Published: July, 2024 | Review date: July, 2027

This audit identifies younger male patients, who are less likely

to present to primary care, to assess whether they have been

offered a sexual health check within the past 12 months.

This audit also provides an opportunity to check the HPV

vaccination status of these patients and offer vaccination

where appropriate.

N.B. The term “male” is used to describe the biological sex of the

patient population who are the focus of this audit. However,

we acknowledge that this may not reflect the identity of

all patients, which will include transgender girls or women,

intersex and non-binary individuals.

Rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are high in New

Zealand. Chlamydia is the most commonly reported bacterial

STI.1 Small increases in the number of infectious syphilis

and gonorrhoea cases have been reported recently; both of

which disproportionately affect men who have sex with men

(MSM).1 Genital warts are more common in males, but overall

diagnoses continue to decrease following inclusion of the

human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination (Gardasil 9) in the

National Immunisation Schedule in 2008.1

The highest rates of STIs are typically reported in younger

adults and adolescents, due to an increased prevalence

of higher risk sexual behaviours, e.g. frequently changing

or concurrent sexual partners, condomless sex. As these

infections can be asymptomatic, increased testing is essential

to prevent complications developing and transmission of

infections to others by enabling prompt treatment. Annual

STI testing is recommended for all sexually active people aged

< 30 years; more frequent testing may be indicated for certain

groups, e.g. people who have multiple sexual partners, MSM.

STI testing rates are typically lower for males than females.

Younger males in particular may rarely attend primary

care, therefore, any consultation should be considered as a

potential opportunity to initiate a discussion about sexual

health and offer STI testing as appropriate. This is also an

opportunity to check HPV vaccination status and discuss

vaccination with those who are eligible* but have not been

immunised, e.g. those who missed out on the school-based

programme.

*HPV vaccination is recommended and funded for all people aged 9

– 26 years. The vaccine can be administered (not funded) to people

aged 27 years and over if they have not been vaccinated before and

are likely to benefit, e.g. MSM, those with HIV infection or people who

are newly sexually active.

References:

- The Institute of Environmental Science and Research Ltd (ESR).

Sexually transmitted infections in New Zealand: supplementary

annual surveillance report 2022. 2023. Available from: https://www.esr.cri.nz/digital-library/sexually-transmitted-infections-annual-surveillance-report-2022/ (Accessed Jul, 2024).

For further information on how to perform a sexual

health check, see: bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2013/April/how-to-guide-sexual-health.aspx

For latest recommendations on testing, see: sti.guidelines.org.nz/sexual-health-check/

For guidance on antibiotic management of chlamydia,

gonorrhoea, Mycoplasma genitalium and syphilis infections

in primary care, see: bpac.org.nz/antibiotics/guide.aspx

For further information on HPV vaccination, including

the vaccination schedule and groups eligible for funded

vaccination, see: bpac.org.nz/2019/hpv.aspx

Summary

This audit identifies male patients aged 16 – 30 years who

have presented to primary care in the past 12 months to

assess whether they have been offered a sexual health

check or had appropriate STI testing. They should also have

a record of a completed HPV vaccination course or an offer of

immunisation to those who are eligible but have not yet been

vaccinated or completed the course.

Recommended audit standards

Ideally, all male patients aged 16 – 30 years should have

documented evidence in their patient record of having

been offered a sexual health check or had appropriate STI

testing in the previous 12 months. Any patients who do

not have the recommended information in their clinical

notes should be flagged for review. They should also have

a record of a completed HPV vaccination course or an offer

of vaccination (at any time). Any patients who do not have

the recommended information in their clinical notes and are

eligible for vaccination (i.e. aged 26 years and under) should

be flagged for review, e.g. a discussion about vaccination

at their next appointment. Also consider offering HPV

vaccination to patients aged 27 years and over if they have

not been vaccinated before and are likely to benefit (however,

this would not be funded).

Alternatively, consider a “working audit” where the data sheet is filled in over time opportunistically during consultations for

any reason with an eligible patient until the required number

of patients has been reached. If conducting a “working audit”

and there is no record of a recent sexual health check or a

discussion regarding HPV vaccination in the patient’s clinical

notes, this should be undertaken at the time, or a future

appointment booked.

Alternatively, consider a “working audit” where the data sheet is filled in over time opportunistically during consultations for

any reason with an eligible patient until the required number

of patients has been reached. If conducting a “working audit”

and there is no record of a recent sexual health check or a

discussion regarding HPV vaccination in the patient’s clinical

notes, this should be undertaken at the time, or a future

appointment booked.

Eligible patients

All male patients within the practice who are aged 16 – 30

years and have attended primary care for any reason in the

past 12 months are eligible for this audit.

Identifying patients

For the conventional audit, you will need to have a system in

place that allows you to identify eligible patients and audit

their clinical notes. Many practices will be able to do this by

running a ‘query’ through their PMS to find all male patients

aged 16 – 30 years. The notes of identified patients will need

to be reviewed and those who have attended a primary care

consultation within the past 12 months selected for the audit.

If conducting a “working audit” fill in the data sheet when you

have a consultation for any reason with an eligible patient

until the required number of patients has been reached.

If conducting a “working audit” fill in the data sheet when you

have a consultation for any reason with an eligible patient

until the required number of patients has been reached.

N.B. To increase vaccination uptake in this key population, consider

running a separate PMS ‘query’ to identify all male patients aged 16 – 30

years enrolled in the practice who have not yet received HPV vaccination

(or completed the course) and flag for discussion at the next appointment.

Sample size

The number of eligible patients will vary according to your

practice demographic. A sample size of 30 patients is sufficient

for this audit; a smaller sample size may be necessary if

conducting a working audit.

N.B. The timeframe of the audit can be extended beyond 12 months if an

insufficient number of patients are initially identified.

Criteria for a positive outcome

For a positive result for the audit, the patient’s clinical notes

should contain the following:

- Record of a discussion offering a sexual health check or

a record of recommended STI testing for their clinical

circumstances in the past 12 months; AND

- Record of completed HPV vaccination course or an offer

of vaccination at any time

Data analysis

Use the sheet provided to record your data.

In the conventional audit (Data sheet A), a positive result is

any patient who has documented evidence in their notes of

an offer of a sexual health check or a record of appropriate STI

testing in the past 12 months and a record of HPV vaccination

or a discussion offering vaccination to those in whom it is

recommended, at any time. The percentage achievement

can be calculated by dividing the number of patients with a

positive result by the total number of patients audited.

In the working audit (Data sheet B), aim to carry out a sexual

health check for as many eligible patients as possible. HPV

vaccination should also be offered to all patients in whom

vaccination is recommended but they have not yet received

it or completed the course.

In the working audit (Data sheet B), aim to carry out a sexual

health check for as many eligible patients as possible. HPV

vaccination should also be offered to all patients in whom

vaccination is recommended but they have not yet received

it or completed the course.

Clinical audits can be an important tool to identify where gaps exist between expected and actual performance. Once completed, they can provide ideas on how to change practice and improve patient outcomes. General practitioners are encouraged to discuss the suitability and relevance of their proposed audit with their practice or peer group prior to commencement to ensure the relevance of the audit. Outcomes of the audit should also be discussed with the practice or peer group; this may be recorded as a learning activity reflection if suitable.

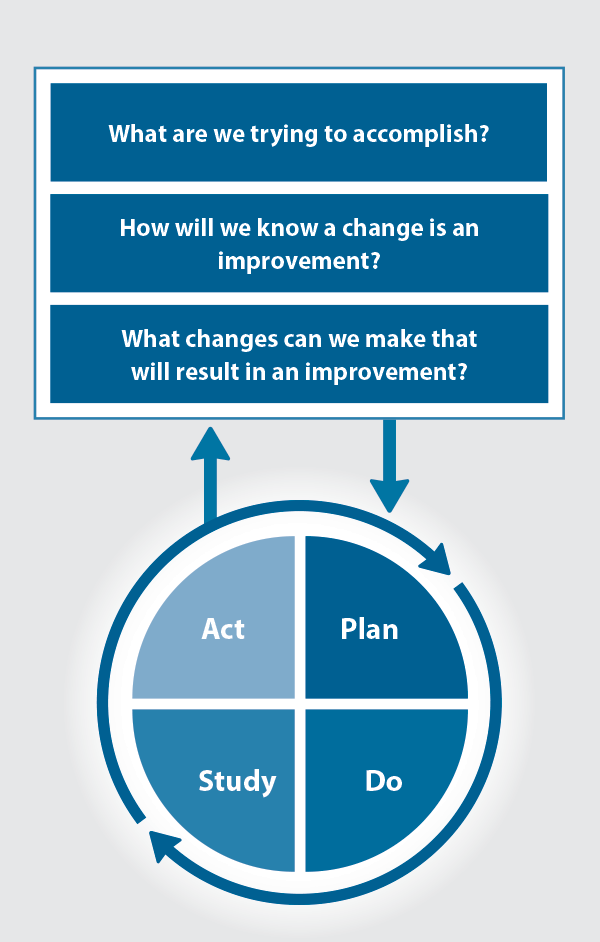

The Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) model is recommended by the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners (RNZCGP) as a framework for assessing whether a clinical audit is relevant to your practice. This model has been widely used in healthcare settings since 2000. It consists of two parts, the framework and the PDSA cycle itself, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The PDSA model for improvement.

Source: Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycles and the model for improvement

1. The framework

This consists of three questions that help define the “what” and “how” of an improvement project (in this case an audit).

The questions are:

- "What are we trying to accomplish?" – the aim

- "How will we know that a change is an improvement?" – what measures of success will be used?

- "What changes can we make that will result in improvement?" – the concept to be tested

2. The PDSA cycle

This is often referred to as the “engine” for creating, testing and carrying out the proposed changes. More than one cycle is usually required; each one is intended to be short, rapid and frequent, with the results used to inform and refine the next. This allows an ongoing process of continuous learning and improvement.

Each PDSA cycle includes four stages:

- Plan – decide what the change to be tested is and how this will be done

- Do – carry out the plan and collect the data

- Study – analyse the data, assess the impact of the change and reflect on what was learned

- Act – plan the next cycle or implement the changes from your plan

Claiming credits for Te Whanake CPD programme requirements

Practice or clinical audits are useful tools for improving clinical practice and credits can be claimed towards the Patient Outcomes (Improving Patient Care and Health Outcomes) learning category of the Te Whanake CPD programme, on a two credit per learning hour basis. A minimum of 12 credits is required in the Patient Outcomes category over a triennium (three years).

Any data driven activity that assesses the outcomes and quality of general practice work can be used to gain credits in the Patient Outcomes learning category. Under the refreshed Te Whanake CPD programme, audits are not compulsory and the RNZCGP also no longer requires that clinical audits are approved prior to use. The college recommends the PDSA format for developing and checking the relevance of a clinical audit.

To claim points go to the RNZCGP website: www.rnzcgp.org.nz

If a clinical audit is completed as part of Te Whanake requirements, the RNZCGP continues to encourage that evidence of participation in the audit be attached to your recorded activity. Evidence can include:

- A summary of the data collected

- An Audit of Medical Practice (CQI) Activity summary sheet (Appendix 1 in this audit or available on the

RNZCGP website).

N.B. Audits can also be completed by other health professionals working in primary care (particularly prescribers), if relevant. Check with your accrediting authority as to documentation requirements.