This year’s vaccine is different to previous years

It is too early to predict how severe the 2013 influenza season will be in New Zealand, however, a particularly severe

outbreak was seen in Canterbury in 2012 with a similar virus to that expected to be the dominant strain in all centres

this year. The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported an earlier than normal start to the Northern

Hemisphere season with rapid increases in the rates of influenza-associated hospitalisations and deaths among older people

in the United States.1

Influenza vaccination during the New Zealand 2013 season is more important than in recent years because this year the

vaccine contains two new strains that were not present in the 2010 – 2012 vaccines. A key message for health professionals

to deliver to patients is, therefore, that: “there may be strains of the flu circulating this year that vaccinations from

previous years are unlikely to provide protection against.”

The decision to change the vaccine composition follows a World Health Organisation (WHO) recommendation, after laboratory

testing showed changes in antibody reactions to circulating strains and also a change in the dominant viruses in circulation.2

The 2013 vaccine contains:3

- A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)-like strain

- A/Victoria/361/2011 (H3N2)-like strain (new)

- B/Wisconsin/1/2010-like strain (new)

Two vaccines are funded for 2013:

- Fluarix is approved for use in adults and children aged over six months

- Fluvax is approved for use in adults and children aged over five years, however, Public Health experts recommend that

Fluvax should not be given to children aged under nine years and should not be given to children who have a history of

febrile convulsions. This follows research showing increased rates of febrile reactions, including febrile convulsions

in this age group.4

Neither vaccine should be administered to people who have had anaphylactic reactions to any of the vaccine’s components.3 Fluarix

contains traces of gentamicin sulphate and Fluvax contains traces of neomycin and polymyxin.3 Both influenza vaccinations

are derived from hen eggs and may contain residual egg protein. People who have had a confirmed anaphylactic reaction

to egg protein should only be administered the vaccine under specialist supervision.3 People who have a non-anaphylactic

allergy to eggs can be administered the vaccine as normal. People who are acutely unwell or have a fever over 38°C should

delay having the vaccine until they are well.

How many doses of the vaccine are needed?

One dose is required for adults, children aged over nine years, or children aged between six months and nine years who

have already received an influenza vaccination in any previous year. Children aged between six months and nine years who

are receiving their first influenza vaccination should have two doses, at least four weeks apart.7 This is

because they may not have had contact with viruses with antigenic properties similar to the strains present in the vaccine

and are likely to require an additional dose to establish immunity.

Who is eligible for subsidised vaccinations?

The following eligible groups will receive a fully subsidised seasonal influenza vaccination if they visit their General

Practice clinic before 31 July, 2013:

- Anyone aged 65 years and over

- Anyone with cardiovascular, cerebrovascular or chronic respiratory disease, cancer, Type 1 or 2 diabetes or a specified

condition

- Pregnant women at any stage of gestation

A complete list of conditions that qualify a person for free vaccination is available

from: www.influenza.org.nz/?t=887

A complete list of conditions that qualify a person for free vaccination is available

from: www.influenza.org.nz/?t=887

N.B. People with asthma who do not require regular preventive medicines, those in remission from cancer, and people

with hypertension and/or dyslipidaemia without evidence of end-organ disease are not eligible for subsidised influenza

vaccination.

Who else should be encouraged to get vaccinated?

People with risk factors for exposure to influenza and its complications should also be encouraged to be vaccinated,

in particular children aged between six months and five years. Risk factors for influenza complications include:

- Pacific or Māori ethnicity

- Living in a low socioeconomic area or a crowded household

- Exposure to second-hand cigarette smoke

- Frequent illness

Women who intend to become pregnant during the influenza season and people travelling overseas, especially to the Northern

Hemisphere from October to May should also be encouraged to be vaccinated.

Healthcare workers are strongly recommended to be vaccinated because they have high exposure rates to influenza virus

and immunisation of healthcare workers may reduce patient morbidity.8 Endorsement of vaccination by healthcare professionals

can influence an individual’s decision to be vaccinated, even if they did not initially want to be.9 Influenza

vaccination is free to all staff employed by District Health Boards in New Zealand. In 2012, almost half of all employees

received an influenza vaccination. Rates were highest among doctors (57%) and lowest among midwives (37%).10

