Module 2: Early Medical Abortion

4. The EMA procedure

Pre-abortion assessment: focused medical history

A focused medical history needs to be taken to identify any contraindications for EMA and to aid in subsequent contraceptive choice.

Absolute contraindications for EMA include:

- Allergy to mifepristone or misoprostol

- Adrenal failure

- Poorly controlled severe asthma

- Steroid dependency

- Hereditary porphyria

- IUC in situ – it is acceptable to proceed if this is removed prior to commencing the abortion (New Zealand Aotearoa Abortion Clinical Guideline 2021, recommendation 2.2.1 states: “Remove intrauterine contraception prior to a medical abortion”)

- Known or suspected ectopic pregnancy

Relative contraindications for EMA include:

- Greater than 70 days of pregnancy

- Severe anaemia

- Serious or unstable health conditions such as ischaemic heart disease, uncontrolled epilepsy, renal failure, or hepatic failure

- A known bleeding disorder or taking anticoagulant medicines

A small proportion of patients experience heavy bleeding with an EMA which can be unpredictable in terms of timing. In a large study of EMA complications in Australia, there were 16 cases of haemorrhage (0.1%) from a total of 13,345 EMAs (11 of the 16 reported were haemorrhages with transfusion). It may be safer for a patient with severe anaemia, an unstable health condition or a bleeding disorder to have surgical management in a secondary service, or EMA in a hospital setting.

While the risk of heavy bleeding and cervical shock following an EMA are low, this increases with gestational age. It is essential to ensure people having an EMA in the community are safe and able to access emergency health care facilities if required. Determining whether this is the case needs to form a part of each individual’s consultation process. If there are social or practical barriers to emergency care access, then an at home EMA is not appropriate, and other options (e.g. early surgical abortion, or EMA in a different setting) should be offered as part of the shared decision-making process.

Examples of potential barriers to emergency care access:

- No reliable telephone access, or a limited ability to communicate with an emergency health service (e.g. language barriers)

- No transport or no adult companion at home

- Physical distance – e.g. being further than one hour from the nearest emergency health service.

Future fertility

No associations between induced abortion and ectopic pregnancy, infertility, placenta previa, or miscarriage have been found.

Pre-abortion assessment: Estimation of gestational age

New Zealand Aotearoa Abortion Clinical Guideline 2021:

- Recommendation 1.3.3: “Offer inpatient setting to people having a medical abortion before 10 weeks’ gestation if social or medical circumstances dictate”

- Recommendation 1.3.7: “Recommend selective ultrasound prior to first-trimester abortion if there is uncertainty about gestational age by clinical means, or if there are symptoms or signs suspicious for ectopic pregnancy”

- Recommendation 1.3.9: “Where there is clinical suspicion of ectopic pregnancy, refer the person to an early pregnancy unit/service”

- Recommendation 1.3.10: “Perform relevant physical examination as indicated”

Providers need to take a standard menstrual history focusing on the first day of the patient’s last menstrual period (LMP), including:

- How sure they are of the date

- If it was a normal menses for them, including any recent use of hormonal contraception

- If their menstrual cycles are regular, and if so, the average length of the cycle.

In studies of people seeking first trimester abortion who were reasonably certain of their LMP, self-reported gestational age correlated closely to ultrasound gestational age. A bimanual examination helps to estimate the gestational age – studies of pelvic examination to assess gestation agreed with ultrasound for 92% of experienced providers. The estimation of gestational age can be less accurate in the presence of obesity and fibroids.

If the gestational age based on the menstrual history and pelvic examination are consistent, and the person has no symptoms of pain or bleeding, then proceed with the EMA. Ultrasound should not be a barrier to abortion services and often has a cost. An ultrasound decision tool is available to download here.

The provision of point of care ultrasound in an abortion clinic by a trained provider is appropriate but not required for all people. A systematic review found no evidence that routine ultrasound before an EMA improved safety or efficacy compared with other diagnostic methods. If there are any concerns (e.g. about the pregnancy location or gestation), however, arrange for an ultrasound scan.

