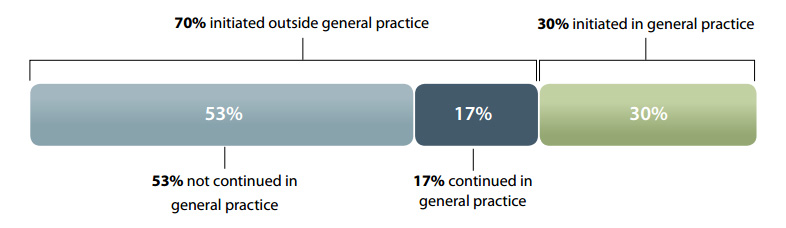

The volume of oxycodone prescribed in New Zealand is continuing to rise, despite efforts to encourage clinicians to use this medicine appropriately. Approximately 30% of oxycodone is initiated within general practice. A further 17% of prescriptions are continued by General Practitioners, when initiated outside general practice. Knowledge of a patient’s clinical and medicines history and psychosocial background puts General Practitioners in a strong position to not simply “go with the flow”, but instead re-evaluate the indication for oxycodone.

In this article

View / Download pdf version of this article

Update: Oxycodone: how did we get here and how do we fix it? (BPJ62)

Approximately 70% of people dispensed oxycodone in New Zealand are initiated on this medicine outside

of general practice, i.e. by a doctor in secondary care. This supports the claim that much of the use of

oxycodone is driven by secondary care prescribing. However, 30% of all prescriptions for oxycodone are

initiated by a General Practitioner. In addition 17% of patients initiated on oxycodone in secondary care

have their prescriptions continued by a General Practitioner. Oxycodone is a strong opioid indicated for

the treatment of moderate to severe pain, when morphine is not tolerated, and all other options have

been considered. Clinicians are urged to assess whether oxycodone is appropriate whenever initiating or

continuing a prescription for this medicine.

Figure 1: Source of prescriptions for patients initiated on oxycodone in 2011 (Pharmaceutical Warehouse dispensings)

Why is oxycodone a problem?

Oxycodone is not a new medicine. It was first synthesised

in 1916 in Germany and became available for clinical use

in the United States by 1939. For many years it has been

used overseas as a component in combination short-acting

analgesics. A controlled release formulation of oxycodone

alone was released in the United States in 1996 and was in New

Zealand by 2005. Since then, use of this medicine has increased

dramatically and many countries are now dealing with issues

of misuse, addiction and illegal diversion of prescriptions.

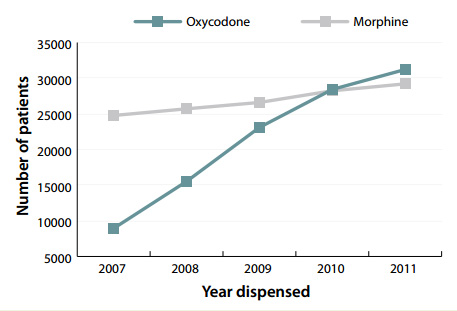

Figure 2: Number of patients dispensed oxycodone and morphine 2007-11 (Pharmaceutical Warehouse dispensings)

In New Zealand, the use of oxycodone has increased by

249% over the last five years (Figure 2). This has not been

accompanied by a corresponding decrease in prescriptions for

morphine, and the total amount of strong opioids dispensed

is climbing rapidly.

This raises several questions:

- Which patients are being prescribed oxycodone? And by

whom?

- Has the marketing of oxycodone been so effective that

a whole new group of patients now “require” strong

opioids?

- Is oxycodone being inappropriately prescribed instead of

analgesics that are lower on the WHO pain ladder? If so,

why?

We encourage every clinician to look critically at their

prescribing of oxycodone and, if necessary, make changes

on how they prescribe this medicine.

What is the appropriate indication for oxycodone?

There is no dispute that oxycodone is an effective analgesic,

however, prescribing figures suggest that it is being chosen as

the first-line opioid in many situations when it should not be.

Morphine is the preferred first-line option for the treatment

of acute and chronic moderate to severe pain, when a strong

opioid is indicated. When compared to morphine, oxycodone:

- Has no better analgesic efficacy

- Has a similar adverse effect profile

- May have more addictive potential1,2

- Is significantly more expensive

Oxycodone should only be prescribed for the treatment

of moderate to severe pain in patients who are intolerant

to morphine and when a strong opioid is the best option.

