Published: 23 March 2022 | Updated: 27 February 2025

What's changed?

5 July 2023: updated evidence added to the chronic pain indication section

11 March 2023: updated information in the section on medicinal cannabis and driving

25 March 2022: theoretical estimate of lethal dose of THC in humans changed from 4 g to >15 g, supported by a difference reference

27 February 2025: updated information on approved medicinal cannabis products

If you would like to know what changes were made when the article was updated please contact us

Key practice points:

- The Medicinal Cannabis Scheme came into effect on 1 April, 2020 with the aim of improving access to medicinal cannabis

products by lifting regulatory barriers to prescribing. There are now two main pathways for prescribing medicinal cannabis:

- Medicinal cannabis products approved for distribution under the Medicines Act 1981 can be prescribed to any patient by an authorised prescriber*

for any indication within that prescriber's scope of practice. Medicinal cannabis products, that are controlled drugs (e.g. Sativex), require Ministerial approval to prescribe. All registered medical practitioners (i.e. doctors) have been granted Ministerial approval to prescribe Sativex without the need to submit an application to the Ministry of Health.

- Medicinal cannabis products that are not approved, but that are verified by the Medicinal Cannabis Agency

as meeting minimum quality standard, can be prescribed to any patient by a medical practitioner for any indication within

their scope of practice, without the need to seek approval to prescribe from the Ministry of Health. These prescriptions must be directly supplied to the patient by the prescribing medical practitioner, or dispensed via a pharmacy under Section 29 of the Medicines Act 1981.

- Approved medicinal cannabis products and products verified as meeting the minimum quality standard are listed at: the Ministry of Health website.

- Medical practitioners can still prescribe medicinal cannabis products that are neither Medsafe approved nor verified

by the Medicinal Cannabis Agency as meeting the minimum quality standard; however, these have no official New Zealand endorsement of efficacy, safety or quality, and there are more restrictive access requirements, particularly if the product meets the definition of being a controlled drug.

- No medicinal cannabis products are currently funded by PHARMAC

- Unapproved medicinal cannabis products and controlled drugs cannot be advertised to the public in any way (including

pricing information on websites). This restriction applies to any potential advertiser, e.g. suppliers,

wholesalers and healthcare practitioners.

- There is currently insufficient clinical trial evidence to support medicinal cannabis products being used first-line

for any indication. However, they may be suitable for some conditions if patients have ongoing symptoms

despite optimal use of conventional treatments or where other medicine use is contraindicated or

not tolerated.

- Healthcare professionals should familiarise themselves with the evidence (see links in document) regarding medicinal

cannabis as this will help guide informed discussions with patients about whether treatment is suitable, balancing the

safety and efficacy potential against individual patient characteristics and history

- If a decision is made to prescribe medicinal cannabis, an initial 4–12-week trial should be undertaken based on a detailed

treatment plan, including agreed upon objectives, and a plan for discontinuation if these are not achieved

- Ensure that the prescription is written by brand as the majority of medicinal cannabis products are unapproved medicines.

The brand selected should be the specific one researched during the decision-making process, as the quality, safety and efficacy may differ between products.

- Prescriptions for medicinal cannabis products that are either approved medicines (e.g. Sativex) or verified as meeting

the medicinal cannabis minimum quality standard can be dispensed at pharmacies much like other prescription medicines

* Section 2(1) of the Medicines Act 1981 defines an authorised prescriber as a nurse practitioner,

an optometrist, a medical practitioner, dentist, a registered midwife or a designated prescriber.

The unauthorised import, manufacturing and dealing of cannabis has been illegal in New Zealand since the implementation

of the Dangerous Drugs Act 1927.1 At the time, this law was enacted due to mounting international concerns

over illicit drug trafficking; however, there was a provision in the law that permitted cannabis to remain available as

a prescription medicine.1, 2 The New Zealand government passed further legislative restrictions over time to

broadly combat illicit drug supply and use, and cannabis was subsequently designated as a controlled drug under the Misuse

of Drugs Act 1975.1 These changes meant that medicinal cannabis could only be prescribed by a specialist with

Ministerial approval.1

Some people living in New Zealand self-medicate with cannabis regardless of the legal status

Cannabis consumption remains widespread in New Zealand, with 11–15% of adults reporting they had consumed it at least

once in the last 12 months.3, 4 Of these users, more than 40% reported that they self-medicate with cannabis

to treat pain or other conditions, rather than seeking guidance from a medical professional.3 This represents

a significant health issue as the quality and psychoactive content of illicitly procured cannabis can vary substantially,

putting the person at an increased risk of harm. It also potentially indicates they are not accessing conventional evidence-based

medicines and other treatments, further contributing to inequities in healthcare outcomes. Māori in particular have consistently

experienced higher rates of cannabis-related harm and prosecution compared with other ethnic groups.1

The shifting perspective on personal cannabis use

Public interest in pharmaceutical-grade medicinal cannabis heightened in New Zealand after several highly publicised cases

of people applying for access to cannabis products for treating conditions such as severe epilepsy, multiple sclerosis and

chronic pain. In late 2010, Sativex became the first available medicinal cannabis product with consent for distribution (approval)

under the Medicines Act 1981, and it could only be prescribed as an add-on treatment for patients with moderate to severe

spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis. Any prescribing of Sativex for off-label (unapproved) use – or prescribing

any unapproved medicinal cannabis products that were controlled drugs – required case-by-case Ministerial approval under

the previous regulations.

In recent years, amendments have been made to the Misuse of Drugs Act to reflect the shifting perspective that personal

drug use is a health issue rather than criminal.5 In 2018, changes were introduced to provide for a statutory

defence for the possession of illicit cannabis by terminally ill patients, and cannabidiol (CBD) products were reclassified

to no longer be controlled drugs (see: “The terminology associated with medicinal cannabis”).5 The following

year, further amendments were made requiring Police to exercise discretion in deciding when to prosecute for the possession

and use of controlled drugs.5 Although recreational cannabis use remains illegal, this approach shifts the

focus of prosecution towards individuals who profit from drug dealing, rather than users themselves. In addition, these

amendments were intended to be a first step in improving access to medicinal cannabis.5

On 1 April, 2020, the Misuse of Drugs (Medicinal Cannabis) Regulations 2019 came into force, enabling the implementation

of the Medicinal Cannabis Scheme (The Scheme).6 This provides a framework for a licenced domestic industry for

the cultivation, manufacture and supply of medicinal cannabis, and sets the minimum quality standard which all medicinal

cannabis products must meet. The Scheme is administered by the Medicinal Cannabis Agency (part of the Ministry of Health)

and aims to minimise barriers and improve patient access to quality medicinal cannabis products.6, 7 Any product

verified as meeting the minimum quality standard does not require further Ministerial approval to prescribe, even if it

is classified as being a controlled drug.

