Cervical cancer is now largely preventable through human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination and cervical screening programmes. Since the implementation of these programmes in New Zealand, fewer people are being diagnosed with and dying from cervical cancer. However, there are on average 171 new diagnoses (6.2 per 100,000 females; from 2015 – 2020) and 53 deaths (1.6 per 100,000 females; from 2015 – 2018)* caused by cervical cancer each year.†1, 2

*Mortality data are available for 2019, but are preliminary so have not been included. Mortality data for 2020 are not yet available.

†There are differences in published data. For consistency across the gynaecological cancer series, incidence and mortality data has primarily been obtained from the publication - Cancer: Historical summary 1948 – 2020.

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common type of cervical cancer in New Zealand (approximately 70% of all cases), followed by adenocarcinoma of the glandular cells lining the cervix (approximately 20% of all cases).3 Persistent HPV infection is necessary for the development of almost all cases of cervical cancer; other factors, however, also contribute to the incidence and progression (see: “HPV infection is responsible for almost all cases of cervical cancer”).4

People are generally infected with HPV shortly after the onset of sexual activity, but for most people the infection is transient.5 For those with persistent infection, progression to invasive cervical cancer is slow, with peak incidence between the ages of 25 and 44 years.6–8 The five-year survival rate from cervical cancer in New Zealand between 2010 - 2014 (latest data available) was 67.4%.9 Internationally, five-year survival rates vary widely but are generally better in high-income countries.9 Cervical screening programmes are therefore essential to identify precursor lesions and to prevent the development of invasive cervical cancer (see: “The early detection of cervical cancer is possible through cervical screening programmes”).

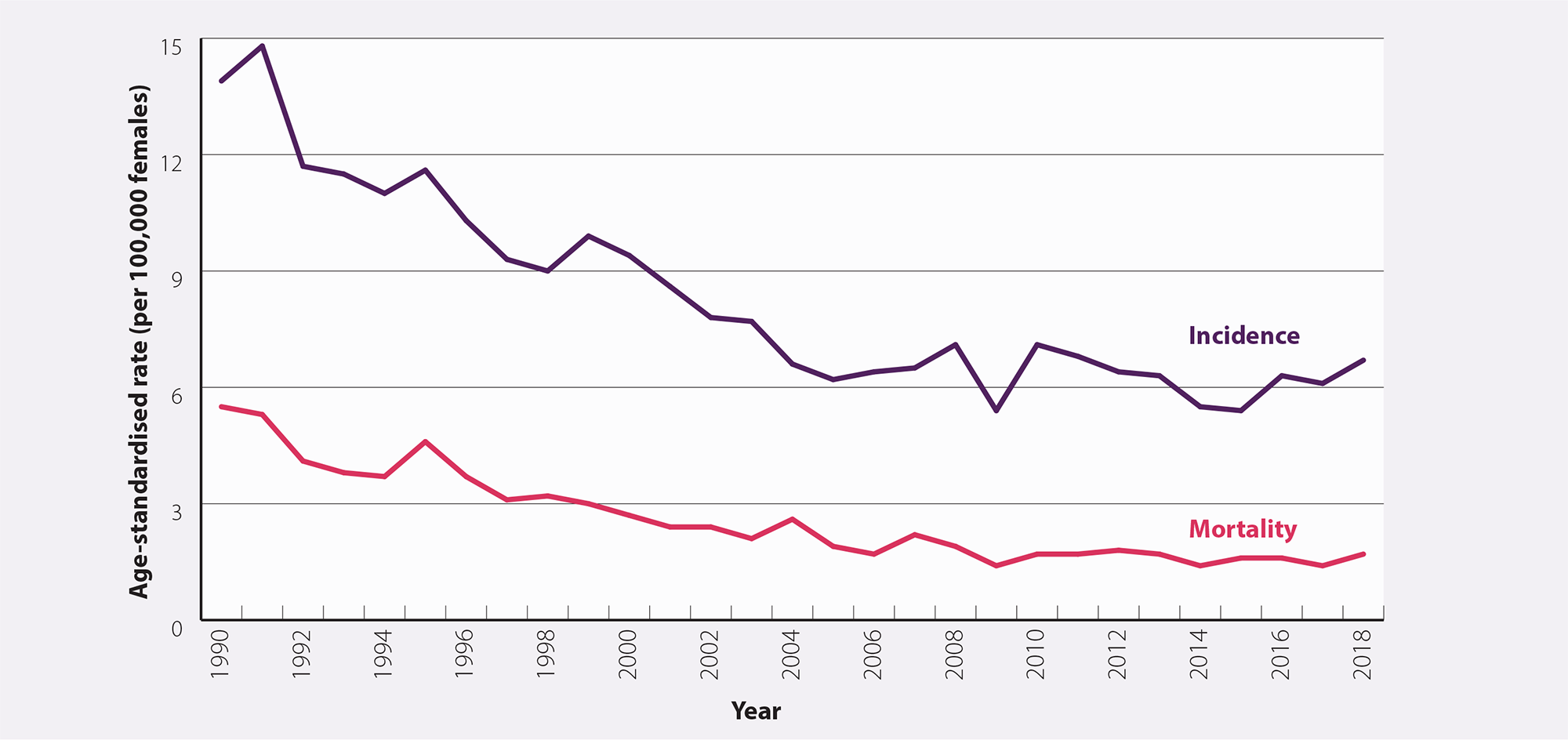

Incidence and mortality rates from cervical cancer have reduced over time

Since 1990, the overall incidence and mortality rates from cervical cancer in New Zealand have reduced from 13.9 and 5.5 per 100,000 females to 6.7 and 1.7 per 100,000 females in 2018, respectively (Figure 1).1 The most recent data available (2020) show that incidence is still declining (5.7 per 100,000 females).1 This has occurred primarily because of nationally co-ordinated cervical screening (established in 1990) and HPV immunisation (established in 2008) programmes, and well-established diagnostic and treatment services in New Zealand. Other factors such as reduced rates of smoking and improvements in sexual practices, e.g. condom use/barrier contraception, may also have contributed.10, 11

- Incidence and mortality rates from cervical cancer in New Zealand are similar to those in Australia and North America, e.g. Canada, but lower than those in Northern Europe, e.g. the United Kingdom.12

Incidence and mortality rates from cervical cancer are expected to decline even further over time with HPV testing, however, a transient increase in both the incidence of cervical cancer and demand for colposcopy services is likely after the initial transition due to the higher sensitivity of the test.* By 2035, the incidence and mortality rates from cervical cancer are expected to reduce by 32% and 25%, respectively, compared to 2018; this is equivalent to the prevention of 149 new diagnoses and 45 cervical cancer-related deaths in New Zealand.*

*Hall MT, Smith MA, Lew-J-B, et al. The combined impact of implementing HPV immunisation and primary HPV screening in New Zealand: transitional and long-term benefits, costs and resource utilisation implications. Gynecol Oncol 2019;152:472-9. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.10.045

Figure 1. Age-standardised incidence and mortality rates (per 100,000 females) for cervical cancer between 1990 and 2018 in New Zealand.1 N.B. Incidence data are available up to 2020 but have not been included in this graph for comparative purposes. Mortality data are available for 2019 but are preliminary so have not been included. Mortality data for 2020 are not yet available.

