Watch this space. Long COVID is an evolving area of clinical research, and guidance is likely to change frequently. Given the diverse clinical picture associated with this condition, it is not a “natural fit” for any one medical specialty, therefore primary care clinicians will often be responsible for leading the management and support of affected patients. The perspectives and recommendations presented here are intended as a general guide and are current as of the publication date; they are largely based on content from the 2022 Ministry of Health "Clinical rehabilitation guideline for people with long COVID (coronavirus disease) in Aotearoa New Zealand". We will aim to provide updates as further evidence emerges.

Update (Jan, 2025): The Ministry of Health has published an updated evidence review on long COVID. This acknowledges ongoing challenges in understanding symptom prevalence but highlights a narrower subset of prolonged symptoms more confidently attributed to infection with SARS-CoV-2. The most prevalent symptoms among adults include:

- Fatigue

- Poor concentration/memory

- Shortness of breath

- Loss of taste or smell

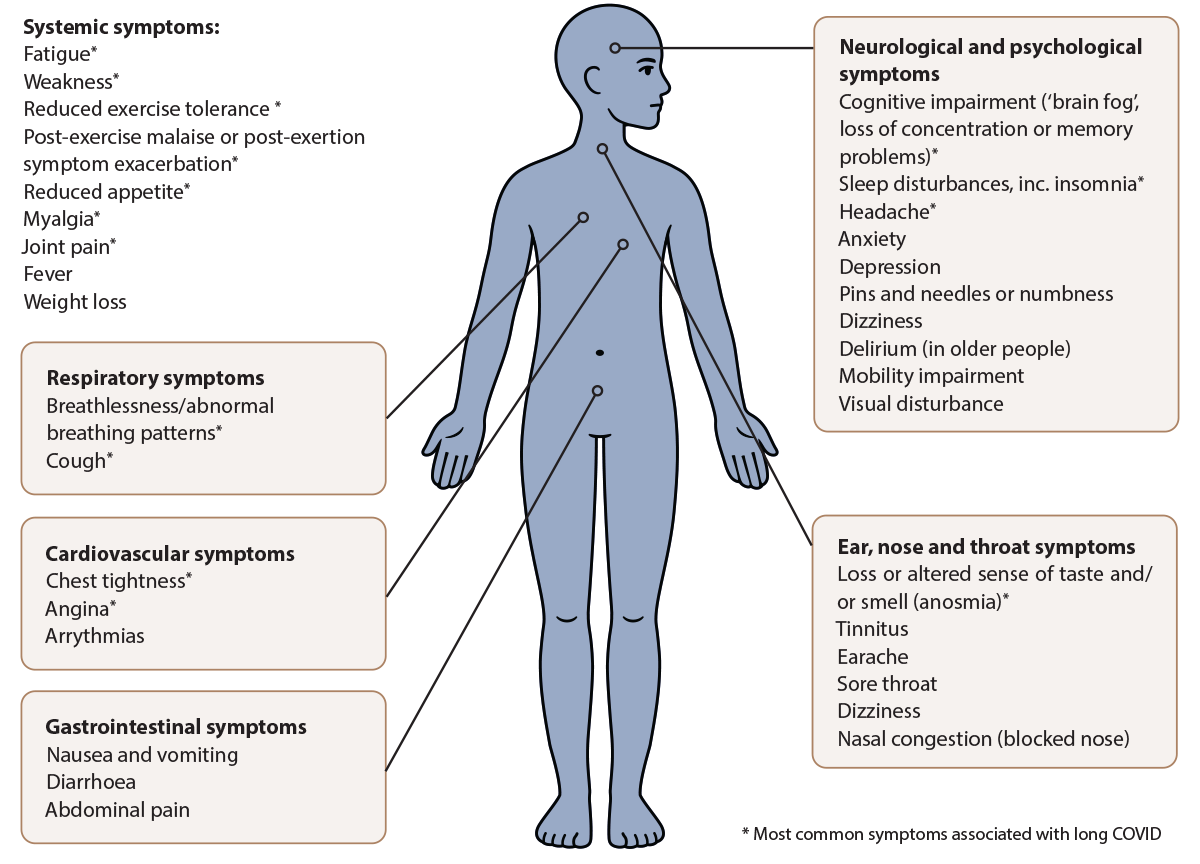

Common symptoms in children and adolescents are similar, but also include cough and headache. This work concludes that “in the absence of definitive diagnostic criteria, this subset can inform a refined, iterative definition of long COVID-19, both internationally and in New Zealand” and in turn “facilitate accurate surveillance and targeted resourcing for clinical and wellbeing support”. However, it highlights that heterogeneity between study designs and population groups investigated limits the interpretation of evidence, and that other less common symptoms can still also be associated with long COVID (as detailed in Figure 2 of this article).

For further information, see “Prolonged Symptoms Attributable to Infection with COVID-19” available at: www.health.govt.nz/publications/prolonged-symptoms-attributable-to-infection-with-covid-19

Key practice points:

- Long COVID can be diagnosed in patients with symptoms and signs of COVID-19 that continue for more than 12 weeks and are not explained by another diagnosis

- While long COVID is more common in those who experienced severe acute COVID-19, it can occur in any patient including those with a mild initial presentation, regardless of age

- The pathophysiology of long COVID is unclear and likely heterogeneous. It can be associated with a wide range of general and organ-specific symptoms and signs, which may occur in overlapping clusters, relapse and change over time. Common features include fatigue, difficulty concentrating (brain fog), chest pain or tightness, cough, breathlessness and other abnormal breathing patterns.