Evidence from other countries including Canada and The Netherlands show that government-led programmes to

control medicinal cannabis production and integrate use into the healthcare system can be beneficial.8 The introduction

of New Zealand’s Medicinal Cannabis Scheme:8, 9

- Permits evidence-based discussions with patients regarding the suitability and reasons for using medicinal cannabis

- Ensures product quality, consistency, and reduces the risk of product contamination

- Enables the monitoring of the patient’s response to treatment if prescribed, including both beneficial and adverse effects

- Allows New Zealand to meet its obligations under the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961; this includes establishing

an agency to control the commercial production and supply of cannabis for medical use, and reporting on the volumes of

production and manufacture to the International Narcotics Control Board

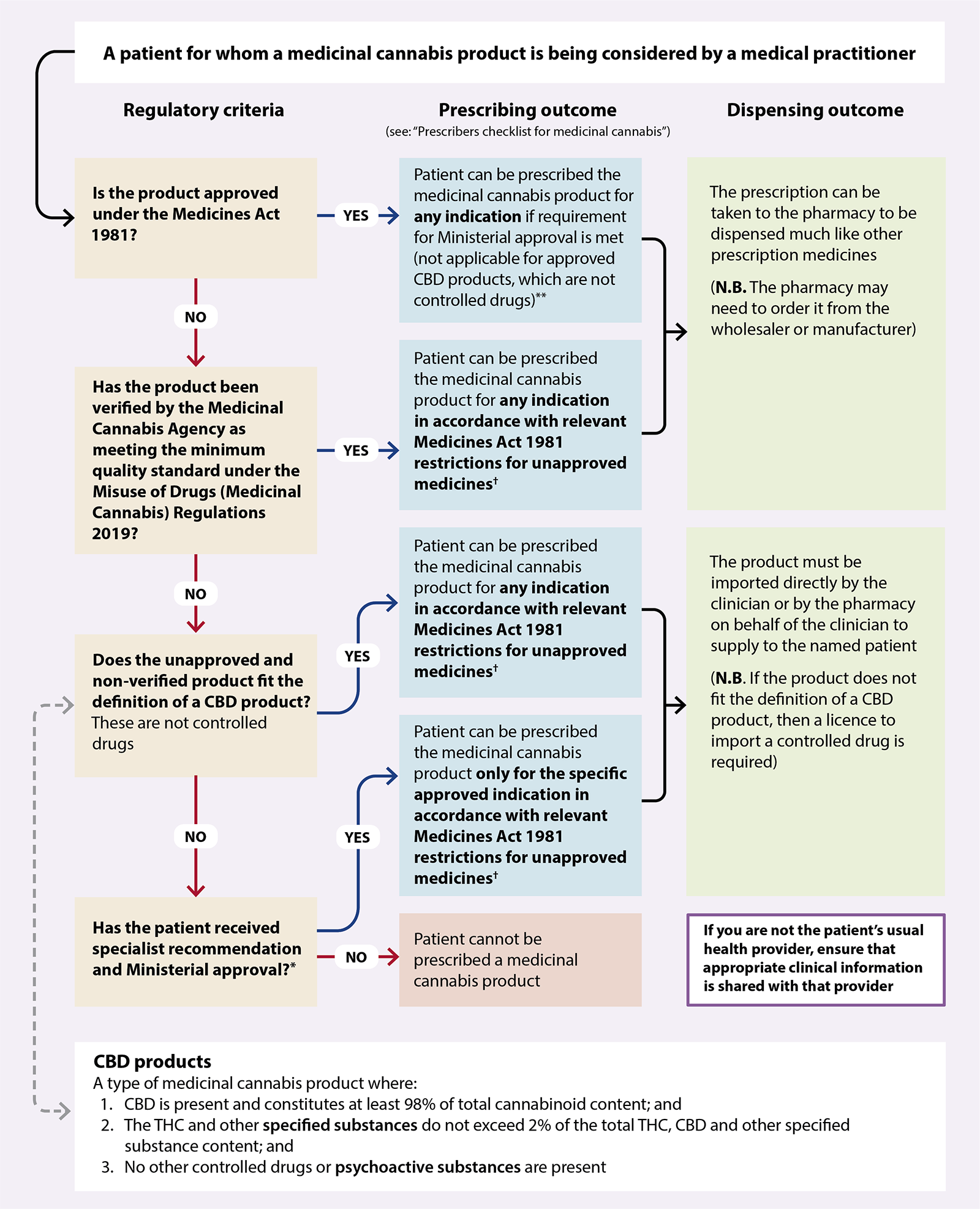

Summary of the Medicinal Cannabis Scheme: how does this affect prescribing?

With the implementation of the Medicinal Cannabis Scheme, medicinal cannabis products can now be prescribed

by a registered medical practitioner (i.e. doctor) to any patient under three main categories (Figure

1):6, 10

- Medicinal cannabis products that are approved medicines, i.e. with Medsafe approval (or provisional approval) can be prescribed by any authorised prescriber* for any indication within the prescriber's scope of practice. Medicinal cannabis products, that are controlled drugs (e.g. Sativex), require Ministerial approval to prescribe. All registered medical practitioners (i.e. doctors) have been granted Ministerial approval to prescribe Sativex without the need to submit an application to Ministry of Health. Approved medicinal cannabis products that are not controlled drugs (e.g. Epidyolex) do not require Ministerial approval to prescribe.

*Section 2(1) of the Medicines Act 1981 defines an authorised

prescriber as a nurse practitioner, an optometrist, a medical practitioner, dentist, a registered midwife or a designated

prescriber.

- Unapproved medicinal cannabis products verified as meeting the minimum quality standard by the Medicinal

Cannabis Agency can be prescribed to any patient by a medical practitioner for any indication within their

scope of practice, without the need to seek approval to prescribe from the Ministry of Health. These prescriptions must be directly supplied to the patient by the prescribing medical practitioner, or dispensed via a pharmacy under Section 29 of the Medicines Act 1981.

- Unapproved medicinal cannabis products NOT verified as meeting the minimum quality standard by the Medicinal

Cannabis Agency can still be prescribed by a medical practitioner and directly supplied to the patient by the prescribing medical practitioner or dispensed by pharmacy via Section 29 of Medicines Act. However,

unless the product fits the definition of being a CBD

product (see: “The terminology associated with

medicinal cannabis”) it is a controlled drug and subject

to corresponding restrictions under Regulation 22 of

the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 1977. Therefore, an

application for a named patient must first be approved

by the Minister of Health (delegated to the Ministry of

Health) for a specified indication prior to prescribing.

Prescribing by other types of registered prescribers

While it is anticipated that the majority of prescribing of

medicinal cannabis will be undertaken by medical practitioners

(i.e. doctors), medicinal cannabis products that are an approved

medicine and a controlled drug, e.g. Sativex, may be prescribed

in some instances by other registered prescribers, including:

- Nurse practitioners –

an application

to prescribe for a named patient must first be approved by the Minister of Health (delegated to the Ministry of Health). It can only be used

for the specified indication, and prescriptions can be for no more than a one-month supply.

