment and personnel who can work with general practice teams, patients and their family/whānau to help set up the syringe driver. Depending on the care plan, the family/whānau may sometimes be tasked with changing pre-filled syringes collected from the pharmacy once the driver is set up and instructions are given (if willing and competent).18 In some regions family/whānau may also be provided with education and support to administer as needed subcutaneous medicines for breakthrough symptoms.

Other considerations for care plans in the community1

Discontinue non-essential medicines. Care in the last days of life should primarily focus on relieving symptoms and promoting quality of life. Therefore, continued use of medicines for managing long-term conditions is often no longer necessary (e.g. statins, antihypertensives, urate-lowering treatment[s]); many of these medicines are taken orally (which may no longer be possible), and continuation may increase “pill burden” or cause interactions with medicines introduced for symptom control.17 Possible exceptions include anticonvulsants or other medicines used to control symptoms, e.g. a diuretic for heart failure, that could impact comfort or cause distress if withdrawn.7, 20 In some cases, essential long-term medicines may be switched from an oral to subcutaneous route if possible, e.g. levetiracetam, dexamethasone. Most diabetes medicines can be stopped in the last days of life, however, insulin should usually be continued in patients with type 1 diabetes.21 Discontinuing insulin may be appropriate for patients with type 2 diabetes if they have previously only required small doses to achieve glycaemic control.21

- Food and fluids. People should be encouraged to continue eating and drinking as long as they feel comfortable doing so (including via parenteral feeding, if appropriate). In most cases, people will become gradually less interested or capable of eating/drinking as they approach death, and increasing food/fluid intake is unlikely to prolong life or decrease their discomfort.22 Trying to compel intake may also cause further distress or result in aspiration, particularly if they have swallowing difficulties.22 However, some people may find pleasure and comfort from tasting food and derive social/cultural benefits from sharing meals with their family/whānau.22

- Supportive equipment. Identify whether the person requires access to supportive equipment, e.g. syringe drivers, pressure relieving mattresses/cushions, hoist or electric bed, incontinence products or commodes. Contact your local PHO, allied health or hospice service for more information on funding options or equipment loans. An occupational therapist can assess patient-specific needs if required. In some cases, families choose to purchase equipment themselves.

- Oxygen. The use of domiciliary oxygen is not common in the last days of life unless a patient has established hypoxia due to disease, however, a new prescription may occasionally be considered in the dying phase for certain patients (but this may be dependent on local policies and advice). Dyspnoea is primarily managed using pharmacological treatment in the last days of life, supported by non-pharmacological strategies, as appropriate.

- Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs). In most cases, an ICD should be deactivated as the person approaches death.23 If not turned off, the device may cause repeated shocking in response to natural arrhythmic patterns that occur close to death;23, 24 this is likely to be distressing for both the person and their family/whānau. Deactivating an ICD will not cause a worsening of cardiac output.

- Cultural, religious and spiritual needs. Identify any specific traditions, customs or practices that are important to the person and consider how these can be incorporated into the care plan. For some, the last days of life are a time when they want to re-explore concepts of faith and cultural links that have not previously been central to their life.

- Share information with relevant agencies regarding the person’s deterioration. Depending on the patient’s clinical history, other health services may already be involved in their care, e.g. oncology, geriatrics, district nursing services, residential care facilities. While it may not be practical or applicable in every situation, these groups should be identified and contacted to inform them of the persons deteriorating condition (particularly if upcoming appointments are scheduled). N.B. Ensure requirements under the Privacy Act 2020 are adhered to.

Providing a management summary sheet is good practice for supporting acute health providers outside of the usual care team. For example, emergency ambulance services deal with many cases relating to end of life assessment and care support in the community, particularly if unexpected deterioration occurs outside of usual work hours. Extended Care Paramedics are increasingly involved in providing care for these patients in some areas of the country. Completing a brief management summary sheet can be an invaluable resource as this provides clinical context and guidance to assist these acute health providers in making timely decisions about the patient’s care (that align with their care plan). In New Zealand, paramedics have a legal obligation to provide care to vulnerable and critically unwell people; deviations from life-preserving obligations can be justified based on additional information available in any given situation, such as the presence of clear advance directives.25 In the absence of this information, paramedics must apply clinical judgement as to whether they only provide symptom relief or attempt more active interventions, e.g. resuscitation, assisted ventilation.25 This process can be complicated if the patient is not conscious and there are not clear instructions available regarding their wishes.