- There are currently no specific laboratory parameters diagnostic of long COVID. The diagnostic work-up will vary between patients but should broadly include:

- A clinical history of their COVID-related illness, symptoms and how they were managed. Considering any pre-existing conditions and how they may be associated with or complicate presenting features.

- Physical examination and further investigations tailored to the patient’s history and presenting features. Laboratory tests may help to provide further information and exclude other causes based on predominant symptoms; avoid requesting an excessive number of tests without indication.

- Ruling out serious underlying organ damage

- Specific codes are available to record a diagnosis of long COVID in the patient record once alternative diagnoses have been excluded

- Most patients can be managed within primary care. The initial focus is achieving symptom control and identifying complications early. However, the care plan should also consider and address the wider consequences of ongoing symptoms, including effect(s) on quality of life, emotional distress and psychological implications for the patient and their family/whānau. Not adequately managing these factors can impede and prolong recovery.

- All plans should include tailored education, self-care advice and realistic goals – all of which should be culturally appropriate

- There are currently no medicines indicated specifically for the treatment of long COVID (but numerous clinical trials are ongoing)

- Patients with complex presentations or persisting features are likely to benefit from multidisciplinary care involving allied health professionals, e.g. occupational therapists, physiotherapists, psychologists. There is currently no specific national funding for accessing these additional services, but work is ongoing to test the viability of regional care pathways (as of June, 2023).

- It is not possible to predict the time-course for recovery from long COVID; this depends on individual risk factors, as well as the severity and spectrum of symptoms. However, patients should be reassured that by adhering to management advice they will usually improve progressively over time.

Long COVID (also referred to as long COVID-19, post-acute COVID-19 syndrome and post-acute sequelae SARS-CoV-2 infection [PASC]), is characterised by:1–3

- Symptoms and signs consistent with COVID-19 that develop during or after an infection; and

