What to expect inside the mouth

Teething pain |

Gingivitis,

oral thrush,

angular

cheilitis,

eruption cysts,

gum boils,

ulcers,

herpes

simplex virus |

Non-nutritive sucking,

mouth breathing,

bruxism |

Fraenal

attachments,

“tongue-tie” |

Tooth trauma

In order to recognise abnormal oral health in children, it is important to understand the normal pattern of tooth development

and appearance of the mouth.

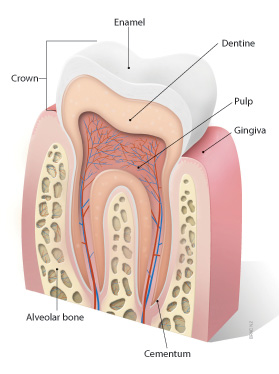

Anatomy of the tooth

Teeth begin to develop from approximately the sixth week in utero. As the child grows, twenty primary (deciduous) teeth

form, erupt and shed and are replaced by 32 permanent teeth. Tooth development is influenced by both genetic and environmental

factors.1

Each tooth has roots in the alveolar bone of the maxilla or mandible with a visible crown that emerges from the gingiva.

The tooth is held in place, in the gingiva, by the periodontal membrane. The four components of teeth are enamel, dentine,

pulp and cementum.1

Dental enamel protects the tooth from fracture and wear and is not regenerated once damaged.1

Dentine forms the structure of the tooth and is produced by the dental pulp which is a specialised tissue responsible

for the neurosensory function and reparative potential of teeth. Reparative dentine is formed in response to environmental

stimuli such as trauma, tooth wear or caries.1

Cementum is structurally similar to bone and covers the root surface. If cementum is lost the tooth root may become

fused to or resorbed by the alveolar bone.1

Tooth eruption

The eruption of primary teeth (teething) usually begins between age six and ten months. The front incisors are most

commonly the first teeth to erupt, followed by the first primary molar, canines and second primary molars. Tooth eruption

is usually bilaterally symmetrical i.e. the left and right teeth appear at similar times. All primary teeth have usually

erupted by age 30 months, although this can depend on gender and ethnicity, e.g., girls tend to develop teeth earlier

than boys and European children tend to develop teeth later than some other ethnicities.1

Permanent teeth develop behind the primary teeth in the alveolar bone. As the permanent tooth grows towards the surface,

it resorbs the root of the primary tooth, causing it to loosen and fall out. Permanent teeth usually start to emerge at

around six years of age. Occasionally the primary tooth remains beside the permanent tooth, but in most cases it will

drop out, without treatment, within one year.1

Abnormal teeth development sometimes indicates a systemic health problem e.g. hypothyroidism. If a child loses primary

teeth before the age of four years, has asymmetrical primary or permanent tooth eruption, or eruption is delayed by more

than six months after expected, they should be referred to a dentist or paediatrician.

Accelerated primary or permanent tooth eruption may occur in children who are obese, and delayed eruption may occur

in those who were born pre-term.1

See below for information about the management of teething

pain

See below for information about the management of teething

pain

Appearance of the teeth and gums

Lift the lip

Start to look in the child’s mouth as soon as the first tooth erupts. Examine the teeth, gingiva, tongue and oral

cavity for abnormalities.

Normal gingiva is reddish pink, smooth, firm and resilient. A slight rolling or rounding at the neck of the tooth is

normal. The crown of the tooth should not be excessively covered with gingiva.2

Abnormalities to look for include swelling, redness, bleeding or recession of the gingiva, change in tooth position,

premature tooth mobility or tooth loss and heavy plaque or calculus deposits, which are often seen on the outer surface

of the incisors and the inner surface of the molars.2

Chalky white spots on the teeth enamel may indicate areas of demineralisation which is an early sign of dental caries.

