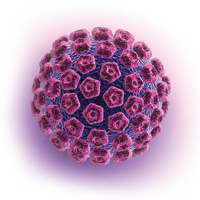

Plantar warts are caused by cutaneous infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV). There are numerous types of HPV

which manifest in different ways. Plantar warts are generally caused by HPV-1, 4, 27 and 57 (see: “HPV vaccine”).1

There is limited high-quality epidemiological data on the prevalence of plantar warts. However, they generally

occur with the greatest frequency in children and adolescents.1 Although plantar warts are not usually associated with

serious clinical consequences, they can cause stress or embarrassment, which should not be underestimated. Plantar warts

are also often painful when present on weight-bearing areas of the foot or when they rub against footwear. Plantar warts

are almost always benign, however, in rare cases (and particularly in people who are immunosupressed), warts of prolonged

duration have been reported to undergo malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma or plantar verrucous carcinoma.2,

3, 4

Diagnosis is based on clinical appearance

Plantar warts can be confused with corns or calluses. The use of a hand-held dermatoscope can assist in diagnosis for

practitioners trained in its use. Warts are characterised by hyperkeratosis or thickening of the skin, and are often found

on pressure points. Small dots or lines are usually visible inside the lesion, which represent broken capillaries and

can range from red to brown in colour.5 They are more clearly shown by dermatoscopy, where red/purple dots or clods (blood

vessels) are surrounded by white circles or lobules (keratin). The blood vessels may become more obvious if the outer

layers of hyperkeratotic tissue are trimmed off. In contrast, corns exhibit a translucent core (concentric fine white

rings on dermatoscopy), while calluses show a generalised opacity across the lesion (structureless on dermatoscopy).5

Multiple adjacent verrucae may form mosaic warts.

Although rare, the most important differential diagnosis in a patient with a suspected plantar wart is melanoma. Other

tumours may also rarely occur in this site (see: “Melanoma of the foot”).

Prevention of transmission

HPV is transmitted by skin contact or contact with surfaces touched by other people with the virus. HPV can be present

for weeks or years before the appearance of a wart, and persists for life, even after the wart has resolved. This may

lead to recurrence at the same site, e.g. if a person who is carrying the virus becomes immunosuppressed; plantar warts

are very prevalent in organ transplant recipients.

People with plantar warts can auto-inoculate HPV and spread infection to other parts of the body. For example, picking

at warts with fingernails may result in transference of infection to the hands. Abrasive implements used to remove thickened

wart skin, and clinical implements such as dermatoscopes, have been shown to retain detectable HPV DNA.6, 7 Whether this

contamination represents transmissible virus is uncertain, but as a precautionary measure any implements used on the wart

should be sterilised or discarded after use.

Children frequently acquire warts from infected family members or in a classroom environment, therefore, prevention

efforts need to focus on the both the home and school.8, 9 Going barefoot in public spaces, around swimming pools or in

shared bathroom areas increases a person’s risk of HPV infection. People already infected with plantar warts should be

advised to take precautions to reduce transmission to others, such as wearing footwear in the home and school environments

and covering warts with tape before using communal areas.

Treatment of plantar warts

Up to 80% of people will experience resolution of plantar warts without intervention within two years.10 Many patients

will, however, wish to attempt treatment. All topical treatments for warts have variable success rates, therefore several

different management methods may need to be trialled before the wart is resolved. Wart paints and gels containing salicylic

acid show good evidence of efficacy, and can be recommended as a starting point for patients who wish to trial a treatment.

Watch and wait

It is estimated that cure rates of plantar warts with a watch and wait approach are likely to be in the range of 25%

over a period of a few months.11 Eventually, most warts will resolve without treatment, but this may take several years.

If the wart is causing discomfort, the wart surface can be abraded with an emery board (disposable nail file), pumice

stone or a similarly abrasive surface. Patients should be advised that items used on the wart should be discarded after

use or sterilised (e.g. placed in boiling water for five minutes or soaked in bleach) to reduce the risk of viral transmission.

The lesion can also be debulked to improve absorption of creams or ointments into the underlying infected tissue, if pharmacological

treatment is trialled.

Topical creams and ointments

Most topical treatments for plantar warts are recommended as a daily application until the wart has resolved. There

are no specific guidelines for when treatment efficacy should be reviewed or when to switch to an alternative treatment.

Salicylic acid

Topical treatment with salicylic acid is often regarded as a first-line approach to treating plantar warts. Salicylic

acid is a keratolytic agent and works by debriding the skin. Salicylic acid 27% gel (general sale) should be carefully

applied to the wart, once daily. The surrounding skin should be protected, e.g. with soft paraffin or a specially designed

plaster. The wart should be gently abraded with an emery board or pumice stone once a week. Treatment may need to be continued

for up to three months.12 A Cochrane systematic review of the treatment of warts included two studies assessing the efficacy

of salicylic acid for plantar warts, and found a 29% increase in cure rate with salicylic acid over placebo after 12 to

13 weeks.13

Topical salicylic acid may cause irritation if applied to fissures or abrasions. Caution is recommended in patients

with reduced skin sensation (e.g. patients with diabetes) as over-application may cause skin ulceration.12

Silver nitrate

Silver nitrate (general sale) is available in the form of a stick which is moistened (ideally with distilled water rather

than tap water) and applied directly to the wart for one to two minutes.14 Treatment should be applied once daily for

a maximum of six applications.14 The surrounding skin should be protected. The efficacy of silver nitrate treatment has

only been assessed in one randomised controlled trial where patients using silver nitrate showed complete cure rates approximately

30% higher than patients using placebo applications.13 Adverse effects include stains on surrounding skin, or clothing

coming into contact with the application area, as well as the possibility of chemical burns.12

Fluorouracil (5-FU)

Fluorouracil is a chemotherapeutic agent used in the treatment of various cancers. Topical fluorouracil is indicated

for malignant and pre-malignant skin lesions. The use of fluorouracil cream for plantar warts is an off-label indication.