For an example management summary sheet, click here.

For an example management summary sheet, click here.

Tailoring last days of life care for Māori

Ki te wareware i a tātau tēnei tikanga a tātau, arā te tangi ki ō tātau tūpāpaku, kātahi tō tātau Māoritanga ka ngaro atu i te mata o te whenua ki te Pō, oti atu

If we forget our cultural practices, particularly those pertaining to the dead, then our very essence of our existence as Māori will be lost from the face of this earth, to the underworld forever

For many Māori, it is essential that end of life care recognises the importance of whānau and remains grounded in their tikanga (customs) and kawa (protocols).26 Traditionally, whānau assume the role of pou aroha (care stalwarts) during this process, delivering care that:26

- Is informed by mātauranga Māori (knowledge) passed down from tupuna (ancestors);

- Encompasses all principles of Te Whare Tapa Whā (physical, mental/emotional, family/social and spiritual wellbeing); and

- Recognises a connection with the whenua (land)

However, Māori whānau, hapū and iwi are diverse in their perspectives and traditions, meaning there is no single template for end of life care.27 The general practice team should consider the individualised cultural needs of Māori and their whānau, discuss what is important to them, and prioritise a plan that facilitates such customs.1 In some cases, people and their whānau may benefit from being directed to local Kaupapa Māori health services.

Examples of tikanga/kawa that may be important to Māori in their last days of life:26

- Using te reo Māori (Māori language)

- Incorporating rongoā (traditional healing) including mirimiri (massage)

- Observing tapu (protocols and practices that govern things that are sacred or restricted)

- Observing noa (protocols and practices that return a state of tapu back to its ordinary state)

- Visiting ancestral homes or tūrangawaewae (places where people feel empowered and connected)

- Taking care of personal taonga (treasured objects)

- Including karakia (incantations, prayers, chants)

- Including waiata (songs, singing)

- The presence of Māori Kaumātua (Māori elder) who oversee and provide cultural guidance and support

- Sharing kai (food)

- Observing hygiene principles, e.g. not using a pillow for the head if it has been used elsewhere on the body

- Observing protocols around the removal, retention, return or disposal of any body tissue or substances (no matter how minor they may be perceived, e.g. hair)

For further information on providing culturally informed care at the end of life (including sections for both whānau and health professionals), see: www.teipuaronui.co.nz/

For further information on providing culturally informed care at the end of life (including sections for both whānau and health professionals), see: www.teipuaronui.co.nz/

Once the components of an individualised care plan have been established, the next step is to determine the responsibilities of those involved and frequency of ongoing assessment. While New Zealand guidelines state that health practitioners should undertake regular assessments of the person’s condition,1 the practical capacity to do this in-person (i.e. via home visits) can be a challenge in primary care. In many cases it may be the family/whānau who are providing care and reviewing needs with the support of a community-based nurse (or other health professionals) who will report back to the lead health practitioner.

Te Ara Whakapiri includes a simple home care recording sheet to provide to family/whānau. For access, click here.

Te Ara Whakapiri includes a simple home care recording sheet to provide to family/whānau. For access, click here.

If they are willing, family/whānau should be encouraged to regularly assess and document symptoms and other aspects of wellbeing so that the need for additional support can be identified and provided early.1 This information should be reviewed at least once daily by a member of the healthcare team.10 If it is determined that a person’s condition is deteriorating or new symptoms have emerged, both they and their family/whānau should be involved in conversations about the options for ongoing care.

Practice point: be conscious of changing perspectives following the baseline assessment. As people attempt to process the prospect of impending death, their views concerning cultural and religious beliefs may change.1 Periodically revisit/discuss these concepts and facilitate needs where possible, e.g. by encouraging contact with chaplaincy services or other spiritual providers including Kaiāwhina and/or Kaumātu.