Although oxycodone has been reported to be potentially

safer than morphine in patients with renal impairment, active

metabolites can still accumulate.3 Fentanyl or methadone are

likely to be safer in patients with renal impairment, who require

a strong opioid, because they have no clinically significant

active metabolites.3 Discussion with a pain or renal physician is

recommended when considering the use of any strong opioid

in a patient with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance

< 30 mL/min).

For further information see:

For further information see:

Oxycodone misuse in New Zealand

The Illicit Drug Monitoring System (IDMS) provides

surveillance on the misuse of drugs in New Zealand.

Oxycodone was first noted as an emerging drug of

misuse by the IDMS in 2008. The latest report (to the

end of 2010) shows that oxycodone is continuing to

feature prominently amongst people who misuse

drugs. Oxycodone was the second most common new

drug to be used in 2010 by methamphetamine users,

behind synthetic cannabis (which is now unavailable for

commercial sale). In 2010, 18% of injecting drug users had

illicitly used oxycodone in the past six months, compared

to 9% in 2008.4 Pharmaceutical morphine remains one

of the principal opioids used by injecting drug users in

New Zealand (along with “homebake” heroin/morphine

and methadone).4 The available supply of diverted

opioids is directly related to the total amount of opioids

prescribed.5

Although other controlled release opioids can also be

tampered with, the controlled release form of oxycodone

(OxyContin), is rapidly gaining popularity as a drug of

misuse. There has been criticism that the information

warning patients not to break, chew or crush the tablets

to avoid rapid release and absorption of a potentially

harmful dose of oxycodone, may have actually instructed

people in how to misuse the medicine.6,19 In response

to this problem in the United States and Canada, the

controlled release formulation has been replaced by a

newer extended release formulation (OxyNeo) aimed to

be tamper-resistant.7,8 In Canada from 2013, a special

application will be required for patients to access

oxycodone, unless they are being treated for cancer pain

or palliative care.8 No changes to prescribing regulations

or medicine formulation have been announced for New

Zealand or Australia.

What can General Practitioners do to reduce

oxycodone use?

Data from the Pharmaceutical Warehouse show that 30%

of prescriptions for oxycodone are initiated within general

practice (Figure 1). When considering initiation of oxycodone,

always ask yourself if you would use morphine for this patient. If

the answer is no then do not prescribe oxycodone. Oxycodone

should not be prescribed when a weaker opioid, e.g. codeine,

dihydrocodeine or tramadol, would be more appropriate.

Remember that: 5 mg oxycodone is approximately equivalent

to 10 mg morphine, 50 - 100 mg tramadol, 100 mg

dihydrocodeine or 100 mg codeine.9,10

Best Practice Tip: Make it a practice policy, whenever

prescribing a strong opioid, to record why the patient has been

prescribed this medicine, the usual dose, the expected time

frame for treatment, any concerns regarding the patient (such

as low mood, poor social support) and specific instructions

regarding actions if an increased dose is requested, an early

prescription is sought, or if medicines are reported as lost.

Best Practice Tip: Make it a practice policy, whenever

prescribing a strong opioid, to record why the patient has been

prescribed this medicine, the usual dose, the expected time

frame for treatment, any concerns regarding the patient (such

as low mood, poor social support) and specific instructions

regarding actions if an increased dose is requested, an early

prescription is sought, or if medicines are reported as lost.

Patients on oxycodone initiated in secondary care

Approximately 70% of oxycodone is initiated within secondary

care. Prescribing data show that when oxycodone is initiated

from outside general practice, 17% of patients have their

prescription continued by a General Practitioner (Figure 1).

Knowledge of a patient’s clinical and medicines history and

psychosocial background puts General Practitioners in a

strong position to not simply “go with the flow”, but instead

re-evaluate the indication for oxycodone, even if it has been

initiated within secondary care.

Summary: management strategies for patients

discharged on oxycodone

When a patient is discharged from secondary care on

oxycodone, a suggested management strategy is as

follows:

- When the patient presents for a renewal of a

prescription of oxycodone, assess their level of

pain and consider whether a strong opioid is

still required.

- If a strong opioid is no longer required, step

down to a weaker opioid or to paracetamol.

Depending on the length of time the patient

has been on oxycodone, a gradual tapering of

the dose may be necessary.

- If a strong opioid is still required, consider

changing the patient to morphine. Explain to

the patient that morphine is equally effective,

will not usually result in any other adverse

effects and that it is the preferred option when

strong opioids are used in general practice.

