Key practice points:

- Consider the most likely causes of wheeze according to the child’s age, clinical history, risk factors and probability:

- Age <1 year: bronchiolitis is most common

- Age 1 – 4 years: viral upper respiratory tract infection is most common. Consider pre-school asthma if frequent

or severe symptoms, particularly if there is a personal or family history of asthma or atopy.

- Consider bronchiectasis in all children who have chronic wet cough, particularly those in high-risk groups, i.e.

Māori and Pacific children and those from low socioeconomic communities

- Consider an inhaled foreign body if wheeze onset is after a choking episode or wheeze is unilateral

- Two diagnostic classifications of asthma-type wheeze are recommended for pre-school children aged over one year:

infrequent pre-school wheeze and pre-school asthma

- The management of wheeze is determined by the cause, frequency and severity of symptoms, and risk of exacerbations:

- A short-acting beta2 agonist (SABA), used as needed, is recommended for all children aged over one year

with recurrent wheeze, regardless of the diagnostic classification

- An inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) should be added for children with pre-school asthma if they have frequent or severe

symptoms

- Pharmacological treatments, including bronchodilators and ICS, are not indicated for infants with wheeze caused

by bronchiolitis

- Ensure parents and other caregivers receive education about their child’s treatment (including correct inhaler technique

and use of a spacer) and discuss strategies to reduce the risk of exacerbations, e.g. a warm, dry and smoke-free home,

annual influenza vaccination, infection prevention

- Review all children diagnosed with pre-school asthma again at school-age to determine whether an asthma diagnosis

is appropriate, and update their clinical record

Wheeze is defined clinically as a continuous, high-pitched sound due to intrathoracic airway obstruction that is audible

on exhalation.1

While wheeze is often regarded as indicative of asthma, there are other common causes in children aged under five years.

Determining the definitive cause requires a long-term approach, including considering the likelihood of other causes,

ruling out serious congenital or acquired conditions and assessing the child’s response to treatment (see: “Assessing

a child with wheeze”). Regular review of the diagnosis is also important as the pattern of symptoms often changes and

may diminish over time in younger children.2 About half of young children with asthma-type wheeze will not

have asthma at school age or older.3 A personal or family history of atopy is present in the majority of

pre-school children with asthma and makes a future asthma diagnosis more likely.2, 3

Consider other causes of wheeze

Bronchiolitis is the most common cause of wheeze in children aged under one year.3 It is an

acute infection of the lower respiratory tract, most commonly caused by the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).4,

5 Bronchiolitis typically follows an upper respiratory tract infection (RTI) and is characterised by fever, cough,

wheezing and increased respiratory effort.6 Bronchiolitis is usually self-limiting; severity peaks around

day two to three with resolution over seven to ten days.6 A high fever (> 39°C) may indicate another diagnosis,

such as pneumonia, although wheeze is rare in children with bacterial pneumonia. Management of wheeze caused by bronchiolitis

is largely supportive; bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are not indicated.6

For further information on diagnosing and managing bronchiolitis, see: www.bpac.org.nz/2017/bronchiolitis.aspx

Viral RTIs are the most common trigger of recurrent wheeze in pre-school children, who may have six to

eight episodes per year, each lasting one to two weeks.2 Common strains of rhinovirus and coronavirus are

the most frequent causes of viral wheeze.7 Symptoms can include acute wheeze and dyspnoea, usually with cough,

shortly after the onset of an upper RTI.8 Children with acute viral wheeze are unlikely to have chest crackles,

as may be seen in children with bronchiolitis, and will usually not have respiratory symptoms between episodes of viral

infection.6, 8 Management of viral wheeze depends on the frequency and severity of symptoms (see: “Classifications

of pre-school wheeze” and “Managing pre-school wheeze”).