Tooth decay

Tooth decay is a multifactorial disease in which susceptible tooth surfaces, acidogenic bacteria, saliva, dietary

factors and access to fluoride all play a role. A risk factor in young children is constant snacking or grazing and frequent

consumption of sugary or starchy foods. Attention to dietary habits, teeth cleaning, plaque removal and fluoride toothpaste

promote remineralisation. If there is no intervention, caries will progress.3

Basic oral hygiene messages for parents

Start brushing teeth as soon as they emerge from the gum

Tooth brushing should begin as soon as the first tooth emerges from the gum. Use a smear of fluoride toothpaste

on a soft, clean cloth or a child-sized toothbrush when the infant is older. This can be increased to a pea-sized amount

of toothpaste after six years of age. Instruct the child to spit but not rinse, as fluoride works topically.

N.B. Normal strength toothpaste can be used for children. It is not advised to use “junior” toothpaste

which has a lower fluoride content.

Teeth should be brushed for two minutes, twice a day - after breakfast and before bed. When the child can control a

pencil and begin to write, they can hold their own toothbrush, however brushing should be supervised until the child

is eight to ten years old.6

Flossing once a day (or at least three times per week) should begin when two teeth touch – usually when the back teeth

appear. Children will need to be assisted by an adult to do this.

Preventing dental caries

Do not give infants sweet drinks before bedtime – water or milk is best. Babies may get dental caries from

sucking for long periods of time on bottles containing sweetened drinks or from sleeping with a bottle in their mouth.

They produce less saliva at night to neutralise the acidic substances which cause decay. Dummies should always be clean,

never shared and never dipped in sweetened substances.7

Use a training cup as soon as the child can drink from one and discontinue the use of a bottle from the age of one

year. Sweet drinks should only be consumed at meals and avoid fizzy drinks until the child is at least 30 months old.3 Discourage

snacking and grazing throughout the day – teeth need a break!

Parents should remember that their own oral health impacts on the oral health of their child. Streptococcus mutans

is a cariogenic bacteria that can be transmitted from the parent to the child via, for example, by pre-tasting food with

the same spoon used to feed, or putting their child’s dummy in their own mouth.

Managing teething pain

Symptoms of teething may include excessive drooling, chewing/mouthing, appetite loss and generally unsettled behaviour.

Parents often report fever, diarrhoea and other systemic symptoms, however there is no evidence that these symptoms are

caused by teething. If a child is systemically unwell they should be assessed for the presence of an underlying medical

condition.1,4

Management is symptomatic and includes self-care measures, and oral analgesia if required.

Chewing can ease discomfort

Self-care measures include gently rubbing the gum with a clean finger and allowing the infant to bite on a clean, cool

object e.g. a teething ring or wet facecloth. Chilled fruit could be used at snack time in infants who have been weaned,

but it should be supervised due to the choking hazard.

Teething rings or other devices should be in one piece to prevent a choking hazard and should not be dipped in sweet

substances as this may result in dental caries over time. Teething biscuits and rusks that contain sugar are not recommended.4

Pharmacological management – little evidence of benefit for topical teething gels

There is little evidence that topical teething gels are effective in reducing the pain and discomfort associated with

teething.1,4 This is partly due to the fact that after application the gel is likely to be rapidly removed

by the tongue and saliva.

In the UK, teething gels containing choline salicylate (e.g. Bonjela, Ora-Sed Gel) are contraindicated in children aged

under 16 years due to the theoretical risk of Reye’s syndrome.4 Bonjela has been reformulated with lignocaine

in some countries, but not in New Zealand. Medsafe is satisfied that the safety of teething gels containing choline salicylate

in children is acceptable when they are used at recommended doses.5

Choline salicylate teething gels should not be used in children aged less than four months and the approved dose is

to apply a small quantity of gel (i.e. tip of index finger) to the affected area no more than every three hours for pain.5

Topical anaesthetics (e.g. containing lignocaine) and complementary therapies such as herbal teething powder are not

recommended as there is no good evidence to support their use. There are also some case reports of serious adverse effects

such as seizures with excessive use of topical anaesthetics.4

Paracetamol or ibuprofen may be considered

Paracetamol or ibuprofen may be used for teething pain in infants aged three months or older. Paracetamol is

preferred in children with asthma or wheeze.4

Best practice tip: Sugar free medications should be used for

children, where available and appropriate. This is especially important with medications that are held in the mouth such

as teething gels.