Regularly reassess the patient and step-down

treatment as appropriate.

Make sure the patient knows that oxycodone is a strong

opioid

Many patients are unaware (and shocked to be told) that

oxycodone is a strong opioid similar to morphine, but milligram

for milligram, twice as potent. Both patients and clinicians

have been known to mistakenly associate oxycodone with the

weak opioid codeine, rather than with morphine, because of

the similarity in the names of the medicines.

Reassess why oxycodone was initially prescribed

Establish the precise clinical problem for which oxycodone

was initially prescribed, e.g. post-surgical pain or an acute

injury. Does this same problem exist now? Most patients can

gradually reduce analgesia in the days to weeks after surgery

or acute injury.

What level of pain is the patient experiencing?

If there is an ongoing medical condition that requires analgesia,

check that the level of pain being experienced warrants the

use of a strong opioid.

Consider if oxycodone can be stopped

If the pain has reduced and oxycodone is no longer required,

stop or taper the dose (next section). Weaker analgesia, such as

codeine and paracetamol, may still be required. Tramadol

and dihydrocodeine can also be used as alternatives. Check

the patient’s understanding of any analgesic medicines that

are used - are they being taken at the right time and in the

right dose to gain effective pain relief and to minimise adverse

effects?

Consider switching the patient to morphine

If a strong opioid analgesic is still indicated, consider switching

the patient to morphine. Morphine should be the strong opioid

of choice for the majority of patients unless they are allergic to

morphine or intolerant to its adverse effects. A dose of 5 mg

of controlled release oxycodone is approximately equivalent

to 10 mg of long-acting morphine. This conversion rate is,

however, only approximate and there is varying guidance on

the dose of morphine that should be used when switching.9,10

If the aim is to eventually discontinue opioids and the degree

of pain allows, calculate the equivalent dose of morphine and

then start the patient on half of this dose.2 The response of

the patient to the change in medicine should be reviewed

regularly and the dose adjusted as required to prevent any

withdrawal symptoms. The “ABC” of opioid pain medicine use

should be remembered:

- Anti-emetic prescription if nausea present

- Breakthrough dose of morphine may be required

- Constipation is likely, prescribe a laxative

Detecting aberrant drug taking

behaviour

Behaviours that may suggest the development of

aberrant drug taking behaviour, such as overuse, hoarding,

dependence and diversion, include: presenting early for

repeats, loss of prescriptions or medicines or requests for

an escalation in dose.

Patients with chronic pain who take opioid medicines

may over time become tolerant or dependent and require

increased doses to enable them to function day to day.6 If

the patient reports that their pain is worsening, consider if

this would normally be expected with the condition being

treated, if a different diagnosis should be considered or

whether there is the possibility of misuse.

Addiction to opioids is reported to occur in only a small

number of patients with chronic pain. However, many

more patients with chronic pain display aberrant drug

taking behaviour.12,13

Personal or family history of alcohol or drug dependence

increases the risk of misuse of opioids. The presence of

an anxiety disorder or depression further increases this

risk.14,15 However, patients who misuse medicines do not

always fit a stereotype and risk factors may not always

be apparent. Any person, regardless of gender, age,

ethnicity, income, health or employment status can be

at risk of aberrant drug taking behaviour. It is therefore

recommended that every patient who is prescribed

an opioid is assessed for risk factors for aberrant drug

taking behaviour, including the possibility of diversion of

prescriptions.

If an opioid is continued, establish a pattern of regular

review

Every patient prescribed a strong opioid analgesic on an

ongoing basis requires regular review. The requirement

for monthly prescriptions for opioids provides an ideal

opportunity to review the need for the medicine, however, in

some situations review will need to be more frequent, such as

early in the course of treatment. Discuss the dose, the goals

of treatment, adverse effects, the time frame for the use of

opioid and if appropriate develop a clear plan for stopping the

medicine. Check with the patient how they are managing day

to day. The Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists

recommends a “5A assessment” when prescribing a strong

opioid: assess the patient’s analgesia, activity, adverse effects,

affect and aberrant drug taking behaviour (see “Detecting

aberrant drug-taking behaviour”).11 Referral to a specialist

pain clinic may be required if the patient’s pain is unable to

be effectively controlled or if there are other concerns with

aspects of the “5A” assessment.

How to discontinue oxycodone

Abrupt cessation

Patients who have been taking oxycodone at low doses

(e.g. 10 - 20 mg daily) for less than one to two weeks

can generally stop the medicine without experiencing

withdrawal symptoms.16 Gradual tapering of oxycodone to

avoid withdrawal symptoms is recommended in most other

situations.