A transvaginal ultrasound can be performed if an intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) is not identified on a transabdominal scan. The roles of ultrasound in early pregnancy are to determine the pregnancy location (to confirm an IUP), confirm the number (single or multiple), document gestational age, and if appropriate, to detect a fetal heartbeat.

If providing an abortion via telehealth, see the module 1 section on telehealth.

EMA procedure, up to 10 weeks (70 days)

For an example consultation demonstrating how to explain the EMA process, click here.

The process of an EMA involves the patient taking mifepristone orally, followed by misoprostol administered vaginally, sublingually or buccally. These two drugs in combination cause the pregnancy to end as the uterus contracts to expel the pregnancy in a process similar to that of a miscarriage.

Both mifepristone and misoprostol should be given to the patient by the health practitioner providing abortion care. The health practitioner will be able to access mifepristone and misoprostol on a practitioner supply order (PSO). Mifepristone and misoprostol can also be prescribed if preferred.

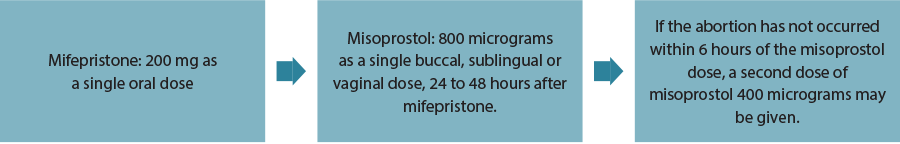

Dosing regimen

New Zealand Aotearoa Abortion Clinical Guideline 2021:

- Recommendation 2.2.2: “For medical abortion up to 10+0 weeks’ gestation, recommend combination regime that includes 200 mg oral dose of mifepristone and 800 micrograms dose of misoprostol”

- Recommendation 2.2.3: “For medical abortion up to 10+0 weeks’ gestation, offer buccal, sublingual or vaginal route of administration of misoprostol to reduce risk of ongoing pregnancy”

- Recommendation 2.2.4: “For medical abortion up to 10+0 weeks’ gestation, offer interval dosing (24–48 hours) of mifepristone and misoprostol”

Notes:

- The buccal and sublingual routes have a higher likelihood of side effects than the vaginal route. With the buccal and sublingual routes it takes about 20 minutes for the tablets to dissolve and the residue can be swallowed after 30 minutes.

- Patients should be advised that an EMA is more effective when the interval between mifepristone and misoprostol is 36 to 48 hours. If the interval is shorter, success rates are reduced. If the interval is longer, the likelihood of heavy bleeding occurring before the misoprostol dose is increased.

Side effects of misoprostol are usually self-limiting and include:

- Nausea (30%) and vomiting (20%)

- Diarrhoea (50%)

- Feeling warm or flushed, fever and chills (45%)

If the patient feels nauseated or has experienced hyperemesis prior to the abortion, offer an anti-emetic prior to taking the mifepristone. If the patient vomits within an hour of taking mifepristone recommend that another dose is taken.

Health practitioners should advise the patient that bleeding and cramping can sometimes start very quickly after misoprostol administration and should have started within 2–6 hours of taking the misoprostol. Bleeding will be heavier than a usual period. It will usually reach a peak over 4–6 hours, with cramps and bleeding heavier than their normal period with large clots; they may see some pregnancy tissue.

Patients need to know that ‘too much bleeding’ is soaking two maxipads per hour for more than two consecutive hours, or one pad an hour for 10 or more hours, or if they feel faint or dizzy. Some patients may experience light bleeding for up two weeks after the EMA.

Advise the patient to expect cramping and pain before and at the time of the expulsion of pregnancy tissue. More advanced gestation may be associated with more pain. Inform them about the different types of analgesics and when and how to take them.

Pain management and patient comfort

Non-pharmacological management of symptoms in EMA:

- Almost all patients will experience pain and cramping with abortion. The amount of pain varies greatly.

