Published: 30th May, 2025

Key practice points

- Gout management in New Zealand is suboptimal. Initiation of urate-lowering treatment is often delayed, and once begun, many patients continue to have serum urate concentrations above recommended levels for urate crystal dissolution.

- Significant inequities exist for Māori and Pacific peoples with gout, e.g. undertreatment, greater disease burden, increased hospitalisation

- Gout can be diagnosed based on characteristic symptoms (e.g. joint involvement with pain/swelling/erythema), in the context of the patient’s history, with supporting evidence of elevated serum urate levels at a time other than during an acute attack

- Elevated serum urate levels alone are not diagnostic of gout, but may inform lifestyle changes (if relevant) and subsequent follow-up testing

- Treat gout flares with a NSAID, prednisone or low-dose colchicine; all are equally effective, so choice is based on individual factors

- Discuss urate-lowering treatment with all patients with gout at their first presentation (even if it is not prescribed), and encourage regular and consistent use when indicated; lifestyle changes are important but alone are insufficient to prevent future gout flares from occurring

- Titrate urate-lowering medicine doses until the patient achieves a serum urate level below 0.36 mmol/L; a target below 0.30 mmol/L is recommended for those with features of severe disease, e.g. tophi

- Allopurinol (fully funded) is the first-line urate-lowering medicine. Start at a low dose (renal function-dependent) and slowly up-titrate to reduce the risk of adverse effects.

- Regular serum urate testing should occur during up-titration (e.g. every four weeks), and then at least every 6 – 12 months once the target has been achieved

- Probenecid (fully funded) and febuxostat (funded with Special Authority approval) are alternatives for patients who find allopurinol ineffective or intolerable. Probenecid can also be used in combination with allopurinol or febuxostat, if required.

- Adherence is key for patients taking urate-lowering treatment; acknowledge that this can be challenging, but that daily use can prevent flares. Comparing past and present serum urate measurements can demonstrate progress. Discuss other strategies to encourage self-management, e.g. avoiding known triggers, healthy lifestyle changes, weight loss.

- Patients with gout require ongoing management of cardiovascular risk and monitoring for associated co-morbidities, e.g. chronic kidney disease and diabetes

Numerous interacting factors influence the long-term success of gout care, including patient-, clinician- and system-level barriers. Proactively identifying and addressing barriers within the control of primary care is essential to improving patient outcomes, as is a collaborative approach to care by all members of the primary care team.

For further information, see: “Peer group discussion: improving gout care”

This is a revision of a previously published article. What’s new for this update:

- A general article revision and consolidation of the previous two-part article series. Information on barriers to successful care has been shifted to a peer group discussion.

- Update of statistics, including 2024 New Zealand pharmaceutical dispensing data

- Further discussion on the optimal timing of urate-lowering treatment initiation

Gout is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis.1 It is associated with monosodium urate crystals accumulating in joint fluid, cartilage, bones, tendons and other tissues.1 Long-term hyperuricaemia is a prerequisite for crystal deposition and gout development, but not all people with hyperuricaemia develop gout.1

Urate is produced via the metabolism of dietary and endogenous purines.1 When urate levels in the blood reach saturation point, monosodium urate crystals can form; the intermittent inflammatory response to these crystals results in gout flares which are characterised by painful, red, hot, swollen joints.1 This most commonly occurs at the first metatarsophalangeal joint, but also occurs at other joints, e.g. knee, foot, ankle, wrist, hand, elbow. Over time, the duration and frequency of these flares may increase, resulting in chronic gouty arthritis and subcutaneous deposits of crystals, referred to as tophi, both of which can lead to the destruction of joints and musculoskeletal disability.1

Genetics and declining renal function primarily drive gout development – not diet

Once labelled the “disease of kings” due to its perceived association with food and alcohol overconsumption, diet is now recognised as a less significant risk factor for gout development. However, dietary factors can still be an important trigger of flares.1, 2 In most people, chronic hyperuricaemia and gout progression are driven primarily by genetic predisposition and declining renal function.2, 3 Detecting chronic kidney disease (CKD) early and preserving renal function is an important gout-prevention strategy.

Read more about gout genetics

A total of 377 genetic regions (loci) associated with gout have been identified to date.3 Genetic variants can contribute to gout development through numerous pathways, such as increasing urate production, reducing urate excretion or priming the immune system’s inflammatory response to urate crystals.3 The SLC2A9 gene, which encodes the fructose/urate co-transporter GLUT9, has been implicated in the greater number of Māori and Pacific peoples living with gout (see: “The burden of gout is more severe among Māori and Pacific peoples”).4 GLUT9 normally regulates urate reabsorption and excretion in the kidneys, helping to maintain urate balance. However, specific variants found at an elevated frequency among Māori and Pacific peoples enhance urate reabsorption, leading to hyperuricaemia and increased risk of gout development.

In addition to genetics, other hyperuricaemia/gout risk factors include:1, 5, 6

- Older age

- Male sex

- Obesity

- Cardio-metabolic co-morbidities, particularly CKD, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia

- Use of medicines that influence urate production, reabsorption or excretion, e.g. diuretics or low-dose aspirin (see: “The appropriate selection and use of cardiovascular medicines”)

- Dietary factors that increase exposure to purines, such as excessive consumption of red meat, seafood (kaimoana), beer, spirits, sucrose or fructose-sweetened drinks

The consequences of poorly-controlled gout are often overlooked

Gout can be an intensely painful condition that prevents people from working, performing daily activities and participating in their communities. People with gout will also often have co-morbidities, including hypertension and cardiovascular disease (CVD), CKD and diabetes.1 The relationship between co-morbidities and gout is complex; some occur independently, some predispose people to hyperuricaemia and gout, while others develop as a consequence of gout.1 In New Zealand, at least 40% of people with gout have diabetes and/or CVD.7 People with gout are also more likely to die at a younger age due to CVD or renal complications.8, 9

Despite these consequences, many people believe that gout is only treated with short-term analgesics for flares, or that nothing can be done at all.10 An over-reliance on acute treatments (e.g. NSAIDs, colchicine) also increases risk for people with gout, including severe gastrointestinal complications (e.g. gastroduodenal ulcers and bleeding, paralytic ileus), kidney damage and cardiovascular events.

Urate-lowering treatment improves long-term health outcomes

Unlike many other chronic conditions, gout can usually be successfully managed with pharmacological treatment, education and regular follow up. Lowering serum urate levels in patients with gout dissolves monosodium urate crystals and prevents further formation, reducing the risk of flares.11 This in turn limits the risk of tophaceous gout progression and progressive joint damage, as well as preserving physical function and improving quality of life.11

The management of CVD and renal co-morbidities is essential in patients with gout. Further investigation is required to establish the direct effect of urate-lowering treatment on cardiovascular/renal complications.

Read the evidence

- A 2017 meta-analysis (N = 1,211) found that in patients with hyperuricaemia and CKD, urate-lowering treatment slowed renal function decline, limited proteinuria and reduced the relative risk of cardiovascular events or renal failure by over 50%12

- A 2020 meta-analysis (N = 6,458) found that urate-lowering treatment did not significantly reduce the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events, kidney failure or all-cause mortality.13 However, this analysis encompassed 28 trials with different patient characteristics; 11 involved patients with hyperuricaemia or gout, one included those with normal serum urate, and the rest did not distinguish baseline serum urate status.

- A 2020 retrospective cohort study (N = 4,072) of patients with gout found that urate-lowering treatment reduced the relative risks of coronary artery disease and stroke by ~30% compared with no treatment.14 A dose-dependent effect was also identified.