Gradual dose reduction

Patients who have been taking oxycodone for more than one

to two weeks, or at high doses, should have the dose gradually

tapered to avoid symptoms of opioid withdrawal.2,6

How quickly and by how much the oxycodone can be reduced

will depend on the current dose, the length of time the

medicine has been taken for and individual patient factors,

such as anxiety, co-morbidities (e.g. depression or other

psychiatric conditions) and the likelihood that the patient is

dependent on oxycodone, in which case the dose should be

reduced more slowly.2,6

Advice about tapering of opioids varies widely in the literature,

however, in general: 2,6,16

Reduce the dose in 20-25% increments or, if required,

more slowly by 5-10%

Reductions can be made every two or three days

Once the patient has been reduced to one-third of the

initial dose, the rate of taper should be slowed

Consider holding the dose at the same level if the patient

develops withdrawal symptoms, an increase in pain or

lowered mood

Most patients can be withdrawn from oxycodone within

one month, depending on how high the dose was prior

to initiating tapering

Referral to addiction services

In some situations it may be more appropriate to refer patients

to a community based drug and alcohol programme, to

withdraw from oxycodone. Patients who may benefit from

referral include those who:17

- Are unable to be slowly tapered off oxycodone in general

practice due to factors such as a lack of success with

tapering, non-compliance with tapering, accessing

opioids from other sources

- Are misusing oxycodone or other addictive substances

(including alcohol)

Opioid withdrawal symptoms

Abrupt cessation of any strong opioid can produce

extremely unpleasant and distressing withdrawal

symptoms, depending on the dose and the length of

time the medicine has been used for.18 These symptoms

reach a peak approximately three days after the opioid

is stopped and may last for approximately 7-10 days.19

Although opioid withdrawal is very unpleasant for the

patient, it is not usually associated with a risk of seizure

or delirium, unlike abrupt cessation of such substances as

alcohol or benzodiazepines.18,19

Opioid withdrawal symptoms can include insomnia,

dysphoria, yawning, rhinorrhoea, piloerection,

perspiration, lacrimation, tremors, restlessness, poor sleep,

nausea or vomiting, diarrhoea, muscle aches and twitches,

abdominal cramps, anxiety and an increase in pain.6,16

If required, medicines that may assist with the treatment

of withdrawal symptoms include:

- Clonidine which decreases adrenergic activity

and may relieve symptoms such as nausea,

sweating, cramps and tachycardia: oral dose 50-75

micrograms up to three times a day, or alternatively

a transdermal patch may be used if there are

concerns about adherence to oral dose

- A sedating antihistamine may help if the patient is

restless and unable to sleep

The role of strong opioids for chronic non-cancer pain

The use of strong opioids for chronic non-cancer pain is controversial and there is limited quality evidence to support or oppose their use for this type of pain.11,12 Principles for the use of opioid analgesics in people with chronic non-cancer pain have been developed by the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists.11 The principles aim to take into account both the widely varying individual response to opioids and the risks for an individual patient. The use of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain should be regarded as an “ongoing individual trial of therapy”.11

Assess all aspects of the pain

Consider factors that may influence the nature and intensity of pain and the patient’s reaction to the pain. Ask about the patient’s beliefs about the underlying problem, their mood, their fears and their expectations of pain treatment. Discuss the goals of treatment with the patient - a reduction in pain and an increase in function are realistic and achievable outcomes, while an expectation that the pain will be totally eliminated may be unrealistic.17,20

Pain can be difficult to assess because it is subjective and is often influenced by factors such as mood, stress and the psychosocial support that the patient has. The most clinically useful pain scales include an assessment of the impact of the pain on daily life. Pain can have a significant effect on daily activities, e.g. altering sleep or appetite. It can induce or exacerbate depression and anxiety, it can influence social interactions, prevent work and impair relationships.

For further information about pain scales, see “Pharmacological management of chronic pain”, BPJ 16 (Sep, 2008).

For further information about pain scales, see “Pharmacological management of chronic pain”, BPJ 16 (Sep, 2008).