For further information on managing RTIs, see: www.bpac.org.nz/2019/rti.aspx

Bronchiectasis is a lung disease characterised by bronchial dilation, chronic inflammation and infection,

resulting in chronic wet cough. It disproportionately affects Māori and Pacific children and those from low socioeconomic

communities, however, bronchiectasis should be considered in all children presenting with asthma symptoms as these conditions

can co-exist.3

For further information on preventing, diagnosing and managing bronchiectasis in children, see:

www.bpac.org.nz/2020/bronchiectasis.aspx

Consider an inhaled foreign body in children with acute onset wheeze

Foreign body aspiration is common in children aged under three years. Acute symptoms include choking, sudden-onset cough, stridor and respiratory

distress; chronic symptoms include persistent cough, unilateral wheeze or symptoms that mimic asthma, and pneumonia, which is often recurrent.9 The key

finding in a child with an inhaled foreign body is that symptoms began after an episode of choking or severe coughing, however, this may not always be

observed or disclosed, depending on the age of the child.9 Children with a suspected inhaled foreign body require immediate referral to hospital

for investigation and treatment.

The history is the most important aspect of the assessment of wheeze in a young child. People use the word

“wheeze” to describe a wide range of audible breath sounds, including “snuffles” from the upper airway in infants. However,

the clinical definition is specific – a high-pitched whistling sound coming from the chest that is audible on exhalation.1 Ask

the parent/caregiver to describe the child’s symptoms and check that this fits with the definition of wheeze. Ideally,

the child’s wheeze should be assessed during the examination, but this is not always possible. It may be useful to ask

parents to record an episode of suspected wheeze, e.g. on a smartphone.2

Ask parents or other caregivers about:2, 8

- The nature and duration of the wheeze, including whether it is present constantly or intermittently, and previous

episodes; if there is a sudden onset in the absence of symptoms or signs of a viral RTI, consider other causes, e.g.

allergic reaction or inhaled foreign body

- The presence of other respiratory symptoms, e.g. coryzal symptoms

- Exacerbating factors and triggers, e.g. exercise, laughing, crying, cold air, allergies

- The smoking status of the household

- Whether the child has ever had eczema or other symptoms or signs of atopy, or a family history of this

The physical examination is primarily used to help identify potentially serious causes of wheeze. The examination should include:8

- Respiratory rate, heart rate, temperature, oxygen saturation

- Observation of the chest for signs of hyperinflation and respiratory distress, e.g. intercostal in-drawing and accessory

muscle use

- Auscultation to detect wheeze, crackles or focal sounds

- Assessing for concurrent upper RTI, e.g. otitis media or pharyngitis

- Assessing for features of chronic respiratory disease, e.g. growth restriction, digital clubbing, chest wall deformity

Respiratory investigations have a limited role in assessing wheeze in pre-school children. Most children

aged under five years are not able to perform the reproducible expiration needed for lung function testing.2 Chest

X-ray, is generally reserved for cases where the clinical features suggest there may be another cause of wheeze or cough,

e.g. acute pneumonia, structural abnormalities, chronic infection, inhaled foreign body.2

Laboratory investigations are not routinely required for pre-school children with wheeze.

Classifications of pre-school wheeze

In the past, primary care clinicians were encouraged not to make a formal diagnosis of asthma in pre-school children