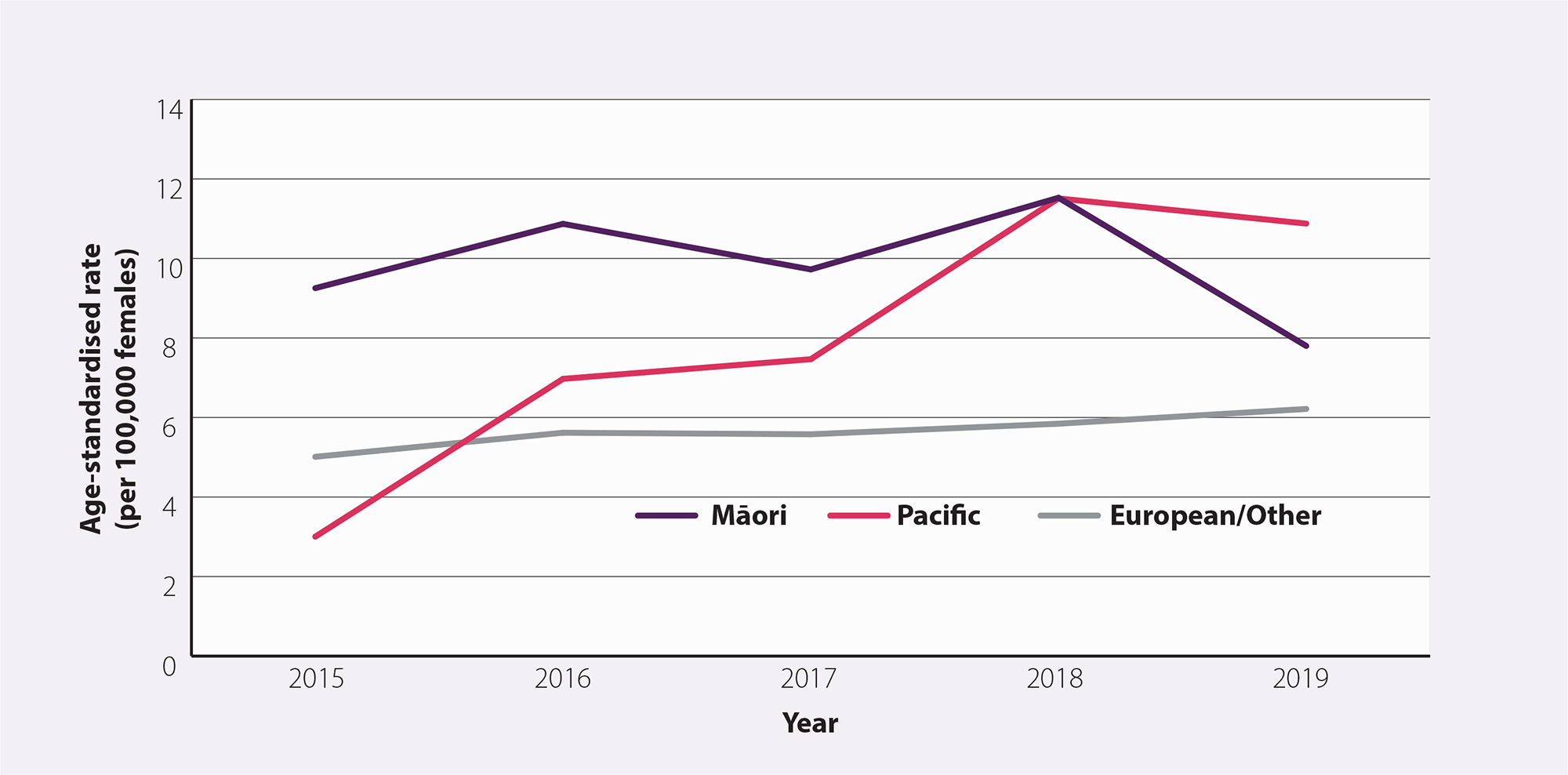

There are significant ethnic and socioeconomic inequities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality

Despite incidence and mortality rates from cervical cancer having reduced overall in New Zealand, Māori and Pacific peoples continue to have a higher incidence rate (Figure 2).2 Māori are also more than twice as likely to die from cervical cancer than Europeans.13 Cervical cancer is the second leading cause of death for Māori females aged 25 – 44 years.14

Figure 2. Age-standardised incidence rate (per 100,000 females) for cervical cancer by ethnicity between 2015 and 2019 in New Zealand.2 N.B. Incidence data by ethnicity are not yet available for 2020.

HPV DNA is present in 99% of all cervical cancers, but infection alone in people with a competent immune system is not sufficient to cause invasive cervical cancer.4, 10

Many risk factors (see below) for developing cervical cancer are also related to an increased risk of HPV and can be explained largely by the degree of HPV exposure countered by the degree of participation in cervical screening and HPV immunisation. It is difficult to determine which risk factors are independent of HPV infection.

Risk factors for the development of cervical cancer, in addition to HPV infection, include:

- Pre-cancerous cervical lesions. Females treated for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) have a two-to-three-fold increased risk of developing cervical cancer.15

- History of HPV-related vulval or vaginal dysplasia16

- Immunosuppression.10, 16, 17 Immune deficiency is associated with an increased risk of HPV infection and an increased rate of progression of cervical cancer.

- Low rates of cervical screening attendance16

- Low socioeconomic status10

- Younger age at sexual activity onset15, 16

- Increasing number of sexual partners or a high-risk sexual partner.15, 16 Females with more than six lifetime sexual partners are approximately three times more likely to develop cervical cancer compared to those with one sexual partner.10

- History of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).16 Particularly chlamydia or genital herpes.15

- Long-term oral contraceptive use.*10, 17 The risk of cervical cancer increases in proportion to the duration of oral contraceptive use (1.9-fold for every five years of oral contraceptive use) and reduces after cessation.15 It is unclear whether HPV exposure is a confounding factor.

- Young age at first full-term pregnancy.15 Females who give birth before age 17 years have approximately three times the risk of developing cervical cancer than those who give birth after age 25 years.10

- Increasing number of full-term pregnancies.15, 17 Females with more than five full-term pregnancies are approximately twice as likely to develop cervical cancer than females with one to two full-term pregnancies.10

- Smoking.16, 17 Smoking is an established co-factor (with HPV) for the development of pre-cancerous cervical lesions and cervical cancer. Females who smoke are approximately twice as likely to develop cervical cancer than females who do not smoke.10 The risk of cervical cancer increases in proportion with the duration and quantity smoked and reduces with smoking cessation.

- In utero exposure to diethylstilboestrol (DES).† Increases the risk of CIN 2 or higher.10

- Family history of cervical cancer. This is not usually a significant factor, except for an association with some very rare genetic conditions.