- A large 2022 New Zealand cohort study (N = 31,907) demonstrated that, among males with gout and no history of CVD, regular urate-lowering medicine dispensing and treatment of serum urate to target levels was associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular events.15 This association was not observed for females.

The burden of gout is more severe among Māori and Pacific peoples

Gout has become more common in New Zealand over time.16 A HQSC report demonstrated that in 2019 approximately 6% of adults aged over 20 years had gout, compared with 4.5% in 2012.16 Gout prevalence increased with age and was more common among males.16 Notable ethnic disparities were also identified, including:16–18

- The prevalence of gout was higher in Māori (two-fold) and Pacific peoples (three-fold) compared to non-Māori, non-Pacific people. Notably, half of Pacific males aged 65 years or over were estimated to have gout.

- Māori and Pacific peoples were more likely to have an earlier onset of gout, with increased severity, tophaceous gout and accelerated joint damage, along with higher rates of co-morbidities.

- NSAID prescribing for gout was more common among Māori and Pacific peoples. They were also more likely to start preventative treatment (i.e. urate-lowering treatment) earlier than non-Māori, non-Pacific people, but were less likely to return for follow-up and repeat prescriptions. This indicates poorer gout management focused on temporary relief from symptoms associated with recurrent flares, rather than long-term prevention of urate crystal deposition or joint damage. Chronic NSAID use for gout causes harm, e.g. increasing the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, kidney damage and cardiovascular events.

- Māori and Pacific peoples were substantially more likely to be hospitalised with a primary diagnosis of gout compared with non-Māori, non-Pacific people. Many of these hospitalised patients did not receive a preventative gout medicine in the six months prior to admission.

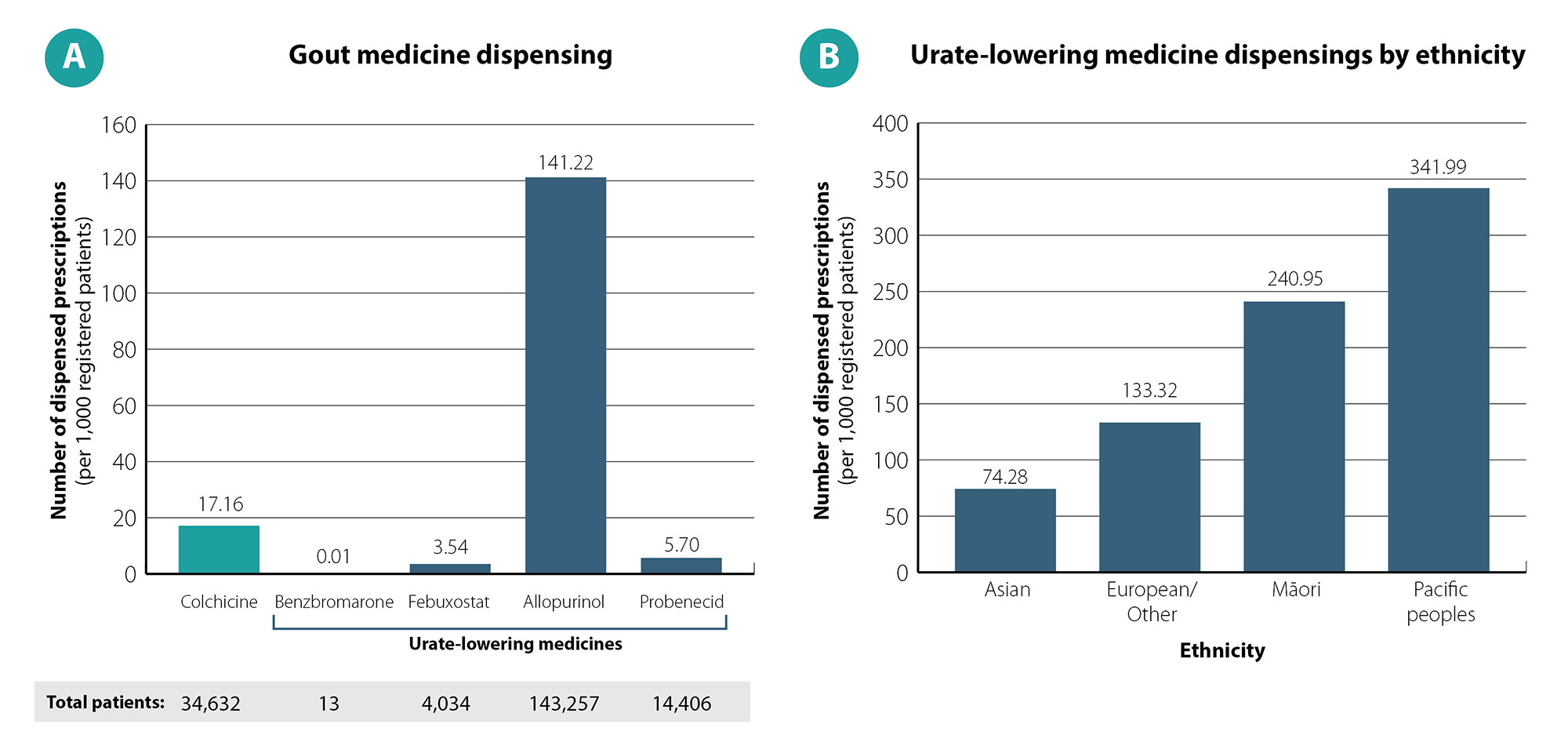

Analysis of more recent pharmaceutical dispensing data show that in 2024, approximately 160,000 patients in New Zealand were dispensed a urate-lowering medicine, most often allopurinol (141 patients per 1,000 registered patients; Figure 1A).19 Rates of urate-lowering medicine dispensing in 2024 were 1.8 times higher in Māori and 2.5 times higher in Pacific people compared with those of European/Other ethnicity (Figure 1B).19

Recognising gout and initiating effective treatment early in the clinical course is essential for addressing these disparities and the associated impact on other aspects of life, e.g. employment, ability to engage in daily activities, Hauora wellbeing.17, 18 To achieve equity, it has been estimated that over 10,000 additional Māori and over 8,500 additional Pacific peoples need to be initiated on preventative gout medicines each year.17, 18

Figure 1. Gout medicine dispensings among adults aged ≥ 20 years in New Zealand in 2024. Data on urate-lowering medicine dispensings in Part B includes patients dispensed at least one of benzbromarone, febuxostat, allopurinol or probenecid. Data obtained from Ministry of Health, Manatū Hauora, Pharmaceutical Claims Collection, 2025.19