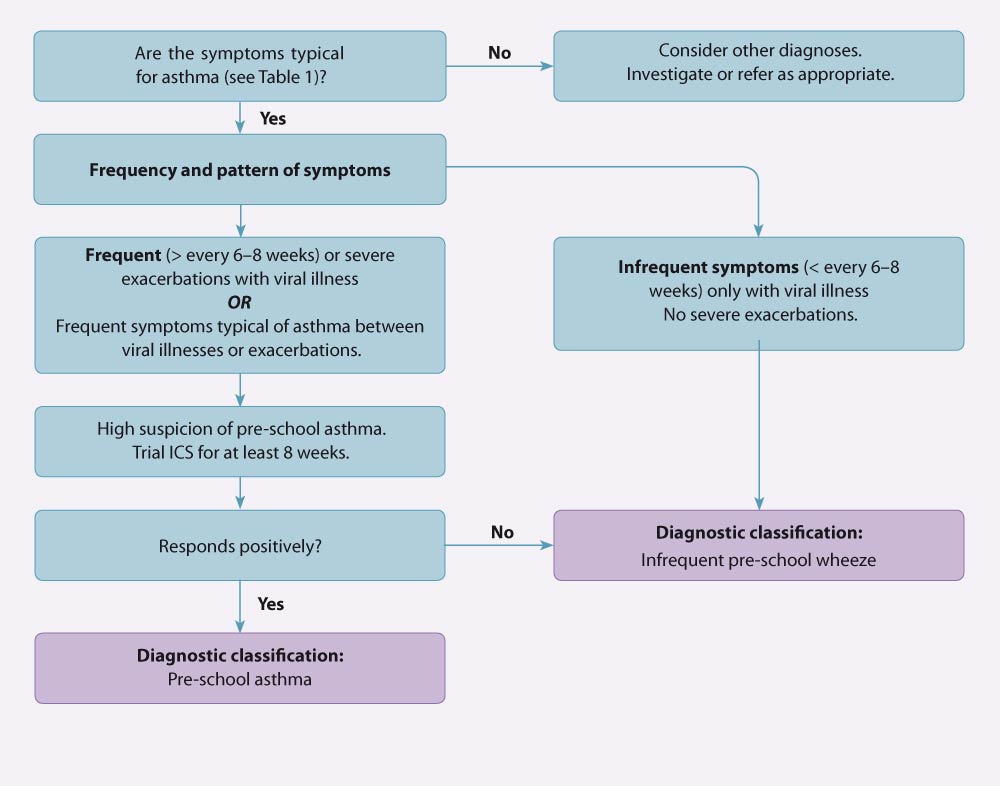

with wheeze.8 In 2017, the Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ guidelines introduced the “pre-school asthma”

diagnosis for children aged 1–4 years. The revised guidelines (2020) recommend the following classifications based on

the frequency, severity and pattern of symptoms, and risk of future exacerbations (see Figure 1 for a diagnostic algorithm):3

Infrequent pre-school wheeze: Mild wheeze that is associated with viral illnesses and is not present at

other times. There is a low risk of severe exacerbations. A trial of ICS is not indicated unless exacerbations are severe.

Pre-school asthma: Frequent (more than every six to eight weeks) or severe exacerbations of wheeze or frequent

symptoms typical of asthma between episodes (see “Making an asthma diagnosis in young children” and Table

1); there may

be regular night waking with cough or wheeze. The child responds positively to a trial of ICS.

N.B. Previous classifications of wheeze (episodic viral or multi-trigger wheeze; transient, persistent or late-onset

wheeze) do not remain constant in many children and their clinical usefulness is now unclear.2, 3, 10

Making an asthma diagnosis in young children

An asthma diagnosis in young children is based on the characteristic pattern of symptoms and signs, risk factors and

response to an ICS, in the absence of an alternative explanation (Table 1).2, 3

Table 1. Features indicative of asthma in children2, 3

| Feature |

Characteristics suggesting asthma |

Wheeze |

Recurrent wheezing, including during sleep or with triggers, e.g. viral infections, activity, laughing, crying

or exposure to allergens or irritants, cold air or stress. May be seasonal. The most sensitive and specific symptom

of pre-school asthma. |

Cough |

Recurrent or persistent non-productive cough that may be worse at night or accompanied by wheezing and breathing

difficulties. Occurs with exercise, laughing, crying or exposure to smoke or e-cigarette vapour, particularly in the

absence of an obvious RTI.

Cough or night cough in the absence of signs of wheeze and breathlessness has a low likelihood of asthma. However,

wheeze may only be detected on auscultation and not by parents. |

Difficult or heavy breathing or breathlessness |

Occurring with exercise, laughing or crying |

Personal or family history |

Personal history of an atopic disorder, e.g. eczema, allergic rhinitis, family history of asthma (first degree

relative), other allergies |

Reduced activity |

Not running, playing or laughing at the same intensity as other children; tires earlier during walks (wants to

be carried) |

Response to treatment trial |

Clinical improvement during at least eight weeks of ICS treatment and worsening symptoms when treatment is stopped |

Figure 1. Diagnostic pathway for wheeze classification in children aged 1–4 years. Adapted from the Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ guidelines (2020).3