Practice point: be conscious of changing perspectives following the baseline assessment. As people attempt to process the prospect of impending death, their views concerning cultural and religious beliefs may change.1 Periodically revisit/discuss these concepts and facilitate needs where possible, e.g. by encouraging contact with chaplaincy services or other spiritual providers including Kaiāwhina and/or Kaumātu.

Tips for communication with family/whānau1, 5

- An interpreter may be required if there are language barriers

- Provide opportunities to discuss what is important to the person and their family/whānau, particularly spiritual, religious and cultural needs, including after death occurs (see: “Tailoring last days of life care for Māori”)

- Ensure realistic expectations are set, regarding the person’s deteriorating condition, needs and possible requirements involved with delivering care at home, e.g. toileting assistance, changes in mental state

- Consider the level of caregiver distress and if they feel capable of being involved in home care; take time to detail their role in managing symptoms, signs of imminent death and what to do once the person has died

- Communicate any changes in the person’s condition in a manner tailored to their level of health literacy; be conscious that grief may impair their ability to process information

- Be mindful when talking with family/whānau about the person who is dying; do not assume the person cannot hear, even if they have reduced consciousness or appear to be sleeping

Being able to recognise impending signs of death is important to ensure the final moments of life are as comfortable and dignified as possible (Table 1).10 Discussing this information may help the family/whānau to prepare for their loved ones passing, particularly if a healthcare professional will not be present. However, these features do not all occur in every instance or in a specific order.

Table 1. Impending signs of death.10

|

Description

|

Practical advice

(applicable to either health professionals or family/whānau involved in care)

|

|

Sleep

|

People close to death may spend increasing amounts of time in bed or sleeping. It may be more difficult to wake them.

|

- Prioritise communication when the person is most alert but never assume they cannot hear

- Continue talking to them, as appropriate

- Reassure family/whānau that an increasing need for sleep is a natural part of the dying process and not caused by excessive medicine use

|

|

Food and fluids

|

The person may have minimal interest in eating or drinking. Dehydration is usually not a concern as the body typically adapts to the lower fluid intake.

|

- Do not offer food/drink to people if they are unable to swallow

- Ice chips or a straw/sip cup can help a person ingest small amounts of fluid if required. Mouth swabs soaked in water or fruit juice can also help keep the inside of the mouth moist.

- Lip balm or moisturiser can be used to prevent chapped/dry lips

|

|

Skin

|

Skin on the nose, ears, hands and feet may feel cooler. Skin can sometimes appear flushed or may become discoloured or blotchy.

|

- Apply a cool, moist cloth to the forehead

- Have an extra blanket available to provide additional warmth, if required

- Reassure family/whānau that these changes are normal

|

|

Confusion

|

The person may become confused about time, where they are or have trouble identifying familiar people

|

- Talk calmly to the person and provide reassurance; identify yourself by name when speaking with them

- Use a night light

- Keep familiar objects in the room

|

|

Restlessness and agitation

|

More likely when a person becomes semi-conscious. Signs include twitching, plucking at the air or bed clothes, moaning/calling out constantly and trying to get out of bed (even if unable to stand).

|

- Encourage family/whānau to keep sitting and speaking with the person to provide reassurance

- Consider quiet music, radio or aromatherapy

- In some cases the cause may be treatable. Consider whether the person needs their position altered, provide mouth care (e.g. ice chips, water spray, lip balm, cleaning teeth) or help with toileting.