- Continue for more than 12 weeks; and

- Are not explained by an alternative diagnosis

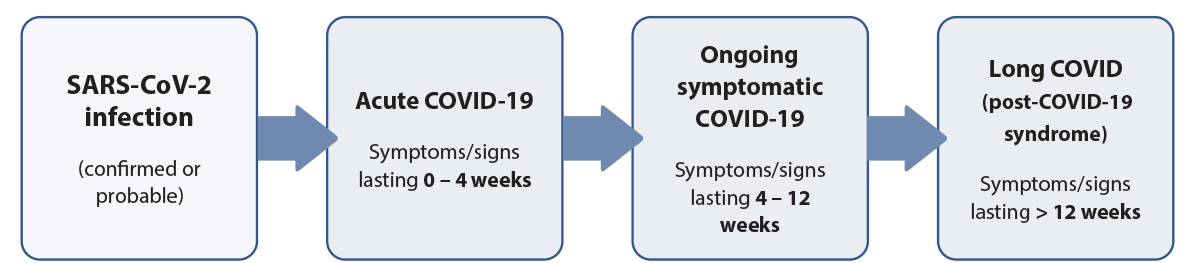

Long COVID is distinguished from “acute COVID-19” and “ongoing symptomatic COVID-19” according to the duration of symptoms and signs (Figure 1).1, 4 A positive SARS-CoV-2 test (i.e. RAT or PCR) at the time of assessment is not required for diagnosing long COVID,1, 4 assuming the patient has either: 1) a historical positive test result during the preceding COVID-19 phases (Figure 1); or 2) they meet the case definition and have a history indicative of probable infection, e.g. patient is a household or workplace close contact of someone with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The pathophysiology of long COVID is currently unclear. In addition to possible organ damage caused during acute infection, other proposed mechanisms include ongoing chronic inflammatory processes, immune system dysfunction, viral persistence, endothelial dysfunction and microvascular blood clotting.5, 6 Psychological mechanisms have also been implicated as contributing and exacerbating factors.7 For example, psychological distress can be both a symptom and a risk factor for long COVID, and other presenting features can overlap with those caused by anxiety, e.g. fatigue, chest pain, difficulty concentrating.7

Even mild symptoms, if persistent, can have a substantial effect on a person’s quality of life, limiting their ability to engage in work, education and recreation.1 More severe symptoms can cause significant functional impairment and, in some cases, may be a sign of serious underlying damage.5, 6

For a comprehensive review on the pathophysiology and mechanisms of long COVID, see: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41579-022-00846-2

Figure 1. Time-based distinction between different COVID-19 classifications.1

A closer look at prevalence and risk

It is estimated that 6 – 20% of people infected with SARS-CoV-2 worldwide experience features consistent with long COVID.8, 9 However, reported figures vary significantly between studies depending on the case definition and methodology used.

There is insufficient evidence to predict who will experience long COVID. It is more common among people with severe acute COVID-19, but can also occur in those who experienced mild-to-moderate symptoms.1 Emerging evidence has highlighted other potential risk factors for long COVID, including female sex, high BMI, pre-existing co-morbidities (particularly asthma, hypertension or a psychiatric condition) and hospitalisation during acute COVID-19.6, 10, 11 However, given the evolving nature of this research, it is possible that proposed risk factors may be revised over time as further evidence emerges. For example, older age was initially suggested as a risk factor for long COVID based on evidence from individual studies;12 a subsequent meta-analysis, however, did not confirm this association.11

Research on long COVID in New Zealand is emerging

The prevalence of long COVID in New Zealand is not yet known as it is an evolving clinical diagnosis. There has been some preliminary study gathering data on people who self-identified as having long COVID. In the 2023 Ngā Kawekawe o Mate Korona study, approximately one in five people reported having symptoms that persisted more than three months after their acute infection,13 which is broadly consistent with international prevalence figures for long COVID.8, 9 Further robust investigation is required to derive quantitative prevalence data in New Zealand based on clinically confirmed diagnosis.

