Published: July, 2023 | Review date: July, 2026

This audit identifies patients who present with winter illnesses

and documents their management so that clinicians can reflect

on their practice with the overall aim of reducing inappropriate

prescribing of antibiotics in primary care, and therefore

addressing the threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Over the winter months, thousands of people across New

Zealand will present to primary care with winter illnesses, i.e.

sore ears and throats, nasal and sinus congestion, coughs

and colds.* The COVID-19 pandemic has added another layer

of complexity to the management of patients with these

symptoms. Many winter illness symptoms are caused by

viral infections and antibiotic treatment is not appropriate.

In some cases, there may be bacterial infection present but

the infection will be self-limiting and the adverse effects of

antibiotics may outweigh potential benefits

There will be, however, some scenarios in which antibiotics

are appropriate. In general, antibiotic treatment for winter

illnesses should be considered in patients who have a

known or likely bacterial infection and are at increased risk

of developing systemic complications; this includes those

who are systemically very unwell, young infants, frail or older

people, or those who have co-morbidities, e.g. immune

suppression, diabetes or significant heart, lung, renal, liver

or neuromuscular disease. Also, people with a history of

hospitalisations and children of premature birth are often at

increased risk of developing systemic complications. People

with certain specific infections generally require antibiotics,

e.g. pneumonia, pertussis, or acute otitis media or sore throat

in some groups.

For most people with upper respiratory tract infections,

symptomatic treatment will offer better outcomes than

antibiotics (which will not be indicated in most cases).

Providing patients or caregivers with clear information about

when antibiotics are appropriate, supportive treatments

and the expected duration of symptoms can help reduce

unnecessary antibiotic use over the winter period.

Refer to the bpacnz antibiotics guide for indications

for antibiotic treatment for common winter illnesses:

bpac.org.nz/antibiotics/guide.aspx

* For the purposes of this audit, this group of symptoms will be referred

to as “winter illnesses”, but it is acknowledged that these illnesses

occur at any time of the year

Summary

Ideally, antibiotics for winter illnesses should only be

prescribed for patients with a known or likely bacterial

infection, and for those who are at increased risk of developing

systemic complications. There are also other specific

conditions and clinical circumstances where antibiotics are

indicated, e.g. pneumonia, pertussis and some groups with

sore throat, acute otitis media or sinus symptoms.

For each patient who presents with a winter illness, review

their notes and record the following information:

- The likely diagnosis

- Whether an antibiotic was indicated, based on a likely

diagnosis of a bacterial infection and the patients

individual clinical circumstances

- What treatment was provided: if advice on symptomatic

treatment only was given (no antibiotic), an antibiotic

was prescribed or a “back-pocket” prescription was

given. Also record if the patient returned for a followup visit and if so what action was then required, e.g.

different diagnosis, prescription for antibiotic, referral.

Recommended audit standards

For patients presenting with symptoms consistent with a

common winter illness the clinical notes should reflect the

likely diagnosis and document what treatment was offered

and why. For most people with winter illnesses supportive

treatment options such as paracetamol, decongestants,

adequate fluid intake and rest will provide the best

symptomatic relief.

Eligible patients

All patients who present with symptoms of a winter illness are eligible for this audit.

Identifying patients

Searching for eligible patients electronically through your

PMS will not easily work for this audit given that multiple

search terms would be required. Therefore, the simplest

way to identify eligible patients is to keep a tally of those

who present with a winter illness as you go through your

consulting sessions over a week or two, until sufficient

numbers of patients have been seen. Exclude patients who

tested positive for COVID-19 or were referred to hospital for

treatment at the initial consultation.

Sample size

The number of eligible patients will vary according to your

practice demographic and the circulating winter illnesses at

the time of the audit. A sample size of 20 – 30 patients is

sufficient for the purposes of this audit.

Criteria for a positive outcome

A positive result is if:

- An antibiotic was not indicated and advice on symptomatic treatment only was given

- An antibiotic was indicated and prescribed or a “back pocket” prescription given

Data analysis

For each patient presenting with a winter illness, record if

a diagnosis was made, whether an antibiotic was clinically

justified and what treatment was provided.

For example, if a patient presented with symptoms

consistent with a viral winter illness, and there were no other

complicating factors, then an antibiotic is not indicated

and if an antibiotic was not prescribed, this is a positive

result. If a patient presented with otitis media and they had

complicating factors, e.g. aged under six months, then an

antibiotic is indicated, and if an antibiotic was prescribed, this

is also a positive result.

The purpose of collecting data on follow-up consultations

is for reflection on practice: did the diagnosis change? Is an

antibiotic now indicated?

Clinical audits can be an important tool to identify where gaps exist between expected and actual performance. Once completed, they can provide ideas on how to change practice and improve patient outcomes. General practitioners are encouraged to discuss the suitability and relevance of their proposed audit with their practice or peer group prior to commencement to ensure the relevance of the audit. Outcomes of the audit should also be discussed with the practice or peer group; this may be recorded as a learning activity reflection if suitable.

