Published: June, 2025 | Review date: June, 2028

This audit helps healthcare professionals identify whether laboratory requests for microscopy, culture and sensitivity analysis of urine samples (urinalysis) were clinically appropriate in adult patients with a suspected urinary tract infection (UTI). Laboratory urinalysis is not required in most adult patients with an uncomplicated lower UTI as it is unlikely to affect treatment decisions.

UTIs are a common reason for antibiotic prescribing in New Zealand. The lower urinary tract is most often affected due to bacteria, usually from the gastrointestinal tract, entering the urethra and proliferating in the bladder. In many cases, the isolate causing the infection is highly predictable: 70 – 95% result from Escherichia coli. Other causative species include Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Klebsiella spp., Enterococcus spp. and Proteus spp. Many complicated UTIs are also caused by E. coli, however, the range of possible causative species is much broader than for uncomplicated infections. Although rare in the community, complicated UTIs can occur as the result of fungal infection, which is generally associated with Candida spp., e.g. in people with an indwelling catheter.

Uncomplicated UTIs can be diagnosed with a high level of confidence in patients with a focused history of lower urinary tract symptoms in the absence of complicating factors or red flags. Subtle or atypical presentations are possible, however, the combination of two or more “classic” features of a UTI – without vaginal irritation or discharge in females – indicates that a UTI is likely. Classic features of a lower UTI are:

- New-onset dysuria

- Increased urinary frequency

- Increased urinary urgency

- Suprapubic pain

If there are atypical features, complicating factors or diagnostic uncertainty, urine dipstick testing can be useful to indicate if an infection is likely. A positive result for leukocyte esterase or nitrites, in the presence of lower UTI symptoms, is sufficient to confirm a lower UTI diagnosis in a patient and proceed with treatment. In most cases, obtaining a midstream urine sample for microscopy, culture and sensitivity analysis is not recommended for patients with an uncomplicated UTI as the causative bacteria and antibiotic sensitivity profile are often predictable. Therefore, the initial antibiotic choice in such cases should be empiric.

For further information on diagnosing and treating lower UTIs in adults, see: “Urinary tract infections (UTIs) – an overview of lower UTI management in adults”

Clinically appropriate reasons for requesting urine microscopy, culture and sensitivity analysis in patients with a suspected UTI

Requesting urine microscopy, culture and sensitivity analysis is only indicated if there is suspicion of a UTI in certain circumstances. This may include:

- When dipstick testing is negative, but a UTI is still strongly suspected after considering differential diagnoses

- Patients with atypical symptoms, persistent symptoms despite antibiotic treatment or recurrent UTIs (three or more episodes within 12 months, or two or more within six months)

- Patients with suspected acute pyelonephritis, e.g. systemic symptoms, fever > 38°C, significant flank or suprapubic pain

- Patients with complicating factors, e.g. pregnancy, urinary catheterisation, urinary tract abnormalities, immunosuppression, renal impairment, diabetes, or other high-risk groups, e.g. males, patients aged ≥ 65 years

Summary

This audit focuses on the appropriate requesting of urine microscopy, culture and sensitivity analysis for adult patients with a suspected UTI.

Recommended audit standards

Ideally, all adult patients with a suspected UTI who have had urine microscopy, culture and sensitivity analysis requested should have an appropriate clinical reason in their record (e.g. male, diabetes) or documented in their notes (e.g. atypical symptoms). This may not be achieved on the first cycle of the audit but should be the aim for the second cycle.

Alternatively, consider a “working audit” where the data sheet is completed over time when any adult patient presents with a suspected UTI. Document whether or not urine microscopy, culture and sensitivity analysis has been requested and why that decision was made. Clinical justifications can then be compared in the second cycle.

Alternatively, consider a “working audit” where the data sheet is completed over time when any adult patient presents with a suspected UTI. Document whether or not urine microscopy, culture and sensitivity analysis has been requested and why that decision was made. Clinical justifications can then be compared in the second cycle.

Eligible patients

Any adult patient with a suspected UTI who has had urine microscopy, culture and sensitivity analysis requested in the past 12 months is eligible for this audit. N.B. Exclude urinalysis testing for other reasons.

Any adult patient who presents with a suspected UTI is eligible for the working audit.

Identifying patients

You will need to have a system in place that allows you to identify eligible patients and audit their clinical notes. Many practices will be able to do this by running a “query” through their PMS to find patients who have had a midstream urine (MSU) sample sent for urine microscopy, culture and sensitivity analysis in the past 12 months. The clinical notes of identified patients will then need to be reviewed, and those who have had the analysis requested for a suspected UTI should be selected for the audit.

If conducting a working audit, fill in the data sheet when you have a consultation with any patient who presents with a suspected UTI, until the required number of patients has been reached.

Sample size

It is likely that this audit will return a large number of eligible patients. If this is the case, select a random sample of 30 patients. A smaller sample size may be necessary if conducting a working audit to complete it within your planned time frame.

Criteria for a positive outcome

For a positive result, the patient’s clinical notes should contain a record of an appropriate clinical reason for requesting urine microscopy, culture and sensitivity analysis. This may include:

- When dipstick testing is negative but strong suspicion for a UTI remains after considering differential diagnoses

- The presence of atypical symptoms, persistent symptoms despite antibiotic treatment or recurrent UTIs (at least three episodes within 12 months, or two within six months)

- Suspected acute pyelonephritis, e.g. systemic symptoms, fever > 38°C, significant flank or suprapubic pain

- Complicating factors, e.g. pregnancy, urinary catheterisation, urinary tract abnormalities, immunosuppression, renal impairment, diabetes, or is in a high-risk group, e.g. males, aged ≥ 65 years

In the working audit, a positive result is a justified reason for whether or not urine microscopy, culture and sensitivity analysis was requested, i.e. testing was requested based on one of the reasons above, or testing was not requested as the patient did not meet any of the criteria above.

Data analysis

Use the sheet provided to record your data. The percentage achievement can be calculated by dividing the number of patients with a positive result by the total number of patients.

Optional: record justification for why urine microscopy, culture and sensitivity analysis was requested.

In the working audit (Data sheet B), record whether or not urine microscopy, culture and sensitivity analysis has been requested and why that decision was made.

Clinical audits can be an important tool to identify where gaps exist between expected and actual performance. Once completed, they can provide ideas on how to change practice and improve patient outcomes. General practitioners are encouraged to discuss the suitability and relevance of their proposed audit with their practice or peer group prior to commencement to ensure the relevance of the audit. Outcomes of the audit should also be discussed with the practice or peer group; this may be recorded as a learning activity reflection if suitable.

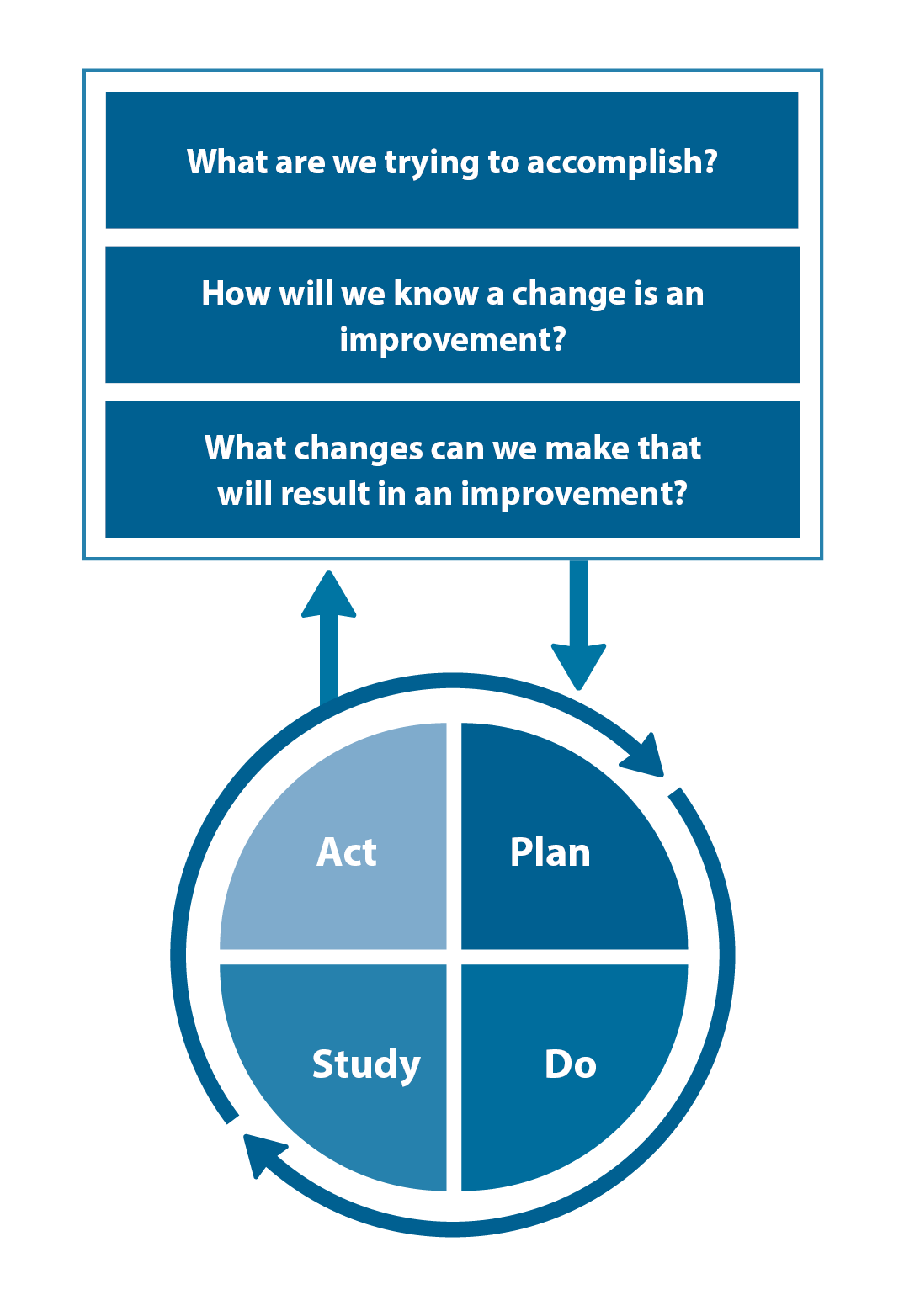

The Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) model is recommended by the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners (RNZCGP) as a framework for assessing whether a clinical audit is relevant to your practice. This model has been widely used in healthcare settings since 2000. It consists of two parts, the framework and the PDSA cycle itself, as shown in Figure 1.

1. The framework

This consists of three questions that help define the “what” and “how” of an improvement project (in this case an audit).

The questions are:

- "What are we trying to accomplish?" – the aim

- "How will we know that a change is an improvement?" – what measures of success will be used?

- "What changes can we make that will result in improvement?" – the concept to be tested

2. The PDSA cycle

This is often referred to as the “engine” for creating, testing and carrying out the proposed changes. More than one cycle is usually required; each one is intended to be short, rapid and frequent, with the results used to inform and refine the next. This allows an ongoing process of continuous learning and improvement.

Each PDSA cycle includes four stages:

- Plan – decide what the change to be tested is and how this will be done

- Do – carry out the plan and collect the data

- Study – analyse the data, assess the impact of the change and reflect on what was learned

- Act – plan the next cycle or implement the changes from your plan

Figure 1. The PDSA model for improvement.

Source: Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycles and the model for improvement

Claiming credits for Te Whanake CPD programme requirements

Practice or clinical audits are useful tools for improving clinical practice and credits can be claimed towards the Patient Outcomes (Improving Patient Care and Health Outcomes) learning category of the Te Whanake CPD programme, on a two credit per learning hour basis. A minimum of 12 credits is required in the Patient Outcomes category over a triennium (three years).

Any data driven activity that assesses the outcomes and quality of general practice work can be used to gain credits in the Patient Outcomes learning category. Under the refreshed Te Whanake CPD programme, audits are not compulsory and the RNZCGP also no longer requires that clinical audits are approved prior to use. The college recommends the PDSA format for developing and checking the relevance of a clinical audit.

To claim points go to the RNZCGP website: www.rnzcgp.org.nz

If a clinical audit is completed as part of Te Whanake requirements, the RNZCGP continues to encourage that evidence of participation in the audit be attached to your recorded activity. Evidence can include:

- A summary of the data collected

- An Audit of Medical Practice (CQI) Activity summary sheet (Appendix 1 in this audit or available on the

RNZCGP website).

N.B. Audits can also be completed by other health professionals working in primary care (particularly prescribers), if relevant. Check with your accrediting authority as to documentation requirements.