- Clinicians may consider pharmacological treatment, if appropriate, e.g. haloperidol, midazolam

|

|

Loss of bowel and bladder control

|

May occur close to the time of death; often associated with loss of dignity for the person if not sensitively managed

|

- Pre-emptively discuss the possibility of these events occurring and options for management

- Use incontinence products, e.g. pads, pull-ons/wrap-arounds, protection sheets

- Consider catheter use to drain urine, if appropriate

|

|

Noisy breathing

|

Saliva and mucus may build up if the patient becomes too weak to cough or swallow

|

- Reassure family/whānau that this is a normal part of the dying process; it often indicates a transition into deep unconsciousness and is not distressing to the person

- First-line management should be non-pharmacological, e.g. altering the person’s position or turning them on their side if they are congested

- Clinicians may consider pharmacological treatment, if appropriate

|

|

Breathing patterns

|

Breathing may become more irregular as the respiratory system slows

|

- Changes in breathing patterns may be a sign that death is close – notify any family/whānau not present who want to be there at the time of death. However, sometimes these changes may persist for hours or even days before death occurs.

|

|

When death occurs

|

The person will have stopped breathing and be unresponsive. There will be no detectable pulse/heartbeat and facial muscles usually relax, meaning the mouth and eyes may be slightly open. The person's skin will become cooler and paler.

|

- There is no need to rush – it is okay for the family/whānau to spend time with the person

- It is helpful to note the time of death

- An ambulance does not need to be called

- At an appropriate time, the lead health practitioner should be contacted (if not present) so the death can be confirmed and a death certificate written. This can be the next morning if the death occurs during the night.

|

Kua hinga te tōtara i Te Waonui-a-Tāne

The tōtara tree has fallen in Tāne’s great forest

Before the person’s death, family/whānau should be provided with practical advice on what to do when it occurs. This discussion ensures the person’s dignity, respect and wishes will be maintained following death, and allows their loved ones to focus on processing emotions and supporting each other (rather than decision-making).

Key information to provide includes:10

- The features to look for that indicate death has occurred (Table 1). It is helpful to note the time of death.

- There is no need to rush – it is okay to spend time with the person after they die. The family/whānau may also want to contact friends or other relatives to come and say goodbye.

- The lead health practitioner should be contacted so the death can be confirmed and a death certificate written. If the death occurs during the night, the family/whānau can wait until the morning before making contact.

- An ambulance does not need to be called; a funeral director will usually arrange collection of the body/tūpāpaku once contacted by the family/whānau. However, there is no legal requirement to use a funeral director and in some cases family/whānau may choose to co-ordinate the funeral themselves. Ensure the family is aware of all legal obligations, e.g. confirmation of cause of death and registration of the death.

- Keep the room as cool as possible (e.g. turn off heaters and electric blankets); this will help slow the process of decomposition and is particularly important if the person did not want their body/tūpāpaku embalmed following death

- The person’s body/tūpāpaku does not need to be washed. If a decision is made to do this (e.g. for cultural reasons or personal preference), a sponge can be used on the skin/face, medical/nursing equipment removed, dentures and glasses replaced if wished, and the person dressed in favourite clothes. The family/whānau should be advised that the person’s body/tūpāpaku will become increasingly stiff over time, so any movement or repositioning should not be excessively delayed.

For more comprehensive information and advice for family/whānau on what to do once a death occurs at home and advice for processing emotions, click here

For more comprehensive information and advice for family/whānau on what to do once a death occurs at home and advice for processing emotions, click here

For search tools to help family/whānau find local funeral services, click here (Funeral Directors association of NZ) or here (NZ Independent Funeral Homes)

For search tools to help family/whānau find local funeral services, click here (Funeral Directors association of NZ) or here (NZ Independent Funeral Homes)

To access the Death Documents website (a digital tool enabling practitioners to complete and view the Medical Certificate of Cause of Death and Cremation Forms), click here

To access the Death Documents website (a digital tool enabling practitioners to complete and view the Medical Certificate of Cause of Death and Cremation Forms), click here

Assessing family/whānau bereavement risk

Once death occurs, the care team’s involvement continues as family/whānau may require further support. This might involve an ongoing active role for the general practitioner and/or nurse(s) if the family/whānau are enrolled with the same practice, or if they are not, enquiring whether their needs are being considered by another care provider.