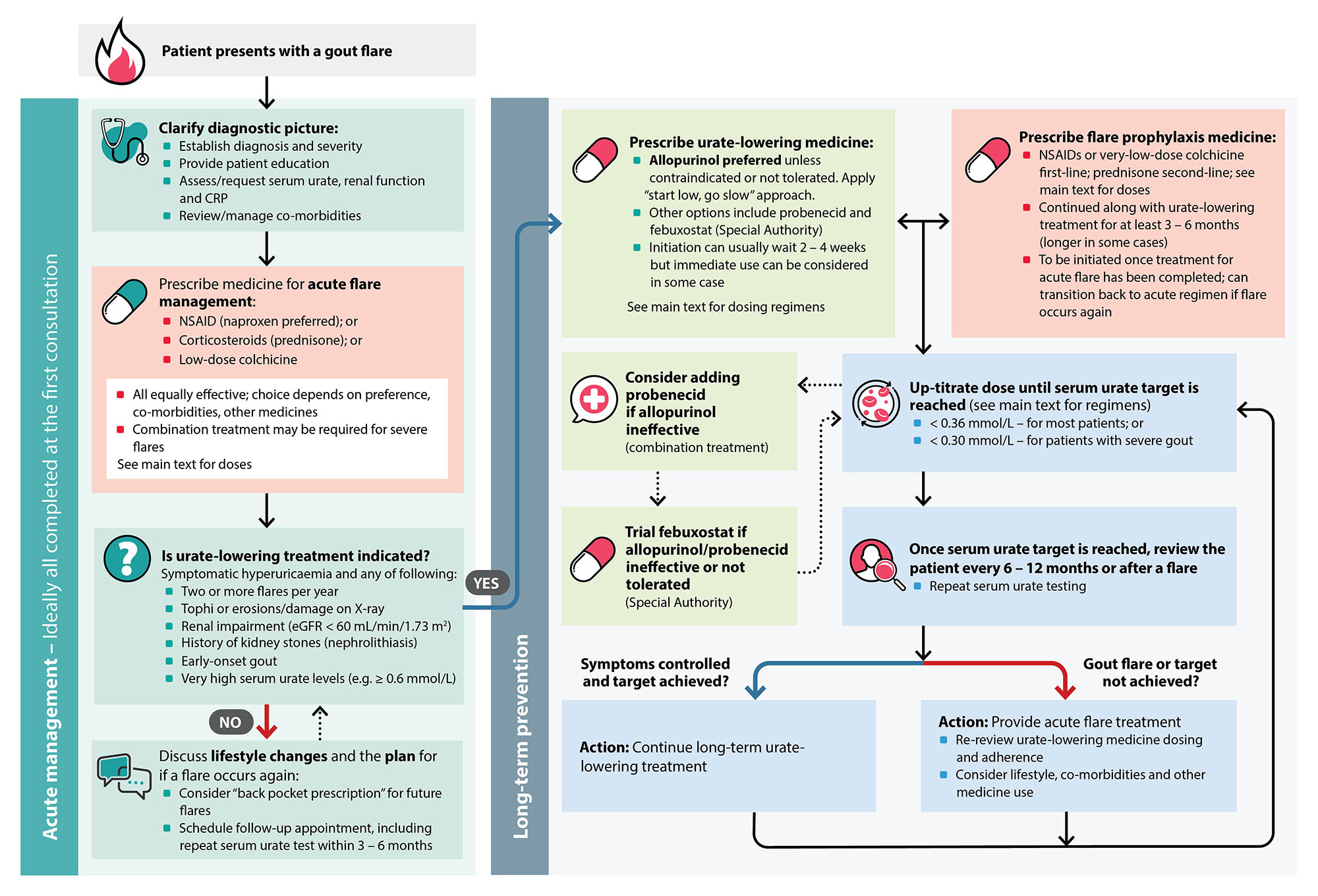

A diagnosis of gout can usually be made in primary care based on (Figure 2):

- Clinical presentation, e.g. joint involvement with characteristic pain/swelling/erythema, presence of any tophi or systemic symptoms

- History, e.g. onset, previous history of suspected flares or any elevated serum urate measurements

- Elevated serum urate levels

Also see: “Diagnosing gout using a scoring tool” for an example of a validated gout diagnosis tool.

Systemic symptoms (e.g. fever, fatigue) can occur due to the immune response associated with gout flares but may also indicate another diagnosis (see: “Differential diagnoses to consider”).

Serum urate levels during a gout flare will be within the normal range in up to 40% of cases.20 If levels are normal, testing should be repeated once the flare has subsided if gout is still strongly suspected.21 Requesting CRP along with a serum urate level can detect inflammation and assist in interpreting the validity of the urate level.

Best Practice Tip: Request a renal function test at the same time as the serum urate (and CRP) to allow for prompt urate-lowering treatment initiation, should a diagnosis of gout be confirmed. Also assess for relevant co-morbidities as this may influence medicine selection and the approach to long-term management.

The gold-standard for diagnosing gout is identification of intracellular monosodium urate crystals with polarising light microscopy in aspirated fluid from the affected joint.22 However, joint aspiration is rarely necessary in practice unless there is a high suspicion of another cause, e.g. septic arthritis.

Differential diagnoses to consider

Septic arthritis should be considered in patients with monoarticular joint pain, with erythema, warmth and joint immobility; systemic symptoms are present in around half of cases, which may help distinguish it from gout (where fever is much less common).23 Gout can sometimes occur concurrently in a patient with septic arthritis. Septic arthritis most commonly affects the knee, followed by the hip, shoulder, ankle and wrist.23 Patients are often older (e.g. aged ≥ 80 years) and have an underlying condition affecting the joint (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis); concurrent treatment with an immunosuppressive medicine, including prednisone, increases the risk of infection.23 Serum markers can vary widely and are not diagnostic, but patients with septic arthritis will often have an elevated white blood cell count and CRP level.23 Request acute orthopaedic assessment if septic arthritis is suspected. Joint aspiration for laboratory analysis may ultimately be required, as it can identify urate crystals, and Gram stain or culture can confirm/exclude the presence of infection; however, these investigations can be performed in secondary care (do not delay referral).23

Calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD) disease (formerly known as pseudogout) is an inflammatory arthritis caused by accumulation of calcium pyrophosphate crystals.24 CPPD prevalence is poorly understood and New Zealand data are not available; international studies estimate it affects 7 – 14% of European adults aged 60 years and 50% of those aged ≥ 80 years.24 Previous joint damage and older age are strong risk factors for CPPD (it is rare in people aged < 60 years).24 Patients with CPPD often have systemic symptoms, including fever and chills, and elevated inflammatory markers, which can make it difficult to distinguish from infection.24 Where there is clinical uncertainty, CPPD can be differentiated from gout and septic arthritis by requesting laboratory analysis of aspirated joint fluid.24 Radiography can also be used to support a diagnosis of acute calcium pyrophosphate crystal arthritis in joints that are unable to be aspirated.24 Unlike in gout, there are no medicines that can dissolve calcium pyrophosphate crystals, so management focuses on symptom relief.

Further information on diagnosing and managing calcium pyrophosphate crystal arthritis is available from: bpac.org.nz/bpj/2013/october/cppd.aspx (published in 2013; some information may no longer be current)

Figure 2. An overview of gout management in primary care.8, 25, 34

Diagnosing gout using a scoring tool

Various gout scoring tools have been developed but most are intended to support classification for clinical research.11, 22 Table 1 provides an example of a scoring system for assessing the likelihood of gout in a primary care setting.25 A score of eight or more is associated with a > 80% likelihood of gout.11 A score of four or less rules out gout in most patients and an alternative diagnosis should be considered.11

Table 1. Clinical score for the diagnosis of gout, adapted from Janssens et al. (2010).25

| Feature |

Clinical score |

| Serum urate > 0.35 mmol/L |

3.5 |

| First metatarsophalangeal joint involvement |

2.5 |

| Male sex |

2 |

| Previous reported flare |

2 |

| Hypertension or ≥ 1 cardiovascular disease* |

1.5 |

| Joint erythema |

1 |

| Onset within one day |

0.5 |

Score (maximum 13)

A score ≤4 usually rules out gout.

