In this article

View / Download pdf

version of this article

The health of Pacific peoples in Aotearoa is “everybody's business”

Contributed by Dr Api Talemaitoga, Clinical Director, Pacific Programme Implementation, Sector Capability

and Implementation Directorate, Ministry of Health, Wellington

Pacific peoples in Aotearoa

New Zealand is home to approximately 250 000 New Zealanders of Pacific descent, who make up 7% of the country's total

population. Although collectively known as Pacific peoples or peoples of Pacific ethnic origin, these New Zealanders come

from approximately 20 different island groups, and have their own unique identities, languages, cultures and spiritual

beliefs. This impacts on their individual perceptions and collective interactions with New Zealand health services.

Opportunities to make a difference

Interacting with Pacific peoples provides unique opportunities and experiences for us as health practitioners:

- We have the opportunity to make a difference to the many poor health statistics that affect Pacific peoples

- We play an important role in ensuring Pacific peoples' experience of health service is a rich and fulfilling one that

makes a positive and long lasting impact on their health and the health of their families

Despite being able to access the same health services as other New Zealanders, Pacific peoples endure persistent disparities

in health outcomes and health care. Pacific peoples experienced the least improvement in age-adjusted all-cause mortality

from 1981 to 2004 of all ethnic groups (Figure 1).1

Pacific peoples' amenable mortality (deaths which should not occur given available healthcare technologies) has had

the least improvement. This indicates that healthcare for Pacific peoples has been less effective, and suggests that improvements

are needed in the quality of care.2

A large proportion of Pacific peoples' health disparity is due to their high chronic disease burden, particularly for

cardiovascular disease (CVD) and type 2 diabetes.1 The prevalence of diagnosed diabetes in Pacific peoples,

for example, is three times the prevalence reported in the total New Zealand population.3

Risk factors for these chronic diseases appear early in life. Pacific children, for example, have a higher prevalence

of obesity compared to the total population, and the prevalence nearly doubles between age two to four years and age five

to nine years.4

Figure 1: Trends in ethnic all-cause mortality rates (New Zealand Census Mortality Study)1

| Percentage decline 1981–84 to 2001–04 |

| |

Māori

|

Pacific |

Asian |

European/Other |

Males

|

25% |

14% |

58% |

42% |

Females

|

22% |

10% |

50% |

35% |

The challenges are many but not insurmountable

Alongside these persistent disparities, the Pacific population is undergoing significant demographic changes. The proportion

of Pacific peoples born in New Zealand has increased, with the largest proportion amongst Niueans, Cook Island Māori

and Tokelauan. The number of Pacific children born with dual or multiple ethnic ancestries has also increased significantly,

and the Pacific population is youthful compared to the total New Zealand population.5,6

There is evidence that health outcomes, such as CVD mortality, varies between Pacific groups, with the highest CVD mortality

rate among Cook Island Māori (approximately 1.66 times the Samoan rate).7 A recent needs assessment, which

compared a number of health indicators between the four largest Pacific groups in Counties Manukau DHB, found that a pattern

emerged – Samoans and Tongans shared similarities across several indicators; as did Cook Island Māori and Niueans.

For example, Samoans and Tongans were more likely to live in crowded households, and had higher rates of child hospitalisations

for respiratory-related illnesses, than Cook Island Māori and Niueans.8

As emphasised in 'Ala Mo'ui – Pathways to Pacific Health and Wellbeing 2010-2014 (the Ministry of Health's action plan

for Pacific health),9 all these aspects of diversity (place of birth, multiple ethnicities, and cultural variation

between Pacific groups) mean that services need to be particularly adaptable and innovative to respond to the varied needs

and preferences of Pacific peoples.

The principles emphasised in 'Ala Mo'ui, when working with Pacific peoples are that:

- Families and culture are important. They play a significant role in the health and well being of Pacific peoples.

- The key dimensions of quality, such as access, equity, cultural competence and patient-centeredness, are implicit

in the delivery of health and disability services

- Health and disability services need to work across other sectors like education, housing and social development

Pacific health providers have been effective at driving innovative approaches to increasing Pacific peoples' uptake

of health services (such as the MeNZB vaccine) and improving Pacific peoples' chronic care management. These health providers

have used “wrap-around” services to support the clinicians' treatment and advice and borrow heavily on the

principles of 'Ala Mo'ui.