*In contrast, intrauterine devices (IUD) have been shown to protect against progression to invasive cervical cancer.10 The exact mechanism of protection is unknown, but a local cellular immune response from the IUD may help the body to clear the HPV infection.10 Protection begins after less than one year of use and persists after the device has been removed.10

†DES was used by approximately 1,000 pregnant females in New Zealand between the 1940s and 1960s to reduce the risk of miscarriage.18 Female offspring exposed in utero prior to 18 weeks’ gestation have an increased risk of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the cervix (and vagina), high-grade intraepithelial lesions (CIN 2/3) and cervical cancer. As DES has not been used during pregnancy for more than 45 years, the problem is declining.19

Most HPV infections resolve spontaneously

HPV is spread through skin-to-skin contact, most commonly through sexual activity.5 It is estimated that two-thirds of people (including males) become infected with HPV within three years of being sexually active, and up to 80% of people will be exposed to HPV at some stage in their lifetime.5, 20

There are over 200 types of HPV; 100 are relevant to the cervix. These are divided into high- and low-risk based on oncogenic potential.8 For most people (90%), infection is transient and spontaneously resolves within six to 24 months, but for others, HPV infection may become latent or persistent.4, 5, 10 Persistent infection with high-risk HPV types (see box) is generally asymptomatic but can lead to the development of cancers over time, including cervical, vulval, vaginal, anal, penile and oropharyngeal.5

High-risk HPV types 16 and 18 cause approximately 70% of all cervical cancers and up to 60% of precursor lesions.11

Other high-risk types are 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 52, 56, 58, 59 and 68. Low-risk types, particularly 6 and 11, are commonly associated with non-malignant lesions, e.g. genital warts.5

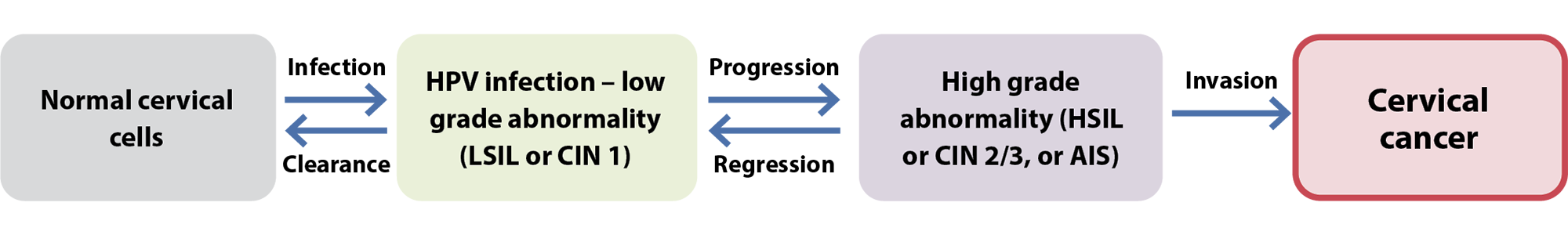

Cervical cancer progression. A small proportion of females with persistent infection with high-risk HPV types, develop pre-cancerous cervical lesions that can progress to invasive cervical cancer if left untreated (Figure 3).4, 5 However, fewer than one-third of low grade pre-cancerous lesions progress to high-grade lesions and the majority of those do not progress to cervical cancer.10 Regression of pre-cancerous cells to normal cells can also occur, usually within one to two years.4 Progression to invasive cervical cancer is slow, taking up to 20 years, which provides multiple opportunities for the early detection of pre-cancerous cervical lesions through cervical screening programmes (see: "National Cervical Screening Programme").5, 19

Figure 3. An overview of the development of cervical cancer from infection to invasion.

LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; AIS, adenocarcinoma in situ

Prophylactic HPV vaccination is the primary prevention strategy for cervical cancer

HPV vaccination can protect against the acquisition of new HPV infections; it does not reduce the progression of established cervical lesions.5 It is estimated that 92% of cancers caused by HPV can be prevented by vaccination with Gardasil 9 if administered prior to HPV exposure.19

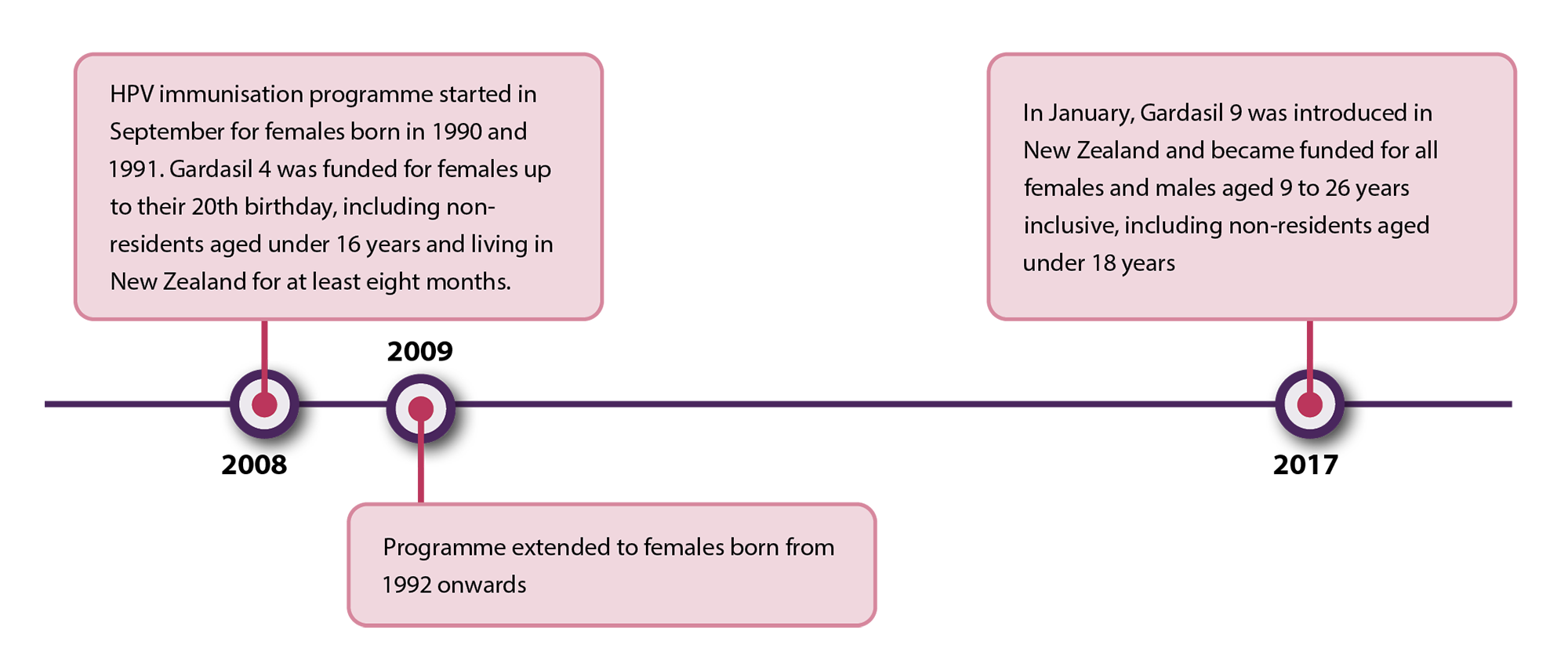

The HPV immunisation programme was first launched in New Zealand in 2008 (Figure 4). A retrospective population-based study (including 104,313 people) in New Zealand using data from 2010 – 2015 found that females aged 20 – 24 years who had at least one dose of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine (Gardasil 4) prior to age 18 years, had a 25% lower incidence of high-grade cervical cytology and 31% lower incidence of high-grade histology compared to those who were unvaccinated.21