Qualitative findings of the Ngā Kawekawe o Mate Korona study give some insight into the experience of long COVID in New Zealand, demonstrating the wide-reaching impacts across all aspects of Hauora wellbeing, as well as people’s ability to engage in daily tasks and employment.13 Some survey participants described “how the illness had challenged their sense of identity”, forcing them to “make major changes in their lives and losing their sense of purpose”.13 Others emphasised the cultural impact that ongoing symptoms can have, such as “no longer being able to smell and taste food, so important to many aspects of tikanga Māori”.13

The most commonly reported persisting symptoms in people with long COVID include fatigue, difficulty concentrating (brain fog), chest pain or tightness, cough, breathlessness and other abnormal breathing patterns (Figure 2).1, 6, 14 However, more than 200 different symptoms and signs have been reported in the wider literature.6, 8 Features usually occur in overlapping clusters, that can fluctuate, change and relapse over time; they can affect any body system.1, 4 In some cases, symptom clusters are used to further define sub-classifications of long COVID, e.g. PASC-cardiovascular syndrome (PASC-CVS) which is a “heterogeneous disorder that includes widely ranging cardiovascular symptoms, without objective evidence of cardiovascular disease using standard diagnostic tests”.15 There can also be considerable overlap between the symptoms seen in long COVID presentations and those associated with other post-viral illnesses such as myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).1,6

Figure 2. Symptoms and signs associated with long COVID.1, 6, 14

There is no single diagnostic test for long COVID

N.B. The diagnostic work-up of patients with suspected long COVID depends on the individual patient and their characteristics. Guidance regarding specific investigations varies across the literature as it is a developing area of research. The following section details recommendations from current guidelines, however, this advice should not override clinical judgement. Check regional HealthPathways for further advice about establishing a diagnosis of long COVID.

For patients presenting in primary care with features suggestive of long COVID, a clinical history should be taken which includes identifying:3, 4

- A history of acute COVID-19. There does not need to be a previous record of COVID-19 in the patient’s notes; it is sufficient to ask whether they have had COVID-19, either confirmed (e.g. with at-home RAT) or probable (e.g. having respiratory symptoms after being a close contact of a confirmed case). A negative RAT at the time of assessment does not exclude long COVID if the patient otherwise fits with the case definition.

- The type and severity of previous and current symptoms, including any factors that may trigger or exacerbate symptoms

- The timing and duration of symptoms since the patient’s acute COVID-19 phase

- Other pre-existing conditions which may explain or complicate the current presentation, and whether the symptoms and signs of these co-morbidities were exacerbated during the acute COVID-19 phase

- Any medicines used for the treatment of long COVID symptoms (including over-the-counter products) and whether hospitalisation was required during the acute COVID-19 phase (including details regarding management, complications, follow-up planned). N.B. there is not enough evidence to determine whether the use of antivirals during the acute COVID-19 phase reduces the risk of long COVID.

- Any mental health sequelae resulting from COVID-19 or its treatment; ask the patient how their symptoms have impacted on daily life, work, education and financial situation

Perform a general physical examination including pulse, blood pressure and oxygen saturation.3, 4 The need for other examinations is guided by specific symptoms and findings. For example:

- If cough and dyspnoea is present, perform chest auscultation

- If autonomic dysfunction is suspected, assess for postural hypotension/tachycardia

- If altered sense of taste or smell is present, examine the nasopharynx for other potential causes, e.g. nasal polyps, chronic rhinosinusitis

- If musculoskeletal issues are reported, assess the affected areas for tenderness and range of motion

Be selective when considering further investigations

If a more likely diagnosis is not revealed, the need for further investigations depends on the patient’s presenting features, history and examination findings.4 As a general rule, excessive testing should be avoided in the absence of red flags (see: “Situations requiring more urgent action”) as non-specific abnormalities are common following acute COVID-19 illness.

-

If needed, baseline laboratory testing can be requested to expand on the clinical picture (e.g. FBC, creatinine/electrolytes, LFTs, CRP), with additional tests added based on reported symptoms to exclude other potential diagnoses (e.g. TSH and ferritin if fatigue is a concern).3, 17 Some studies indicate an increased risk of diabetes following COVID-19;18 while further information is required to support this relationship, HbA1C testing can be included for select patients, e.g. those with other associated risk factors.