Begin with a clear discussion with the parents/caregivers about the likely cause of wheeze, e.g. viral RTI, bronchiolitis

or asthma, the prognosis and expectations of treatment. Explain that the diagnosis may become clearer or change over time

and that pharmacological treatment can be used to relieve symptoms, but does not alter the natural history of the child’s

wheeze, nor prevent the development of asthma.2 Reassure parents that a diagnosis of pre-school asthma does

not mean that the child will have persistent asthma at school age or older.3

Lifestyle interventions for preventing exacerbations of wheeze

Smoke-free environment. A young child presenting with wheeze provides a good opportunity to check the smoking

status of household members and to support them to stop, and in the interim, to at least smoke or vape outside of the

house or car.

For information on smoking cessation, see: www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2015/October/smoking.aspx

Warm, dry homes. If the family is eligible for social support, refer to local housing services, e.g. for

insulation, curtains, housing assistance. Links to local services are available on HealthPathways. Parents or caregivers

of children with asthma that is not fully controlled by medical treatment may be able to access a Child Disability Allowance.

To access HealthPathways, see: www.healthpathwayscommunity.org

For further information on the Child Disability Allowance, see:

www.workandincome.govt.nz

Infection prevention. Discuss hand washing, cough and sneeze hygiene practices to avoid transmission of

infections in the household or early childhood education environments. Children should be up to date with their scheduled

immunisations and be offered influenza vaccination each year. N.B. This is funded for children with asthma who require

regular preventer (maintenance) treatment.

Allergen avoidance. If a specific allergen is identified as a trigger for symptoms it should be avoided

if possible, e.g. long or cut grass, air pollution, pet dander, food item.3 N.B. Dietary modifications, e.g.

dairy avoidance, are not necessary unless there is a confirmed food allergy.3

Ensure healthcare equity for Māori and Pacific children with wheeze or asthma

Asthma is more prevalent in Māori and Pacific children in New Zealand than in those of other ethnicities.3 Māori

and Pacific children with asthma are also more likely to have severe asthma symptoms and be hospitalised, but are less

likely to be prescribed an ICS, have an action plan, or receive adequate asthma education.3, 18

At every review with a Māori or Pacific child with wheeze or asthma, ensure they have:3

Consider referring to a local Māori or Pacific health provider for additional support, if available.

* Samoan term for extended family

Resources for Māori and Pacific children with asthma are available from:

www.asthmafoundation.org.nz/resources/page/2

Pharmacological treatment is guided by wheeze classification

Children with infrequent pre-school wheeze should be managed with an as needed short-acting beta agonist

(SABA) reliever.3 ICS are not indicated unless symptoms are frequent or severe, in which case an ICS trial

may be considered, and the classification of wheeze revised accordingly.3

Children with pre-school asthma should be managed with an as needed SABA reliever with twice daily ICS

added if symptoms are frequent, severe or there is a high risk of exacerbations (see: “Initiating maintenance

ICS treatment).3 Long-acting

beta agonists (LABAs) should not be used in children aged under four years and never prescribed without an ICS.3 Instead,

use an oral leukotriene receptor antagonist (e.g. montelukast) if add-on treatment is required (see: “Consider