- A person having an abortion may feel anxiety, fear, or apprehension, which can increase sensitivity to pain

- A thorough explanation of what to expect is imperative to improve the person’s comfort with the procedure. Communicating this information in a respectful, non-judgemental way with attention to cultural sensitivity, cognitive ability, and social environment is essential.

- The 24-hour availability of a health professional by phone can reduce the anxiety felt experiencing EMA at home

- The presence of a support person, e.g. partner, friend or family member who can remain with the person during the process (if they desire it) can reduce anxiety

- A calm, soothing environment, use of music, or other distraction can be useful

- The use of a hot water bottle or heating pad can assist in comfort and pain relief

- For further information, see: Clinical Practice Handbook for Safe Abortion (WHO).

Pharmacological management of symptoms in EMA:

- Ibuprofen, celecoxib, and other NSAIDs are superior to paracetamol for the management of pain in EMA. Despite their anti-prostaglandin effects, they do not interfere with the action of misoprostol. A NSAID should be taken before or at the onset of cramping and continued regularly until the pain settles.

- RANZCOG recommend a single dose of 1600 mg ibuprofen initially, followed by 400–600 mg eighthourly, up to a maximum dose of 2400 mg in 24 hours while symptoms of pain persist

- There is less evidence over the value of opioids in the management of pain in EMA, although the consensus is that codeine or tramadol should be available as a back-up or add-on medicine to NSAID

- Nausea and vomiting can be present, either as a symptom of pregnancy or as a side effect of medicines. Offer an anti-emetic such as metoclopramide or ondansetron before the ingestion of mifepristone if the person is at risk of vomiting the medicine.

- Recommend another dose of mifepristone if the person vomits within one hour of taking the mifepristone

- Continued use of anti-emetics throughout the medical abortion for “as required” use is an option

- Loperamide may be useful for people with a predisposition to diarrhoea

Prophylactic antibiotics

Routine use of prophylactic antibiotics prior to EMA is not recommended. Prospective studies of first trimester EMA using mifepristone and a prostaglandin found the overall risk of infection was approximately 0.01% to 0.5%. Serious infection requiring hospitalisation is rare. There are no randomised controlled trials examining the effect of prophylactic antibiotics on medical abortion outcomes. In people who have not been screened for STIs, or results are unknown, consider offering prophylactic antibiotics.

Contraception after EMA

New Zealand Aotearoa Abortion Clinical Guideline 2021, recommendation 1.1.4 states: “Offer contraception counselling in accordance with New Zealand Aotearoa’s Guidance on Contraception”.

Recommendation 5.3.1 is “Offer contraception counselling in accordance with New Zealand Aotearoa’s Guidance on Contraception and criteria 1.7.1 in Section 1.7 Kua whai mōhio ahau, ā, ka taea e au te mahi whiringa | I am informed and able to make choices”.

Contraception should be discussed and offered at the time of the abortion consultation or appropriate referral made to obtain the method chosen by the patient. Contraceptive implants (Jadelle®) and injectables (Depo Provera®) can be administered on the day mifepristone is taken. Depo Provera injection at the same time as mifepristone may slightly increase the risk of ongoing pregnancy, although overall the risk is low.

Intrauterine contraception (IUC), including levonorgestrel containing intrauterine systems or copper intrauterine devices, should be inserted as soon as possible after the EMA when it is reasonably certain the person is no longer pregnant. Expulsion rates of IUCs inserted immediately post-abortion are higher. However, at six months more people are likely to have an IUC in situ compared to those who have delayed insertion.

Further information and guidance is available from Sexual Wellbeing Aotearoa (formerly Family Planning), Protected and Proud, and in New Zealand Aotearoa’s guidance on contraception (December 2020), section 2.4 Contraception after abortion. Medical eligibility criteria for contraception are provided by FSRH UK MEC and

WHO MEC.”

For a short presentation on contraception after EMA, click here.