Clinicians who want to encourage people to quit smoking are likely to be more successful if they have some understanding

and empathy for why people start smoking and continue to smoke. This understanding and empathy is unlikely to come from

experience as statistics show only 3.4% of New Zealand medical practitioners are regular smokers and 81.4 % have never

smoked.1

In this article we look at what are commonly perceived by smokers as the “benefits” of smoking, along with some of the

more significant barriers to quitting.

Why do people start smoking?

It has been estimated that 80% of adult smokers begin smoking as children, and about 30% of children have tried smoking

by the age of 11.2

There is no single reason why young people begin to smoke.

Predisposing factors such low socioeconomic status, adverse childhood experiences and mental illness are generally not

easily changed. Knowing about these factors is useful because they can help identify which young people might be at greatest

risk for smoking and in greatest need of support to resist smoking.

Influencing factors provide the opportunity for young people to experiment with smoking. Friends and the presence of

people around them who smoke are major influencing factors. Understanding these influencing factors is useful as many

of them are able to be changed.3

It is important to ensure young people avoid starting to smoke in the first place as nicotine addiction can occur rapidly.

In one study, 10% of children who became regular smokers showed signs of nicotine dependence within two days of first

inhaling from a cigarette, and 25% within a month.4 Within a year of starting to smoke, it has been reported

that children will be inhaling the same amount of nicotine as adults, will experience cravings when they do not smoke,

will make quit attempts and will suffer withdrawal symptoms.5

Why do people continue to smoke?

Because of the effects of nicotine

The primary reason why people smoke is that they are nicotine dependent.

When inhaled, nicotine reaches the brain in 10 to 16 seconds (faster than if it was delivered intravenously), and has

a terminal half life of about two hours. Given this short half life, regular cigarettes are required to maintain nicotine

levels and avoid symptoms of withdrawal.

Nicotine activates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the midbrain, inducing the release of dopamine and exerting

dependence producing effects, in a similar way to amphetamines and cocaine. Nicotine demonstrates a biphasic effect, meaning

it can both invigorate and relax a smoker, depending on how often they smoke. In new users, nicotine improves reaction

time and sustained performance, but tolerance soon develops and these effects are not seen in chronic users.

Nicotine withdrawal has significant physical and psychological effects starting within hours of the last cigarette and

peaking within the first week.

| Table 1: Symptoms of nicotine withdrawal5 |

| Symptom |

Duration |

Incidence (%) |

| Lightheadedness |

<48 hours |

10 |

| Sleep disturbance |

<1 week |

25 |

| Poor concentration |

<2 weeks |

60 |

| Craving for nicotine |

<2 weeks |

70 |

| Irritability or aggression |

<4 weeks |

50 |

| Depression |

<4 weeks |

60 |

| Restlessness |

< 4 weeks |

60 |

| Increased appetite |

< 10 weeks |

70 |

Because of the behavioural rewards

Continued smoking is also influenced by non-nicotine effects, including the sensory-motor effects of smoking as well

as smoking-associated behaviours that become reinforced.

A person smoking a pack of cigarettes a day can accrue over 70 000 deliveries of nicotine per year. The sight, smell

and sensations of smoking have a behavioural conditioning effect on the brain. While nicotine replacement therapy can

be very successful in achieving smoking cessation, it does not address the non-nicotine effects of smoking.

Smoking has been shown to elicit a strong Pavlovian response for many people. For example, having a cup of coffee, concluding

a meal, seeing another person smoke or smelling smoke may trigger the psychological desire to smoke. The Pavlovian response

is considered a reason a number of light smokers, with low nicotine dependence, continue to smoke.6

Social norms play a role in continued smoking. In some cases this will discourage smoking, e.g. the increasing number

of smoke free public areas and work places and the increasing number of smoke free messages. On the other hand, in groups

where the smoking prevalence is high, this may constitute the social norm; therefore there may be less of an expectation

to quit.

Because cigarettes help people deal with stress

Many people think they need cigarettes to help them relax and cope with stressful situations. Many smokers report they

feel calmer and have improved concentration after a cigarette. However, it is more likely that declining nicotine levels

begin to cause symptoms of withdrawal including agitation, and smoking another cigarette simply restores nicotine levels

alleviating these effects.

It is also worth considering the actions associated with smoking. For example people may go outside to smoke, removing

themselves from the stressful environment and creating an opportunity to “clear their head”. Furthermore, the smoke is

often inhaled and exhaled in a slow and often deliberate manner – similar to relaxation breathing techniques. Each of

these are useful methods in their own right for dealing with stress, so it may be useful to remind people they already

have the skills to manage stress, even if they don’t realise it.