The higher the score, the greater the likelihood of gout. |

|

* Angina, myocardial infarction, heart failure, cerebrovascular event, transient ischaemic attack or peripheral vascular disease

Patients with gout usually initially present due to a painful flare, which will be the treatment priority. In addition to acute medicine use (see: “Prescribe a NSAID, corticosteroid or colchicine to treat gout flares”), encourage rest and elevation of the affected joint, adequate hydration, and some patients may find an ice pack beneficial.8, 26

The intensity of pain usually peaks within 24 hours, and flares often continue for 7 – 10 days if left untreated (complete resolution may take longer in some patients).27 Pharmacological intervention can significantly reduce pain intensity and flare duration, e.g. resolution within a few days.

Prescribe a NSAID, corticosteroid or colchicine to treat gout flares

There are several options for the acute treatment of gout flares, depending on specific patient characteristics (Figure 2 and Table 2). There is insufficient evidence to directly compare the efficacy of medicines for gout flares; all are considered first line. Medicine selection is therefore based on:8, 21, 26

- Renal function, e.g. prednisone may be preferred in a patient with reduced renal function, especially eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2

- Co-morbidities and concurrent medicine use, e.g. those that interact with colchicine; see: “Particular care is required with colchicine”

- Severity of the flare, e.g. combination treatment (NSAID or corticosteroid with colchicine), may be required if multiple joints are involved8

- Patient preference

Community pharmacists: be alert for persistent over-the-counter (OTC) NSAID use. Some patients self-manage gout flares by purchasing OTC NSAIDs (e.g. diclofenac) and do not consider long-term prevention. If you identify that a patient is persistently enquiring about NSAIDs for this purpose, suggest they see their primary care clinician regarding urate-lowering treatments.

Community pharmacists: be alert for persistent over-the-counter (OTC) NSAID use. Some patients self-manage gout flares by purchasing OTC NSAIDs (e.g. diclofenac) and do not consider long-term prevention. If you identify that a patient is persistently enquiring about NSAIDs for this purpose, suggest they see their primary care clinician regarding urate-lowering treatments.

Table 2. Treatment options for an acute gout flare.8, 28

Medicine |

Dose |

Notes |

NSAIDs – Naproxen preferred |

- 750 mg initially, followed by 500 mg eight hours later, then 250 mg every eight hours until the flare has settled

|

- Avoid if eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2

- Consider adding a proton pump inhibitor

- Consider celecoxib if intolerant to naproxen (unapproved indication)

|

Prednisone |

- 20 – 40 mg, once daily, for five days or until the flare has settled

|

- Tapering the dose over 10 – 14 days can reduce the likelihood of a rebound flare, but is not always necessary with a short course

|

Colchicine |

- Low-dose regimen*: 1 mg immediately, followed by 500 micrograms after one hour; maximum dose 1.5 mg per course

- If eGFR 10 – 50 mL/min/1.73 m2, reduce the initial dose by half (i.e. 500 micrograms); do not exceed 1.5 mg over three days

|

- Do not repeat acute course within three days

- Do not commence prophylaxis (very-low-dose colchicine) until 12 hours or more after the acute dose is taken

- Ideally avoid, or use with caution, in frail patients, those who weigh < 50 kg, or patients with hepatic or renal impairment (eGFR 10 – 50 mL/min/1.73 m2)

- Contraindicated in patients with an eGFR < 10 mL/min/1.73 m2

|

Corticosteroid

(triamcinolone acetonide) |

- Intra-articular injection, 2.5 – 40 mg

|

- May be considered in patients where the oral route is problematic and if only one or two joints are affected

- Dose determined by the size of the affected joint

|

* This regimen is based on a trial in which patients received treatment within 12 hours of onset of the flare;29 efficacy may therefore be reduced if started later

Provide a “back pocket prescription” for managing future events

Patients with gout require ready access to medicines for managing flares until they achieve long-term symptom control with urate-lowering treatment.26 An extra quantity of acute gout medicine can be prescribed for this purpose; emphasise to patients that medicines should be taken promptly for acute flares and then stopped when the flare has settled (unlike urate-lowering treatments which are taken every day). Medicines should be stored in a secure and safe location, especially colchicine as relatively small overdoses can be fatal (see: “Particular care is required with colchicine”).

Particular care is required with colchicine

Colchicine is useful in gout management but it has a narrow therapeutic index, meaning the range between therapeutic and toxic effects is small and can overlap.30 Colchicine is very toxic in overdose and there is no reversal agent; doses of > 0.5 – 0.8 mg/kg are generally fatal, and deaths have occurred with even lower doses.30

Three phases of colchicine poisoning include:30

- Gastrointestinal phase (10 – 24 hours) – including abdominal pain, nausea/vomiting and diarrhoea

- Multiorgan phase (2 – 7 days) – can include a wide range of serious adverse effects including paralytic ileus, myopathy, myocardial toxicity and severe cardiovascular dysfunction, respiratory failure and blood dyscrasias

- Recovery phase in those who survive (within a few weeks)

Colchicine is contraindicated in patients with severe renal or hepatic impairment, significant gastrointestinal or cardiac conditions or pre-existing blood dyscrasias.28 The adverse effects of colchicine may also be exacerbated by medicine interactions.28, 30 Caution is advised when prescribing colchicine to patients who are taking medicines that inhibit the CYP3A4 enzyme and/or P-glycoprotein, e.g. erythromycin, clarithromycin and verapamil.28, 30 Colchicine plasma concentrations can be doubled by concomitant CYP3A4 inhibitor use and quadrupled by concomitant P-glycoprotein inhibitor use.28 Neuromyopathy is a rare complication, and there are reports of rhabdomyolysis in patients taking statins.31

Tips for safer colchicine use:8, 26, 28

- Prescribe the lowest effective dose and provide clear instructions on how and when to take it

- Advise patients to stop taking colchicine and seek medical attention if they experience nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea or abdominal pain

- Limit prescriptions to the anticipated number of tablets required for managing an acute attack of gout. For prophylactic use consider monthly dispensing.

- Pharmacists should consider dispensing with a child-resistant closure and advise patients to store colchicine out of sight and reach of children

If the patient is taking very-low-dose colchicine for flare prophylaxis, this must be stopped during low-dose colchicine treatment for an acute flare, i.e. ensure they do not take both regimens at the same time.

If the patient is taking very-low-dose colchicine for flare prophylaxis, this must be stopped during low-dose colchicine treatment for an acute flare, i.e. ensure they do not take both regimens at the same time.

For further information on safer colchicine prescribing, see: bpac.org.nz/bpj/2014/september/safer-prescribing.aspx (published in 2014; some information may no longer be current)

The NZF interactions checker provides details on medicine interactions and their clinical significance, available from: www.nzf.org.nz

Urate-lowering treatment should be discussed once a gout diagnosis has been made, even if it is not prescribed straight away.8, 26 This includes patients currently experiencing a gout flare as some may not return for a follow-up consultation.

The discussion should cover:

- How urate-lowering treatment works

- The benefits, e.g. less likely to require treatment for gout flares, fewer adverse effects due to reduced exposure to NSAIDs.11 Explain the risks of treatment, but that in most cases the benefits outweigh these (see: “Allopurinol is generally well-tolerated but caution patients about rare severe reactions”).

- The importance of adhering to regular daily treatment, the need to titrate the dose over time depending on serum urate levels and a commitment to lifelong use

- That urate-lowering treatment should be continued during future flares (assuming they have been adherent in the weeks and months leading up to the event). If urate-lowering treatment is stopped, even after years of being symptom-free, most patients will eventually experience a return of flares.26

- Any concerns the patient has about long-term treatment, and barriers that may prevent this occurring, e.g. medicine access

Patients experiencing intense pain due to their flare may not recall all this discussion, so it is good practice to check at the next visit what has been heard and understood.