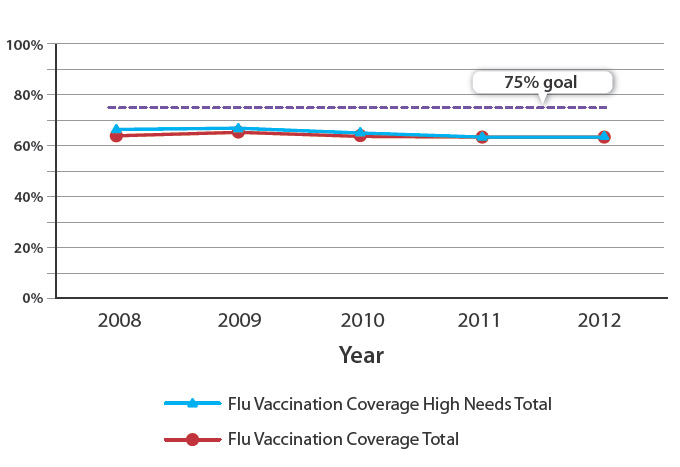

PHO Performance Programme – Influenza vaccination rates are decreasing

Influenza vaccination is a PHO Performance Programme (PPP) Indicator that accounts for 9% of the Performance funding;

3% for the total population and 6% for the high need population.5 High need populations include Māori and Pacific Peoples

and people living in Quintile 5 (most deprived) socioeconomic areas. The target is assessed by counting the enrolled

patients aged 65 years and over who have received an influenza vaccination during the most recent campaign (the numerator).

This number is then divided by the number of enrolled patients aged 65 years and over at the beginning of the most recent

campaign period (the denominator). Only vaccinations received by people aged 65 years and over are included in the PPP

results. PHOs that have a large number of people who decline offers of vaccination will therefore find it difficult to

meet the target.

The programme goal is for at least 75% of people aged 65 years and over at the end of the annual influenza vaccination

season to have received the influenza vaccine during the most recent campaign.5

The rate of influenza vaccinations has trended downwards over the past five years (Figure 1) for people aged 65 years

and over. The most recent data captured from July – September 2012 suggests that in 2013 rates may have stabilised, with

the national rate of vaccination dropping only slightly from 64.4% to 63.7%.6 However, this is more than 10% below the

programme goal of 75% coverage. It is important that the trend of declining influenza vaccination rates in New Zealand

is reversed. In 2012, no PHO achieved the target rate of 75%.

Figure 1: Influenza vaccination rates from 2008 to September 2012 for all people aged 65 years and over

in New Zealand5

Influenza vaccination is important for older people and women who are pregnant

Annual influenza vaccinations are important for people at increased risk of influenza-related complications. This is

not only because different strains of influenza may be in circulation each year, but also because antibody titre begins

to decline from one to two months post-vaccination.3 This is more pronounced in older people. Immunity levels

in people aged over 65 years have been shown to be significantly reduced at six months post-vaccination and may not be

sufficient to provide protection after this time.3, 11

Annual influenza vaccination may reduce cardiovascular risk. Mortality rates due to stroke and myocardial infarction

increase by 10 – 15% during winter.12 Recently, several studies have suggested that annual influenza vaccination

may have a cardio-protective effect. A meta-analysis, including over 290 000 patients, found that receiving an annual

influenza vaccination was associated with significant reductions in myocardial infarction (odds ratio 0.73), all-cause

mortality (odds ratio 0.61), and major adverse cardiac events (odds ratio 0.47).13 Another meta-analysis which

included over 30 000 participants aged over 55 years with known vascular disease, found that vaccination was associated

with a reduced risk of major vascular events when the virus in circulation was well matched to the vaccine.12

The pathophysiology of the possible effect of influenza on cardiovascular risk is not clear. Suggested mechanisms include

increased risk of plaque rupture, endothelial dysfunction, fever-associated tachycardia, impaired breathing, modulation

of blood clotting and immune and inflammatory processes.12, 13

Administering influenza vaccination during all trimesters of pregnancy is considered safe,14 and can be done

at the same time as pertussis vaccination occurs. Women who are pregnant and newborn infants are at increased risk of

influenza-related complications. Women with asthma or diabetes who are pregnant are three to four times more likely to

contract influenza and develop an influenza-associated illness.3 Neither Fluvax or Fluarix are approved for

use in infants aged younger than six months, however, young infants have high rates of hospitalisation from influenza.

Vaccination during pregnancy is therefore the best way to decrease a newborn infant’s influenza risk because it increases

antibody delivery, giving temporary protection to the infant via the placenta. Ideally all siblings and carers of infants

will also be vaccinated to provide a “cocoon of immunity” around the infant. Studies on the effectiveness of pertussis

vaccination have shown that immunisation of family members can provide protection to infants where there is a high prevalence

of disease within the community.15, 16 It is likely that these findings apply to other vaccine preventable

illnesses such as seasonal influenza.