- Consider additional investigations in patients with predominant body system-specific symptoms, for example:3, 4, 16, 17

- Cardiovascular features – an ECG should be performed and further laboratory testing considered, e.g. brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and troponin testing

- Respiratory features – consider lung function/exercise tolerance testing, as appropriate. Spirometry and diffusion capacity testing are commonly suggested in the literature, however, access is variable across New Zealand. Chest X-ray may be useful in patients with significant breathing problems, particularly smokers or those with other respiratory co-morbidities (e.g. COPD, asthma).

Practice point: SNOMED CT, ICD-10 and other PMS codes for recording a diagnosis of long COVID can be found at: https://www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/for-the-health-sector/covid-19-information-for-health-professionals/recording-covid-19.

Situations requiring more urgent action

In most cases, patients with long COVID can be managed in primary care (see: “Management principles for patients with long COVID”).3 However, clinicians should remain alert for patients with features that may require more urgent action (Table 1).1, 3 If symptoms are severe or concerning for any reason, or are not improving in immunocompromised patients, secondary care or emergency department referral is recommended.1, 20

Table 1. Red flags in patients with long COVID.1, 3

| Red flags – may require urgent action or referral |

| Heart failure |

| Acute coronary syndrome |

| Myocarditis |

| Cardiomyopathy |

| Venous thromboembolism |

| Chest pain |

| Chest tightness, worsening or increasing palpitations, dyspnoea, desaturation on exertion |

| Pulmonary embolism |

| Post-exertion symptom exacerbation |

| Coagulation dysfunction |

| Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (PoTS) |

| Functional neurological disorder |

| Renal failure |

| Type 1 diabetes |

| Suicidal ideation |

| Paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-Ts) or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)* |

| Paediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome |

*These are different terms describing a rare systemic illness that occurs in some children after COVID-19 infection.21 PIMS/MIS-C involves persistent fever and extreme inflammation following SARS-CoV-2 exposure and can result in medical emergencies such as shock and organ failure. Prompt paediatric or emergency referral should be considered in any child presenting with:

- Fever and who is critically unwell

- Persistent fever for three or more days, and looks unwell

- Persistent unexplained fever for five or more days

For further information, see: https://starship.org.nz/guidelines/covid-19-associated-multi-system-inflammatory-conditions-pims-ts-mis-c/

A management plan for a patient with long COVID should aim to:1, 3

- Achieve symptom control (once more serious pathology has been excluded)

- Identify any potential complications early

- Optimise the management of any pre-existing long-term conditions

Given the diverse spectrum of possible presentations, care pathways will differ considerably between patients. Table 2 provides a brief summary of primary care management recommendations for a patient with common long COVID features.

In addition to considering the physical aspects of rehabilitation, guidelines also emphasise that management should identify and address the wider consequences ongoing symptoms may have, including effect(s) on quality of life, emotional distress and psychological implications for the patient and their family/whānau (a “holistic” approach to care).1, 3, 4, 22 Evidence suggests that psychological and psychosocial factors can impede the rehabilitation process if they remain unaddressed or inadequately managed. For many patients, uncertainty associated with the underlying cause of long COVID and its recovery timeline (see: “Expected time to symptom resolution”) will be a major source of concern. Particular consideration also needs to be given to tailoring support for Māori and Pacific peoples (e.g. inclusion of family/whānau in the care plan), people with a disability, children and frail elderly people.1

- Patient education and reassurance should be the foundation of any management plan. This information should be easily accessible, tailored to their level of health literacy and culturally appropriate.1

- Encourage self-management. Once equipped with information and symptom recovery advice, patients should be encouraged to take an active role in their rehabilitation and apply self-management strategies where possible.3 Some patients may find it useful to track their symptoms using a diary to help identify patterns and changes over time.