Because of concern of weight gain on stopping

Many people, especially young women, believe that smoking helps them to maintain a lower body weight. Following smoking

cessation, weight gain occurs in approximately 75% of people,7 with an average gain of around 7 kg.8

It is thought some of this weight gained is caused by a decrease in metabolic rate following smoking cessation. In some

people the metabolic rate may slow down even further and return to normal over a period of weeks or months.

The lifetime benefits of quitting

Many of the major risks associated with smoking decrease within two to five years of quitting smoking. For some conditions

a residual risk remains and never returns to the level of a non-smoker. This is summarised in Table 2.

Following smoking cessation, many people have an increased appetite, which may last for two to three months.

There are also several behavioural aspects that may influence weight gain. Ex-smokers may miss the familiar mouth and

hand actions of smoking and replace this with snacking. People that smoke to deal with stress, boredom or loneliness may

replace their smoking rituals with increased food intake.

While smokers should be aware they may gain weight when they stop smoking, it is not inevitable. It is important to

incorporate advice on a healthy diet and exercise into a quit-plan. However a recent Cochrane Review concluded that advice

alone on healthy lifestyles is not effective and may reduce abstinence. More focused intervention is required.8

| Table 2: Modification of risk upon quitting smoking (adapted from Dresler et al 2006)9 |

| Disease |

Risk lower in former smokers than continuing smokers |

Time for risk reduction |

Returning to level of non-smoker |

| Lung cancer |

|

5–9 years |

Never |

| Laryngeal cancer |

|

60% after 10–15 years after cessation |

Not for at least 20 years |

| Oral and pharyngeal cancer |

|

Inadequate data |

20 years |

| Stomach cancer |

|

Decreases with continued abstinence, lower risk associated with younger age at cessation |

Inadequate data |

| Pancreatic, renal cell, and bladder cancer |

|

Decreases with continued abstinence |

Pancreatic – 15 years

Renal cell – 20 years

Bladder cancer – 25 years |

| Coronary heart disease |

|

35% in 2–4 years |

Variable: 10–15 years, others small risk after 10–20 years |

| Cerebrovascular diseases |

|

Marked reduction in 2–5 years |

Variable: some say 5–10 years, other say residual risk after 15 years |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm |

|

Inadequate data |

Residual risk may always remain higher |

| Peripheral arterial disease |

|

Inadequate data |

Residual risk may always remain higher |

| COPD |

|

Improvement in FEV1 during first year |

After 5 years, the age related decline in FEV of ex-smokers reverts to that of never-smokers |

| Chronic bronchitis |

|

Symptoms reduce rapidly within a few months |

Prevalence of symptoms are same as never-smokers within 5 years |

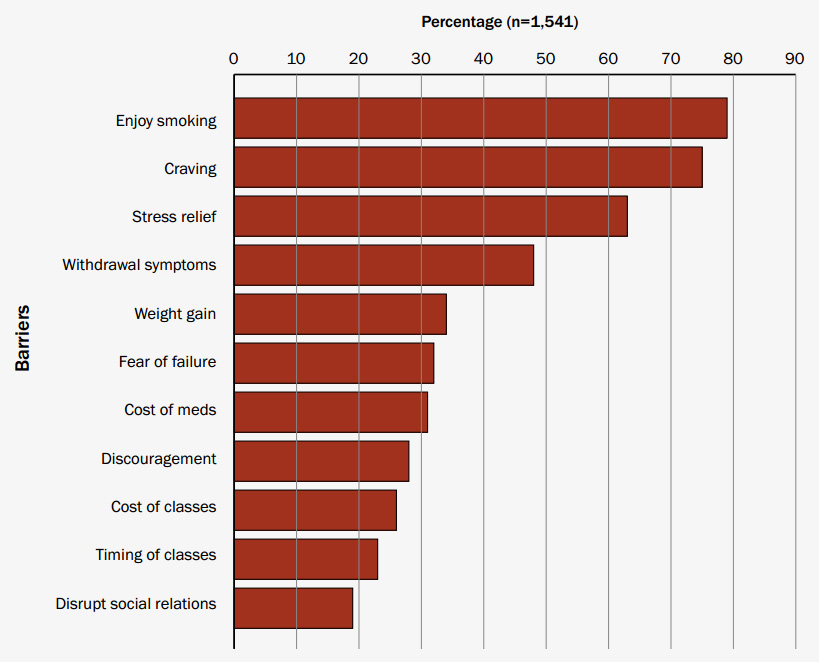

Barriers to quitting

There are a number of barriers that make it difficult for people to stop smoking. These barriers vary depending on age,

gender and number of cigarettes consumed.

In a survey of 1500 smokers, over 80% wanted to quit, but factors such as enjoyment, craving and stress relief reduced

their desire to attempt quitting (Figure 1).7

Figure 1: Barriers to quitting smoking (adapted from UW Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention,

2005)7

People who live with other smokers find it more difficult to quit and this is associated with a higher incidence of

relapse.