- N.B. Designated nurse prescribers cannot prescribe medicines containing THC

- Designated pharmacist prescribers - an application to prescribe must first be approved by the Minister of Health (delegated to the Ministry of Health). THC is listed in Schedule 1B of the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 1977. Prescriptions can only be for a specified condition and the period of supply must be no longer than three days.11, 12

Only registered medical practitioners can prescribe unapproved medicines, even if verified as meeting the minimum quality

standard, because unapproved medicines must be supplied under Section 29 of the Medicines Act, and these prescriptions can

only be written by a doctor.13

The terminology associated with medicinal cannabis6

Marijuana – an alternative name for cannabis when it is used as a psychoactive substance; it usually

refers to the dried, crushed flowers and leaves. Other colloquial names include pot, dope and weed. In the international

medical literature, “marijuana” and “cannabis” are sometimes used interchangeably. However, when being used for treatment

of patients in the New Zealand healthcare setting, the term “medicinal cannabis” is preferred as it reduces the pre-conceived

association with recreational use.

Cannabinoid – a term describing a class of chemically related compounds capable of interacting with human

cannabinoid receptors (see: “The endocannabinoid system as a potential treatment target”).

Cannabinoids extracted from the cannabis plant are referred to as phytocannabinoids, however,

they can also naturally occur

in other plant species. Humans also produce their own endogenous cannabinoids (endocannabinoids).

The most notable phytocannabinoids are CBD and THC (see below), and much of the potential efficacy of medicinal

cannabis products depends on the synergetic effects between these compounds.15 There is little evidence regarding

the effects of other cannabinoids in humans, however, the majority are not psychoactive.

- Cannabidiol (CBD) – a non-intoxicating cannabinoid thought to modulate some of the psychoactive effects

of THC; it does not generally produce a “high” or have an intoxicating effect in isolation.

- Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) – the key psychoactive cannabinoid responsible for the “high” associated

with cannabis use, which is a sought-after effect for recreational users. THC is also associated with a wide range of other

effects, e.g. elevated heart rate, dizziness, impaired reaction time, reduced concentration and other neurological and

behavioural effects.

Medicinal cannabis/cannabinoid products – describes a manufactured product containing one or more cannabis-derived

ingredient(s) that is intended for therapeutic use. In New Zealand, this can include a dried cannabis product intended for

vaporisation (not smoking), or a product in a pharmaceutical dosage form (e.g. tablets, capsules, oils and oral mucosal

sprays) containing one or more cannabis-based ingredient(s) and no other prescription or controlled drugs. Food containing

cannabis is not permitted as a medicinal cannabis product. If the amount of THC or other specified

substances* is above a specific threshold, or if any other controlled drugs are present in the product (see:

“CBD products”), it is classified as a controlled drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975.

- CBD products – a subtype of medicinal cannabis product – sometimes referred to as a dosage product

or cannabis-based ingredient – where:

- CBD is present and constitutes at least 98% of total cannabinoid content; and

- The THC or other

specified

substances* do not exceed 2% of the total cannabinoid content

- No other controlled drugs or psychoactive substances are present

CBD products are not classified as a controlled drug.

CBD products are not classified as a controlled drug.

* “Specified substances” refers to a list of compounds that naturally occur in cannabis, capable

of inducing more than a minor psychoactive effect, by any means, in a person; THC is just one example. For further information

on what constitutes a specified substance, see Section 2A of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975. If you require clarification

as to whether a particular ingredient qualifies as a specified substance, email the Medicinal Cannabis Agency:

medicinalcannabis@health.govt.nz

N.B. For medical practitioners contemplating importing a

product, it is recommended that a certificate of analysis

is obtained from the manufacturer before importation to

check that the product meets the requirements relating

to specified substances (for further information on

importation, see: Access and dispensing considerations).

Figure 1. How the new regulatory framework affects the prescribing of medicinal cannabis

products by registered medical practitioners (i.e. doctors) in New Zealand.6

*An

application

form for Ministerial approval to prescribe non-pharmaceutical grade medicinal cannabis without consent for

distribution is available on the Ministry of Health website. The application must be completed by a specialist

who is managing the condition that the product is intended to treat or by the Chief Medical Officer of a District Health Board.

† Unapproved medicines must be prescribed by a medical practitioner, and directly supplied to the patient by the prescribing medical practitioner, or dispensed by a pharmacy via Section 29 of the Medicines Act.

**As of February, 2025, the only approved products are Sativex (CBD + THC) and Epidyolex (CBD). All registered medical practitioners (i.e. doctors) have been granted Ministerial approval to prescribe Sativex without the need to submit an application to the Ministry of Health.

The endocannabinoid system as a potential treatment target

The human endocannabinoid system (ECS) is comprised of endogenously produced cannabinoids, the enzymes affecting

their metabolism, as well as a widespread network of cannabinoid receptors, e.g. CB1 and CB2.16 CB1 receptors

are predominantly concentrated in the brain and central nervous system (CNS) but are also found in non-neural tissue, e.g.

the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, kidney and liver.16 CB2 receptors are found at a much lower level

than CB1 receptors in the CNS, and instead are mainly expressed in peripheral immune cells and tissues, and in

haematopoietic cells.16 Evidence from in vitro and animal-based studies has shown that binding of endocannabinoids,

phytocannabinoids (plant-derived) or synthetic cannabinoids to their corresponding receptors causes biological effects across

a range of functions, including:16

- The formation and storage of memory

- Neurological and cognitive development and function

- Sleep

- Mood

- Appetite and digestion

- Reproduction and fertility

- Inflammation and immunity

- Pain perception

- Cardiovascular system function

However, little is understood about how medicines affecting ECS-regulated processes actually influence disease

outcomes. The foundation of many arguments promoting medicinal cannabis involve extrapolating these laboratory

or animal-based findings, without substantiated evidence as to their translational effect on human-specific body system

dysfunction.

Meeting the minimum quality standard is not the same as being Medsafe approved

While these changes reduce barriers to accessing medicinal cannabis, and will likely result in increased patient interest

and demand, the minimum quality standard is not an endorsement of a product’s safety or efficacy, i.e.

it is not equivalent to being approved as a medicine by Medsafe. Instead, the standard recognises that a product is manufactured

according to strict good manufacturing practices and meets minimum standards of quality, which:14

While these changes reduce barriers to accessing medicinal cannabis, and will likely result in increased patient interest

and demand, the minimum quality standard is not an endorsement of a product’s safety or efficacy, i.e.

it is not equivalent to being approved as a medicine by Medsafe. Instead, the standard recognises that a product is manufactured

according to strict good manufacturing practices and meets minimum standards of quality, which:14

- Reduce the risk of harmful contaminants being present, e.g. pesticides and heavy metals, or any other ingredients that

pose a high risk of harm

- Ensure products contain the correct ingredients, are manufactured to the stated concentration, and that the concentration

is consistent throughout a batch

- Confirm that the product remains consistent throughout its stated shelf-life

- Ensure that the dosage form, packaging and labelling of products is appropriate and correct

Medsafe approval requires robust pharmacological data and human clinical trial results. Unless a medicinal cannabis product

obtains Medsafe approval, prescribers are the ‘gate-keepers’ to access for patients and must take responsibility and liability

for any outcome associated with prescribing an unapproved product. Therefore, it is important that healthcare providers

familiarise themselves with information regarding medicinal cannabis to help navigate discussions with patients, and to

ensure that informed clinical decisions are made (see: “Balancing the potential benefits and risks associated

with medicinal cannabis use”).