Urate-lowering medicines are not indicated in people with hyperuricaemia who are asymptomatic.26

Urate-lowering medicines are not indicated in people with hyperuricaemia who are asymptomatic.26

Aim to initiate urate-lowering treatment early when indicated

Start urate-lowering treatment in patients with symptomatic hyperuricaemia and any of the following:8, 11, 26

- Two or more flares per year (including if self-managed)

- Tophi or erosions/damage on X-ray

- Renal impairment (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2)

- History of kidney stones (nephrolithiasis)

- Early-onset gout, e.g. aged < 40 years; the average age of onset is significantly lower for Māori (39 years) and Pacific peoples (33.5 years) compared to New Zealand Europeans (46.5 years)32

- Very high serum urate levels, e.g. ≥ 0.6 mmol/L

Initiation of urate-lowering treatment can be considered during a flare in some cases, but caution is required

The optimal timing of urate-lowering treatment initiation is debated.33, 34 Conventionally, initiation of urate-lowering treatment is delayed until the pain of a flare has resolved,34 the rationale being that remodelling of urate crystals causes dispersion of microscopic tophi during the initiation phase of treatment, which may worsen pain. However, a 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs concluded that there is no evidence for harm or for benefit of initiating urate-lowering treatment during a gout flare (based on moderate-to-low quality evidence); it does not significantly impact the duration or severity of the flare in patients without renal impairment or tophi.34

Current international guidelines offer conflicting recommendations. British Society for Rheumatology 2017 guidelines and NICE 2022 recommend that urate-lowering treatment is best delayed until the gout flare has resolved,8, 21 whereas 2020 American College of Rheumatology guidelines conditionally recommend starting treatment during a flare rather than waiting for it to resolve.26

An individualised approach is best. In most patients, it is reasonable to delay urate-lowering treatment initiation (e.g. for two to four weeks) for several practical reasons:

- Urate-lowering treatment is a long-term commitment, and there is no compelling evidence that immediate initiation improves adherence

- Serum urate measurements can be within the “normal” range during flares; immediate use of urate-lowering treatment prevents the establishment of an accurate baseline level

- Initiation concurrently with acute flare treatments can make it difficult to distinguish which medicine is responsible for adverse effects

- Delaying initiation presents an opportunity to schedule a follow-up appointment where more time can be taken to assess co-morbidities and continue education and discussion

However, immediately initiating urate-lowering treatment during a flare is still reasonable for some patients, such as those who:

- Have early-stage gout, i.e. only had one or two flares

- Express a preference for starting long-term prevention as early as possible

- Are unlikely to return for a subsequent appointment for initiation

- Do not have tophi, renal impairment or multiple joints involved

Best Practice Tip: If allopurinol is initiated during a flare, start at a low dose and ensure the patient understands that it must be continued after the flare resolves, even when other acute medicines are ceased. Medicines used for the acute treatment of flares can be continued at lower doses for flare prophylaxis. If allopurinol is not immediately initiated (but is indicated), ensure that either a prescription is written for the patient to pick up once the flare resolves, or that a follow-up appointment is scheduled. This appointment will allow time to assess for cardiovascular and metabolic co-morbidities, which are often present or will become so in the future (and therefore preventative management can be started).

Urate-lowering treatment is often delayed and suboptimal

Numerous studies show that initiation of urate-lowering treatment is often delayed well beyond the point when it is indicated. The causes for this are multifactorial, including both clinician- and patient-level barriers. Once treatment is initiated, it is important to continue to educate and motivate patients to take responsibility for their health, and to identify/address any barriers that might influence long-term adherence.

In New Zealand, urate-lowering treatment is initiated earlier in Māori and Pacific peoples compared to non-Māori, non-Pacific people (10 and 13 years earlier, on average, respectively).17, 18 However, given the more significant gout burden and hospitalisation risk among these groups it has been suggested preventative treatment should be initiated even earlier in many cases.17, 18

Once urate-lowering medicines are started, monitoring is also often suboptimal, resulting in many patients with serum urate concentrations above recommended levels for treating gout. An estimated 44% of patients with gout in New Zealand do not undergo laboratory serum urate testing within six months of urate-lowering treatment dispensing; although a proportion of these patients may be receiving point-of-care urate testing, which has become more prevalent over time.16

The goal of urate-lowering treatment is to reduce serum urate levels below the saturation point to dissolve urate crystals, thereby preventing future gout flares.8 Depending on the urate-lowering medicine, this is achieved through different mechanisms of action, including inhibiting urate production (xanthine oxidase inhibitors, e.g. allopurinol, febuxostat) or increasing renal urate excretion (uricosuric drugs, e.g. probenecid).11

The recommended serum urate levels are:21, 29

- < 0.36 mmol/L – for most patients; or

- < 0.30 mmol/L – for patients with severe gout, e.g. those with tophi, chronic gouty arthritis or frequent flares

There have not been any head-to-head trials comparing different serum urate thresholds, but post-hoc evidence suggests that both stringent thresholds (e.g. < 0.30 mmol/L) and lenient thresholds (e.g. < 0.42 mmol/L) reduce the risk of subsequent flares.35 The general target of < 0.36 mmol/L balances the efficacy of crystal dissolution against the risk of adverse effects with increasing urate-lowering treatment doses required. Patients consistently treated to a serum urate level of < 0.30 mmol/L can be switched to the less stringent target of < 0.36 mmol/L after several years of symptom-free treatment and resolution of tophi, if present.8

Test serum urate levels:20

- Prior to dose adjustment while urate-lowering treatment is being titrated, e.g. initially every four weeks

- Every six to 12 months for monitoring once targets have been achieved

Avoid testing serum urate levels during a flare for the purposes of monitoring the patient’s treatment response as levels may be lower than normal (i.e. request test once resolved).20

Best Practice Tip: Place a recall in the patient’s record to re-check their serum urate level after initiating urate-lowering treatment, after a dose adjustment and then at regular intervals to better support consistent long-term monitoring.

Flare prophylaxis is recommended when initiating urate-lowering treatment

During the first months of urate-lowering treatment the rapid decline in serum urate is thought to disrupt pre-formed monosodium urate crystals, making them more likely to provoke a local inflammatory response which can result in an acute flare of gout.8, 11

Prophylactic treatment should generally be provided for the first three to six months of urate-lowering treatment (Table 3).8, 26 Patients who are symptom-free at their three-month review and have had a substantial drop in serum urate levels may be able to stop prophylactic treatment.26 Prophylactic treatment can be required for longer than six months in patients with frequent ongoing flares or tophi (e.g. 12 months or more), but the risks of ongoing treatment (i.e. adverse effects of NSAIDs or colchicine) need to be weighed against the potential benefits.26 Further emphasis on optimising urate-lowering treatment and modifiable lifestyle factors may be required.

Gradual dose titration also reduces the risk of flares, compared to starting full doses. Discuss the increased risk of flares during initiation of urate-lowering treatment with patients and advise them to persist with use if a flare does occur.