While there is some growth in Pacific peoples' utilisation of primary care services, high rates of ambulatory sensitive

hospitalisations (hospital admissions that could have been avoided by provision of outpatient-based primary care) and

emergency department attendances10 reflect ongoing issues for Pacific peoples in accessing high quality, convenient

and timely primary health care. For example, the highest rate of “Potential Avoidable Hospitalisation” for

Pacific peoples in Auckland DHB in the 12 months to April 2010 was for cellulitis – essentially a condition that should

be largely treatable in primary care.

Cultural competence is a must for health practitioners if we are to make a real difference

The definition of “culturally appropriate” (also termed culturally-specific or culturally-adapted) health

care generally refers to any type of health care that is specifically tailored to the cultural needs of a minority group,

and/or is delivered by health workers from the same cultural group.11

Improving the health of Pacific peoples in New Zealand is everybody's business. All health practitioners will at some

stage encounter a Pacific person/family seeking health advice. The difference between a good practitioner and a great

practitioner is someone that aims to make the health interaction one that is not only positively memorable but also one

that encourages ongoing engagement to improve the health of the Pacific person and their family.

Being a great practitioner does not mean just complying with the Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act and Medical

Council requirements, but more as part of a collective responsibility that we all undertake to improve the health of all

New Zealanders of which Pacific peoples are a part. I am sure this can appear hard to fit in on top of everything else

in our already busy practices, but lessons learnt from research and the success of Pacific health providers may assist

us in better engaging our Pacific patients. These include:

- The use of community health workers to liaise directly with patients with health promotion and health literacy activities

- The more effective use of nurses to drive and run chronic care management clinics/programmes

- The strong empowerment of patients and their families to be more proactive in self management of their chronic conditions

- The use of or referral to a health practitioner of the same ethnic background or to someone who can explain important

health issues in a language specific to him/her

- The use of Pacific institutions such as churches and the engagement of lay preachers and ministers in the delivery

of the health messages to Pacific peoples

The New Zealand Medical Council has recently published a resource booklet; “Best health outcomes for Pacific peoples:

Practice implications”, that provides an understanding of the requirements for working successfully with Pacific

peoples, families and communities. Research shows that health practitioners who are familiar with their patient's cultural

differences are likely to offer improved patient care.

This booklet is available from: www.mcnz.org.nz (see Resources / Standards and guidelines / Cultural competence)

Ongoing quality improvements will contribute towards a more responsive health system

We need to continually monitor and evaluate any new initiatives being undertaken to ensure they are culturally competent,

cost effective and delivering better health outcomes for the Pacific populations we serve. This may also include ongoing

research which in turn puts New Zealand in an enviable position of leading the way in being culturally appropriate and

responsive to the health of minority populations within its borders.

Research already being undertaken on the strategies and aspects of culturally appropriate care includes:

- A review of strategies to improve health care quality for ethnic minorities, e.g. use of tracking and reminder systems

for improving the quality of preventive care and smoking cessation programmes, with nurses or community workers offering

screening services directly to patients.12 N.B. Many of the studies reviewed did not specifically evaluate

the duration of the effective strategies, which limits any conclusions that can be drawn.13

- A review of the effectiveness of culturally competent care (integrating cultural beliefs, values and practices into

the service delivery model), found it was associated with improved access and quality of health care among ethnic minorities.14

There are very few studies evaluating the effectiveness of culturally competent health care interventions in terms of

improved health outcomes.12

Take home message

Improving the health of Pacific peoples in Aotearoa is everybody's business and my challenge to all health practitioners

is to take action – to deliver health services in a way that is more responsive to the needs of the Pacific peoples we

serve. Think outside the square.

Pacific health providers are at the very heart of their communities and are making a tangible difference to Pacific

health. They are improving access to primary healthcare and specialists; they are increasing immunisation and screening

rates; they are educating communities in important preventative health messages; and they are helping to address the underlying

causes of ill health such as poor housing, education, nutrition and exercise.