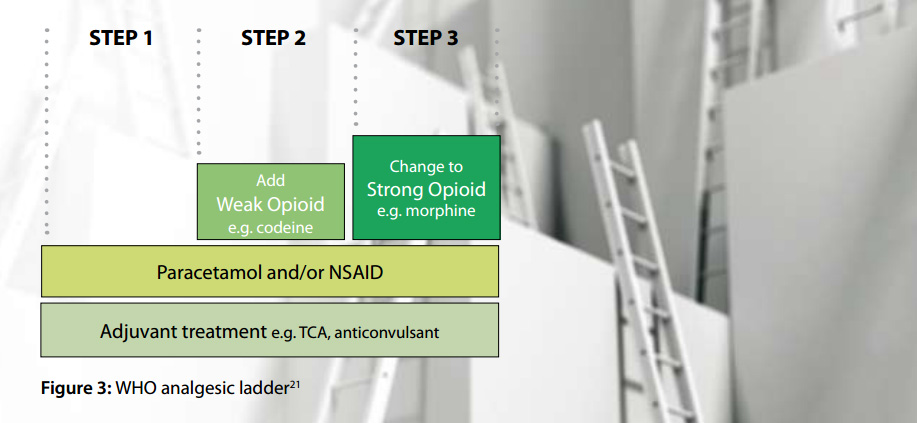

Ensure there has been an adequate trial of other treatments

The WHO analgesic ladder provides a step-wise approach to analgesia for the management of pain (Figure 3).21 Adjuvant treatments such as tricyclic antidepressants and anticonvulsants, can be included at every step of the ladder, especially for patients with neuropathic pain, and it is recommended that they are considered before the use of strong opioids, i.e. Step 3.11 Non-pharmacological treatment of pain is also important. This includes ensuring that the patient understands the underlying problem and the treatment plan, checking on family and social supports, promoting the benefit of healthy lifestyle choices (e.g. exercise, adequate sleep, balanced diet) and the involvement of other health professionals, e.g. physiotherapist, occupational therapist, psychologist, pain clinic specialist.

Consider if a strong opioid is indicated and appropriate for the patient

Prior to initiating a strong opioid for chronic pain in particular, consider the following questions:

- Have I identified the cause of the pain?

- What am I trying to achieve?

- Is this what the patient wants?

- To what extent are psychosocial factors contributing to the pain level and how can these factors be addressed?

- Is there evidence that a particular medicine will help this type of pain?

- Are there non-pharmacological alternatives?

- Do the potential benefits outweigh the harms of the treatment? Check if the patient has a history of addictive behaviour, alcohol or medicine misuse. If the patient has a current or past history of a psychological problem, a strong opioid may not be appropriate.

- Have I provided effective education about the most appropriate way to use analgesics?

- Have I considered how long a strong opioid may be required for?

- Have I made a plan for follow up?

Reach an agreement with the patient regarding a trial of strong opioid analgesic

If a strong opioid is indicated, ensure the patient has a good understanding of the type of medicine to be used and the goals of treatment, i.e. an increase in function rather than complete resolution of pain. The patient should be made aware of the potential problems with strong opioids, including adverse effects, safety issues and the potential for dependency and misuse. It is also recommended that an agreement is reached so that if the goals are not achieved, adverse effects are intolerable or there are concerns about misuse, the opioid will be discontinued.11,20 Any agreement should be clearly documented in the patient notes. This should include guidance about management if the patient requests or presents for an early repeat, if the medicine is reported as lost or there is a request for an increase in dose. When a strong opioid is prescribed, ideally there should be one prescriber and one pharmacy involved.

Start with an appropriate dose and slowly titrate as required

Choose a low starting dose of a long-acting or extended release preparation of a strong opioid, usually morphine as the first-line choice. Most patients taking opioids will also require a laxative, and possibly an anti-emetic (in the initial stages of treatment), as well as short-acting medicine for breakthrough pain. It is recommended that the dose be slowly titrated over several weeks if required, with a clinical assessment prior to each increase in dose. The Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists recommends a “5A” assessment which includes a review of:11

- Analgesia

- Activity

- Adverse effects

- Affect

- Aberrant behaviour

A suggested time frame for a trial of a strong opioid is four to six weeks.