Table 3. Treatment options for gout flare prophylaxis.8, 26, 28

Medicine |

Dose |

Additional notes |

Naproxen |

250 mg, twice daily |

- Consider adding a proton pump inhibitor

- Avoid if eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2

|

Colchicine

(unapproved indication) |

Very-low-dose regimen: 500 micrograms, twice daily

Reduce dose if required (see notes) |

- Reduce dose to 500 micrograms, once daily, or on alternate days, if not tolerated, e.g. diarrhoea develops, chronic kidney disease or concurrent use of CYP3A4/P-glycoprotein inhibitors (such as erythromycin, verapamil)

- Ideally avoid, or use with caution, in frail patients, those who weigh < 50 kg, or patients with hepatic or renal impairment (eGFR 10 – 50 mL/min/1.73 m2)

- Contraindicated in patients with an eGFR < 10 mL/min/1.73 m2

|

Prednisone |

5 mg, once daily |

- Second-line option if contraindications to NSAIDs or colchicine

- Taper slowly on withdrawal

- Monitor for corticosteroid-related adverse effects

|

Best Practice Tip: If a patient is receiving treatment for a gout flare with a NSAID or colchicine, continue the same medicine at a lower dose for prophylaxis once the flare has resolved. If a flare occurs during prophylactic treatment, stop the prophylactic dose and change to a regimen for acute treatment of a flare (see: “Prescribe a NSAID, corticosteroid or colchicine to treat gout flares”).

Blister packs simplify treatment for patients and encourage adherence

Multiple medicines are often required for the initial treatment of gout, including acute flare management and prophylaxis, and increasing doses of allopurinol or another urate-lowering medicine. This requires careful instruction to ensure that the patient takes the right dose of the right medicine at the right time. A potential solution for some patients is to have medicines dispensed in a blister pack, or to organise them in medicine boxes. Pharmacies usually charge an additional fee for blister pack dispensing, but funding may be available – check with your local PHO.

Allopurinol is a xanthine oxidase inhibitor that decreases urate production by inhibiting purine metabolism. It is the first-line urate-lowering medicine for patients with gout.8, 26

The starting dose of allopurinol is determined by the patient’s renal function

The dose of allopurinol required to reach serum urate targets varies between patients. Therefore, allopurinol is started at a low dose and slowly titrated upwards to minimise adverse effects, until the patient reaches their target serum urate level (Table 4).8, 28 Allopurinol can be safely used in patients who have reduced renal function, with a lower starting dose and slower titration. Dose reductions are not routinely required in patients with declining renal function who are already established on allopurinol.

Table 4. Allopurinol starting doses and dose titration determined by renal function.28

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) mL/min/1.73 m2 |

Initial dose of allopurinol |

Dose increase |

> 60 |

100 mg, daily |

Increase by 100 mg, every four weeks*, if tolerated, until the serum urate target is reached, or to a maximum of 900 mg, daily. Usual maintenance dose is 100 – 600 mg/day. |

30 – 60 |

50 mg, daily |

Increase by 50 mg, every four weeks, if tolerated, until the serum urate target is reached, or to a maximum of 900 mg, daily† |

< 30 |

50 mg, every second day |

* Some prescribers prefer a more rapid titration (e.g. every two weeks), but this needs to be balanced against the increased risk of adverse effects

† Many patients with renal dysfunction will be unable to tolerate the maximum dose of allopurinol; consider referral to, or discussion with, a rheumatologist if serum urate targets are unable to be achieved and an increase in dose is not tolerated, e.g. over 300 mg allopurinol daily

Dose titration is essential to achieve serum urate targets

Once allopurinol has been initiated, regular follow-up with serum urate testing is required while the dose is titrated upwards, until the serum urate target is reached. A standard 300 mg dose of allopurinol is often prescribed, but this is insufficient to achieve serum urate targets in 30 – 50% of patients with gout and normal renal function, and higher doses are required.29, 36 RCT and observational study evidence shows that treatment with up to 600 – 800 mg per day of allopurinol achieves a target serum urate level in 75 – 80% of patients.29 At each consultation, re-emphasise the importance of adherence and encourage healthy lifestyle changes (especially weight loss; see: “Supporting patients in the long term”).

Other urate-lowering medicines are available for patients who are unable to tolerate allopurinol or achieve their serum urate target with allopurinol alone (probenecid, febuxostat – see next sections). However, if flares are controlled and urate levels are only slightly above target, some patients may choose to persist with allopurinol alone, rather than taking an additional medicine.

Partnering with community pharmacies: Community pharmacists can have a supporting role in optimising allopurinol dosing with point-of-care urate testing and standing orders provided by general practitioners. This process can be highly effective in improving access and engagement (particularly for Māori and Pacific peoples), although various factors may impact implementation, e.g. funding barriers, processes to share patient records. For further information, see: goutguide.nz.

Allopurinol is generally well tolerated but caution patients about rare severe reactions

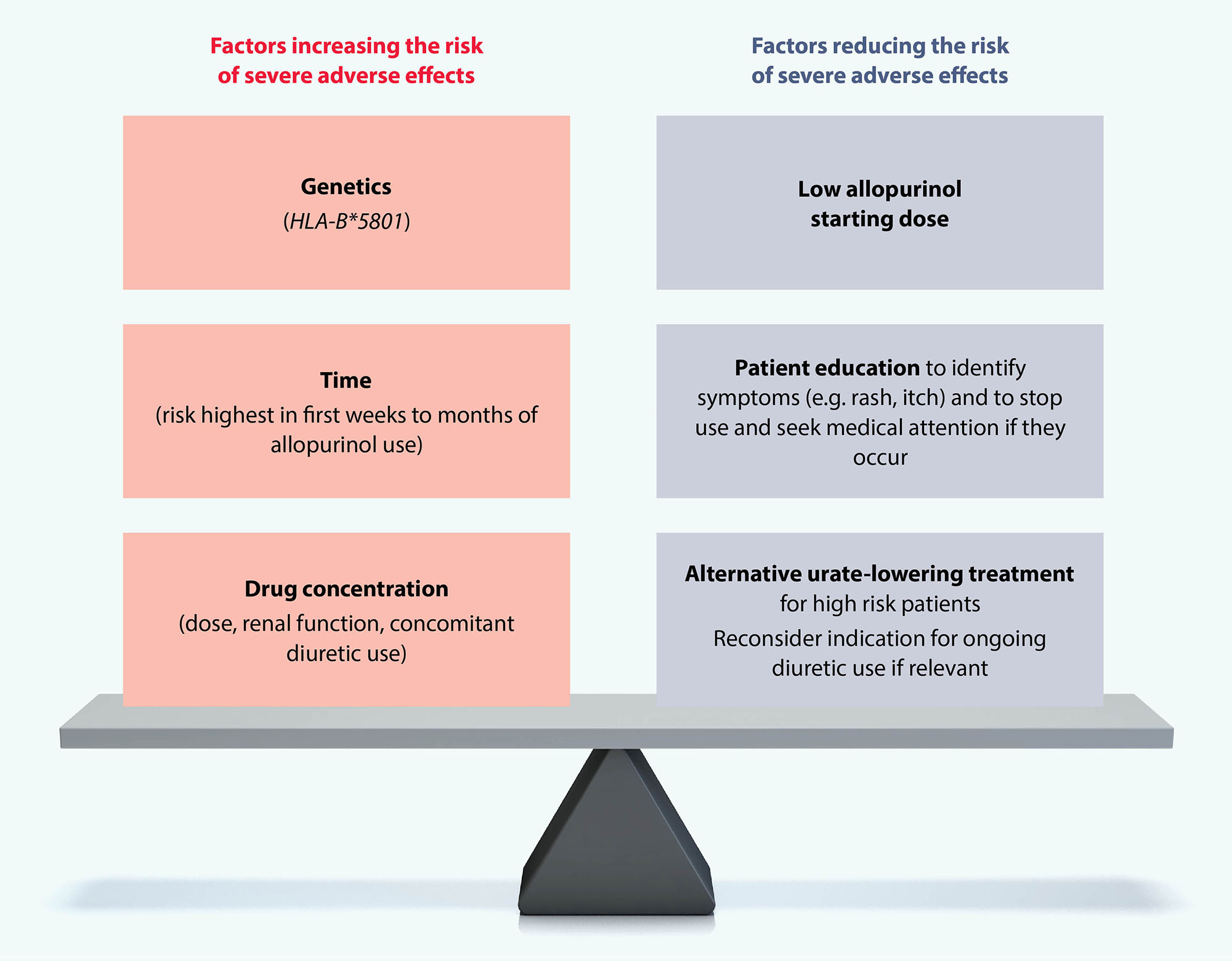

Allopurinol is generally well tolerated, although some patients will experience gastrointestinal symptoms.8, 28 Severe cutaneous adverse reactions are estimated to occur in 0.1 – 0.4% of patients taking allopurinol, including drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.37–39 Various factors influence the risk of these adverse events occurring (Figure 3).39