- Returning to work. Symptoms associated with long COVID can have a significant impact on a person’s capacity to engage in work;1 patients should be advised to initiate discussions early with their employer to establish specific needs, and to plan for a gradual or phased return to work.23, 24 This may involve changes to the work environment and flexibility around working arrangements, e.g. reduced workload or hours, more frequent break times, remote working.23, 24 However, the capacity for such accommodations will depend on the specific employer and the type of work being undertaken. Clinicians can support patients by providing a medical certificate (if appropriate) and a letter outlining recommendations about return to work plans. If employees deplete all of their sick leave and annual leave, they may qualify for financial assistance from Work and Income (e.g. disability allowance) if they meet certain criteria.24

- Support for returning to school. For children and young people, consider the impact the ongoing symptoms may be having on their engagement in school/education; for those with a high absence rate, a progressive symptom-led return to classroom attendance should be encouraged, facilitated by options such as home-based, online or hybrid learning (if possible).1

- If required, support from a special education needs coordinator (SENCO) or Northern/Central/Southern Health School teacher may help to establish a tailored plan with the patient and their family/whānau.

Table 2. General management recommendations for patients with long COVID in primary care. Adapted from Ministry of Health, 2022.1, 3, 25

N.B. Links to selected external resources have been included. For a comprehensive list of resources to inform and support clinicians in applying these recommendations, see: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/summary_of_symptoms_and_management_resources_for_clinicians.v3.pdf

Outcome measures and care action plans |

|

Fatigue |

- Emphasise the importance of taking time to recover within energy limits and provide information about fatigue management and “pacing” activities. For additional information on pacing, see:

- Tailor advice to the patient’s lifestyle, physical capabilities, culture, environment and social demands. Be aware that fatigue (and ‘brain fog’) can make it more difficult for patients to understand and process information.

- Referral to an occupational therapist may be beneficial for patients requiring additional support, particularly those struggling to return to work, education or other daily routines

|

Post-exertional malaise and post-exertional symptom exacerbation |

- Can be triggered by physical, cognitive, mental or emotional reasons, with onset immediately or up to 24 – 72 hours post-exertion. For further information, see: https://www.jospt.org/do/10.2519/jospt.blog.20220202

- Advise patients with persisting symptoms to be cautious with returning to exercise or strenuous activities. Activity engagement should ideally be conservative, e.g. limited to 55 – 60% of maximum heart rate (220 minus age) until two to three weeks after symptoms resolve. While gradual exercise re-engagement should be encouraged, this should be based on symptom-led pacing, rather than planning regular incremental increases in frequency/intensity/duration (i.e. “graded exercise therapy”).

- Management may also include breathing retraining and establishing a symptom-free baseline. Referral to an occupational therapist or physiotherapist may be beneficial for patients requiring additional support.

|

Breathing pattern disorder |

- In general, patients should be advised to continue doing daily activities even if they experience some breathlessness. Positional changes can sometimes ease symptoms. Breathing control exercises may be useful to improve respiratory muscle conditioning. Examples are available at: https://longcovid.physio/breathing-pattern-disorders

- Referral to a physiotherapist may be beneficial for patients requiring additional support

|

Chest pain |

- If serious cardiac/respiratory sequalae have been excluded, provide reassurance and advise patients seek urgent medical attention for any worsening symptoms

|

Cough |

- Advise patients to keep well hydrated and to trial other supportive practices such as drinking hot beverages with honey/lemon, lozenges, breathing through the nose, changing position to help drain phlegm and other sputum clearing techniques (for productive cough)

- The Leicester cough questionnaire may be useful to assess the impact of cough on quality of life and to track changes over time: http://centerforcough.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/leicester-cough-quest.pdf

|

Thought processing, memory and “brain fog” |

- Reassure patients that these features should improve over time and provide supportive care which focuses on addressing fatigue and managing any stress/mood changes

- Pacing strategies can help conserve mental energy, as well as frequent breaks and relaxation exercises, e.g. breathing exercises or meditation. Encourage use of a white board, notepad or electronic alerts to keep track of tasks in the short-term.

- Specific management advice for patients is available at: https://www.yourcovidrecovery.nhs.uk/i-think-i-have-long-covid/effects-on-your-mind/memory-and-focus/

|

Sleep issues |

|

Dysautonomia, orthostatic intolerance and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (PoTS) |

- Involves symptoms which occur when sitting or standing, e.g. dizziness, fainting, light-headedness or nausea. Screening information is available at: https://www.potsuk.org/about-pots/diagnosis/ (e.g. the NASA lean or active stand test).