adding montelukast if symptom control is poor on ICS”).3

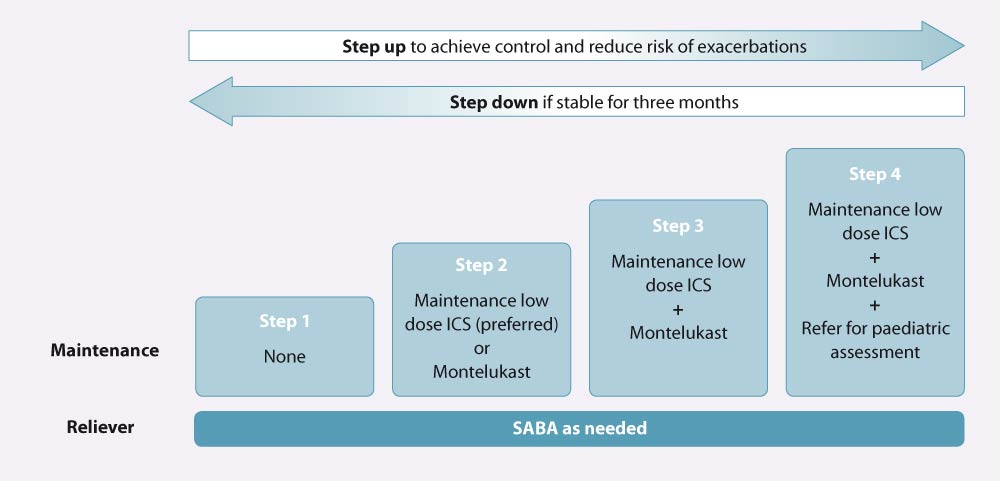

A stepwise treatment algorithm is presented in Figure 2. Stepping up or stepping down treatment is guided by symptom

control and risk of exacerbations.3 Before stepping up, check inhaler technique (including use of a spacer),

adherence, understanding of the management plan and any barriers to its implementation.3 Once symptoms have

been well-controlled for at least eight weeks, consider stepping down and reassess control after a further four weeks.3

Best practice tip: Correct inhaler technique is essential to achieving and maintaining good asthma control.

All health care professionals involved in caring for patients with asthma should regularly review inhaler technique, including

use of a spacer. When teaching inhaler technique, get the parent/caregiver to demonstrate how they would help their child

to use the device. Patient information is available from: www.asthma.org.nz/pages/all-about-spacers

Figure 2. Stepwise treatment of pre-school asthma. Adapted from the Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ guidelines (2020).3

Initiating maintenance ICS treatment

ICS, delivered via metered dose inhaler (MDI), spacer and mask,* are recommended for children with any of the following:3

- Asthma symptoms >2 times/week

- Use of a reliever >2 times/week

- Regular night waking with symptoms in the past month

- An exacerbation requiring oral corticosteroids in the past year

Twice daily, low dose ICS treatment (Table 2) is the most effective treatment of recurrent wheeze and is recommended

for children with frequent symptoms.3, 11

Intermittent standard dose ICS treatment (Table 2), initiated at the first sign of an upper RTI, may be

considered for those with less frequent symptoms who are not on maintenance ICS treatment. This approach has been shown

to reduce oral corticosteroid use in children with moderate to severe symptoms associated with viral illnesses (also see:

“Reviewing the safety of corticosteroids in young children”).3, 11

* Masks are recommended for children aged under two years; children aged two to four years may be able to transition

to no mask.3

Table 2. Low and standard ICS doses for pre-school children, adapted from the Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ guidelines.3

| ICS (funded brand name)* |

Low dose |

Standard dose

N.B. Generally only used in children aged under 5 years for intermittent treatment |

Beclomethasone dipropionate

(Beclazone) |

200 micrograms/day

Prescribe:

- Beclazone 100, one actuation, twice daily

OR

- Beclazone 50, two actuations, twice daily

|

400–500 micrograms/day

Prescribe:

- Beclazone 100, two actuations, twice daily

OR

- Beclazone 250, one actuation, twice daily

|

Beclomethasone dipropionate ultrafine

(Qvar) |

100 micrograms/day

Prescribe:

- Qvar 50, one actuation, twice daily

|

200 micrograms/day

Prescribe:

- Qvar 100, one actuation, twice daily

|

Fluticasone propionate

(Flixotide MDI, Floair†) |

100 micrograms/day

Prescribe:

- Flixotide (MDI) 50, one actuation, twice daily

OR

- Floair 50†, one actuation, twice daily

|

200 micrograms/day

Prescribe:

- Flixotide (MDI) 50, two actuations, twice daily

OR

- Floair 50†, two actuations, twice daily

|

* Budesonide (Pulmicort) has been excluded as this is delivered via turbuhaler, which pre-school children are unlikely to be able to use

† From 1 September, 2020, the Floair brand of fluticasone metered dose inhaler (MDI) will no longer be funded. For further

information, see: https://pharmac.govt.nz/news-and-resources/consultations-and-decisions/decision-to-award-sole-supply-for-fluticasone-and-fluticasone-with-salmeterol-metered-dose-inhalers/