Figure 4. Timeline detailing significant events in the HPV immunisation programme in New Zealand.22

Gardasil 9 has been used in New Zealand since 2017 and protects against nine types of HPV (6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58); seven of which cause HPV-related cancers and two cause genital warts.5 HPV vaccination is recommended for all females and males ideally before the onset of sexual activity, and is funded for eligible people aged 9 – 26 years inclusive*.5 School immunisation programmes and general practices generally offer HPV vaccination to students in Year Eight (around age 12 years). The vaccine can be administered (not funded) to people aged 27 years and older if they have not been vaccinated before and are likely to benefit, e.g. people who are newly sexually active, men who have sex with men.5

Expert tip. Vaccinating people who have already commenced sexual activity is still recommended as even if they have been infected with one or several HPV types, there are 14 high-risk types associated with cervical cancer, and so it is unlikely that someone will have been infected with all of them.

N.B. Gardasil 9 is registered for use in females aged 9 – 45 years and in males aged 9 – 26 years. However, there are no theoretical concerns that the efficacy or safety of the vaccine in males aged up to 45 years will differ significantly from females of the same age or younger males.5

*If the course is started prior to the patients 27th birthday, the rest of the course is funded. For further information on funded indications, see: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/immunisation-handbook-2020

Despite the HPV immunisation programme being effective at reducing the prevalence of HPV infection and the incidence of cervical cancer, vaccination cannot eliminate cervical cancer entirely as people may:5

- Not have been eligible for vaccination, did not opt to be vaccinated or did not complete the course*

- Mostly, only people born after 1990 have been vaccinated; the vaccination rate among the eligible population (including males) born in 2008 (most recent data) was 56%; 75% of people had at least one dose.23 Vaccination rates were highest among Asian peoples (62%), followed by European/Other (59%), Pacific peoples (52%) and Māori (50%).23 Coverage needs to be 75 – 80% to achieve herd immunity.24

- Have been exposed to HPV prior to being vaccinated

- Have been infected with a high-risk type of HPV that was not covered by the vaccine (Gardasil 9 only covers seven of the 14 high-risk HPV types known to be associated with cervical cancer)

- Have been infected with a low-risk type of HPV that very rarely, can cause cervical cancer

- Have a non-HPV associated cervical malignancy

*In rare cases, people may not develop immunity despite being vaccinated5

Therefore, all eligible people including those who have been vaccinated against HPV, should undergo regular cervical screening to detect any pre-cancerous lesions and prevent progression to invasive cervical cancer.

National Cervical Screening Programme

Most females with pre-cancerous cervical lesions are asymptomatic and therefore, screening programmes are required to detect these pre-cancerous changes early (see box for symptoms and signs of invasive cervical cancer).7, 19 Since the National Cervical Screening Programme (NCSP) began in 1990, overall incidence and mortality rates from cervical cancer have reduced by approximately 50% and 60%, respectively (Figure 1).20 Rates have declined among all ethnicities, particularly for Māori, however, inequities still exist.3, 20

In line with best practice, HPV testing is now the primary cervical screening test in New Zealand, replacing the previous cytology-based programme which relied on the microscopic analysis of cells taken from the cervix during a speculum examination, utilising liquid-based cytology (LBC).25 The new pathway, which was implemented on 12th September, 2023, is called HPV Primary Screening (see: “An overview of HPV Primary Screening”). Most people will be able to have a HPV test when they are next due for cervical screening, however, transitioning to the new programme may be slightly different for some, e.g. those with previous high-grade results. For specific details on transitioning patients onto the new cervical screening pathway, see: www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/assets/Our-health-system/Screening/HPV-Primary-Screening/clinical_practice_guidelines_final_version_1.1.pdf#page=15

A HPV test detects the presence of DNA from high-risk HPV types that are known to cause cervical cancer.25 A PCR test is performed on the sample, including partial genotyping to differentiate HPV Types 16 and 18 from the additional 12 high-risk HPV types that are collectively reported as HPV Type Other.25 This can identify people at risk for abnormal cell changes and, therefore, those who require further testing. HPV testing offers up to 70% greater protection against the development of invasive cervical cancer, compared to cytology-based screening alone.26 Cytology will continue to be used in the follow-up of people who have HPV detected, and in some clinical scenarios as part of a co-test, e.g. people with symptoms or needing a test of cure.

The NCSP recommends five-yearly (or three-yearly if immune deficient) cervical screening following a “HPV Not detected” test for females* aged between 25† and 69 years who have ever been sexually active.25 Ensure patients understand that being sexually active involves any form of sexual contact, i.e. it is not restricted to sexual intercourse. Screening is extended for people aged 70 – 74 years who are unscreened or under-screened.25

*The NCSP refers to the eligible screening population as “participants” and define this as anyone who has ever been sexually active and has a cervix

†Prior to 2019, the start age was 20 years; people aged < 25 years who have already started cervical screening should continue to be recalled and managed in the same way as those aged 25 – 69 years.

Exiting the NCSP

People can exit the cervical screening programme from age 65 years (or age 67 years if immune deficient) if they have a “HPV Not detected” result and are not in follow-up for abnormal cytology or histology.25

People aged 70 – 74 years who have been unscreened or under-screened prior to age 70 years should have a HPV test and can exit the programme once HPV is not detected.25 This includes people transitioning from the cytology-based programme without two consecutive normal cytology results after the age of 62 years, and people who have already transitioned to the HPV Primary Screening programme who have not had a negative HPV test in the five years prior to age 70 (or three years prior to age 70 if immune deficient).25

If HPV is detected (any type) in a person aged 70 – 74 years who is undergoing exit testing, they should be referred directly for colposcopy.25 Vaginal oestrogen is recommended to be applied daily for three weeks prior to colposcopy for people in this age group.25

Cervical screening attendance has declined over time

N.B. Cervical screening now occurs every five years for most people; rates of cervical screening attendance are likely to change over time with HPV testing, particularly due to the option of self-testing.27

Three-yearly cervical screening attendance in New Zealand has been steadily declining over time, with an accelerated rate of decline during the COVID-19 pandemic, from 76% of eligible people in 2008, to 67% in June, 2022.28

There are considerable inequities in cervical screening attendance; in June, 2022, the national three-year coverage was 57.7% for Asian, 55.7% for Pacific peoples and 54.9% for Māori, compared to 74.4% for European/Other.28 People who live in low socioeconomic areas also have lower rates of attendance for cervical screening.19 Low rates of cervical screening attendance is concerning as most cervical cancers in New Zealand occur in people who are not regularly screened.19

Reducing barriers to cervical screening

The following strategies may be used to enhance cervical screening attendance (N.B. Some of these barriers may be overcome with the option of HPV self-testing):29, 30

- Discuss or offer (if time allows) screening to people who are overdue when they present for any reason, i.e. opportunistic screening

- Ask patients how they would like to be contacted with reminders, and note this in their clinical record

- Provide culturally appropriate educational materials on the importance of cervical cancer screening in waiting or consultation rooms, e.g. healthed.govt.nz/search?type=product&q=cervical+screening

- Assess eligibility for funded cervical screening (some regions may offer low-cost cervical screening for people who are not eligible for funded screening; check local HealthPathways for funding initiatives in your region)

- Consider whether your practice could offer occasional dedicated times for people to attend for cervical screening, e.g. a monthly evening or weekend session, or a weekly morning or early evening slot. N.B. We acknowledge that this might not be achievable in the current COVID-19 environment.