Best practice tip: Sugar free medications should be used for

children, where available and appropriate. This is especially important with medications that are held in the mouth such

as teething gels.

Teething necklaces pose risk of strangulation or choking

Necklaces made from amber beads have been gaining popularity for use in babies who are teething. It is claimed that

the amber soothes the pain of teething when worn next to the skin.

These necklaces are not recommended as there is no evidence that amber is an effective analgesic and they pose a serious

risk of choking or strangulation. If parents choose to use this device the infant must be supervised at ALL times while

wearing the necklace (including sleeping).8

The truth about drooling

Contrary to appearances, babies do not produce more saliva than the average adult – they just let it escape more easily.

Drooling may increase at times of teething, This is usually due to the fact that the baby is chewing on items to ease

teething pain, therefore more saliva escapes. Most babies cease drooling by 12 to 18 months as they begin to eat more

solid food and their ability to chew and swallow develops adequately.

Babies may also drool more if they have a sore throat and it is painful to swallow. If a parent complains of excessive

drooling in their infant consider this diagnosis.

Lumps, bumps and sores

Gingivitis is common in children

Gingivitis is a reversible inflammation of the gingiva caused by dental plaque build-up due to poor oral hygiene. It

is commonly seen in children and can be exacerbated by malnutrition and viral infections.2

Gingivitis usually resolves after the plaque is removed, therefore improved oral hygiene is the key to management. Regular

supervised tooth brushing with an appropriate sized toothbrush, fluoride toothpaste and the use of dental floss is recommended.

If gingivitis remains untreated, bacterially induced periodontitis may occur. This involves irreversible destruction

of the supporting tissues surrounding the tooth, including the alveolar bone. Chronic periodontitis is more likely to

occur in adolescence rather than in younger children. However on rare occasions young children may have signs of aggressive

periodontitis.2

Children with chronic gingivitis or signs of periodontitis should be referred to a dentist.

For correspondence regarding vitamin D and oral health, see "Correspondence: Vitamin D, oral health and pregnancy", BPJ 29 (July, 2010).

For correspondence regarding vitamin D and oral health, see "Correspondence: Vitamin D, oral health and pregnancy", BPJ 29 (July, 2010).

Oral thrush: treatment choices, preventing re-infection

Oral thrush (candida) is common in infants and young children because their immune system is immature. It occurs in

neonates after exposure to the microorganisms of the vaginal tract during delivery, and in older infants after use of

antibiotics or inhaled corticosteroids.9

Oral thrush is characterised by white plaques on the buccal mucosa, palate, tongue or oropharynx. If the plaques are

wiped off, it leaves a red, raw, painful surface.9

Milk or food debris in an infant’s mouth can often be mistaken for thrush. In contrast to thrush plaques which

are firmly attached, debris sits loosely on the mucosa and does not leave a raw surface when wiped off.

Treat oral thrush with miconazole gel

First-line treatment is with miconazole oral gel (Daktarin Oral Gel) for seven days. Treatment should be continued

two days after symptoms resolve.10 Miconazole gel is contraindicated in children less than six months old

or in those with insufficiently developed swallowing reflex.

If the infection has not resolved after seven days, but there has been some response to miconazole treatment, continue

for further seven days.

If miconazole has not had any effect or is inappropriate (e.g. child less than six months) a second-line alternative

is nystatin suspension (Nilstat Oral drops), 1 mL, four times per day, for seven days.10

Seek specialist advice if the infant has extensive or severe thrush which is causing difficulty swallowing, there has

been no response after two weeks of treatment or the infant has had repeated episodes of thrush.