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS)

DRESS has a mortality rate ranging between 3 – 10%.37, 38 It is characterised by an erythematous, extensive desquamating rash, fever, eosinophilia, leukocytosis, hepatitis and renal failure.37–39 DRESS most often occurs in the first few weeks to months of initiating treatment with allopurinol.39 The risk of DRESS can be substantially reduced by introducing allopurinol at a low dose and slowly titrating upwards after tolerance has been established; this is particularly important in patients with impaired renal function.39 Patients should stop taking allopurinol and seek medical advice if they develop a rash or itch; an alternative urate-lowering medicine can be trialled.39

Consider checking patients of Han Chinese, Korean or Thai ancestry for the HLA-B*5801 allele before prescribing allopurinol.37–39 This variant is associated with a notable increase in DRESS risk, and is more common among people of these ethnicities (screening is not recommended in other ethnic groups). Avoid allopurinol in patients confirmed to have HLA-B*5801.8 It is recommended to discuss genetic testing with Genetic Health Service NZ or your local laboratory (www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/health-services-and-programmes/genetic-health-service-nz).

Consider checking patients of Han Chinese, Korean or Thai ancestry for the HLA-B*5801 allele before prescribing allopurinol.37–39 This variant is associated with a notable increase in DRESS risk, and is more common among people of these ethnicities (screening is not recommended in other ethnic groups). Avoid allopurinol in patients confirmed to have HLA-B*5801.8 It is recommended to discuss genetic testing with Genetic Health Service NZ or your local laboratory (www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/health-services-and-programmes/genetic-health-service-nz).

Figure 3. Risk factors for severe allopurinol-related adverse effects.39

Probenecid can be added to the urate-lowering regimen if the patient is unable to achieve their serum urate target despite taking a relatively high dose of allopurinol, e.g. 600 mg, daily.8, 29 However, first assess adherence to treatment, as non-adherence can account for insufficient treatment responses. Probenecid can also be prescribed as monotherapy to patients who are intolerant or resistant to allopurinol.8, 29

Probenecid dosing is titrated according to the patient’s serum urate concentration:28

- Initially, 250 mg, twice daily, for one week, then 500 mg, twice daily, with the dose increased by 500 mg every four weeks, to 1 g, twice daily (i.e. 2 g total per day), if required

The efficacy of probenecid reduces with declining renal function as its mechanism depends partly on its ability to block urate reabsorption;40 it should be avoided in patients with an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.8, 28 Probenecid is contraindicated in patients with nephrolithiasis.8 Common adverse effects are nausea and vomiting.28 Advise patients to drink adequate fluids (e.g. at least two litres per day), to prevent the formation of uric acid stones and to take the medicine with, or just after, a meal.28, 40 Sodium bicarbonate can also be considered for alkalising urine in patients with recurrent uric acid stones (see: “Reducing the risk of kidney stones”).

If treatment with allopurinol and/or probenecid is ineffective or cannot be tolerated, febuxostat (Special Authority required) is a second-line xanthine oxidase inhibitor.8, 29

The recommended dose of febuxostat for patients with gout is:28

- 80 mg, once daily, increased to 120 mg*, once daily, after two to four weeks if the serum urate is > 0.36 mmol/L

* The maximum daily dose of febuxostat for patients with mild hepatic impairment is 80 mg

Funded with Special Authority approval

Febuxostat is funded with Special Authority approval for patients with gout who have a serum urate level > 0.36 mmol/L and:28

- Have been treated with allopurinol at doses of at least 600 mg per day in addition to probenecid at doses up to 2 g per day or to a maximum tolerated dose; or

- Have intolerable adverse effects associated with allopurinol treatment requiring treatment discontinuation and have trialled probenecid at doses up to 2 g per day or to a maximum tolerated dose; or

- Have had optimal treatment with allopurinol, however, renal impairment means that probenecid cannot be added or is likely to be ineffective

Patients who have had previous Special Authority approval for benzbromarone are also eligible for Special Authority approval for febuxostat (see: “Benzbromarone to be discontinued”).

Key prescribing points for febuxostat

Renal impairment. Febuxostat can be used in patients with renal dysfunction as this is not a significant route of elimination.11 Probenecid should be avoided in patients with an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, therefore, febuxostat is the recommended choice in this patient group (if allopurinol is not tolerated or adequate), however caution is still advised due to a lack of safety data.8, 28

Hepatic impairment. Patients with mild hepatic impairment should not exceed a daily dose of 80 mg.28 There is no dose information available for patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment. Arrange baseline liver function testing, as abnormal results have been observed in 5% of patients taking febuxostat; repeat testing is recommended periodically thereafter based on clinical judgement.28

CVD risk. Caution is advised when considering prescribing febuxostat to patients with a history of CVD (particularly heart failure and coronary artery disease), however, this is not a contraindication.26, 28 Some previous studies suggested that febuxostat use is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular- and all-cause mortality compared with allopurinol.41 The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) therefore updated prescribing information with a boxed warning in 2019, advising that clinicians should discuss the elevated CVD risk with patients and inform them about symptoms to look out for, e.g. shortness of breath, chest pain.42 More recent studies, however, have not found an increase in the risk of all-cause mortality associated with febuxostat compared with allopurinol; one study even demonstrated a lower risk.43, 44 Ensure patients are aware of the evidence around CVD risk and febuxostat use as part of a shared decision-making discussion.26

Combination treatment. Probenecid can be added to the treatment regimen if the patient is unable to achieve the target serum urate level with febuxostat alone.8, 26 However, this combination is associated with a more rapid decline in serum urate and can trigger flares in some people; prophylactic management with either a NSAID or colchicine is essential when using it for at least the first six months.8, 26

The adverse effects of febuxostat

Adverse effects most often associated with febuxostat are diarrhoea, nausea, elevated liver enzymes (in rare cases leading to hepatotoxicity), oedema, headache and rash.28 Hypersensitivity reactions are rare, but most often occur in the first weeks of treatment, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, urticaria and anaphylaxis.28 It is unknown whether previous severe cutaneous adverse reactions to allopurinol increases the subsequent risk with febuxostat.8

There is a 16% increased relative risk of flares in patients taking febuxostat compared with allopurinol, making flare prophylaxis particularly important in the first months of treatment.8

Benzbromarone to be discontinued

Benzbromarone (Section 29) is no longer included as an option for long-term gout prevention as it is likely to be delisted from the Pharmaceutical Schedule, due to ongoing global supply issues.* 45 Most patients previously taking benzbromarone have now switched to a different treatment (in 2024, only 13 patients were dispensed this medicine).19 No new patients should be started on benzbromarone and any patients remaining on it should be changed to a different urate-lowering medicine as soon as possible.45 The Special Authority approval for febuxostat allows patients who were taking benzbromarone to access funded febuxostat treatment.45

* As of May, 2025, there is no date set for delisting – for up-to-date information, visit the Pharmac website

Acknowledge that taking a medicine every day for gout can be challenging. Ask about any concerns or barriers the patient may have to taking regular medicines. It can also be useful to discuss whether family members/whānau are taking allopurinol for gout and how well they are doing (especially if doing well). Regularly check in with the patient about how they are managing their gout medicines. Acknowledge that people can often forget to take medicines, and ask what might make it easier for them, e.g. blister packaging, setting themselves phone reminders.