- Take time to ask the patient if they have any questions or concerns about the cervical screening procedure. Not knowing what to expect or the fear of finding cancer can be a barrier to access for some people. Address any concerns and reassure patients as appropriate.

- Address any issues that may cause difficulties in taking the sample, e.g. initiate vaginal oestrogen cream for people who are oestrogen deficient

- Minimise embarrassment or vulnerability associated with taking a LBC sample by discussing ways that could make the patient more comfortable, e.g. bringing a support person, choosing their sample taker (gender, ethnicity), appropriate covering of the patient and pulling curtains around the bed to ensure privacy. Explaining each step of the process as it is performed can be helpful to make the patient more relaxed.

- Provide reassurance about confidentiality. Some people may not want to attend cervical screening because it acknowledges that they are sexually active. Reassure these patients that the consultation is entirely confidential and remind them that they do not need to disclose to others the reason for their appointment.

Invasive cervical cancer

Symptoms of cervical cancer can be subtle and may be attributed to other gynaecological conditions.31 The presence of multiple symptoms and signs should raise clinical suspicion for cervical cancer:7, 10, 15 , 31

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding, including inter-menstrual, post-menopausal or post-coital bleeding; bleeding is the most common symptom of cervical cancer

- Unusual and persistent vaginal discharge

- Dyspareunia

- Non-specific pelvic or low back pain or pressure

- Abdominal pain

- Loss of appetite, weight loss or fatigue

- Bladder changes, i.e. urinary tract infection, incontinence, haematuria

- Bowel changes, e.g. haematochezia

- Unexplained laboratory results, e.g. low haemoglobin or ferritin, high white blood cell count (N.B. Biochemical changes are often not present.)

In advanced cervical cancer, the combination of lower limb oedema, flank pain and sciatica suggests pelvic sidewall invasion.16 Passage of urine or faeces through the vagina suggests invasion of the bladder or rectum.16

Perform a pelvic examination, including speculum examination, and take a LBC sample for both HPV and cytology testing* for patients with suspicion of cervical cancer.15, 25 Palpable inguinal or supraclavicular lymph nodes suggest advanced cancer.15, 16 If the patient has symptoms or signs of cervical cancer or if the appearance of the cervix is abnormal, refer to or discuss with a colposcopy service, irrespective of HPV and cytology results.25 Check local HealthPathways for specific referral information.

*Note the presence of symptoms and that a co-test is required on the laboratory form otherwise cytology will not be performed unless HPV is detected

A HPV test detects the presence of DNA from high-risk HPV types that are known to cause cervical cancer.25 This can identify people at risk for abnormal cell changes and, therefore, those who require further testing.

A HPV test can be performed from one of the following samples:25

- A vaginal swab taken by the patient (i.e. a self-test)

- A vaginal swab taken by a screen taker*

- Liquid based cytology (LBC) taken by a cervical sample taker. This sample type will only be tested for HPV initially in routine screening. If HPV is detected, reflex cytology will then be performed.

* The screen taker workforce for HPV testing includes (as of November, 2024):

HPV testing (including self-testing) requires clinical oversight including a discussion about which method of sample taking is most appropriate for the patient (see: “How HPV testing works”). A vaginal swab sample will not be suitable in some cases (Table 1).

If the cervix is visually abnormal upon cell collection during a speculum examination, the patient should be referred for colposcopy irrespective of the HPV and cytology test results.20

Routine cervical screening will occur every five years for most people after a “HPV Not detected” test result; people who are immune deficient should be screened every three years (this needs to be changed on the NCSP register and indicated on the laboratory form; see: “Cervical screening in special clinical circumstances”).25

A brief HPV testing summary guide is available from: bpac.org.nz/2023/hpv-testing-guide.aspx

Table 1. Scenarios where a liquid-based cytology (LBC) sample is required or may be a

pragmatic choice over a vaginal swab sample.25

LBC sample required for both HPV and cytology testing

Note clinical details, e.g. specific symptoms, test of cure, on the laboratory form otherwise cytology will not be performed unless HPV is detected |

LBC may be a pragmatic choice

(so that if HPV is detected, a return visit is not required as reflex cytology will be performed on the same sample) |

People with symptoms |

People with previous low-grade results who have not returned to regular screening |

People needing a test of cure, e.g. after treatment for a high-grade cervical lesion or HPV positive adenocarcinoma in situ |

At 12- or 24-month follow-up after a “HPV Detected Type Other” result |

People with a history of completely excised adenocarcinoma in situ that was HPV negative or HPV status unknown |

People with immune deficiency – as they need to be referred for colposcopy if HPV of any type is detected and where possible this should be informed by cytology results |

People who may find follow-up difficult, e.g. live rurally, unlikely or unable to return |

Cervical screening in special clinical circumstances

Pregnancy. Cervical screening (including from a LBC sample* if needed) is safe during pregnancy and should be performed if the person is due or overdue for screening or is recommended to have a follow-up test.25 Patients should still be referred for colposcopy during pregnancy if required, but biopsy may be delayed.25

Pregnancy. Cervical screening (including from a LBC sample* if needed) is safe during pregnancy and should be performed if the person is due or overdue for screening or is recommended to have a follow-up test.25 Patients should still be referred for colposcopy during pregnancy if required, but biopsy may be delayed.25

*A cervibroom should be used as a cyto- or combi-brush can cause bleeding which may be distressing to the patient during pregnancy

The post-partum period is not an ideal time for cytology-based screening as the transitional lack of oestrogen makes the cytology more difficult to interpret (HPV testing can be done post-partum).25 If cytology and/or colposcopy is required post-partum, it should be performed at least six weeks after delivery.25 Females who are post-natal or breastfeeding may experience vaginal dryness or atrophy due to lower oestrogen levels; consider a course of vaginal oestrogen if cervical screening or colposcopy is required.25

Immunodeficiency. Females who are immune deficient require more frequent cervical screening than every five years due to an increased risk and prevalence of HPV infection, cervical lesions and cervical cancer.17, 25 People who are immune deficient should be screened every three years after a “HPV Not detected” result.25 If HPV is detected (any type), the patient should be referred directly for colposcopy (informed by cytology results where possible).25

Immunodeficiency. Females who are immune deficient require more frequent cervical screening than every five years due to an increased risk and prevalence of HPV infection, cervical lesions and cervical cancer.17, 25 People who are immune deficient should be screened every three years after a “HPV Not detected” result.25 If HPV is detected (any type), the patient should be referred directly for colposcopy (informed by cytology results where possible).25

Consider a HPV test for people aged between 20 and 24 years if they have been immune deficient for more than five years and have been sexually active.25

Ensure an appropriate recall is set on your PMS for patients eligible for cervical screening who have immune deficiency. This also needs to be changed on the National Cervical Screening Register and indicated on the laboratory form. You can contact the Register team to add immune deficiency as a medical condition on the patient’s record which will flag them as requiring three-yearly screening, otherwise the default recall will be five years.