Consider adding montelukast if symptom control is poor on ICS

A trial of montelukast (fully funded, available as a chewable tablet), a leukotriene receptor antagonist, is recommended

as an add-on treatment for children with pre-school asthma with poor symptom control on ICS, once adherence and correct

inhaler technique have been confirmed.3 Montelukast may also be considered as an alternative to ICS at Step

2 of the treatment algorithm (Figure 2), if ICS are not able to be used.3

The evidence supporting the effectiveness of montelukast for treating wheeze is conflicting. Some individual RCTs have

shown benefit, however, pooled analyses have been limited by the different end points of individual trials.12–14

Refer to the NZFC for information on dosing and adverse effects: www.nzfchildren.org.nz/nzf_1673

Oral corticosteroids are not routinely recommended for pre-school children

Oral corticosteroids may be beneficial for some pre-school children with severe acute wheeze, but current evidence does

not strongly support use in this age group.15 The Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ guidelines, and a

Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand position statement, recommend reserving the use of oral corticosteroids

in children aged under five years for those with an exacerbation severe enough to require hospitalisation.3, 16 If

needed, oral prednisolone (liquid) can be given at 1–2 mg/kg per day, up to maximum of 40 mg daily, for 3–5 days.17 Treatment

can be stopped following a short course without tapering the dose.

A diagnosis of asthma in early life can have unintended consequences in later life even if symptoms do not persist,

including limiting or complicating certain employment opportunities (e.g. police) and recreational activities (e.g. diving),

and having implications for travel and life insurance. If a child is diagnosed with pre-school asthma, review them again

at school-age to determine whether an asthma diagnosis is still appropriate, and ensure the clinical notes are updated.

Investigations of lung function testing (spirometry or peak expiratory flow) may assist an asthma diagnosis in school-age

children.3 If asthma is diagnosed, a review of the child’s response to treatment (see: “Pharmacological

management of asthma in children aged 5–11 years”) and reconsideration of the diagnosis after three months is recommended.3

For further information on diagnosing asthma in school-age children, see: www.nzrespiratoryguidelines.co.nz/uploads/8/3/0/1/83014052/arf_nz_child_asthma_guidelines_update_30.6.20.pdf

A Goodfellow Unit podcast with Dr David McNamara on diagnosing and managing asthma in children aged under

five years is available from: www.goodfellowunit.org/podcast/asthma-under-five-year-olds

Reviewing the safety of corticosteroids in young children

Inhaled corticosteroids

ICS are generally considered to be safe and the benefits of treatment far outweigh the risks, particularly when used

at a low dose,2 however, there are few studies investigating the systemic effects of ICS in children aged

under five years. At higher doses (i.e. standard dose or higher – see Table 2), ICS have adverse effects on height growth

in the first one to two years of treatment and on the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis.2, 19 Ongoing treatment

does not appear to result in further reductions in height.2 It is not known whether the initial reduction

in height in children who started ICS before age five years persists into adulthood. However, data from a randomised controlled

trial found that adult height was reduced by 1.2 cm in people with mild to moderate asthma who were treated with budesonide

for four years (400 micrograms, daily) when aged 5–13 years, compared to placebo.20 Monitor the child’s height

at least yearly. If height growth velocity is reduced, also consider other reasons for this, e.g. poor asthma control,

frequent use of oral corticosteroids or poor nutrition.2

Local adverse effects of ICS such as hoarseness and candidiasis are rare in children aged under five years.6 The

risk of candidiasis can be reduced by rinsing the mouth with water following dose inhalation.17

Oral corticosteroids

The risks of corticosteroid treatment are greater with oral than inhaled formulations. Adverse effects associated with

short-term oral corticosteroid use may include changes in appetite, behaviour and mood.21 While there is

little risk of long-term suppression of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis with short-term treatment, risk can accumulate

if treatment is frequent (four or more courses per year).21 Recurrent oral corticosteroid use may reduce

bone mineral density, particularly in boys.21