Application of miconazole gel

Apply directly to affected area after eating (or breast feeding) using the fingertip and leave in contact with

the mucosa as long as possible. Be aware of the risk of choking and avoid application to the back of the throat.10

- 6 months – 2 years : ¼ measuring

spoon* two to four times per day

- >2 years: ½ measuring spoon two to four times per day

Preventing re-infection

To prevent re-infection it is important that feeding equipment, dummies and toys that have been in contact with

the baby’s mouth are sterilised. Also consider that breast feeding mothers may have a yeast infection on their

nipples which requires antifungal treatment. The same product used for the baby may be used on the mother’s nipple.

Best practice tip: In older children, thrush is a common dose related effect

of inhaled corticosteroids. To prevent infection, advise on good inhaler technique, using a spacer to reduce the impact

of particles in the oral cavity, rinsing the mouth with water or cleaning teeth after inhalation to remove any drug particles.

Consider stepping down the dose of ICS where appropriate.10

Best practice tip: In older children, thrush is a common dose related effect

of inhaled corticosteroids. To prevent infection, advise on good inhaler technique, using a spacer to reduce the impact

of particles in the oral cavity, rinsing the mouth with water or cleaning teeth after inhalation to remove any drug particles.

Consider stepping down the dose of ICS where appropriate.10

Angular cheilitis

Angular cheilitis, also known as perleche or angular stomatitis, is an inflammatory condition that occurs in one or

both corners of the mouth. Presentation includes erythema, painful cracking, scaling, bleeding and ulceration. In children

it is particularly associated with drooling, using dummies, licking the lips and sucking the thumb.11

The most common causes are Candida albicans or Staphylococcus aureus. Contact allergy, nutritional

deficiencies (e.g. iron, folate), dry skin, hypersalivation and dermatitis may also play a role.11

Treatment of angular cheilitis is dependent on the cause. A simple first measure is to regularly apply petroleum jelly

to the affected area.

If candida is suspected, an antifungal ointment such as miconazole gel or cream (Daktarin Oral Gel, Multichem Miconazole)

or nystatin cream (Mycostatin cream) may be used. If infection with S. aureus is suspected, topical treatment

with fusidic acid cream (Foban) is recommended.11 Mupirocin ointment (Bactroban) can also be used but as it

is effective against MRSA, it is best reserved for this.

Good oral hygiene measures and regular use of petroleum jelly can help to prevent recurrence.12

Eruption cysts

Eruption cysts are sometimes formed when primary or permanent teeth emerge from the gingiva. They are caused by fluid

accumulation within the follicular space of the erupting tooth. An eruption haematoma is when the fluid is mixed with

blood. Eruption cysts and haematomas do not require treatment as they resolve spontaneously when the tooth breaks through.9

Gum boils

A parulis or “gum boil” is a lesion (soft, reddish papule) that occurs at the site of drainage of a primary

tooth abscess. Treatment of the abscessed tooth usually resolves the parulis. If the tooth is left untreated, the parulis

may mature into a fibroma.9

Ulcers

Traumatic mouth ulcers are the most common type of ulcer in young children. They are caused by mechanical (e.g. thumb

sucking, scratching, lip biting), thermal (foods and beverages that are too hot) or chemical (e.g. toothpaste, mouthwash)

injury to the oral tissues and can occur on the edges of the tongue, buccal mucosa, lips or palate. Generally, a traumatic

ulcer heals within two weeks and requires symptomatic treatment only.9

Aphthous ulcers or “canker sores” are a form of recurrent ulcer that is more common in older children and

adults. They are painful, shallow, round or oval ulcers with a greyish base.9 They usually persist for longer

than a traumatic ulcer and have been associated with vitamin deficiencies, anaemia, food allergies, stress and local trauma,

although a specific trigger is often not found.