- Advise patients to avoid any identified triggers, increase fluid intake (to at least 2 – 3 L/day) and salt intake (to at least 6 g/day unless contraindicated, e.g. due to hypertension, chronic kidney disease or heart failure), as well as trialling muscle contraction/relaxation exercises. Some patients may find medical grade compression garments useful.

- Further information for clinicians is available at: https://www.potsuk.org/potsfor-medics/gp-guide/

|

Communication or swallowing issues |

- If a patient is taking long-term medicines and swallowing affects their ability to safely ingest them, review whether changes to the medicine form can be made

- Patients with increasing communication or swallowing difficulties should be immediately referred to a speech-language therapist for urgent assessment (particularly if they are already prone to chest infections or have pre-existing breathing difficulties)

- Resources from the New Zealand Speech-language Therapists’ Association can be found here: https://speechtherapy.org.nz/for-whanau/resources-for-whanau-and-carers/

|

Changes in taste and smell |

- Provide reassurance that changes in taste/smell are common and usually resolve with time

- Patients should be encouraged to eat foods that are most appealing, while maintaining a balanced and nutritious diet

|

Joint and muscle pain or stiffness |

- Encourage gentle, full range of motion exercise routines; progressively increase intensity/duration over time according to tolerance

- Consider as-needed use of simple analgesics, non-pharmacological strategies (e.g. heat/cold treatments) or physiotherapist referral, if required

|

Mental health challenges |

- Assess for anxiety and depression and manage accordingly if present

- Successful symptom management can contribute to improvements in mental health (including anxiety, depression and low mood) but setting realistic expectations is important. Psychological mechanisms should also be considered as a possible contributing factor or cause of ongoing symptoms.

- Advise patients to keep a routine, stay connected with friends and family/whānau, and apply other general healthy living advice, e.g. healthy eating, limiting alcohol intake. Peer-support groups can also be beneficial, if available locally.

- Some patients with long COVID may experience symptoms of trauma/post-traumatic stress disorder and suicidal ideation, therefore the threshold for initiating more intensive mental health intervention(s) should be lower

|

Vaccination |

- If not up to date with recommended COVID-19 vaccinations, discuss their importance. Adults can receive a booster if they have completed their primary course. An additional bivalent booster is available for selected groups if it has been at least six months since their previous vaccine dose or positive COVID-19 test (or earlier at the discretion of the clinician, following informed consent).

- For further information on vaccine eligibility and timing, see: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/immunisation-handbook-2020/5-coronavirus-disease-covid-19#23-5

|

There are no medicines specifically indicated for long COVID

There are several antiviral medicines approved for the treatment of patients with acute COVID-19 at risk of severe disease (e.g. nirmatrelvir with ritonavir), but there are no medicines validated for directly treating long COVID.1, 26 There is also insufficient evidence to determine whether antiviral use at the time of acute COVID-19 infection reduces the risk of long COVID. As of June, 2023, there are numerous ongoing trials investigating the efficacy of different treatments to target the suspected causes of long COVID; these involve both repurposed and novel medicines.6

Pharmacological treatment in patients with long COVID primarily involves optimising the management of pre-existing long-term health conditions, and prescribing medicines for specific symptoms as appropriate, e.g. simple analgesia for patients with musculoskeletal pain.1

Clinicians often experience pressure to prescribe some form of treatment when managing patients with long COVID. Navigating these discussions and balancing patient expectations against evidence-based practice can be a significant challenge. If considering prescribing a medicine, assess whether there is any published or anecdotal evidence of effectiveness, and by what mechanism the treatment could provide benefit. Lastly, consider whether any adverse effects of the medicine, or interactions with other medicines, would outweigh any potential benefits.