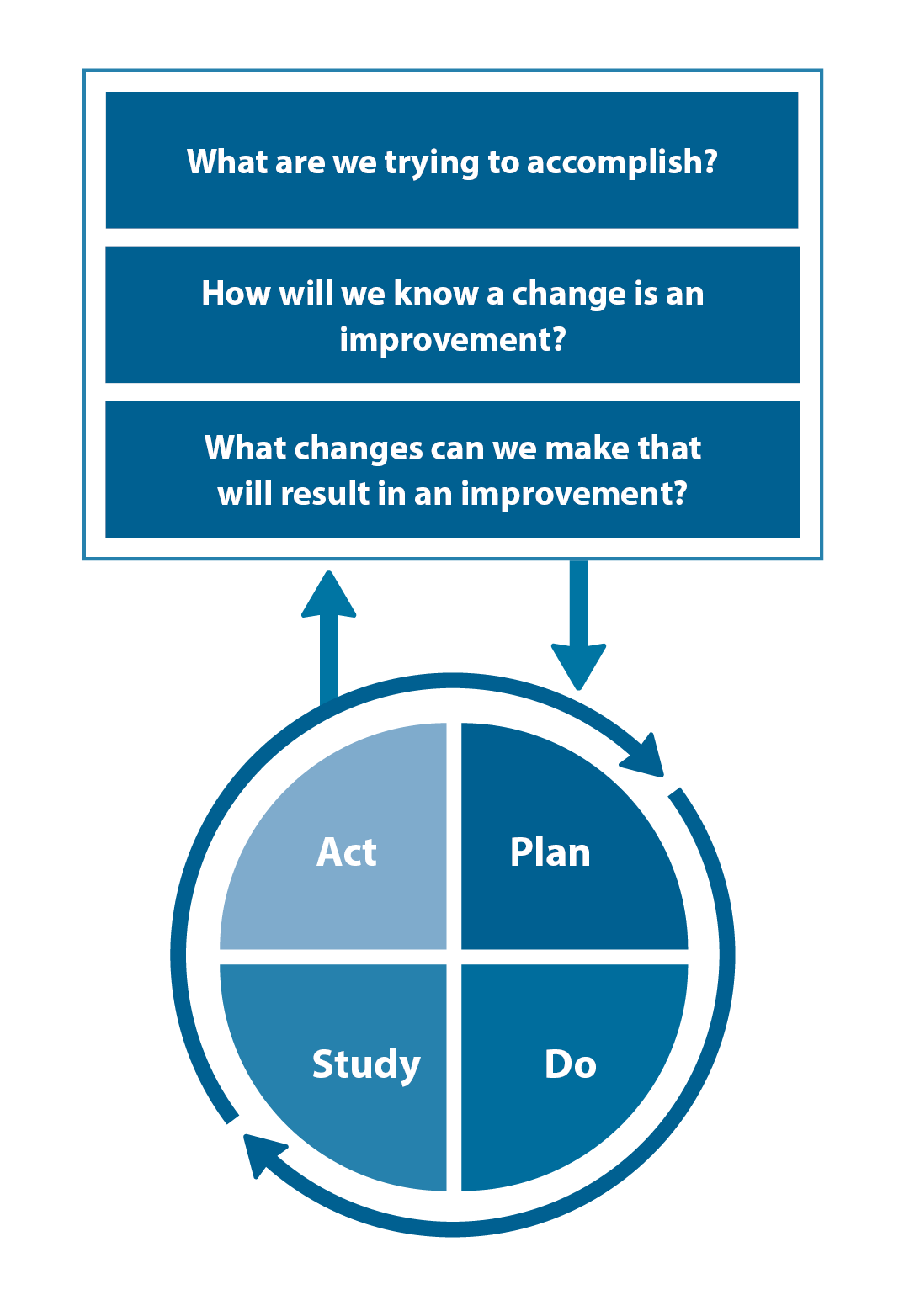

The Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) model is recommended by the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners (RNZCGP) as a framework for assessing whether a clinical audit is relevant to your practice. This model has been widely used in healthcare settings since 2000. It consists of two parts, the framework and the PDSA cycle itself, as shown in Figure 1.

1. The framework

This consists of three questions that help define the “what” and “how” of an improvement project (in this case an audit).

The questions are:

- "What are we trying to accomplish?" – the aim

- "How will we know that a change is an improvement?" – what measures of success will be used?

- "What changes can we make that will result in improvement?" – the concept to be tested

2. The PDSA cycle

This is often referred to as the “engine” for creating, testing and carrying out the proposed changes. More than one cycle is usually required; each one is intended to be short, rapid and frequent, with the results used to inform and refine the next. This allows an ongoing process of continuous learning and improvement.

Each PDSA cycle includes four stages:

- Plan – decide what the change to be tested is and how this will be done

- Do – carry out the plan and collect the data

- Study – analyse the data, assess the impact of the change and reflect on what was learned

- Act – plan the next cycle or implement the changes from your plan

Figure 1. The PDSA model for improvement.

Source: Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycles and the model for improvement

Claiming credits for Te Whanake CPD programme requirements

Practice or clinical audits are useful tools for improving clinical practice and credits can be claimed towards the Patient Outcomes (Improving Patient Care and Health Outcomes) learning category of the Te Whanake CPD programme, on a two credit per learning hour basis. A minimum of 12 credits is required in the Patient Outcomes category over a triennium (three years).

Any data driven activity that assesses the outcomes and quality of general practice work can be used to gain credits in the Patient Outcomes learning category. Under the refreshed Te Whanake CPD programme, audits are not compulsory and the RNZCGP also no longer requires that clinical audits are approved prior to use. The college recommends the PDSA format for developing and checking the relevance of a clinical audit.

To claim points go to the RNZCGP website: www.rnzcgp.org.nz

If a clinical audit is completed as part of Te Whanake requirements, the RNZCGP continues to encourage that evidence of participation in the audit be attached to your recorded activity. Evidence can include:

- A summary of the data collected

- An Audit of Medical Practice (CQI) Activity summary sheet (Appendix 1 in this audit or available on the

RNZCGP website).

N.B. Audits can also be completed by other health professionals working in primary care (particularly prescribers), if relevant. Check with your accrediting authority as to documentation requirements.