Acknowledge that taking a medicine every day for gout can be challenging. Ask about any concerns or barriers the patient may have to taking regular medicines. It can also be useful to discuss whether family members/whānau are taking allopurinol for gout and how well they are doing (especially if doing well). Regularly check in with the patient about how they are managing their gout medicines. Acknowledge that people can often forget to take medicines, and ask what might make it easier for them, e.g. blister packaging, setting themselves phone reminders.

Once the patient achieves their serum urate target, continue to measure serum urate levels at least every 6 – 12 months (or after a flare) and make any necessary adjustments to the treatment regimen if the target level is not maintained. Titrating and identifying the optimal dose of a urate-lowering medicine can be challenging, and patients need to be supported and reassured throughout this process. Explain that it’s important to continue with treatment as urate levels return to previous levels within one week of stopping a urate-lowering medicine. If it is stopped for some time, it will need to be restarted at the initiating dose and prophylaxis taken to avoid a gout flare.

Once the patient achieves their serum urate target, continue to measure serum urate levels at least every 6 – 12 months (or after a flare) and make any necessary adjustments to the treatment regimen if the target level is not maintained. Titrating and identifying the optimal dose of a urate-lowering medicine can be challenging, and patients need to be supported and reassured throughout this process. Explain that it’s important to continue with treatment as urate levels return to previous levels within one week of stopping a urate-lowering medicine. If it is stopped for some time, it will need to be restarted at the initiating dose and prophylaxis taken to avoid a gout flare.

Best Practice Tip: Patients can be motivated to continue taking urate-lowering treatment if you compare current to past serum urate levels and highlight the reduced number of gout attacks to demonstrate progress.

Reiterate that although biological factors (e.g. CKD, genetics) are the main causes of gout, other modifiable factors such as diet can still trigger flares. Discussion points include:

Reiterate that although biological factors (e.g. CKD, genetics) are the main causes of gout, other modifiable factors such as diet can still trigger flares. Discussion points include:

- Eat regular meals – periods of fasting/starvation may trigger flares

- Avoid/limit foods if they trigger flares, e.g. red meat, seafood (kaimoana)

- Increase vegetable intake and switch to low-fat dairy products (e.g. skim milk) as part of a healthy diet to support weight loss (see below); this may reduce the risk of flares in some patients.

- Purine content in foods does not necessarily predict their effect on serum urate levels, as it depends on the type of purine and other nutritional components of the food. Purine-rich foods need only be avoided if they trigger flares; information on the purine content of foods is available online, e.g.: www.arthritis.org.nz.

- Limit alcohol and drinks high in fructose/sucrose

- Keep hydrated (see: “Reducing the risk of kidney stones”)

- Vitamin C supplementation is unnecessary – this was previously proposed to reduce serum urate, but this has since been disproven in people with gout8

By being aware of triggers, and taking urate-lowering medicines consistently, future flares can be prevented, and patients can feel more engaged in self-management. In some cases, patients will eventually be able to consume small portions of trigger foods without experiencing a flare.

Use motivational interviewing to encourage lifestyle changes including weight loss and regular exercise which can reduce serum urate levels, and therefore the risk of flares, along with other benefits for cardiovascular and diabetes co-morbidities. Medicines such as statins and antihypertensives may need to be added. N.B. Continuous, high-intensity exercise increases lactic acid levels, which in turn reduces uric acid excretion, therefore should be avoided in people with gout.

Use motivational interviewing to encourage lifestyle changes including weight loss and regular exercise which can reduce serum urate levels, and therefore the risk of flares, along with other benefits for cardiovascular and diabetes co-morbidities. Medicines such as statins and antihypertensives may need to be added. N.B. Continuous, high-intensity exercise increases lactic acid levels, which in turn reduces uric acid excretion, therefore should be avoided in people with gout.

Provide education and resources, e.g. a “Gout management plan” (see: goutguide.nz)

Provide education and resources, e.g. a “Gout management plan” (see: goutguide.nz)

Track any changes in clinically relevant biomarkers, e.g. at least an annual assessment of blood pressure, HbA1c and renal function

Track any changes in clinically relevant biomarkers, e.g. at least an annual assessment of blood pressure, HbA1c and renal function

The appropriate selection and use of cardiovascular medicines

For patients with gout and hypertension, losartan is the antihypertensive of choice as it has mild uricosuric (urate-excreting) properties.26, 46 In contrast, diuretics reduce urate excretion and therefore contribute to the onset and exacerbation of gout. Diuretic use also increases the risk of DRESS, so it is important to evaluate whether there remains an indication for ongoing use prior to allopurinol initiation, if relevant.39 Patients who are taking diuretics for hypertension (particularly high-dose thiazide diuretics), for reasons other than heart failure, should be switched to an alternative antihypertensive, if possible.26

Aspirin decreases urate excretion, however, patients who are taking low-dose aspirin for the secondary prevention of CVD should continue doing so.26

Summary

- Losartan is the preferred choice for hypertension

- If possible, avoid diuretics, especially high-dose thiazides

- If indicated, the benefits of low-dose aspirin outweigh the risks

Reducing the risk of kidney stones

Kidney stones composed of uric acid/urate (uric acid stones – uric acid nephrolithiasis) occur in one in seven patients with gout, and those taking uricosuric medicines (e.g. probenecid) are at increased risk.8, 47 Increasing water consumption decreases the risk of uric acid stone formation, e.g. aim for ≥ 2 L fluid daily and avoid any periods of dehydration.8 Treatment with a xanthine oxidase inhibitor (e.g. allopurinol), and reducing purine-rich foods will also decrease the likelihood of uric acid stones forming.26

Sodium bicarbonate (3 – 7.5 g, daily) can be considered for alkalising urine in patients with recurrent uric acid stones (particularly those taking probenecid), available either on prescription or over-the-counter.8, 28 Sodium bicarbonate is available as 840 mg capsules, so multiple capsules will be required to achieve the recommended total daily dose (e.g. four or more); use should continue during urate-lowering treatment until serum urate levels are below the target threshold and tophaceous deposits have resolved (as this indicates reduced urinary uric acid excretion).28

For further information on managing kidney stones and renal colic, see: bpac.org.nz/bpj/2014/april/colic.aspx (published in 2014; some information may no longer be current)

If despite optimising treatment, a patient has persistently high urate levels or continues to experience flares, the next step is to discuss with, or refer to, a rheumatologist. However, first ensure that adherence issues have been discussed and that the patient is effectively implementing lifestyle changes and is avoiding triggering factors such as specific foods in excess or vigorous exercise.

Patients should be discussed with, or referred to, a rheumatologist if they have:8

- A serum urate level consistently ≥ 0.36 mmol/L and the presence of tophi; in patients without tophi, a higher threshold for referral may be considered, e.g. > 0.42 mmol/L

- Persistent flares or progressive joint damage despite a serum urate level that is consistently < 0.36 mmol/L

- Significant renal dysfunction and there are concerns about increasing the dose of urate-lowering treatment