Some research suggests antiplatelet use (e.g. aspirin) may improve clinical outcomes in patients hospitalised with acute COVID-19;27 considering the possible role of thrombosis and inflammation in long COVID pathophysiology, there has been speculation that low-dose antiplatelet treatment may also benefit patients with long COVID.28 However, randomised controlled trial evidence for this approach is lacking and any decision to prescribe aspirin should be made in accordance with the patient’s cardiovascular disease risk.29

If a specific nutritional deficiency is suspected or identified during the diagnostic work-up, supplementation may be appropriate (e.g. vitamin B12, vitamin D, iron), however, there is currently no convincing evidence for routine treatment in patients with long COVID.

The importance of multidisciplinary care

Integrated multidisciplinary care is consistently highlighted in guidelines as being important for successful long COVID management.1, 4, 22 This approach can help to more effectively address the often wide array of long COVID symptoms that patients can experience, and may include a combination of in-person and telehealth services.4

Allied health professionals who can support the recovery of patients with long COVID in the community include:1

- Occupational therapists – develop plans to achieve personal self-care, work and leisure objectives, including providing advice on pacing strategies and recommending adaptations to a patient’s equipment or environment

- Physiotherapists – focus on alleviating the physiological consequences of COVID-19. Physiotherapists interpret the findings of individualised assessments and help guide tailored rehabilitation programmes with specific physical interventions and exercise(s); they may be particularly useful when respiratory or musculoskeletal symptoms are a key ongoing issue.

- Clinical exercise physiologist – assess the causes of exercise intolerance or reduced functional capacity, and create individualised exercise-focused interventions to restore or alleviate loss of function

- Dietitians – assess the nutritional needs of a patient and create individual plans, taking into account other underlying conditions, swallowing difficulties, lifestyle, social or cultural factors. Particularly relevant in patients with ongoing poor appetite, unintentional weight loss or gastrointestinal symptoms.

- Speech language therapists – provide specialist assessment and rehabilitation for patients with communication or swallowing difficulties

- Psychologists – can help manage anxiety or distress, sleep disturbances, and provide coping strategies for processing the effects of ongoing symptoms

- Social workers – evaluate patient and family/whānau situations and needs according to their unique structural, economic, social and cultural challenges. This information can then be used to determine and prioritise goals that will promote wellbeing, resilience and ability to cope with stress.

Co-ordinating the transition between different care providers and settings is an evolving challenge in New Zealand. The Ministry of Health is continuing to develop long COVID rehabilitation guidance and its approach to service delivery; it is possible that more formal care pathways will be established once further evidence is available.

There is currently no national funding scheme for patients with long COVID requiring general practice consultations or allied health professional support, i.e. patients access services and are charged co-payments (as applicable) as for any other health condition.30, 31 Patients wanting timely access to allied health professional services will most likely have to self-fund appointments; this presents a significant barrier in achieving equitable health outcomes across patient groups.30

There is no specific time course for recovery from long COVID; it appears to depend on individual risk factors (including psychological factors) and the severity and spectrum of symptoms experienced. In general, expected timeframes for recovery from COVID-19 specific symptoms are:1

- Four weeks for myalgia, chest pain and sputum production

- Six weeks for cough and breathlessness to be significantly improved or resolved

- Three months for most other symptoms (fatigue often persists longer)

- Six months for all symptoms unless the patient had a complicated or prolonged admission to intensive care

In the absence of red flags, these timeframes can be used to guide follow-up, based on clinical judgement, with the proviso that patients schedule an appointment sooner if their condition deteriorates or they develop features that could mean referral or further investigation is required. Many regional HealthPathways recommend reviewing patients at 12 weeks if they are not improving with supported self-management.

The overall time to complete symptom resolution reported in the literature for patients with long COVID is highly variable. The largest meta-analysis currently available suggests that the average time to symptom resolution is four months in non-hospitalised patients with long COVID and nine months in those who required hospitalisation.9 However, in some cases symptoms can last significantly longer, with 15% of patients with long COVID continuing to experience symptoms at 12 months.9

Additional resources: