In this article

View /

Download pdf version of this article

Practical tips and information for routine laboratory testing during pregnancy

When a woman becomes pregnant, it is recommended that she receives a range of standard laboratory investigations. “A

first antenatal screen” is required even if the woman is considering termination of pregnancy. Women who do not receive

any antenatal testing are at risk of poorer antenatal and perinatal outcomes. It is also likely that these women receive

fewer than the recommended antenatal visits.1,2

Approximately 50% of women do not book with a Lead Maternity Carer (LMC) until the end of the first trimester, meaning

the “first antenatal screen” is often the responsibility of the general practitioner at the first appointment when pregnancy

is confirmed and the results later forwarded to the chosen LMC. In 2013, 77% of all first antenatal screens were requested

by doctors. Clinicians who are not the LMC may access funding for one pregnancy-related visit during the first trimester.

Prior to all laboratory testing in pregnancy, information should be provided to the pregnant woman about why the test

is recommended, the risk of disease transmission to the foetus (if relevant), how the results will be delivered and the

implications of both positive or negative results.3

Pregnant women in New Zealand

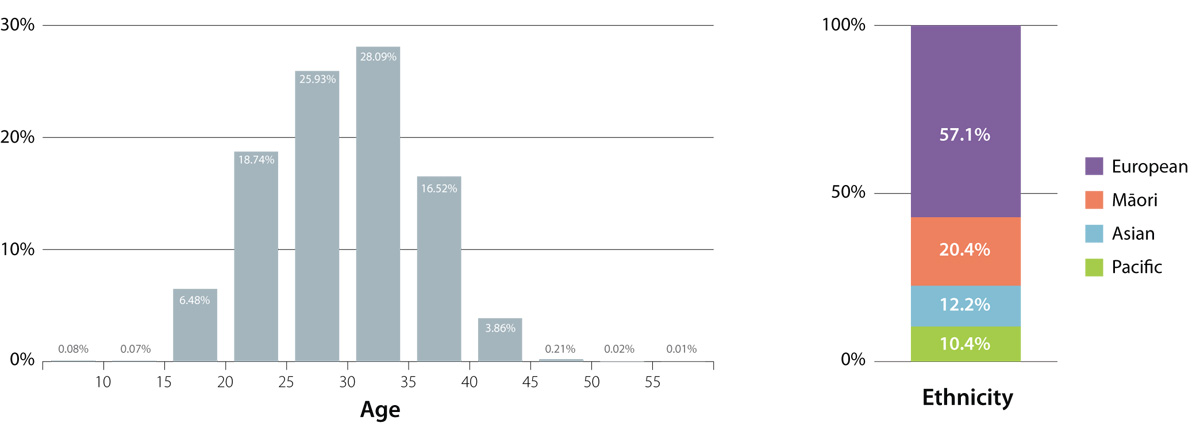

In 2013, 53,309 women who were registered with a general practice were admitted to a New Zealand hospital for maternity

services (for delivery of a baby). The figures below show the age and ethnic breakdown of these women.

Testing Rates

The intended outcomes of antenatal tests are to provide baseline results and minimise harm to the mother or foetus during

the remainder of the pregnancy (e.g. gestational diabetes, HIV).4

Of the 53,309 women who were admitted to maternity services*

- 87% had a first antenatal screen

- 84% had a second antenatal screen

- 5.5% had no screening

Women aged < 20 years or ≥ 45 years and women of Māori ethnicity are the

most likely groups to receive NO ANTENATAL TESTING.

1st antenatal screen |

2nd antenatal screen |

Although the first antenatal screen usually occurs early in pregnancy, it may be requested at any

stage of pregnancy. Tests included in the first antenatal screen include:

- Complete blood count

- Blood group and antibody screen

- Rubella antibody status

- Syphilis serology

- Hepatitis B serology

- HIV

|

Usually completed at 26–28 weeks gestation. The second antenatal screen includes:

- 50 g glucose tolerance test (the ”polycose” test)

- CBC

- Blood group antibodies

|

See Best Tests July 2011 for more information on

routine laboratory testing during pregnancy

See Best Tests July 2011 for more information on

routine laboratory testing during pregnancy

Sample Practice Data

Sample Practice Name had 27 women admitted to maternity services during 2013. Due to inaccuracies in the laboratory

database we are unable to provide you with your practice level testing rates, however the table below shows the ethnic

and age breakdown of the women registered to your practice and admitted to maternity services in 2013. The highlighted

rows are those women most at risk of receiving NO ANTENATAL TESTING.

| Age |

Number of women

(% of total) |

| 10 to 14 |

0 (0%) |

| 15 to 19 |

2 (7%) |

| 20 to 24 |

9 (33%) |

| 25 to 29 |

8 (30%) |

| 30 to 34 |

6 (22%) |

| 35 to 39 |

2 (7%) |

| 40 to 44 |

0 (0%) |

| 45 to 49 |

0 (0%) |

| 50 to 54 |

0 (0%) |

|

| Ethnicity |

Number of women

(% of total) |

| Asian |

1 (4%) |

| Māori |

9 (33%) |

| Pacific |

1 (4%) |

| European/Other |

16 (59%) |

|

*These results are based on the cumulative results from DHBs where the recording of antenatal screening is most accurate

(Southern, Auckland, Counties Manukau, Waitemata and Hawke’s Bay). Patients from these five DHBs account for 49% (n=26,238)

of all women who were admitted to maternity services in 2013.

- Arroll N, Sadler L, Stone P, Masson V, Farquhar C. The New Zealand Medical Journal 2013;126:46-56

- Stacey T, Thompson J, Mitchell E, Zuccollo J, Ekeroma A, McCowan L. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics

and Gynaecology 2012;52:242-247

- National Screening Unit. Guidelines for maternity providers offering HIV screening in New Zealand. Wellington: National

Screening Unit, 2008.

- Harris M, Franck L, Michie S. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 2012;30:222-246