After debridement with a pumice stone, patients can be instructed to apply fluorouracil 5% cream (prescription only, subsidised)

to the lesion, twice daily.15 The wart should be covered with an occlusive dressing after each application of fluorouracil

with treatment continued for up to 12 weeks.15 Complete eradication rates as high as 95% have been reported after 12 weeks

of treatment with fluorouracil 5% cream.15 Patients may experience pain, blistering and local irritation. When used close

to the nail, fluorouracil can cause nail detachment.13

Other treatments for plantar warts have limited evidence of effectiveness

Imiquimod and podophyllotoxin

These two medicines are not indicated for the treatment of cutaneous warts. While they should theoretically be useful

given their indication for the treatment of anogenital warts, there is little evidence at present to support their use

for plantar warts.

Imiquimod 5% cream has been assessed in two randomised controlled trials for the treatment of cutaneous warts, conducted

by the manufacturer, which suggested some benefit but this indication has not been pursued further.13 Inefficacy may be

due to poor penetration of imiquimod through the hyperkeratotic skin.

Podophyllotoxin, the major active ingredient of podophyllum, has not been assessed in randomised controlled trials for

the treatment of cutaneous warts.13 In the past, patients may have used a product marketed for plantar warts which contained

podophyllum resin 20% and salicylic acid 25% (posalfilin ointment), but this is no longer available in New Zealand. Podophyllum

can cause painful necrosis, particularly of normal skin adjacent to the wart, and is contraindicated in pregnant women

and young children.12

Topical zinc cream

The application of zinc to a wart is thought to augment immune function and/or assist in skin repair. Topical zinc cream

for the treatment of cutaneous warts has been assessed in two studies, which suggest it is superior to placebo treatment

and comparable to salicylic acid in efficacy.13 However, one of these studies used zinc sulphate which is not available

as a topical product in New Zealand.

A zinc oxide barrier cream 15 – 40% (general sale) may be trialled to treat a plantar wart, but there is limited evidence

of effectiveness.

Occlusive treatments

Covering a wart with adhesive tape or plaster has been anecdotally reported as a cure. Three clinical trials have assessed

its efficacy versus either cryotherapy as a comparison treatment, or a corn pad or moleskin wrap as a dummy placebo treatment.13

Although the first of these studies showed that duct tape was superior to cryotherapy, the two studies where duct tape

was compared to a corn pad or moleskin wrap found no statistically significant differences between treatments. Available

evidence does not support the notion that applying tape to a wart results in increased cure rates.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy has traditionally been used for plantar warts. However, clinical trials report low rates of cure and it

results in significant pain and blistering, reducing mobility for up to several weeks. A meta-analysis of trials of cryotherapy

(with liquid nitrogen or any other substance which induces cold damage to warts, e.g. dimethyl ether and propane [DMEP])

showed that freezing of cutaneous warts located on the hands or feet was no better than placebo.13 Studies of combination

treatment of cryotherapy with additional topical salicylic acid application do not support the idea that this treatment

is better than salicylic acid alone.13 Cryotherapy for plantar warts is therefore a non-evidence based intervention, associated

with significant morbidity.

N.B. Cryotherapy is less effective for treating plantar warts due to the thickness of the stratum corneum in this area.

It may be more effective for treating warts in other body sites, e.g. anogenital warts.

Hyperthermia

Raising skin temperature is thought to promote apoptosis (programmed cell death) and subsequently bring about an influx

of inflammatory and immune cells. In the context of wart treatment, these effects could theoretically improve HPV clearance.

However, given the specialised devices required (e.g. exothermic skin patches, radiofrequency heating apparatus’ or infrared

lasers) and the potential for burns with misapplication, the use of hyperthermia to treat plantar warts has limited application

in a general practice setting.

Surgical removal of warts

For some patients, plantar warts will persist despite multiple treatment approaches. Surgical removal of the wart may

be considered as a treatment of last resort. However, in many cases, surgery may also prove unsuccessful. Therefore, the

alternative option of ceasing active treatment of the wart can be discussed with the patient.

A plantar wart can be removed under local anaesthetic by shave, curette and electrosurgery, laser ablation or full-thickness

excision. Since plantar warts often arise on load-bearing tissue, the need to keep weight off the area of excision following

the procedure may cause reduced mobility and interference with daily living or work commitments. Adverse effects are those

expected from any minor surgery, including the risk of infection and post-procedural pain and scarring.

There is little data available on the success rates of surgical approaches to plantar wart treatment.

HPV vaccination

The quadrivalent HPV vaccine funded in New Zealand, Gardasil, protects against cervical cancer and genital warts, and

targets HPV-6, 11, 16, and 18. It is therefore not active against the HPV variants that are most commonly implicated in

plantar warts (HPV-1, 4, 27 and 57). However, there are some case reports where patients with recalcitrant plantar warts

have been successfully treated after the administration of quadrivalent HPV vaccine.16, 17 These cases suggest that the

vaccine induced a broader immune response. This approach has not been assessed in randomised controlled trials.