Reducing the number of patients who decline influenza vaccination

When discussing influenza vaccination with patients who may be reluctant to be immunised, it is important to emphasise

the following points:

- There are two new strains of “the flu” in the vaccine this year, in recognition of changing circulating strains internationally

- Annual immunisation is likely to help to reduce the risk of an older person having a stroke or heart attack in the

future

- Immunisation helps to protect the families and friends of people who are immunised who may be more vulnerable to the

complications of influenza

Best Practice Tip: A standardised statement can be prepared for the practice to use when offering influenza vaccination

to patients. This may be of particular use when phoning patients who are unlikely to present for vaccination without

encouragement. The “Don’t let the flu get you!” website has template patient recall letters which may be useful when

contacting patients who have previously declined vaccination. Available from:

www.influenza.org.nz

Pneumococcal vaccination

Pneumococcal infection by the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae is a frequent cause of respiratory illnesses, e.g.

otitis media, bronchitis and sinusitis. Many people in New Zealand carry these bacteria without developing invasive disease.

However, serious complications such as pneumonia, meningitis and septicaemia can develop when S. pneumoniae invades normally

sterile tissue. Young children, older adults and people who are immunodeficient are most at risk of this occurring.

Four pneumococcal vaccines are licensed in New Zealand. Synflorix (10-valent) and Prevenar13 (13-valent) are conjugate

vaccines. Pneumovax23 and Pneumo23 (both 23-valent) are polysaccharide vaccines. Conjugate vaccines generate better quality,

more longer-lasting antibodies and have immune memory unlike polysaccharides. Conjugate vaccines are also more effective

when used as boosters.

The 10-valent Synflorix vaccine at age six weeks and age three, five and 15 months is funded for all infants as part

of the National Immunisation Schedule.17 Prevenar13 vaccine is used for children at high risk of complications,

followed by Pneumovax23 vaccine after age two years.17 High-risk children aged under five years (Table 1)

and all people with functional or anatomical splenectomy are eligible for fully subsidised vaccination with both Prevenar13

and Pneumovax23.

Pneumovax23 vaccination is recommended by the Ministry of Health, but not subsidised, for all people aged 65 years or

over and adults and children aged over five years at increased risk of invasive pneumococcal disease due to co-morbidity

or immunodeficiency (Table 1), who have not been previously immunised.17 The Immunisation Advisory Centre

also recommends that Prevenar13 be given eight weeks before Pneumovax23 in high-risk patients, to produce better immune

response.18 This is an ideal, but potentially expensive strategy for the patient.

Healthy people aged over 65 years generally require only a single dose of Pneumovax23, but those at high risk should

receive a second dose three to five years after their first dose.

There are no contraindications to pneumococcal vaccination other than a previous severe reaction to the vaccine or any

of its components. The safety of the vaccine has not been confirmed in pregnant women, therefore it is recommended that

immunisation occur following pregnancy, unless the risk of infection is substantial.17

For further information see: “The management

of community-acquired pneumonia”, BPJ 45 (Aug, 2012).

For further information see: “The management

of community-acquired pneumonia”, BPJ 45 (Aug, 2012).

| Table 1: Children and adults considered to be at high risk of pneumococcal disease17 |

| Children with these conditions/treatments are considered high risk* |

Adults with these conditions/treatments are considered high risk |

- Receiving immunosuppressive or radiation therapy

- Primary immune deficiencies or HIV

- Renal failure or nephritic syndrome

- Diabetes

- Down syndrome

- Organ transplants

- Cochlear implants or intracranial shunts

- Cerebrospinal fluid leaks

- Receiving long-term corticosteroid treatment and daily prednisone, or taking ≥ 20 mg prednisone per day

- Pre-term infants born prior to 28 weeks gestation

- Chronic pulmonary disease, including asthma treated with high-dose corticosteroids

- Cardiac disease with cyanosis or failure

|

- Aged over 65 years

- People with a history of invasive pneumococcal disease

- Functional or anatomical asplenia, e.g. sickle cell disease or splenectomy

- Chronic illness, e.g. chronic cardiac, renal or pulmonary disease, diabetes or alcoholism

- Immunocompromised, e.g. nephritic syndrome, lymphoma and Hodgkin’s disease, HIV

- Cerebrospinal fluid leak

- Cochlear implants

|

| * Eligible for funded pneumococcal vaccination if aged under five years |

Acknowledgement

Thank you to Dr Nikki Turner, Director, CONECTUS and The Immunisation Advisory Centre, University

of Auckland and Associate Professor Lance Jennings, Virologist, University of Otago, Christchurch and

Canterbury Health Laboratories, Canterbury DHB for expert guidance in developing this article.