Prescribers of unapproved medicines should first obtain the patient’s informed consent, the details of which

should preferably be documented in their notes. This involves the patient understanding:

- That the medicine is not approved in New Zealand, i.e. it has not been assessed by Medsafe against regulations and standards;

it may be an approved medicine in other countries

- What, if any, other approved treatments are available

- The possible benefits in addition to any potential risks or adverse effects, including unknown risks

- That information about supply of their medicine will be forwarded to the medicine manufacturer or importer in New Zealand,

who will subsequently forward a subset of that information to Medsafe; this information will be recorded on a database

as a requirement of the Medicines Act

For more information on the medico-legal responsibilities and obligations associated with prescibing an unapproved

medicine, see: bpac.org.nz/bpj/2013/march/unapproved-medicines.aspx

Medicinal cannabis is not a first-line treatment for any indication

Given the recent changes in accessibility, some patients may incorrectly perceive medicinal cannabis products to be a

highly effective treatment that has only just been made available. However, despite numerous anecdotal reports from people

asserting that medicinal cannabis products are effective, the available pool of peer-reviewed clinical trials in humans

is limited, and the quality of evidence is not considered strong.17

Interpreting the significance of existing study outcomes is problematic due to:17, 18

- Potential bias

- Disproportionate enrolment of patients with a history of cannabis/cannabinoid consumption

- Differences in the dose, form and constituents of products between and within trials

- Small sample sizes and durations

- Heterogeneity in design

- A lack of effective blinding in randomised controlled trials (RCTs); nine out of ten patients or caregivers report being

able to identify when cannabinoids or placebo are being used

Therefore, in the absence of large and robust RCTs comparing medicinal cannabis with established treatments, medicinal

cannabis products cannot currently be considered a first-line option for any indication. However, trialling a medicinal

cannabis product may be suitable in some cases if (1) patients experience ongoing symptoms despite optimal dosing of available

evidence-based treatments, or (2) conventional treatments are contraindicated or not tolerated.

Shared and informed decision making is key

If conventional treatment options have been exhausted and a patient is interested in trialling a medicinal cannabis product,

then it can be jointly discussed during an informed decision-making session where:

-

The patient can convey what they understand about medicinal cannabis and why they are considering its use; any misconceptions

they may have regarding how it differs to illicit/recreational cannabis consumption or its benefits can then be addressed

-

The medical practitioner can set expectations by outlining any evidence of efficacy (or lack thereof) based on the indication

and safety implications; this information can then be compared against other medicines the patient has previously taken,

as well as any other pharmacological/non-pharmacological interventions that they may not have trialled yet

-

The appropriateness of medicinal cannabis use can be considered in the context of the patient’s medical history and

personal circumstances

This resource is not intended as a clinical guideline for medicinal cannabis use in New Zealand.

Regulators in other countries have critically evaluated existing literature and provided their own recommendations.

For further information on the evidence for medicinal cannabis use by indication, see:

For position statements from professional healthcare organisations, see:

Chronic pain. Chronic pain is the most common reason for patients enquiring about medicinal cannabis

or consuming illicit cannabis.19 Meta-analyses encompassing all types of chronic pain have yielded conflicting

results concerning pain improvement with medicinal cannabis.17–19 However, when assessed by pain subtype there

is low quality evidence that medicinal cannabis may improve perceived levels of pain in patients with chronic neuropathic

or malignant pain, or pain from other causes in a palliative care-setting.18 There is insufficient evidence to

support routine use in patients with other types of pain, e.g. acute pain or nociceptive pain associated with rheumatic

conditions (including osteoarthritis and back pain).18 There is also no evidence that adjunctive use of medicinal

cannabis reduces the use of opioids in patients with chronic non-malignant pain.19

Update: a 2023 Cochrane Systematic Review including 14 studies (N = 1,823) has demonstrated that oromucosal nabiximols (a type of cannabis extract containing both THC and CBD, e.g. Sativex) and THC alone medicinal cannabis products provide no clinically relevant benefit for patients with moderate-to-severe refractory cancer pain compared with placebo. These interventions also did not reduce sleep problems, or decrease the opioid maintenance and breakthrough doses required versus placebo. The number needed to treat (NNT) for patients to perceive a “much improved or very much improved” change in their symptoms with nabiximols was 16, while the number needed to harm (NNH) relating to nervous system adverse effects with nabiximols and THC products was nine. Dropout rates due to adverse effects and the frequency of psychiatric disorders were comparable across all treatment groups. It was also determined that use of CBD oil in patients with advanced cancer provides no additional benefit compared with standard palliative care alone for reducing pain, anxiety/depression or improving quality of life.

