This audit identifies patients who are prescribed a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), e.g. omeprazole, and documents their management to determine whether the indication for ongoing treatment remains and if they are taking the lowest effective dose.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are indicated for the prevention and treatment of symptoms related to gastric acid secretion. There are currently three fully subsidised PPIs available in New Zealand: omeprazole, pantoprazole and lansoprazole. PPIs are highly effective and well tolerated, contributing to their widespread use; in 2022, omeprazole was dispensed to more than 600,000 people in New Zealand.1 However, PPI treatment is associated with a small increase in the risk of adverse outcomes including acute interstitial nephritis, bone fractures, gastrointestinal and respiratory infections and nutrient deficiencies, e.g. hypomagnesaemia. PPIs may also interact with other medicines by altering their absorption or hepatic metabolism and clearance. To prevent unnecessary exposure to these risks, PPIs should only be prescribed to people with a specific clinical indication for treatment, and at the lowest effective dose for the shortest period of time.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is one of the most common indications for the use of PPIs with a global prevalence of approximately 14%, however, the prevalence in New Zealand is likely higher.2, 3 Patients with uncomplicated GORD can generally be managed in a primary care setting by treating with a PPI for four to eight weeks, e.g. omeprazole 20 mg, once daily. PPIs are also frequently prescribed prophylactically to prevent gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events, e.g. ulceration and bleeding, associated with the long-term use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or dabigatran.

Because PPI use is very prevalent, each practice is likely to have a number of patients who are being treated with a higher dose than is necessary or for longer than is recommended. These patients may benefit from reducing their PPI dose, taking “as needed” or stopping the medicine completely. Abrupt withdrawal of a PPI can cause rebound gastric acid secretion, leading to symptoms which may be confused for the re-emergence of GORD and consequently the re-initiation of the PPI. Discuss the risk of rebound acid secretion with patients before reducing or stopping the PPI. These symptoms can be managed by stepping down the dose over two to four weeks, e.g. halving the daily dose, then taking the medicine on alternate days before discontinuing the PPI completely. Some patients may require another medicine to manage their rebound symptoms, e.g. a histamine H2-receptor antagonist (famotidine), antacid or an antacid combined with an alginate.

Patients who are trialling stepping down to a lower dose or stopping PPI treatment should be reminded about lifestyle strategies to help manage the symptoms of GORD. For example, weight loss, smoking cessation, eating smaller meals, avoiding alcohol, coffee and spicy or acidic foods may help to reduce symptoms such as heartburn, indigestion and regurgitation. Recommend that patients avoid eating three to four hours before lying down and to slightly elevate the head of the bed if necessary.

There will be some patients taking PPIs long-term for whom withdrawal of the PPI is inappropriate, e.g. those with Barrett’s oesophagus or taking NSAIDs or dabigatran long-term. In others, e.g. with a history of severe erosive oesophagitis, withdrawal of PPIs should only be considered after discussion with an appropriate specialist. Clinicians should ensure that a PPI prescribed prophylactically is discontinued once NSAID treatment is stopped.

For further information on GORD, see: www.bpac.org.nz/bpj/2014/june/gord.aspx

For further information on stopping PPIs, see:

www.bpac.org.nz/2019/ppi.aspx

References

- Te Whatu Ora - Health New Zealand. Pharmaceutical Data web tool. 2023. Available from: https://tewhatuora.shinyapps.io/pharmaceutical-data-web-tool/ (Accessed Feb, 2024).

- Shanika LGT, Reynolds A, Pattison S, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use: systematic review of global trends and practices. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2023;79:1159–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-023-03534-z.

- Nirwan JS, Hasan SS, Babar Z-U-D, et al. Global prevalence and risk factors of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD): systematic review with meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2020;10:5814. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62795-1.

Summary

This audit identifies patients who are currently taking a PPI to assess whether their indication for treatment remains and if they are taking the lowest effective dose. If “stepping down” is appropriate and has not yet been trialled, this can be flagged in the patient’s clinical record for discussion at their next appointment.

N.B. This audit evaluates all PPI prescribing, but could be applied to an individual PPI, e.g. omeprazole.

Recommended audit standards

Ideally, all patients who have been taking a PPI for longer than three months* should have documented evidence in their patient record of an indication for ongoing treatment or evidence of a discussion about stepping down to a lower dose or stopping completely. Any patients that do not have the recommended information in their clinical notes should be flagged for review.

* Four to eight weeks is the recommended duration of PPI treatment for GORD, however, three months has been selected pragmatically for this audit to allow sufficient time for patients that are continuing PPI treatment for longer than eight weeks to have had a review.

Eligible patients

All patients who have been taking a PPI for longer than three months are eligible for this audit.

Identifying patients

You will need to have a system in place that allows you to identify eligible patients. Many practices will be able to identify patients by running a ‘query’ through their PMS. Identify all patients who have received a prescription for a PPI, i.e. omeprazole, pantoprazole or lansoprazole, in the last 12 months and then select those who have been taking it for longer than three months.

Sample size

The number of eligible patients will vary according to your practice demographic. A sample size of 30 patients is sufficient for this audit.