A loved one’s death can be one of the most challenging events that family/whānau experience. While many people process grief and integrate their loss, others have significant difficulty adjusting to their bereavement.28 This challenge can be compounded if there is an abrupt discontinuation of contact with the person’s general practice team or lack of follow-up.29

It is recommended to discuss bereavement support and ensure a risk assessment is conducted for all family/whānau members who wish to have one (see link below).1 For family/whānau assessed as being at low bereavement risk, it is usually sufficient to provide written resources (e.g. a brochure or website) and to have a general discussion about the spectrum of emotions that can be experienced. Most will adjust in time with the support of their friends and family/whānau.28 However, more active intervention(s) may be required for people with multiple bereavement risk factors (e.g. high levels of anger or guilt, a lack of social support).1 People can be directed to a local bereavement support agency or specialist support, e.g. from a counsellor or hospice bereavement service. Many funeral director services also offer bereavement support.

To access the “Te Ara Whakapiri Bereavement Risk Assessment Tool”, click here.

To access the “Te Ara Whakapiri Bereavement Risk Assessment Tool”, click here.

Further resources:

Acknowledgement

Thank you to the following experts for review of this article:

- Dr Kate Grundy, Palliative Medicine Physician, Clinical

Director of Palliative Care, Christchurch Hospital Palliative

Care Service and Clinical Lecturer, Christchurch School of

Medicine

- Vicki Telford, Clinical Nurse Specialist, Nurse Maude

Hospice Palliative Care Service, Christchurch

- Dr Helen Atkinson, General Practitioner and Medical

Officer, Harbour Hospice

- Dr Robert Odlin, General Practitioner, Orewa Medical

Centre

- Fraser Watson, Extended Care Paramedic Clinical Lead,

Hato Hone St John

N.B. Expert reviewers do not write the articles and are not responsible for the final content.

bpacnz retains editorial oversight of all content.

This resource is the subject of copyright which is owned by bpacnz.

You may access it, but you may not reproduce it or any part of it except in the limited situations described in the

terms of use on our website.

Article supported by Te Aho o Te Kahu, Cancer Control Agency.

References

- Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. Te Ara Whakapiri: Principles and guidance for the last days of life. 2017. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/te-ara-whakapiri-principles-guidance-last-days-of-life-apr17.pdf (Accessed September, 2023).

- Cottrell L, Duggleby W. The “good death”: an integrative literature review. Palliat Support Care 2016;14:686–712. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951515001285

- Sagha Zadeh R, Eshelman P, Setla J, et al. Strategies to improve quality of life at the end of life: interdisciplinary team perspectives. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2018;35:411–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909117711997

- Palliative Care Council of New Zealand. National health needs assessment for palliative care phase 2 report: palliative care capacity and capability in New Zealand. 2013. Available from: https://www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/assets/Publications/Palliative/national-health-needs-assessment-for-palliative-care-jun13.pdfhttps://www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/assets/Publications/Palliative/national-health-needs-assessment-for-palliative-care-jun13.pdf (Accessed September, 2023).

- Wyatt K, Bastaki H, Davies N. Delivering end‐of‐life care for patients with cancer at home: Interviews exploring the views and experiences of general practitioners. Health Soc Care Community 2022;30. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13419

- South Island Alliance. Te Ara Whakapiri. 2020. Available from: https://www.sialliance.health.nz/programmes/palliative-care/te-ara-whakapiri/ (Accessed September, 2023).

- Siddall PJ, MacLeod RD. Physical, psychological/psychiatric, social, and spiritual problems and symptoms. In: MacLeod RD, Van den Block L, eds. Textbook of Palliative Care. Cham: Springer International Publishing 2018. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31738-0_9-1

- Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. Māori health models – Te Whare Tapa Whā. 2017. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/populations/maori-health/maori-health-models/maori-health-models-te-whare-tapa-wha (Accessed September, 2023).

- Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. Advance care planning: A guide for the New Zealand health care workforce. 2011. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/advance-care-planning-aug11.pdf (Accessed September, 2023).

- Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. Te Ara Whakapiri Toolkit: care in the last days of life. 2017. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/te-ara-whakapiri-toolkit-apr17.pdf (Accessed September, 2023).

- National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK). Recognising when a person may be in the last days of life (chapter 5). In: Care of Dying Adults in the Last Days of Life. 2015. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK356012/ (Accessed September, 2023).

