Crying and irritability: a normal part of infancy or a pathological cause?

The phrase “sleeping like a baby” is intended to mean peaceful sleep, however, the reality is that babies

frequently wake, cry and require feeding. Although much variation occurs, crying generally increases at age two weeks

before peaking at age six to eight weeks while a diurnal sleep/wake cycle is established.1 Some infants will

display excessive crying and irritability which may cause parental anxiety � particularly for first time parents. Sometimes

parents suspect a pathological reason for their infant’s distress with up to 20% of parents reporting a problem

with infant crying or irritability in the first three months of parenthood.2 However, in most cases, no medical

intervention is required.

Gastric reflux

“Reflux” is commonly blamed for infant irritability, however, this is a normal occurrence in an infant and

generally does not require medical treatment. Parents can be provided with reassurance and practical advice for managing

the symptoms (below).

An infant’s body weight roughly triples in their first year of life and their caloric intake is high. Due to the

frequency and relative size of an infant’s feeds, their stomach is often distended and may require relief through

transient oesophageal sphincter relaxations � otherwise known as gastric reflux.3

Uncomplicated reflux is a normal process involving the involuntary passage of gastric contents into the oesophagus.

This occurs asymptomatically throughout the day, and may involve movement of food, drink and saliva, as well as gastric,

pancreatic and biliary secretions. Reflux is less acidic in infants than in older children and adults, as the stomach

contents are buffered by the frequent consumption of milk.

Regurgitation

Regurgitation is the appearance of refluxed material in the mouth. Approximately 40% of infants regurgitate at least

once a day.4 In most cases, regurgitation resolves over time without treatment.

Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease (GORD)

Infantile GORD is defined as; symptoms or complications of reflux (non-erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux and erosive

oesophagitis) which may include frequent vomiting and regurgitation, poor weight gain, difficulty swallowing, abdominal

or substernal pain, oesophagitis and respiratory disorders.5 GORD is distinct from, and much rarer than normal

infant reflux, however, the similarities between the two can lead to confusion. Frequent regurgitation (more than five

times a day) and persistent feeding difficulties are the most specific clinical indicators of GORD.6 Persistent

crying is not a reliable indicator of GORD. One study found that only approximately one-sixth of infants presenting with

persistent crying had GORD. Furthermore, the severity of irritability did not correlate with the severity of GORD. Cases

of persistent crying and GORD, in the absence of frequent regurgitation and feeding difficulties were uncommon.6

The initial diagnosis of GORD is based on symptoms and the treatment is frequently empiric, due to a lack of diagnostic

tools and inability to communicate directly with the patient.7 The advantage of this approach is that the need

for invasive procedures is avoided, however, using symptom severity as the diagnostic criterion for GORD can result in

a significant number of cases of uncomplicated reflux being diagnosed as GORD and receiving unnecessary treatment.8

Investigations for infant GORD

If an infant is referred to secondary care for investigation of possible GORD, the following tests may be used:

Barium swallow: This procedure excludes structural abnormalities such as hiatus hernia, oesophageal atresia, tracheosophageal

fistula and malrotation of the upper GI tract. Through imaging the oesophagus, it is possible to observe reflux and in

some cases confirm or exclude oesophagitis or dysmotility. The limitation of this technique is that imaging is only possible

for approximately five minutes therefore episodes of reflux may be missed.

pH monitoring: Performed over 24 hours, this technique is more reliable than a barium swallow at detecting reflux and

is used when:

- Frequent reflux is suspected without regurgitation

- Apnoea is suspected to relate to undetected reflux

- Unexplained respiratory symptoms are thought to be related to undetected reflux

- Before or after surgery to correct reflux

Endoscopy and oesophageal biopsy: Used infrequently, these procedures are useful for diagnosing

oesophagitis, but cannot detect mild reflux. They are considered when there is pain and irritability associated with

an uncertain diagnosis, a poor response to treatment or GI blood loss.

Suggested management plan for irritable, crying infants

Excessive crying and uncomplicated reflux are both common conditions in infants, therefore they often occur simultaneously,

without necessarily being related. Primary care practitioners play an important role in providing parental reassurance

and advice. In most cases, irritability and uncomplicated reflux resolve by age one year.6,9 Infants without

complications of reflux, who are otherwise well and thriving, do not usually require further investigation and treatment.10

Simple advice and reassurance may include the following points:

- Crying generally increases at age two weeks, peaking at around six to eight weeks. As infants age, they generally

cry less and sleep for longer periods at night1

- Reflux and regurgitation are normal because infants ingest large quantities relative to their stomach size, symptoms

usually improve as the infant grows and the digestive system matures

- “Winding” the infant several times during feeds and holding upright after feeds for a short period can

improve symptoms � the parent can place the infant over their shoulder or hold the infant upright on the knee

- Placing the baby on their side decreases reflux, however, this is only appropriate when the baby is awake and closely

observed, due to the risk of sudden infant death syndrome11

- Mothers should be encouraged to persevere with breast feeding

- Feed thickeners (e.g. rice cereal, carob-bean gum, carob-seed flour or carmellose sodium) can be added to expressed

milk to reduce vomiting. Thickened formula is also commercially available, although breast feeding is always preferable.