Herpes simplex virus

Herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV) manifests approximately one week after contact with an infected person. It may be associated

with flu-like symptoms, often attributed to “teething”. In young children the virus is commonly expressed

as gingivostomatitis, which includes inflamed gingiva, possible bleeding and clusters of small vesicles that become yellow

after rupture and are surrounded by a red halo. Smaller vesicles combine to form large painful ulcers.9

Treatment is supportive to avoid dehydration – encourage fluid intake including ice or popsicles. Analgesics may also

be used. Antiviral treatment such as oral aciclovir is effective only during active viral replication, which precedes

symptoms, therefore it is not usually beneficial. Care must be taken to ensure the virus does not spread to the eyes,

genitalia or fingernail beds. Symptoms of HSV infection usually start to improve within three to five days and lesions

typically fully resolve within two weeks.9

After primary infection, HSV lies latent until reactivated by exposure to sunlight, cold, trauma, stress or immunosuppression.

When it recurs on the lips it is known as herpes labialis (cold sores). These lesions are typically preceded by tingling,

burning or pain at the site. Treatment is with local analgesics. Topical aciclovir is not generally recommended in young

children. Sunscreen containing lip balm may help to prevent recurrence of lip lesions.9

Oral habits - do they need to be corrected?

Non-nutritive sucking is very common in infants

Non-nutritive sucking (e.g. sucking on a dummy or a digit) is a self-soothing behaviour that occurs in most infants.

It is less common by the age of four to five years. Digit sucking is more likely than dummy sucking to persist past this

age.13

Figure 1a: Child sucking thumb

Figure 1b: Open bite caused by thumb sucking in the same child.

Photos kindly supplied by D. Boyd. |

Digit sucking can be associated with malocclusion of the teeth including an open bite, crossbite or excessive overjet

(overbite).13 In most cases parents can just ignore digit sucking in young children, but treatment may be necessary

if physical (Figures 1a and 1b) or psychological factors become apparent. The American Academy of Paediatric Dentistry

recommends that children aged over three years, with a digit sucking habit, should be referred to a dentist for evaluation.

Most orthodontists recommend that the habit is corrected before the permanent incisors erupt (approximately from six years

old).

Some suggested strategies for intervention include:13

- Discontinue comments about digit sucking if parental attention appears to have reinforced the behaviour

- Manage sources of stress and anxiety for the child

- Give positive reinforcement for avoidance of sucking (e.g. sticker chart and praise)

Use of a dummy (pacifier) is associated with an increased risk of development of otitis media14 and early

cessation of breast feeding (also shorter duration of feeds and fewer feeds per day).15 However infants who

use dummies have a possible decreased risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)16 and may be less likely

to suffer malocclusion than those who suck digits. The use of a dummy does not appear to increase the prevalence of caries

unless it has been routinely dipped in a sugary substance.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) discourages use of dummies due to the association with early cessation of breast

feeding. However the American Academy of Paediatrics recommends that dummies be given to infants at nap time and bed time

to reduce the risk of SIDS. It suggests that dummies could be introduced after breast feeding has been established (after

approximately one month) and that they should be withdrawn by the time the child reaches three years.13

Mouth breathing

Chronic mouth breathing can be caused by nasal obstruction or congestion (e.g. from allergies), adenoidal hypertrophy

or anatomical abnormalities (e.g. cleft palate). It may also be a learned habit.13

Chronic mouth breathing can result in narrowing of the maxillary arch (causing a posterior crossbite), over-eruption

of the permanent molars and rotation of the mandible.13 These effects can create the overall appearance of

a long, narrow face. Chronic mouth breathing is also associated with localised gingivitis, usually at the front of the

mouth.2

Treatment of the nasal congestion or obstruction improves mouth-breathing and usually results in improved facial morphology

over time.