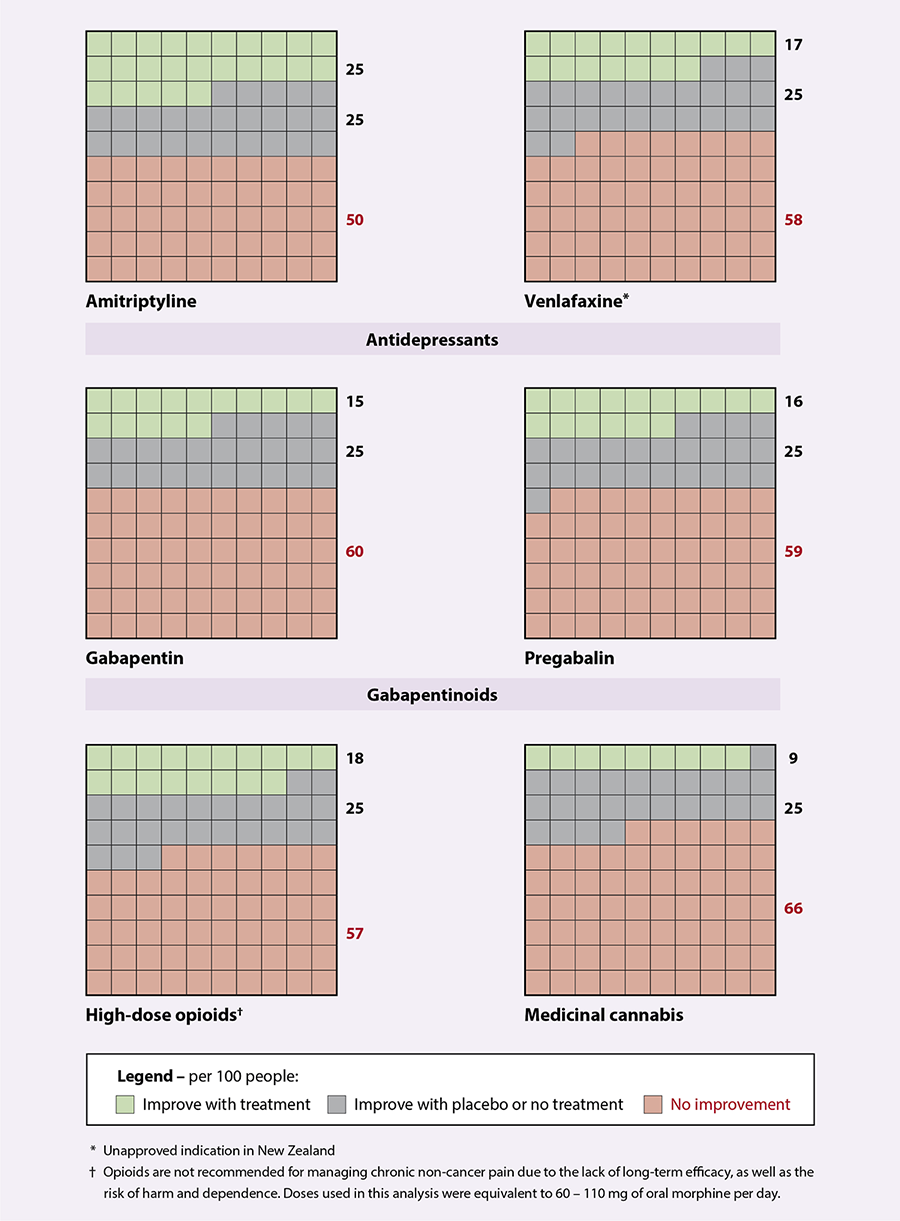

If medicinal cannabis is being considered for a patient with chronic neuropathic or malignant pain, it should

be prescribed as an adjunct after discussing and trialling other options which have greater evidence of efficacy and that

are funded (Figure 2). Canadian guidelines suggest medicinal cannabis should only be considered after trialling:18

- At least three other medicines if the patient has neuropathic pain

- At least two medicines if the patient has malignant pain

Figure 2. The efficacy of different pharmacological treatments for reducing chronic neuropathic pain by ≥30% over 4–12 weeks.

Adapted from Allen et al, 2018, which used indirect comparisons of data from Cochrane reviews of other neuropathic pain medications, in

combination with medicinal cannabis data from their own systematic review.18

Nausea and vomiting. There is evidence that medicinal cannabis may improve chemotherapy-induced nausea

and vomiting.20 However, many RCTs addressing this indication are several decades old, utilise comparator regimens

no longer in use, and involve a limited duration of patient follow-up (sometimes as little as 24 hours).20 There

is insufficient information available to support the use of medicinal cannabis for general nausea and vomiting.17

Practice point: while it is typically associated with recreational cannabis use, consumption

of products containing high levels of THC can also cause cyclic episodes of nausea and vomiting; a condition known as Cannabinoid

Hyperemesis Syndrome.21 This condition can be difficult to distinguish from other possible causes of nausea

and vomiting – and if it is not recognised – increases the risk of patients progressively self-escalating their cannabis

use, which then worsens the problem.21 As such, medicinal cannabis use should be discontinued if nausea and

vomiting persists following an initial trial (see: “Establishing a treatment plan”).

Spasticity. Medicinal cannabis use has consistently been associated with improvements in refractory spasticity

symptoms in patients with multiple sclerosis.17, 22 In New Zealand, Sativex is approved as an adjunct for moderate

to severe spasticity caused by multiple sclerosis.23 The THC content in Sativex is proposed to be the important

driver of efficacy for this indication through its interaction with cannabinoid receptors in the CNS.22, 23

Epilepsy. There is some evidence that CBD products may help reduce the number and severity of seizures

in young people with epilepsy, particularly those with Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.24 However,

CBD products should only be considered as an add-on treatment in refractory epilepsy, and the decision should be guided

by advice from a neurologist. Australian guidelines suggest that CBD products should only be trialled if four or five other

anti-epileptic medicines have been inadequate for seizure control, either alone or in various combinations.25

For children and adolescents with epilepsy, medicinal cannabis products should only

be prescribed by the specialist managing their condition.

For children and adolescents with epilepsy, medicinal cannabis products should only

be prescribed by the specialist managing their condition.

Other indications. Patients may also enquire about medicinal cannabis for other indications, however,

these should only be considered on a case-by-case basis if other conventional treatment options have been exhausted. There

is no compelling evidence from large clinical trials to suggest that medicinal cannabis is effective for treating the following

conditions: insomnia, glaucoma, anxiety or depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, movement

disorders (including tic disorder and Tourette’s syndrome), anorexia, cachexia, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, Alzheimer’s

disease or schizophrenia.26

A summary of the evidence by indication (including smaller clinical trial data) can be found in “The health

effects of cannabis and cannabinoids” by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, available at:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK423845/.27

High quality evidence into the short- and long-term safety of medicinal cannabis is lacking. Unless medicinal cannabis

products have received Medsafe approval (e.g. Sativex), they are not proven to meet international or New Zealand safety

standards.

Acute toxicity is highly unlikely

There is no known level of cannabinoid ingestion that will result in a toxic or lethal dose in humans.25 The median lethal dose of THC in animal models ranges from 800 to >9,000 mg/kg (depending on the species). Theoretical estimates of a lethal dose of THC for a 70 kg human range up to > 15 g.28

For CBD, doses of approximately 1,000 mg/kg have been tolerated in humans.

Practice point: recommend that patients keep medicinal cannabis products in a secure

location that children cannot easily access, e.g. a high or locked cupboard. Children are at an increased risk of adverse

effects due to their lower body weight, and little is known regarding the safety of consumption in children aged less than five years.

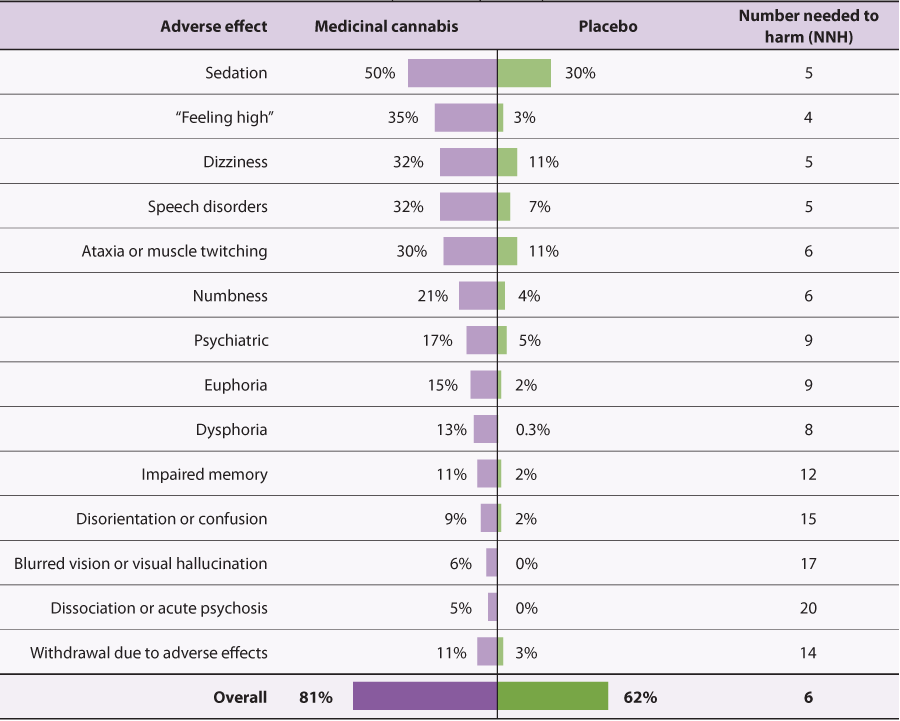

Adverse effects are common but may be tolerable depending on the patient and the formulation