Criteria for a positive outcome

For a positive result for the audit, the patient’s clinical notes should contain one of the following:

- A record of a current indication for ongoing PPI treatment, e.g. symptoms of GORD have not resolved, erosive oesophagitis, Barrett’s oesophagus, continued use of an NSAID

- A record of a discussion with the patient about “stepping down” to a lower dose or stopping the PPI completely and evidence that this process is in place, e.g. a plan for the patient to reduce their dose over a two-week period and then to stop or use as needed for symptom control

Data analysis

Use the data sheet provided to record your data. The percentage achievement can be calculated by dividing the number of patients with a positive result by the total number of patients audited.

Clinical audits can be an important tool to identify where gaps exist between expected and actual performance. Once completed, they can provide ideas on how to change practice and improve patient outcomes. General practitioners are encouraged to discuss the suitability and relevance of their proposed audit with their practice or peer group prior to commencement to ensure the relevance of the audit. Outcomes of the audit should also be discussed with the practice or peer group; this may be recorded as a learning activity reflection if suitable.

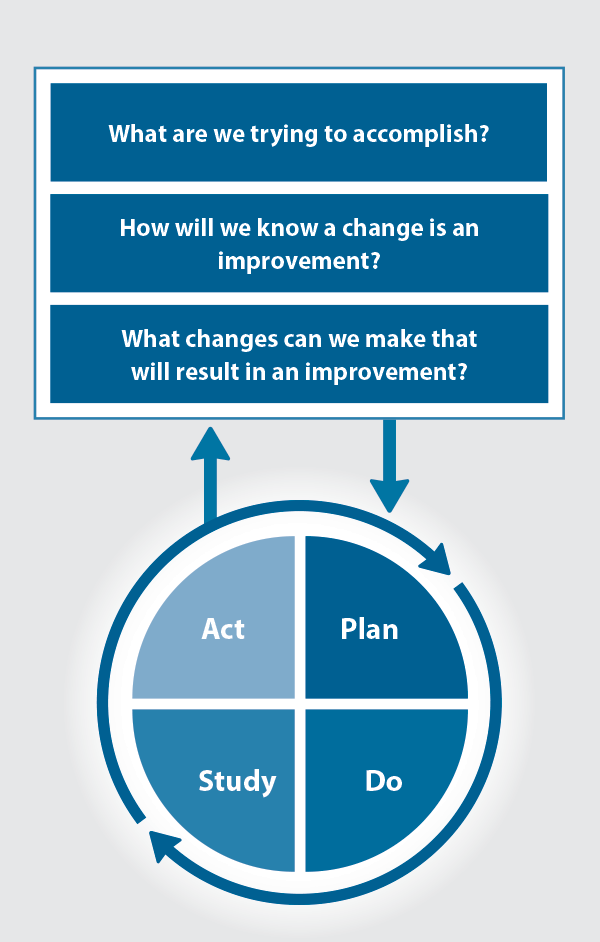

The Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) model is recommended by the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners (RNZCGP) as a framework for assessing whether a clinical audit is relevant to your practice. This model has been widely used in healthcare settings since 2000. It consists of two parts, the framework and the PDSA cycle itself, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The PDSA model for improvement.

Source: Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycles and the model for improvement

1. The framework

This consists of three questions that help define the “what” and “how” of an improvement project (in this case an audit).

The questions are:

- "What are we trying to accomplish?" – the aim

- "How will we know that a change is an improvement?" – what measures of success will be used?

- "What changes can we make that will result in improvement?" – the concept to be tested

2. The PDSA cycle

This is often referred to as the “engine” for creating, testing and carrying out the proposed changes. More than one cycle is usually required; each one is intended to be short, rapid and frequent, with the results used to inform and refine the next. This allows an ongoing process of continuous learning and improvement.

Each PDSA cycle includes four stages:

- Plan – decide what the change to be tested is and how this will be done

- Do – carry out the plan and collect the data

- Study – analyse the data, assess the impact of the change and reflect on what was learned

- Act – plan the next cycle or implement the changes from your plan

Claiming credits for Te Whanake CPD programme requirements

Practice or clinical audits are useful tools for improving clinical practice and credits can be claimed towards the Patient Outcomes (Improving Patient Care and Health Outcomes) learning category of the Te Whanake CPD programme, on a two credit per learning hour basis. A minimum of 12 credits is required in the Patient Outcomes category over a triennium (three years).

Any data driven activity that assesses the outcomes and quality of general practice work can be used to gain credits in the Patient Outcomes learning category. Under the refreshed Te Whanake CPD programme, audits are not compulsory and the RNZCGP also no longer requires that clinical audits are approved prior to use. The college recommends the PDSA format for developing and checking the relevance of a clinical audit.

To claim points go to the RNZCGP website: www.rnzcgp.org.nz

If a clinical audit is completed as part of Te Whanake requirements, the RNZCGP continues to encourage that evidence of participation in the audit be attached to your recorded activity. Evidence can include:

- A summary of the data collected

- An Audit of Medical Practice (CQI) Activity summary sheet (Appendix 1 in this audit or available on the

RNZCGP website).

N.B. Audits can also be completed by other health professionals working in primary care (particularly prescribers), if relevant. Check with your accrediting authority as to documentation requirements.