For information on specific cervical screening recommendations for people with immune deficiency, see: www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/assets/Our-health-system/Screening/HPV-Primary-Screening/clinical_practice_guidelines_final_version_1.1.pdf#page=76

Hysterectomy. Cervical screening is recommended in some instances after hysterectomy, unless the hysterectomy was for benign reasons and the patient has a normal screening history.25 For specific recommendations, see: www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/assets/Our-health-system/Screening/HPV-Primary-Screening/clinical_practice_guidelines_final_version_1.1.pdf#page=64

Hysterectomy. Cervical screening is recommended in some instances after hysterectomy, unless the hysterectomy was for benign reasons and the patient has a normal screening history.25 For specific recommendations, see: www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/assets/Our-health-system/Screening/HPV-Primary-Screening/clinical_practice_guidelines_final_version_1.1.pdf#page=64

In utero exposure to diethylstilboestrol.* Offer referral to colposcopy (if not previously done) to determine whether the patient has vaginal adenosis.25 Annual colposcopic assessment is recommended for people with vaginal adenosis who were exposed in utero to DES.25 If vaginal adenosis is absent, routine interval cervical screening is appropriate.25

In utero exposure to diethylstilboestrol.* Offer referral to colposcopy (if not previously done) to determine whether the patient has vaginal adenosis.25 Annual colposcopic assessment is recommended for people with vaginal adenosis who were exposed in utero to DES.25 If vaginal adenosis is absent, routine interval cervical screening is appropriate.25

*See earlier note

Transgender and non-binary people. Transgender men and non-binary people with a cervix or vagina are recommended to participate in the cervical screening programme to the same extent as cisgender females.34 Additional attention may need to be given to addressing concerns around the testing procedure, privacy and recalls. N.B. There is no evidence that use of testosterone modifies the risk of cervical cancer, however, long-term use may cause vaginal atrophy which can alter cytology results; some patients may wish to be prescribed a course of vaginal oestrogen cream prior to cytology testing.35 Some patients may be offered a course of vaginal oestrogen cream prior to HPV testing if they are experiencing vaginal dryness, but a swab cannot be taken if the sample will be obscured by cream.

Transgender and non-binary people. Transgender men and non-binary people with a cervix or vagina are recommended to participate in the cervical screening programme to the same extent as cisgender females.34 Additional attention may need to be given to addressing concerns around the testing procedure, privacy and recalls. N.B. There is no evidence that use of testosterone modifies the risk of cervical cancer, however, long-term use may cause vaginal atrophy which can alter cytology results; some patients may wish to be prescribed a course of vaginal oestrogen cream prior to cytology testing.35 Some patients may be offered a course of vaginal oestrogen cream prior to HPV testing if they are experiencing vaginal dryness, but a swab cannot be taken if the sample will be obscured by cream.

Best Practice Tip. If you change the gender of a patient who is biologically female in their clinical record, ensure they remain in the practice recall system for cervical screening and enrolled with the National Cervical Screening Programme.

How HPV testing works

When a patient is due for cervical screening, a consultation with a screen taker is required to discuss the HPV test, including:

- How the test works

- Obtaining informed consent (record in patient notes)

- Whether a vaginal swab sample is suitable or if a clinician-taken LBC sample (by a cervical sample taker) is preferred/needed

- Self-testing, including the benefits and risks (see below) and guidance on how to self-swab

- What follow-up to expect if HPV is detected

Practice Point: If STI testing is indicated at the time of cervical screening, this must be performed on a different swab to the one being tested for HPV.

HPV self-testing is usually carried out at the practice. However, at the discretion of the screen taker, a patient may do their HPV self-test at another location, e.g. their home, but must return the sample to the practice. It is the screen taker’s responsibility to follow-up that this has occurred (the time required for this follow-up may be a factor in the decision to offer off-site testing).

A PCR test will be performed on the sample, including partial genotyping to differentiate HPV Types 16 and 18 from the additional 12 high-risk HPV types that are collectively reported as HPV Type Other.25 If HPV Type 16 or 18 is detected, referral to colposcopy is indicated.25 If HPV Type Other is detected, management depends on cytology results (see: “Managing HPV test results”).25 If HPV Type Other is detected on a vaginal swab, a return visit for a LBC sample to be taken by a clinician (i.e. cervical sample taker) with a speculum is required, as cytology cannot be performed from a vaginal swab sample.

The benefits and risks of HPV self-testing

HPV self-testing has been shown to have equivalent accuracy for detecting HPV as a clinician-taken sample, and is expected to increase the uptake of cervical screening in those who have previously been reluctant to screen.13, 25 HPV self-testing has the potential to reduce the equity gap by halving the number of Māori females who are under-screened or never screened.13

Although the option of self-testing is an important strategy to increase the uptake of cervical screening, there are still benefits to a clinician-taken LBC sample. Compared to cytology-based cervical screening, risks of HPV testing from a vaginal swab include missed opportunities for the clinician to detect other health concerns such as STIs or abnormal pathology, and the patient not attending follow-up after HPV Type Other is detected.13, 27

Regardless of the sample collection method, a full consultation with a clinician, including physical examination should still be encouraged as good clinical practice and as a way to address opportunistic health issues or patient concerns.27 Cervical screening may also be an appropriate time to ask about domestic partner abuse or harm, including sexual violence.

If the patient opts for self-testing, reinforce follow-up expectations if HPV Type Other is detected and encourage them to return to primary care if they experience any gynaecological concerns.

Getting a good sample

The role of lubricant when obtaining a LBC sample. Use of lubricant on the speculum can result in unsatisfactory cervical cytology results; lukewarm water may be a suitable alternative. If a lubricant is required, apply a water-based product sparingly to the outer sides/exterior of the speculum blades, making sure to avoid the tip so that lubricant does not get into the LBC vial.32

The role of vaginal oestrogen cream. A course of vaginal oestrogen can be offered prior to cervical screening (LBC or vaginal swab sample) for people who are post-menopausal, post-natal or breastfeeding, or for other people experiencing vaginal dryness, including transgender males. However, a swab cannot be taken if the sample will be obscured by cream. Vaginal oestrogen cream can reduce the discomfort of a taking a sample (either with a swab or during a speculum examination) in a person with vaginal dryness/atrophy, and can improve visualisation of the cervix, the quality of the cervical sample and diagnostic accuracy of LBC.8, 33

Instruct patients to insert the cream each night for two to three weeks prior to the test and to stop one to two days before the appointment.8, 25 N.B. Patients should also stop use of other vaginal applications, e.g. anti-fungal creams, spermicides, prior to the appointment.