The majority of us in non-Pacific practices (which care for over 80% of Pacific peoples in Aotearoa) need to take up

the challenge of matching this effort not only because we want to, but also because we have a responsibility to the Pacific

populations that are served by us collectively. We need to make it our business to deliver the best health care that can

bring real gains for all Pacific peoples - now and for future generations. Only then can we make real gains for the overall

New Zealand health system.

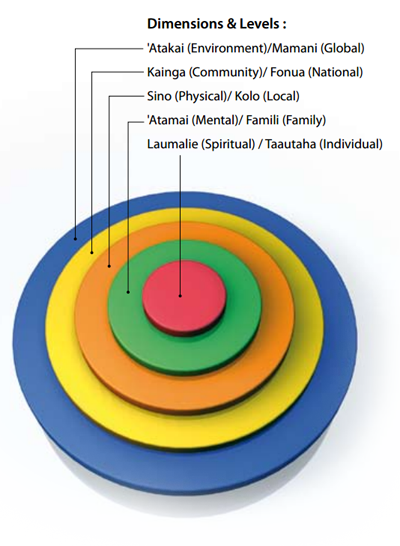

Fonua Model

Fonua: The cyclic, dynamic, interdependent relationship (va) between humanity and its ecology for the

ultimate purpose of health and wellbeing

Tu'itahi S. Fonua model. September, 2009. Available from: www.hpforum.org.nz (Accessed

Oct, 2010).

References

- Blakely T, Tobias M, Atkinson J, et al. Tracking disparity: Trends in ethnic and socio-economic inequalities in mortality,

1981-2004. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2007.

- Tobias M, Yeh L. How much does health care contribute to health gain and to health inequality? Trends in amenable

mortality in New Zealand 1981–2004. Aust N Z J Pub Health 2009;33:70-8.

- Ministry of Health. A Portrait of Health – Key results of the 2006/07 New Zealand Health Survey. Wellington: Ministry

of Health, 2008.

- Ministry of Health. New Zealand Food New Zealand Children: Key Results of the 2002 National Children's Nutrition

Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2003.

- Callister P, Didham R. Emerging demographic and socioeconomic features of the Pacific population in New Zealand.

In : Bisley A (Ed.). Pacific Interactions: Pasifika in New Zealand – New Zealand in Pasifika (pp. 13-40). Wellington:

Institute of Policy Studies, Victoria University of Wellington. 2008.

- Statistics New Zealand. QuickStats about Pacific peoples. 2007. Available from: www.stats.govt.nz/ (Accessed

Oct, 2010).

- Blakely T, Richardson K, Young J, et al. Does mortality vary between Pacific groups? Estimating Samoan, Cook Island

Māori, Tongan and Niuean mortality rates using hierarchical Bayesian modelling. Official Statistics Research Series

2000;5. Available from: www.statisphere.govt.nz/official-statistics-research.aspx (Accessed

Oct, 2010).

- Novak B. Ethnic-specific health needs assessment for Pacific people in Counties Manukau. Manukau City: Counties Manukau

District Health Board, 2007. Available from: www.cmdhb.org.nz/ (Accessed

Oct, 2010).

- Minister of Health and Minister of Pacific Island Affairs. 'Ala Mo'ui: Pathways to Pacific health and wellbeing 2010-2014.

Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2010.

- Carr J, Tan L. Primary Health Care in C&C DHB. Monitoring of Capital & Coast District Health Board's Primary

Care Framework. 2009. Available from: www.ccdhb.org.nz (Accessed

Oct, 2010).

- Kumpfer K, Alvarado R, Smith P, Bellamy N. Cultural sensitivity and adaptation in family-based prevention interventions.

Prev Sci 2002;3(3):241-6.

- Anderson L, Scrimshaw S, Fullilove M, et al. Culturally competent healthcare systems: a systematic review. Am J Prev

Med 2003;24(3S):68-79.

- Beach M, Gary T, Price E, et al. Improving health care quality for racial/ethnic minorities: a systematic review

of the best evidence regarding provider and organisation interventions. BMC Public Health 2006;6:104.

- Ministry of Health. Pacific Cultural Competencies: A literature review. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2008.