9 If the treatment has been of no benefit after this time, the dose of the opioid should be tapered and then stopped.

Regularly review the patient

Once the patient is established on an effective dose, regularly reassess them using the “5A” assessment. Check that the goals of treatment agreed initially are being achieved and that a strong opioid is still the most appropriate medicine for the patient. If the patient requests an increase in dose consider whether this may reflect:

- A change in the underlying condition producing pain

- The patient’s current mood, life stressors or other social circumstances

- The development of tolerance

- Opioid induced hyperalgesia (abnormal sensitivity to pain due to prolonged use of strong opioids)20

- Aberrant drug taking behaviour

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Thank you to Dr Geoff Robinson, Chief Medical Officer, Addiction Medicine Specialist, Capital & Coast DHB and Dr Howard Wilson, General Practitioner and Pharmacologist, Canterbury, members of the analgesic subcommittee of the Pharmacology and Therapeutics Advisory Committee to PHARMAC for expert guidance in developing this article.

References

- Zacny JP, Lichtor SA. Within-subject comparison of the psychopharmacological profiles of oral oxycodone and oral morphine in non-drug-abusing volunteers. Psychopharm 2008;196:105-16.

- Kahan M, Mailis-Gagnon A, Wilson L, Srivastava A. Canadian guideline for safe and effective use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain. Clinical summary for family physicians. Part 1: general population. Can Fam Physician 2011;57:1257-66.

- King S, Forbes K, Hanks GW, et al. A systematic review of the use of opioid medication for those with moderate to severe cancer pain and renal impairment: A European Palliative Care Research Collaborative opioid guidelines project. Palliat Med 2011;25(5):525-52.

- Wilkins C, Sweetsur P, Smart B, Griffiths R. Recent trends in illegal drug use in New Zealand, 2006-2010. Findings from the 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 and 2010 Illicit Drug Monitoring System (IDMS). Auckland: Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation (SHORE), School of Public Health, Massey University, 2010.

- Wilkins C, Sweetsur P, Griffiths R. Recent trends in pharmaceutical drug use among frequent injecting drug users, frequent methamphetamine users and frequent ecstasy users in New Zealand, 2006-2009. Drug and Alcohol Review 2011;30:255-63.

- Manubay JM, Muchow C, Sullivan MA. Prescription drug abuse: epidemiology, regulatory issues, chronic pain management with narcotic analgesics. Prim Care Clin Offic Pract 2011;38:71-90.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA approves new formulation for OxyContin. FDA news release. 5th April 2010. Available from: www.fda.gov (Accessed May 2012).

- Ministry of Health and Long-term Care. Change in funding status of oxycodone controlled release tablet (discontinuation of OxyContin and introduction of OxyNEO). Available from: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/drugs/ons/oxy_faq.aspx (Accessed May, 2012).

- Australian Medicines Handbook Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd, 2011.

- British National Formulary (BNF) 62. London: Pharmaceutical Press, 2011.

- Faculty of Pain Medicine. Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. 2010. Principles regarding the use of opioid analgesics in patient with chronic non-cancer pain. Available from: www.fpm.anzca.edu.au (Accessed May, 2012).

- Manchikanti L, Fellows B, Ailinani H, Pampati V. Therapeutic use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids: a ten-year perspective. Pain Physician 2010;13:401-35.

- Fishbain DA, Cole B, Lewis J, et al. What percentage of chronic non-malignant pain patients exposed to chronic opioid analgesic therapy develop abuse/addiction and/or aberrant drug-related behaviours? A structured evidence-based review. Pain Med 2008;9(4):444-59.

- Monheit B. Prescription drug misuse. Aust Fam Physician 2010;39(8):540-6.

- Ling W, Mooney L, Hillhouse M. Prescription opioid abuse, pain and addiction: clinical issues and implications. Drug Alcohol Rev 2011;30:300-5.

- Gordon D, Dahl J. Opioid withdrawal, #95, 2nd edition. J Pall Med 2011;14(8):965-6.

- Kahan M, Wilson L, Mailis-Gagnon, Srivastava A. Canadian guideline for safe and effective use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain. Clinical summary for family physicians. Part 2:special populations. Can Fam Physician 2011;57:1269-76.

- Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG et. al. Opioid treatment guidelines. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain 2009;10(2):113-30.

- Department of Health and Community Services, Newfoundland and Labrador. Oxycontin Task Force, Final report. June 30, 2004. Available from: www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/publications/oxycontin_final_report.pdf (Accessed May, 2012).

- British Pain Society. Opioids for persistent pain: good practice. A consensus statement prepared on behalf of the British Pain Society, the Faculty of Pain Medicine of the Royal College of Anaesthetists, the Royal College of General Practitioners and the Faculty of Addictions of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. January 2010. Available from: www.britishpainsociety.org (Accessed May, 2012).

- WHO analgesic ladder. Available from: www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/ (Accessed May, 2012).