Menstruation. Cervical screening (with a vaginal swab or LBC sample) can be done during menstruation (although not preferable), but occasionally excessive blood on the sample may cause invalid results and a repeat test will be needed.

Self-swabbing technique. Provide clear self-swabbing instructions and ensure patients understand that they must insert the tip of the swab 4 – 5 cm into the vagina and rotate the swab around the vagina making contact with the sides of the walls for approximately 20 seconds before removing. Instructions can be downloaded or ordered from HealthEd or your laboratory provider if needed.

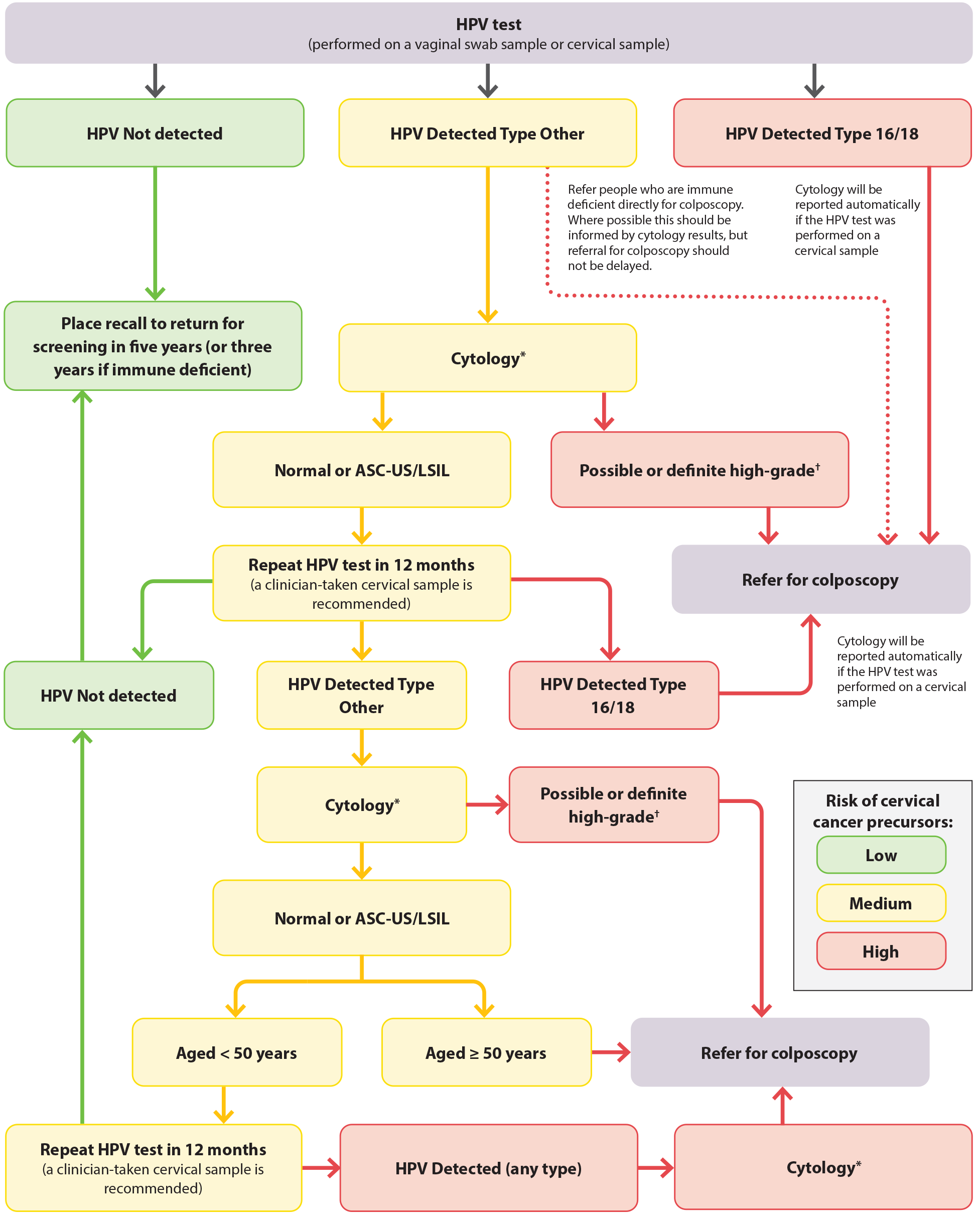

The results from HPV testing will either be: HPV Not detected, HPV Detected Type 16, HPV Detected Type 18, HPV Detected Type Other (some laboratories will state which type[s]), Invalid (sample processed but no result) or Unsuitable for analysis (e.g. not processed because the sample was leaking).25 The report will include an overall recommendation. If HPV testing was facilitated by a HPV screen taker or HPV screening kaimahi, the overseeing clinician (the “responsible clinician”) is responsible for the management of the patient’s results, e.g. arranging appropriate referrals, follow-up and recalls. See Figure 5 for an overview of the management of HPV test results.

If HPV of any type is detected in a person aged 70 – 74 years who is undergoing exit testing, they should be referred directly for colposcopy.25 Vaginal oestrogen is recommended to be applied daily for three weeks prior to colposcopy for people in this age group.25

If HPV of any type is detected in a person aged 70 – 74 years who is undergoing exit testing, they should be referred directly for colposcopy.25 Vaginal oestrogen is recommended to be applied daily for three weeks prior to colposcopy for people in this age group.25

If HPV of any type is detected in a person who is immune deficient, they should be referred directly for colposcopy.25 Where possible this should be informed by cytology results, but referral for colposcopy should not be delayed.25

If HPV of any type is detected in a person who is immune deficient, they should be referred directly for colposcopy.25 Where possible this should be informed by cytology results, but referral for colposcopy should not be delayed.25

*Cytology cannot be performed from a vaginal swab sample. If the HPV test was conducted from a vaginal swab sample, a return visit is required for a clinician-taken (i.e. by a cervical sample taker) cervical LBC sample with speculum examination.

†Possible or definite high-grade cytology includes ASC-H, HSIL, SCC, atypical glandular cells, adenocarcinoma and AIS

Figure 5. HPV testing for females who are asymptomatic in New Zealand. Adapted from Clinical Practice Guidelines for Cervical Screening in Aotearoa New Zealand, 2023.25

ASC-US = atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; ASC-H = atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance cannot exclude HSIL; HSIL = high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; LSIL = low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; SCC = squamous cell carcinoma; AIS = adenocarcinoma in situ

Invalid/unsatisfactory tests or samples

HPV test invalid or unsuitable for analysis: repeat the test when practically possible.25 If the HPV test was initially conducted on a LBC sample and cytology has been reported, a vaginal swab sample can be used for the repeat HPV test.25

Unsatisfactory cytology sample: recall for repeat cytology in 6 – 12 weeks.25 If the reason for the unsatisfactory sample has been noted, this should be corrected where possible before taking the repeat LBC sample.25 Refer patients with HPV Type Other detected for colposcopy after two consecutive reports of unsatisfactory cytology.25

HPV Not detected

Place a recall to return for cervical screening in five years, or three years if immune deficient.25 The risk of a high-grade abnormality and cervical cancer for at least five years is very low in people who do not have HPV detected.25

Change in practice: A repeat HPV test in one year is not needed after the first ever cervical screening test if HPV is not detected.