Overall, RCTs show that four out of five people taking a medicinal cannabis product experience some form of adverse effect.18 While

direct evidence from head-to-head clinical trials is lacking, CBD products are anecdotally considered to have an improved

safety profile compared with products that have a higher level of THC content, and are unlikely to induce short-term psychoactive

effects, e.g. euphoria.25

Common adverse effects. When initiating use or increasing the dose of any medicinal cannabis product,

patients may experience transient adverse effects such as nausea, appetite changes, hypotension, gastrointestinal upset,

diarrhoea and a dry mouth.25 In RCTs of medicinal cannabis use, many of the reported adverse effects are mild

and may be tolerable if anticipated.18

Neurological and behavioural adverse effects. The risk of more severe neurological and cognitive effects

should also be a focus of any decision-making discussion with a patient (Table 1). For example, in a

systematic analysis that mostly included THC-dominant or balanced medicinal cannabis formulations (i.e. not CBD products),

the number needed to harm for dissociation or acute psychosis with medicinal cannabis is estimated to be 20.18 While

patient reports of “feeling high” are generally associated with the use of products that have higher THC content, CBD products

can still cause undesirable neurological and behavioural changes, and further investigation is required to distinguish the

comparative risk.18 There is an association between the use of botanical and synthetic cannabis and long-term

psychosis.29 It should be emphasised that the long-term safety implications of medicinal cannabis use is uncertain;

safety data from clinical trials of medicinal CBD are relatively reassuring, however, these generally come from small cohorts

studied for short durations.

Reporting adverse effects associated with the use of medicinal cannabis products

is important to further expand the understanding of their safety, particularly given the low quality of clinical trial

data available to date. Any suspected adverse effects can be report to the Centre for Adverse Reactions Monitoring (CARM)

at: nzphvc.otago.ac.nz/reporting/#ReportSideEffects.

Table 1. Event rates of neurologic and cognitive adverse effects reported in randomised controlled trials for medicinal cannabis versus placebo.

Adapted from Allen et al, 2018, which included pooled results from analyses using various THC:CBD ratios, many of which were THC-dominant

or balanced formulations (i.e. not CBD products).18

Before making a decision to prescribe a medicinal cannabis product, the patient’s history should be reviewed as this may

influence the suitability of treatment.

Medicinal cannabis is generally not appropriate in people:25

- Who

are pregnant, planning on becoming pregnant, or breastfeeding; pre-term labour and low birth weight have

been reported, and cannabinoids can enter breast milk

- With

a history of psychiatric disorders (particularly schizophrenia), mood or anxiety

disorder; Sativex is contraindicated in people with a personal or family history of psychosis or a history of

another severe psychiatric disorder.30 N.B. Depending on the severity of the mental illness

and the reason for prescribing medicinal cannabis, there may be some occasions where the potential benefit is considered

to outweigh the risk, e.g. in palliative medicine medicinal cannabis may be considered in a person with anxiety disorder,

introduced in a controlled manner.

-

Who have unstable cardiovascular or cardiopulmonary disease

-

With

a history of hypersensitivity to any component used in the manufacturing of the medicinal cannabis product,

e.g. sesame oil, peppermint oil

Situations where caution is warranted

Hepatic or renal impairment. Cannabinoids are primarily cleared by the liver and therefore moderate to

severe dysfunction will likely increase the risk of adverse effects.25 Although renal function is not thought

to affect clearance in healthy adults, medicinal cannabis products should be taken at the lowest effective dose in patients

with chronic kidney disease.31 In addition, if the patient will potentially require dialysis or a kidney transplant

in the future, it is important to check with their nephrologist whether medicinal cannabis use is appropriate before prescribing.31

Children or adolescents. Medicinal cannabis products should typically be avoided in patients aged under

18 years due to a lack of safety and efficacy data, and uncertainty regarding the possible effects on the developing brain.

There are some situations where use of medicinal cannabis may be considered in a young person, e.g. for epilepsy, but it

should only be prescribed by a specialist clinician who is involved in the care of the patient for the condition being treated.

History of falls. Little is known about medicinal cannabis use in elderly or frail patients. Given that

cannabinoids can decrease blood pressure and cause sedation and dizziness, this may increase the risk of falls.18,

25 If a medicinal cannabis product is being considered for such patients, then their home environment and level of

caregiver support should be considered. If a decision is made to prescribe, treatment should be commenced at a very low

dose and increased slowly.25

Previous risk-associated behaviours, e.g. substance misuse disorder and drug dependence (including heavy

alcohol use). Although these behaviours are not a contraindication for medicinal cannabis use per se, identifying them may

(1) help shape the discussion around the intentions of seeking this type of treatment, and (2) highlight the need for safeguards

to prevent excessive dosing or reliance on a product if it does not help the patient meet treatment objectives.25

Psychosocial support considerations. Given that medicinal cannabis consumption can potentially cause

neurological and cognitive impairment, consideration should be given to the patient’s home-setting; both whether they have

people to support them when initially trialling the product, and whether they have children or other dependents that may

also be affected by their use, e.g. if the product causes dissociation, somnolence or acute psychosis.

Financial position. Medicinal cannabis products are not funded, and currently available options may be

unaffordable for many patients. Cost may therefore result in barriers and inequitable access; for example, products may

be too expensive for some patients to initially trial, or the financial burden of repeat prescriptions may be a barrier

to ongoing use. This also leads to concerns that patients may seek treatment using illicit cannabis of unknown constituents

and strengths.

Therefore, key concepts about cost to discuss during an informed decision-making discussion include:

- “Is there the potential for financial harm or difficulty?”

- “Would the patient be going without something necessary to afford treatment?”

- “Is there a funded medicine that has not been trialled which might be more suitable?”

- “Is the patient aware of the added risks associated with switching to illicit cannabis use if they find repeat prescriptions

of legal medicinal cannabis to be too expensive?”

As competition associated with domestic cultivation, manufacturing and supply increases under the new Medicinal Cannabis

Scheme, the average cost of products is expected to decrease over time. However, it is difficult to predict when this shift

will occur, and whether the magnitude in price difference will make ongoing medicinal cannabis use any more realistic to

those experiencing financial hardship.