- McKinlay E, Vaipuna K, O’Toole T, et al. Doing what it takes: a qualitative study of New Zealand carers’ experiences of giving home-based palliative care to loved ones. N Z Med J 2021;134:21–32.

- Lindqvist O, Tishelman C, Hagelin CL, et al. Complexity in non-pharmacological caregiving activities at the end of life: an international qualitative study. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001173. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001173

- Shin J, Chang YJ, Park S-J, et al. Clinical practice guideline for care in the last days of life. Korean J Hosp Palliat Care 2020;23:103–13. https://doi.org/10.14475/kjhpc.2020.23.3.103

- Morgan NA, Rowett D, Currow DC. Analysis of drug interactions at the end of life. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5:281–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000767

- Wilson E, Morbey H, Brown J, et al. Administering anticipatory medications in end of life care: A qualitative study of nursing practice in the community and in nursing homes. Palliat Med 2015;29:60–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216314543042

- MacLeod R, Macfarlane S. The palliative care handbook. Ninth edition. 2019. Available from: https://www.waipunahospice.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Palliative-Care-Handbook-2018.pdf (Accessed September, 2023).

- Mercy Hospice Auckland. Syringe driver handbook. 2016. Available from: https://healthify.nz/assets/syringe-driver-handbook.pdf (Accessed September, 2023).

- Brisbane South Palliative Care Collaborative. A practical handbook for health professionals: How to safely set up, commence and provide necessary documentation for NIKI T34TM, T34TM and BodyGuardTM T syringe pump infusions. 2022. Available from: https://www.caresearch.com.au/portals/10/Documents/NIKI-BodyGuard-pump-handbook-WEB-update-FINAL.pdf (Accessed September, 2023).

- Peralta T, Castel-Branco MM, Reis-Pina P, et al. Prescription trends at the end of life in a palliative care unit: observational study. BMC Palliat Care 2022;21:65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-00954-z

- Diabetes UK. End of life guidance for diabetes care. 2021. Available from: https://diabetes-resources-production.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/resources-s3/public/2021-11/EoL_TREND_FINAL2_0.pdf (Accessed September, 2023).

- Carter AN. To what extent does clinically assisted nutrition and hydration have a role in the care of dying people? J Palliat Care 2020;35:209–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0825859720907426

- Sinclair S, Lever N. Heart rhythm New Zealand position statement: management of implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) and pacemakers for patients nearing end of Life. Final version August 2014. Available from: https://thinkhauorawebsite.blob.core.windows.net/websitepublished/CCP/Resources/Palliative%20Care/EOL%20%20ICD%20Pacemaker.pdf (Accessed September, 2023).

- Benjamin MM, Sorkness CA. Practical and ethical considerations in the management of pacemaker and implantable cardiac defibrillator devices in terminally ill patients. Bayl Univ Med Cent Proc 2017;30:157–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2017.11929566

- Anderson NE, Robinson J, Moeke-Maxwell T, et al. Paramedic care of the dying, deceased and bereaved in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Prog Palliat Care 2021;29:84–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/09699260.2020.1841877

- Moeke-Maxwell T, Mason K, Toohey F, et al. Pou Aroha: an indigenous perspective of Māori palliative care, Aotearoa New Zealand. In: MacLeod RD, Van den Block L, eds. Textbook of Palliative Care. Cham: Springer International Publishing 2019. 1247–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77740-5_121

- Moeke-Maxwell T, Wharemate R, Black S, et al. Toku toa, he toa rangatira: A qualitative investigation of New Zealand Māori end of life care customs. Int J Indig Health 2018;13:30–46. https://doi.org/10.32799/ijih.v13i2.29749

- Sealey M, O’Connor M, Aoun SM, et al. Exploring barriers to assessment of bereavement risk in palliative care: perspectives of key stakeholders. BMC Palliat Care 2015;14:49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-015-0046-7

- Roberts KE, Jankauskaite G, Slivjak E, et al. Bereavement risk screening: A pathway to psychosocial oncology care. Psychooncology 2020;29:2041–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5526