HPV Detected Type 16/18

Refer patients with HPV Type 16 or 18 detected directly for colposcopy.25 If the HPV test was performed on a LBC sample, cytology will be reported automatically.25 If there is high suspicion of cancer based on cytology results, annotate this on the referral and mark the referral as urgent.25 If atypical endometrial cells are detected on cytology, further investigations are required; refer to local HealthPathways or discuss with/refer the patient to gynaecology.25 If the HPV test was performed from a vaginal swab, a LBC sample will be taken at the time of colposcopy.25

HPV Detected Type Other

If HPV Type Other is detected, management depends on cytology results (see below). If the HPV test was initially performed from a vaginal swab, a return visit is required for a LBC sample to be taken by a clinician (i.e. by a cervical sample taker) during a speculum examination.25 If the HPV test was initially performed on a cervical LBC sample, cytology will automatically be reported, and a return visit is not required.25

Reminder: If HPV of any type is detected in a person aged 70 – 74 years who is undergoing exit testing, they should be referred directly for colposcopy.25 If a person is immune deficient and has HPV detected (any type), they should also be referred directly for colposcopy.25 Where possible this should be informed by cytology results, but referral for colposcopy should not be delayed.

Atypical endometrial cells detected on cytology

Further investigation is required when atypical endometrial cells are detected on cytology, e.g. with ultrasound, pipelle biopsy; refer to local HealthPathways or discuss with/refer the patient to gynaecology.25 Colposcopy referral is not usually indicated, unless there is a co-existing reason for the patient to require colposcopy, e.g. immune deficient, cytology also shows high-grade lesions.25

Normal or low-grade changes (ASC-US, LSIL) detected on cytology

Place a recall for the patient to return in 12 months for a repeat HPV test; manage according to the HPV test result:25

- HPV Not detected – return to regular cervical screening interval

- HPV (any type) detected and immune deficient – refer for colposcopy

- HPV Type 16/18 detected – refer for colposcopy

- HPV Type Other detected – cytology informs management:

- High-grade changes – refer for colposcopy. If there is high suspicion of cancer based on cytology, annotate this on the referral and mark the referral as urgent (see: “Follow-up after colposcopy”). If atypical endometrial cells are reported, refer to local HealthPathways or discuss with/refer the patient to gynaecology.

- Normal or low-grade changes and the patient is aged ≥ 50 years – refer for colposcopy. If the patient is aged < 50 years – place a recall to return for a further HPV test in 12 months. If HPV is detected (any type), refer the patient directly for colposcopy (irrespective of cytology results if reported). If HPV is not detected, the patient can return to their regular cervical screening interval.

Follow-up after colposcopy

If the results from colposcopy are normal following referral for normal/low-grade changes on cytology, the patient will be referred back to primary care. Place a recall for a repeat HPV test at 12 months post-discharge from colposcopy. Manage according to the result:25

- HPV Not detected – return to regular cervical screening interval

- HPV Type 16 or 18 – refer for colposcopy

- HPV Type Other – cytology informs management:

- High-grade changes – re-refer for colposcopy. If there is high suspicion of cancer based on cytology, annotate this on the referral and mark the referral as urgent. If atypical endometrial cells are reported, refer to local HealthPathways or discuss with/refer the patient to gynaecology.

- Normal or low-grade changes – place a recall to repeat the HPV test in 12 months or if the patient is immune deficient, re-refer directly for colposcopy. If in 12 months’ time any HPV type is detected, re-refer for colposcopy (irrespective of cytology results if reported). If HPV is not detected, the patient can return to their regular cervical screening interval.

If the results from colposcopy show LSIL that has been histologically confirmed via biopsy, treatment is not required as these abnormalities indicate the presence of a viral infection that will resolve for the majority of people within two years.4, 25 Place a recall to repeat the HPV test at 12 months post-discharge from colposcopy and manage according to the results, as above.

If the results from colposcopy show HSIL or a glandular abnormality that has been histologically confirmed via biopsy, the patient will undergo treatment and management in secondary care, as there is an increased risk of cervical cancer if a high-grade or glandular abnormality is left untreated (see: “Follow-up after treatment for a high-grade cervical abnormality” and “Follow-up after treatment for adenocarcinoma in situ”).25

Follow-up after treatment for a high-grade cervical abnormality

People who have undergone treatment for a high-grade cervical abnormality are at higher risk of recurrence and invasive cervical cancer for 10 – 25 years.25 Once a patient has successfully completed treatment for HSIL, they will be referred back to primary care for a test of cure, which involves HPV and cytology testing.25 A test of cure has a high negative predictive value at detecting people who are at risk of recurrence.25

Recall patients at 6 and 18 months post-treatment for both HPV and cytology testing (‘co-tests’).25 If both tests are negative/normal on both occasions, the patient has successfully completed a test of cure and they can return to their regular cervical screening interval.25

If HPV is detected (irrespective of cytology results) at 6 or 18 months, or if HPV is not detected, but cytology results show possible/definite high-grade, refer the patient for colposcopy.25 If a patient does not have HPV detected but has two consecutive low-grade cytology results, they should also be referred for colposcopy.25 Recall the patient annually for repeat HPV and cytology testing until two consecutive negative/normal co-tests are taken 12 months apart; routine interval screening can then re-commence.25

For further information on the test of cure following treatment for HSIL, see: www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/assets/Our-health-system/Screening/HPV-Primary-Screening/clinical_practice_guidelines_final_version_1.1.pdf#page=56

Follow-up after treatment for adenocarcinoma in situ

Patients who have undergone complete excision (with adequate margins) for adenocarcinoma in situ that was HPV positive should have their initial follow-up appointment in colposcopy clinic at six months where the first co-test for a test of cure will occur.25 If both results are negative/normal, the second co-test will occur in primary care; place a recall for repeat HPV and cytology testing in 12 months post-discharge from colposcopy.25 If both tests are negative/normal, the test of cure has been completed and the patient can return to their regular cervical screening interval.25 If HPV is detected or cytology is abnormal, the patient should be re-referred for colposcopic assessment.25

Patients who have undergone complete excision for adenocarcinoma in situ that was HPV negative or HPV status unknown require annual co-tests indefinitely; place a recall for annual HPV and cytology testing.25

For information on the follow-up and surveillance of a patient after curative-intent treatment for cervical cancer, see: bpac.org.nz/2023/gynaecological-cancers.aspx

There is a B-QuiCK summary available for this topic

There is a B-QuiCK summary available for this topic