Employment. The patient’s employment type should be considered during discussions, especially where driving

or operation of heavy machinery is involved.25 An important question to consider is: “will possible adverse

effects associated with medicinal cannabis use, such as sedation, compromise their safety – or the safety of others – in

the workplace?”. Employment New Zealand outlines that employers have a responsibility to create a safe work environment

and “should provide employees with the highest level of protection from risks as is reasonably practicable. A risk includes

dangerous behaviour resulting from drug or alcohol use”.32 However, it is unlikely that medicinal cannabis

use has been considered in the development of current health and safety procedures for most workplaces.

Practice point: patients should be advised not to work until it is clear how the medicinal cannabis product

affects them. However, if this is not feasible, or if there is doubt about the suitability of medicinal cannabis due to

a patient’s employment type, a pragmatic approach would be to offer to write a letter to the patient’s employer (with the

patient’s consent) to open dialogue with them and to ensure the process is transparent.

Driving. It is illegal to drive while impaired, so depending on the type of medicinal cannabis

product and the patient’s response to treatment, driving is not advised.33 Patients initiating use of a medicinal

cannabis product should refrain from driving until it is clear how the product affects them; THC is more likely to impair

cognitive function, while CBD products are generally considered to have a quantity of THC that is unlikely to cause impairment.34 In

New Zealand, people who fail a compulsory impairment test during roadside testing are required to undergo a blood test.33

THC is listed as one of the drugs being tested for under the Land Transport (Drug Driving) Amendment Act 2022 (CBD is not listed).35

The "tolerance blood concentration" for THC is 1 ng/ml and the "high-risk blood concentration" is 3 ng/ml.35

This legislation also allows for oral fluid testing to be used as part of roadside testing, however, as of May 2023 NZ Police have not yet identified an appropriate device that meets the criteria required for approval.33 A medical defence may be available to drivers if they:33, 35

- Have a current legal prescription for the medicinal cannabis product

- Have complied with the instructions from the prescriber or from the manufacturer of the product about driving, consuming

alcohol or other prescription medicines (or both) while consuming the product

For further information relating to:

Drug testing. In addition to roadside driver testing, patients may undergo drug testing for a variety

of other reasons, e.g. workplace screening or competitive sports; depending on the setting, product and type of test or

testing kit, medicinal cannabis use may result in a positive test. Products containing a higher THC content are much more

likely to be detected with drug testing, particularly if a urine-based test is used.36 THC can progressively accumulate

in fatty tissues and slowly redistribute over time, meaning it may be detectable for days to weeks after use.37 CBD

products will generally not be detected using traditional testing methods.32 Cannabinoids are a prohibited substance

in competition for most sports and therefore athletes should be made aware of this during initial discussions.

Consider current medicine use

Interactions between medicinal cannabis products and other medicines are possible. Both THC and CBD are inhibitors of

CYP450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of numerous psychotropic medicines.38 Medicines that are prominent

substrates for CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 can have altered activity when used with cannabinoids, and close monitoring

is required if they are prescribed concomitantly.38 For example, the anti-epileptic clobazam is converted by

CYP2C19 into an inactive metabolite, however, CBD-mediated inhibition of CYP2C19 substantially increases clobazam plasma

concentrations.37 It has been suggested that this interaction may account for the CBD-associated decrease in

seizure frequency observed in randomised controlled trials of children with refractory epilepsy.37

Other examples of medicines that may interact with cannabinoids include rifampicin, fluoxetine and warfarin.38 Medicinal

cannabis products may also reduce the effectiveness of systemic hormonal contraceptives, although the evidence is inconclusive.23,

38 Until further evidence is available, women taking a hormonal contraceptive should consider using an additional

barrier contraceptive while taking a medicinal cannabis product, and continue use for three months after discontinuing the

product.23

The New Zealand Formulary (NZF) interaction checker can be used to assess whether a patient’s current medicines

have potential interactions with CBD alone, CBD + THC or marijuana (Cannabis sativa). For further information,

see: https://nzf.org.nz/nzf_1.

If a decision is made to trial medicinal cannabis, all current and future products that are either Medsafe approved or

that are verified as meeting the minimum quality standard will be listed

on the Ministry of Health website. Pathways exist to prescribe products that are neither Medsafe approved

nor verified as meeting the minimum quality standard, but they have more restrictive access criteria (see: Figure

1 and “Access and dispensing considerations”).

The advertising of unapproved medicinal cannabis products and controlled drugs to the public is not permitted; this restriction

applies to anyone, including advertising by suppliers, wholesalers and healthcare practitioners. Competition is expected

to decrease prices over time, particularly once more domestic products become available. For pricing or other product details,

contact the manufacturer or wholesaler directly.

CBD products can be prescribed for up to a three-month supply, while any medicinal cannabis product containing enough

THC or other specified substances to be classified as a controlled drug can only be prescribed for up to a one-month supply.6 With

the exception of the Sativex and Epidyolex datasheets,

there are no official New Zealand guidelines available to assist the selection of medicinal cannabis doses or formulations

for specific indications. Prescribers can follow manufacturers recommendations.

Prescriber's checklist for medicinal cannabis products

For a patient to be dispensed a medicinal cannabis product, including CBD products, they need to have a valid prescription

from a medical practitioner. The prescription must:6

-

Be handwritten on a controlled drug prescription form (except for CBD products as they are not classified as controlled

drugs), or on a personally signed barcoded controlled drug ePrescription

-

Specify the brand and prohibit any generic substitutions; in some cases, prescribing software may automatically enable

generic substitutions by default, so particular care should be taken to disable or remove this option if present

-

Not be for a product in a form intended for smoking

-

Not be for a product meeting the definition of “food” under the

Food Act 2014

-

Not be for a product in a sterile dosage form, e.g. eye drops

-

Be prescribed for supply under Section 29 of the Medicines Act if the product is not Medsafe approved, after gaining

and recording patient consent

-

Be for no more than a one-month supply if a controlled drug (including Sativex)

-

Be for no more than a three-month supply if a CBD product

Factors that may influence product selection

Route of administration. The route of administration for medicinal cannabis affects cannabinoid

bioavailability and the onset of action: 37

- Oral route (e.g. oral liquid, capsule or tea) – the slowest and most variable route of absorption. Oral

administration is associated with a low-level of bioavailability (~10–20%) due to intestinal and hepatic first-pass metabolism.

Effects typically occur progressively, peak two to four hours following consumption and can last for 6–24 hours; this extended

duration of effect might be more desirable for patients seeking symptom control over longer periods of time, e.g. chronic

pain.

- Oral mucosal (e.g. spray) – although it is assumed some of the product will be swallowed, this route

may increase bioavailability through direct absorption through the oral mucosa. Effects likely peak after 90–120 minutes

and last for a comparable amount of time to orally administered products.

- Vaporisation (e.g. oil or dried flower) – the most rapid onset of action, with maximum plasma concentration

peaks within minutes following inhalation. Effects may reach a maximum after 15–30 minutes, and last 2–4 hours. Vaporisers

can be imported and sold only if they have been approved as a medical device by an overseas regulator. Other cannabis vaporiser

devices, and non-regulated utensils with prohibited

features, continue to be prohibited from New Zealand and may be confiscated by Customs.