Bruxism (teeth grinding)

Bruxism, or teeth grinding, usually occurs during sleep, but it also may be an unconscious day-time habit. Bruxism is

most common between the ages of seven and ten and is rarely seen in adolescence. It does not usually require intervention

in children and is self-limiting.13

Fraenal attachments: issues and management

Maxillary and mandibular fraenum

In infants, the maxillary fraenum (attached to upper lip) extends over the ridge of the alveolar bone and forms a raphe

that connects to the palate. If this raphe persists, it may result in widely spaced central incisors (diastema)(Figure

2).

Figure 2: The large upper labial (maxillary) fraenum is restricting the ability to raise the

upper lip and has caused a diastema in the front teeth.

Photo kindly supplied by D. Boyd. |

Treatment of this condition is usually delayed until the permanent teeth have erupted to allow natural closure of the

diastema. Immediate treatment is necessary if the fraenum causes tension on a permanent tooth. A fraenectomy may be performed

if the appearance of the diastema is unacceptable after natural and orthodontic closure of the diastema.9

The mandibular fraenum (attached to lower lip) less commonly causes a diastema in the bottom front teeth. Management

is the same as for the maxillary fraenum.9

Ankyloglossia (tongue-tie)

Ankyloglossia (tongue-tie) is a congenital anomaly in which a short lingual fraenum (attached under the tongue) restricts

tongue movement.17

Clinical features of ankyloglossia include:17

- Short fraenum, connecting at or near tip of tongue

- Difficulty lifting the tongue to the roof of the mouth

- Inability to protrude the tongue more than 1 – 2 mm past the front teeth

- Impaired sideways movement of the tongue

- Notched or heart shaped tongue when it is protruded

There is a lack of consensus as to the clinical significance of ankyloglossia and whether it requires correction.

The majority of infants with ankyloglossia are able to breast feed successfully. However, of those infants who have

breast feeding problems, more have ankyloglossia than do not.17 If an infant with ankyloglossia is having difficulty

breast feeding, a lactation specialist should be consulted first to discuss techniques which may improve feeding.

It is not clearly defined how ankyloglossia affects speech. It may cause articulation problems in some children (depending

on the severity of the ankyloglossia) but does not prevent speech or delay its onset.17 If there is concern

the child should be referred to a speech therapist.

Mechanical issues of ankyloglossia can include difficulty with oral hygiene (which may result in periodontal disease),

discomfort, a gap between lower front teeth, difficulty licking food or playing a wind instrument.17

Some experts believe that progressive stretching and use of the fraenum over time leads to elongation, and treatment

of ankyloglossia is unnecessary. Others advocate that it should be surgically corrected before problems develop.17 Treatment

decisions should be made between the parents and clinician, on a case by case basis.

Fraenotomy is when the fraenum is incised to release it from the tongue. It may be performed with or without anaesthesia.

Adverse effects can include excessive bleeding, infection, ulceration, pain, damage to the tongue and recurrence. It should

only be performed by an appropriately trained clinician.

Tooth trauma

Approximately half of all children injure their teeth during childhood.18 If the injury is to the primary

dentition, the full extent of the damage cannot be ascertained until the permanent teeth emerge. It is important that

injuries to the teeth in children are treated quickly and appropriately.18

Falls are the most common cause of dental injury among preschool and school-aged children and most falls occur inside

the home. Sports-related injuries and altercations are more common in older children and in boys.18 Orofacial

injury occurs in up to 75% of cases of child abuse and this should be carefully considered in cases of dental trauma.19,20

Children with overjets (overbite) of greater than 4 mm are two to three times more likely to experience dental trauma

(due to the position of their teeth).21

If a child presents with a dental injury, first take a neurological history, as dental injuries are classified as head

trauma. If there are neurological concerns, refer to secondary care and follow-up accordingly. Refer for dental assessment

if any of the following apply:18

- The child has spontaneous pain in tooth/teeth following the injury

- Any of the teeth are tender to touch or pressure of eating

- Any of the teeth are sensitive to hot or cold

- There is a change in the child’s bite or occlusion (the child may be unable to close the teeth together)

- There is injury to the lips, fraenula, tongue, oral mucosa or palate (tooth fragments may become embedded in the soft

tissues and lead to infection and fibrosis)

- There are loose, displaced, fractured or missing teeth

Red flags which may indicate further investigation into intentional orofacial injury:18

- Bruises in various stages of healing

- Torn maxillary fraenum (upper lip) – except in a child learning to walk

- Bruising of the labial sulcus (space between lip and gum) in infants who are not walking

- Bruising of the soft tissues of the cheek or neck (accidental falls are more likely to bruise the forehead or chin)

- Hand marks or pinch marks on the cheeks or ears

- A history which is confused or does not correspond with the observed injuries

Managing injuries to the primary teeth

The main focus of managing an injury to the primary teeth is to provide immediate comfort and support and to prevent

damage to the permanent teeth, which develop in close proximity (Figure 3).

Penetrating injuries or infection can irreversibly damage the permanent tooth. Enamel hypoplasia of the permanent upper

incisors may result from an injury in a child less than four to five years old, because this age is prior to the period

of calcification of the permanent incisor tooth crowns (Figure 4). The path of the developing tooth may also be altered.

Minor blows to the teeth can devitalise the dental pulp or damage the periodontal ligament of the permanent tooth. This

may be suggested by discolouration of the crown or an abscess.18

Avulsed primary teeth should not be re-implanted because of potential injury to the developing tooth bud. Examine the

avulsed tooth to ensure that the entire crown and root are present. An x-ray may be required if there is concern that

an avulsed tooth may have been swallowed or aspirated.18 Tooth fragments can also be embedded in soft tissues.

A severely displaced or loose primary tooth can be removed if there is concern that it may be aspirated. The early loss

of primary teeth does not irreversibly affect speech18 however it may affect the position of permanent teeth.

Prompt dental care is required for a fractured primary tooth to prevent further injury or infection.18

Best practice tip: Penetrative injuries. When children present with dental trauma, don’t forget

to check whether there was anything in their mouth at the time of the fall or injury. Consider the possibility of lacerations

to the soft palate or other soft tissues.

Managing injuries to the permanent teeth

Any injury to a permanent tooth requires urgent dental assessment. In the permanent dentition, dental fractures are

more common than displacement injuries (Figure 5). Tooth fragments can sometimes be reattached. They can be stored in

tap water (as there is no root or ligament) to prevent dehydration.18

An avulsed permanent tooth should be placed back in the socket, taking care to handle the tooth by the crown and not

the roots. The tooth may be kept in place with a finger or biting on a gauze pad. Before re-implanting, debris can be

removed from the tooth by gentle rinsing with saline. Do not sterilise or scrub the tooth. The prognosis for the survival

of an avulsed tooth is inversely related to the time spent outside the mouth (85 – 97% at five minutes to almost 0% at

one hour).18

If it is not possible to re-implant the tooth, it should be stored in fresh, cold milk or in saline. Do not store the

tooth in tap water or in a young child’s mouth as it could be swallowed, aspirated or further damaged.18

Displaced or loose permanent teeth should not be moved or pulled out. Refer immediately to a dentist who may treat the

tooth using a splint.18

Properly fitted mouth guards reduce dental injury

Mouth guards are compulsory in New Zealand for children playing rugby, rugby league and hockey but their use should

be encouraged for all contact sports.

Custom-made mouth guards provide the most protection but are also the most expensive. Self-adapted mouth guards (boil

and bite) are an acceptable cost-effective alternative.

In addition to decreasing the risk of dental trauma, properly fitted mouth guards can reduce the incidence of concussion

and jaw fracture by cushioning the force of the impact.22