The evidence of the effectiveness of either of these treatments is limited.11

- Tobacco smoke should be avoided

- Medicines are not recommended

A primary care based study found that two weeks of conservative treatment (feeding modifications, positioning and avoidance

of tobacco smoke) improved symptoms in 78% of infants with frequent regurgitation and irritability and symptoms completely

resolved in 24% of infants during the study period.12

When to refer

Referral to a paediatrician (or paediatric gastroenterologist where available) for diagnostic investigations is indicated

when an infant has excessive reflux and:10

- A failure of conservative treatment (such as feeding advice). N.B. PPIs and H2-receptor antagonists should not be

diagnostically trialled in primary care

- Failure to thrive (see below)

- Suspected oesophagitis due to blood stained vomit, respiratory complications or abnormal posturing or movements

- Diagnostic uncertainty

- Extreme parental anxiety

Failure to thrive is an inability to gain weight in comparison to height. The infant may continue to

grow but with reduced weight gain secondary to reduced caloric intake. Poor weight gain requires evaluation of caloric

intake and ability to swallow. Failure to thrive is associated with multiple underlying conditions, including GORD.

Cows’ milk allergy?

Cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) is an immunologically mediated adverse reaction to cow’s milk protein.

The reaction can be IgE or non-IgE mediated and occurs in approximately 2% of infants aged under two years. It is estimated

that CMPA is the underlying cause in up to 40% of infants referred for specialist management of GORD.13

CMPA is a cluster of syndromes which may include:14

- Immediate allergic reaction, anaphylaxis and food protein-induced enterocolitis

- Gastrointestinal syndromes such as CMPA induced GORD, constipation, enteropathy and allergic eosinophilic gastroenteritis

- Food protein-induced proctocolitis

- Eosinophilic oesophagitis

As many of these syndromes have overlapping symptoms, diagnosis can be difficult. However, eczema and a family history

of atopy increase the risk of CMPA. Complete elimination of cow’s milk from the diet (or the mothers diet if breast

feeding) for two to three weeks and observing if symptoms resolve will usually confirm suspected cases.

For further information see: “Allergy

to cow’s milk protein and the appropriate use of infant formula”, Prescription Foods (May, 2011).

For further information see: “Allergy

to cow’s milk protein and the appropriate use of infant formula”, Prescription Foods (May, 2011).

Omeprazole is not a recommended treatment for reflux or uncomplicated GORD in infants

Omeprazole is a common treatment for gastric reflux in adults, but it is not approved for use in infants aged under

one year. The safety, pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of omeprazole in young children is largely unknown.

Although omeprazole is effective at reducing gastric acidity and oesophageal acid exposure in infants, there is significant

evidence that it is not effective in treating symptoms attributed to infant reflux or GORD. Two studies investigating

the effects of omeprazole on infant irritability and reflux found that, while treatment groups had significantly reduced

oesophageal acid exposure, there was no difference in irritability or crying.15,16 Similar results have been

reported with other proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Of 162 infants aged one to twelve months, there was no difference in

the efficacy of lansoprazole or placebo, in alleviating symptoms attributed to GORD, including; crying, regurgitation,

feeding difficulties, back arching, coughing and wheezing.7

Omeprazole is therefore not recommended for treating irritability, reflux or uncomplicated GORD. Omeprazole should only

be considered in cases of severe infantile reflux oesophagitis or if GORD is causing complications such as failure to

thrive. The decision to prescribe would usually be made in consultation with a paediatrician or gastroenterologist. Even

in these circumstances, the administration of a PPI is unlikely to reduce the frequency of crying and gastric reflux.17

How is omeprazole given to infants when required?

In most cases, initiation of omeprazole treatment in infants should occur in secondary care with pharmacist and paediatric

advice on the most appropriate delivery method. An appropriate dose of omeprazole for an infant is: 5 mg once daily for

children weighing under 10 kg and 10 mg once daily for children weighing between 10 and 20 kg.10

Omeprazole suspension is extemporaneously compounded by mixing capsule contents into sodium bicarbonate solution (8.4%)

and water, normally to a concentration of 2 mg/mL. The suspension should be stored in the refrigerator and discarded after

15 days.18 There is some evidence to suggest that absorption of this formulation of omeprazole is incomplete.20 In

addition, infants often find the taste of this suspension unpleasant.19

An alternative preparation for infants involves sprinkling half the contents of a 10 mg capsule on a small quantity

of apple or pear puree.20 However, it is difficult to achieve an accurate dose with this method and care needs

to be taken that the infant is able to swallow the mixture safely.

Omeprazole capsules and tablets should not be chewed, or dissolved in milk or carbonated water, as this can degrade

the enteric coating.