- Topical (e.g. patches and gels) – most topical formulations produced overseas are CBD-based as CBD

is approximately ten times more permeable through the skin than THC. The onset and duration of action is difficult to predict

and varies substantially between patients.

Different routes of administration

are associated with distinct risk profiles. When a medicinal cannabis product is verified as meeting the minimum quality

standard for a specified route of administration, it only meets the standard for that particular route, i.e. a separate

assessment would need to be undertaken for a product to be verified for use via other routes. If a medical practitioner

wants to prescribe a medicinal cannabis product to a patient for use via an unverified route of administration, it is the

prescriber’s responsibility to consider the risks of using a product in a way it was not designed to be used against any

potential benefits. For example, if an oral solution was verified for use via the oral route of administration but was

being considered for use via the vaporisation route, considerations include:

Different routes of administration

are associated with distinct risk profiles. When a medicinal cannabis product is verified as meeting the minimum quality

standard for a specified route of administration, it only meets the standard for that particular route, i.e. a separate

assessment would need to be undertaken for a product to be verified for use via other routes. If a medical practitioner

wants to prescribe a medicinal cannabis product to a patient for use via an unverified route of administration, it is the

prescriber’s responsibility to consider the risks of using a product in a way it was not designed to be used against any

potential benefits. For example, if an oral solution was verified for use via the oral route of administration but was

being considered for use via the vaporisation route, considerations include:

- Whether there is any evidence the excipients in the oral liquid product are safe to be vaporised and inhaled, and whether

toxic by-products may be created during heating of a product designed to be consumed as an oral formulation. Many oral

liquid medicinal cannabis products contain a carrier oil which is not intended for vaporisation, e.g. coconut oil. Products

may also contain an antioxidant, e.g. vitamin E.

- The microbial contamination testing limits for products intended for vapourisation are stricter than limits applied to oral products due to increased risks with the inhaled route of administration.

For further information about the obligations of a prescriber for prescribing unapproved medicines, see:

www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/RIss/unapp.asp

The THC:CBD ratio. The label on medicinal cannabis products that have been verified against the minimum

quality standard must clearly detail the THC and CBD content (including derivatives), as well as any other ingredient derived

from cannabis whose content is at least 1% of the total weight or volume. THC and CBD are associated with different effects,

and depending on the ratio may influence each other’s biological activity.40 Although there are anecdotal reports

that certain THC:CBD ratios are more effective for specific indications (e.g. it is thought that THC content is necessary

for antispastic, antidystonic and anti-tic efficacy), there is currently insufficient clinical trial evidence in humans

to establish firm recommendations.40 Australian guidelines suggest that products with low/minimal THC content

are more suitable when psychoactive effects are undesirable.25

Establishing a treatment plan

Once a product has been selected, establishing a treatment plan with the patient is essential to assess its

effectiveness and safety, including:25, 39

- Treatment objectives – clearly document the target symptom(s) and how any improvement(s) will be assessed.

For example, this may be a metric improvement in a pain score or symptom algorithm (e.g. 30%), or an objectively measured

goal such as being able to perform a daily task that they were previously unable to.

- Timeframe – an initial one-month trial period is likely suitable to establish benefit and adverse effects.

Use of the medicinal cannabis product should stop if the desired effect is not obtained after 4–12 weeks.

- Dosing – a good rule-of-thumb is “start low, go slow”. The exact starting dose and titration

schedule will depend on the particular product, the balance of THC:CBD content, and patient specific characteristics. Patients

taking a medicinal cannabis product for the first time without a history of previous cannabis use should start with a very

low dose and cease use if they experience adverse effects. Increasing the dose weekly is a pragmatic strategy unless the

manufacturer instructions or Medicine datasheet specify otherwise (e.g. see the

Sativex

datasheet for further information). Dosing in the evening may be preferable for formulations with higher THC content.

More specific guidance on dosing is available in the international literature,39 however, caution should be

taken when applying these recommendations in clinical practice.

- Risk management strategies – safeguards should be established. For example, if there are concerns over

the potential for misuse, then dispensing frequency restrictions should be considered, and the prescriber should remain

vigilant for other drug seeking behaviours, e.g. early requests for repeat prescriptions, claims of lost prescriptions,

or requests for dose increases.

- Monitoring – clinical review should occur more frequently at first and then less frequently if the

product is tolerated and stable dosing is established (based on clinical judgement). At each review, consider whether any

functional and quality of life improvements outweigh reported adverse effects, and whether the patient is exhibiting undesirable

behavioural or cognitive changes. There are no specific blood testing requirements. However, baseline liver function tests

should usually be performed.

- Discontinuation plan – outline a strategy for discontinuing use if the treatment objectives are not

met, e.g. a dose reduction schedule or immediate treatment cessation.

Access and dispensing considerations

As outlined in Figure 1, the Medicinal Cannabis Scheme means that if a medicinal cannabis product is a Medsafe

approved medicine (e.g. Sativex, Epidyolex) or verified as meeting the Medicinal Cannabis Agency minimum quality standard, then prescriptions

can be taken to any pharmacy for dispensing. Pharmacists can then dispense the product from existing stock (if available),

or obtain the product from a wholesaler or the manufacturer.6

Accessing medicinal cannabis products that do not have Medsafe approval or Medicinal Cannabis Agency verification against

the quality standards

There are still pathways for prescribing unapproved medicinal cannabis products that have not been verified as meeting

the minimum quality standard by the Medicinal Cannabis Agency under the new regulations (Figure 1).

However, if such a product is selected, it should be clearly conveyed to the patient that it lacks a New Zealand-specific

verification of efficacy, safety or quality, and the responsibility for any outcome(s) lies with the prescriber. As such,

these products should generally not be a first choice if there are other suitable options available.

If a CBD product is selected that does not meet the minimum quality standard or has not yet been assessed

against the standards, then it can still be prescribed by a registered medical practitioner (i.e. doctor) for any indication

within the scope of their practice, but it must be imported directly in an amount required for the named patient by the

medical practitioner or a pharmacy on behalf of the registered medical practitioner.6 Having an expectation of future prescriptions is not considered to be a reasonable excuse to import medicinal cannabis products that have not been verified against the minimum quality standard. Given that CBD products are not controlled drugs, no additional licences are required by the medical practitioner or pharmacist. Particular care should be taken when sourcing unverified CBD products

from overseas manufacturers as they may have higher THC content than is permitted under New Zealand legislation. A certificate

of analysis is required from the manufacturer to confirm that the product meets the definition of being a CBD product; this

should be checked by the prescriber before placing the order, and accompany the imported product to assist New Zealand border

officials in their assessment.41

For other medicinal cannabis products (excluding CBD products) that do not meet the minimum quality standard

or have not yet been assessed against the standards,

Ministry

of Health approval is required and they can only be used for the specified indication.6 In addition, a licence

to import controlled drugs is required for each consignment, issued by Medsafe (for further information,

email

Medicines Control).6 The product must be imported directly in an amount required for the named patient by

the registered medical practitioner (i.e. doctor) or a pharmacy on behalf of the registered medical practitioner.