Adverse effects of PPI treatment

PPIs are generally well tolerated in adults. Uncommon adverse effects include acute interstitial nephritis, hypomagnaesaemia

and hypocalcaemia.21 Little is known about the adverse effects of using PPIs in infants. The most commonly

reported adverse effects of PPIs in children are headaches, nausea diarrhoea and skin rash.22,23

Gastric acid plays an important role in both defending the body from foreign microflora and in regulating gastrointestinal

microflora composition. Reducing acid secretion increases the likelihood of foreign microflora proliferation. A study

of 186 children aged between four and 36 months, found that gastric acid inhibitors were associated with an increased

risk of gastroenteritis and community acquired pneumonia, which persisted for at least two months following treatment.24 Serious

adverse effects, in particular lower respiratory tract infections, were also more frequent in infants symptomatic for

GORD who were treated with lansoprazole compared to placebo controls.7

There are also suggestions that PPI use can cause rebound acid secretion resulting in PPI dependency. A study of 120

adults with no history of acid related symptoms, found that more than 40% of subjects developed such symptoms following

an eight week course of PPI treatment.25 It is unknown if such an effect also occurs in infants.

It has also been speculated that PPI mediated reductions in gastric acidity and digestion, may increase the permeability

of gastric mucosa to some food allergens, potentially increasing the risk of food allergy and eosinophilic esophagitis.26

The absence of long-term data concerning the safety of PPIs in treating infants, combined with reports of serious adverse

effects, regardless of frequency, suggests that PPIs should only be prescribed to infants when the benefit outweighs any

potential risks.

How much omeprazole is being prescribed to infants in New Zealand?

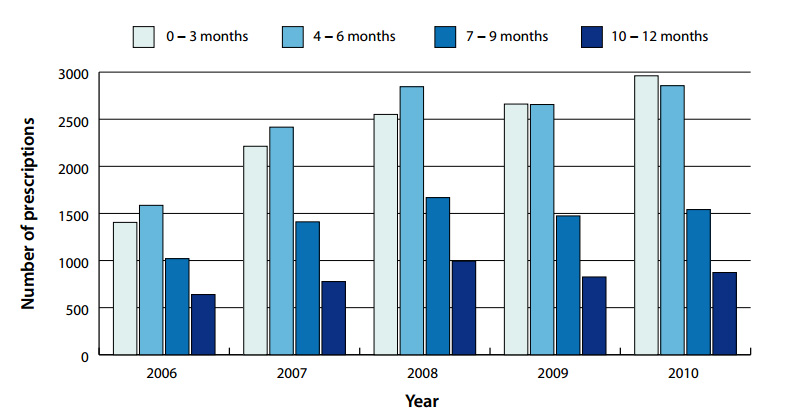

Between 2006 and 2010, the number of prescriptions of omeprazole dispensed for infants aged under one year in New Zealand

increased from 4650 to 8231. The largest increases occurred in the age zero to three months (111%) and four to six months

(80%) cohorts.

This increase is despite a lack of evidence to support the prescribing of omeprazole to infants for symptoms such as

irritability and regurgitation associated with uncomplicated reflux. Omeprazole should only be considered in cases of

severe infantile reflux oesophagitis or in cases of GORD accompanied with failure to thrive.

Figure 1: Number of omeprazole prescriptions dispensed in New Zealand from 2006 to 2010

for infants aged zero to three, four to six, seven to nine and ten to 12 months

Alternative pharmacological options for reflux and GORD in infants

Alginates such as a mixture of sodium alginate and magnesium alginate (Gaviscon infant) reduce acidity and reflux through

increasing the viscosity of gastric contents. They can be used to relieve symptoms of regurgitation or reflux in infants.

Alginates should not be used in infants at risk of dehydration (e.g. acute vomiting or diarrhoea) or intestinal blockage

due to reports of constipation. Gaviscon infant powder is available in sachets. For infants weighing < 4.5 kg, use one

sachet mixed into each feed, and two sachets for infants weighing > 4.5 kg.10 Infants should not be given this medicine

more than six times in a 24 hour period. Unlike adult versions of the medicine, Gaviscon infant does not contain bicarbonate

frothing agents or aluminium hydroxide.

Histamine receptor antagonists such as ranitidine reduce histamine induced gastric acid and pepsin release. Ranitidine

has been shown to be effective in the treatment of some cases of oesophagitis in children,27 and is associated

with a low incidence of adverse effects. However, as with omeprazole, there is no evidence to support empiric treatment

of infants with symptoms of irritability and reflux. In New Zealand, ranitidine is not registered for use in children

aged under eight years and discussion with a paediatrician is recommended before prescribing this medicine to an infant.

Ranitidine is available in a syrup formulation that can be administered to infants at a dose of 2 to 4 mg/kg, two times

daily.10 N.B. ranitidine syrup contains 7.5% w/v ethanol.

Antacids such as magnesium hydroxide and aluminium hydroxide reduce gastric pH, but cases of elevated plasma aluminium

levels in infants combined with a lack of data to confirm efficacy means that these medicines are not recommended for

use in infants.28

Prokinetics such as metoclopramide and domperidone are not recommended for use in infants and there is little evidence

of their effectiveness in the management of GORD.26

Acknowledgement

Thank you to Associate Professor David Reith, Paediatrics & Child Health, Dunedin School of Medicine,

University of Otago, Dr Chris Leathart, General Practitioner, Christchurch and Dr Anna Alderton,

General Practitioner and Clinical Facilitator, Pegasus Health for expert guidance in developing this article.