This audit identifies patients who are taking aspirin for the primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) to determine if ongoing treatment is indicated based upon guidance in the 2018 Cardiovascular Disease Risk Assessment and Management for Primary Care consensus statement.

Aspirin, along with lipid-lowering and blood pressure-lowering medicines, is indicated for the management of cardiovascular disease risk for some people. The Cardiovascular Disease Risk Assessment and Management for Primary Care consensus statement (2018), released by the Ministry of Health remains the most up to date guidance in New Zealand.1 It recommends that the estimated five-year CVD risk should be used, along with the patient’s age, to determine when aspirin should be considered for the primary or secondary prevention of CVD.

The identification of people with a low (< 5%), intermediate (5 – 15%) or high (≥ 15%) five-year CVD risk in the 2018 CVD consensus statement is based on the New Zealand Primary Prevention equations, which were developed from the New Zealand PREDICT study. Most practice management systems will have an integrated CVD risk assessment tool. Alternatively, a Canadian-based online CVD risk calculator, with the option of using PREDICT data, can be used. It is available at: https://decisionaid.ca/cvd/.

The CVD consensus statement recommends considering aspirin for primary prevention in people who have a high five-year CVD risk (≥ 15%) and are aged under 70 years. In addition, documented coronary disease, carotid disease (plaque on ultrasound) or a high coronary calcium score on CT scan (> 400) is considered equivalent to high risk (≥ 15%) and the CVD consensus statement recommends considering aspirin in people with these conditions.

For people aged 70 years and older, aspirin for primary prevention is not recommended due to the unclear balance between the benefits and harms of treatment. This recommendation is supported by evidence from the ASPREE study published in 2018 which showed that aspirin treatment increased the risk of bleeding, without reducing the number of cardiovascular events, in people in this age group.2 Aspirin is also not recommended for the primary prevention of CVD in people with a five-year CVD risk < 15% or in those with high bleeding risk.

Aspirin is recommended for all people with established CVD (see: “Definition of established CVD”)

for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events, regardless of age, as the benefits of treatment are considered

to outweigh the increased risk of bleeding.

International guidelines continue to support the use of aspirin for the primary prevention of CVD in people aged < 70 years with high CVD risk who are not at increased risk of bleeding, and for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in people with established CVD, regardless of age.3, 4

If aspirin is indicated, the benefits and risks associated with treatment should be discussed with the patient. The decision whether to initiate treatment should include consideration of factors such as the risk of bleeding, co-morbidities, history of CVD and life-expectancy. For people with a high five-year CVD risk, lipid-lowering or blood pressure-lowering medicines are strongly recommended in the 2018 CVD consensus statement. Lifestyle advice, e.g. diet, weight management, physical activity, smoking cessation, is recommended for all people, regardless of CVD risk.

Definition of established CVD

People with established CVD includes those who have a history of:

- Angina

- Coronary artery bypass grafting

- Myocardial infarction

- Percutaneous coronary intervention

- Peripheral vascular disease

- Stroke

- Transient ischaemic attack

- Congestive heart failure

People with risk factors equivalent to established CVD, i.e. a five-year risk ≥ 15%, include those with:

- Asymptomatic carotid or coronary disease, i.e. coronary artery calcium score > 400 of plaque identified on carotid

ultrasound or CT angiography

- Familial hypercholesterolaemia

- Chronic kidney disease with an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73m2

- Diabetes with an eGFR < 45 mL/min/1.73m2

For further information on the 2018 CVD risk assessment and management statement, see:

www.bpac.org.nz/2018/cvd.aspx

For further information on aspirin in the management of CVD, see:

www.bpac.org.nz/2018/aspirin.aspx

A full copy of the CVD consensus statement is available from:

www.health.govt.nz/publication/cardiovascular-disease-risk-assessment-and-management-primary-care

References

- Ministry of Health. Cardiovascular disease risk assessment and management for primary care. 2018. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/cardiovascular-disease-risk-assessment-and-management-primary-care (Accessed Feb, 2024)

- McNeil JJ, Wolfe R, Woods RL, et al. Effect of aspirin on cardiovascular events and bleeding in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1509–18. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1805819

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019;140. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

- Virani SS, Newby LK, Arnold SV, et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the management of patients with chronic coronary disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2023;148. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001168

Summary

This audit identifies patients who are taking aspirin for the primary or secondary prevention of CVD to determine if

ongoing treatment is indicated based upon the following recommendations in the 2018 CVD consensus statement:

- Aspirin is recommended for all patients with established CVD for secondary prevention

- Aspirin may be considered for primary prevention in patients aged < 70 years with an estimated five-year CVD risk

of ≥ 15%*

- Aspirin is not recommended for primary prevention in patients aged ≥ 70 years, regardless of CVD risk

- Aspirin is not recommended for primary prevention in patients with an estimated five-year CVD risk < 15%

* Estimate based upon the PREDICT equations or presence of an equivalent high-risk co-morbidity

Recommended audit standards

Ideally, all patients who are taking aspirin long-term for the management of CVD risk should have a documented indication for primary or secondary prevention in their clinical record, based upon the recommendations in the 2018 CVD consensus statement.

Eligible patients

All patients who are currently taking aspirin for the primary or secondary prevention of CVD can be audited to assess whether they have an appropriate indication for ongoing use.

Identifying patients

You will need to have a system in place that allows you to identify eligible patients and audit their clinical notes. Many practices will be able to do this by running a “query” through their PMS to find all patients taking aspirin. The notes of identified patients will need to be reviewed and those who are prescribed low-dose aspirin, i.e. 75 to 150 mg, selected for the audit.

Sample size

The number of eligible patients will vary according to your practice demographic. If a large number of results are returned, a sample size of 30 patients is sufficient for this audit. However, it is recommended that all patients taking aspirin for the prevention of CVD are subsequently reviewed.

Criteria for a positive outcome

A positive result is if a patient who has been taking aspirin for the primary or secondary prevention of CVD has documented

evidence in their patient record of:

- A five-year CVD risk score ≥ 15%* AND they are aged < 70 years, i.e. for primary prevention

- OR

- A history of established CVD, i.e. for secondary prevention

* Or high-risk equivalent co-morbidity

Data analysis

For each patient who is currently taking aspirin, record on the data sheet whether there is an indication for primary or secondary prevention of CVD. Calculate the percentage of your patients who have a current indication for aspirin treatment in the last 12 months by taking the number who meet the requirements for primary or secondary prevention and dividing it by the number of patients audited. If there is no documented evidence for primary prevention (i.e. aged ≥ 70 years or has a five-year CVD risk < 15%* ) or secondary prevention (i.e. no history of CVD), the patient should be flagged for review.

If there is no indication for continuing aspirin after the review, discuss with the patient the option of stopping treatment.

* Or no high-risk equivalent co-morbidity

For further information on starting the conversation about stopping medicines, see:

www.bpac.org.nz/2018/stopping.aspx

Clinical audits can be an important tool to identify where gaps exist between expected and actual performance. Once completed, they can provide ideas on how to change practice and improve patient outcomes. General practitioners are encouraged to discuss the suitability and relevance of their proposed audit with their practice or peer group prior to commencement to ensure the relevance of the audit. Outcomes of the audit should also be discussed with the practice or peer group; this may be recorded as a learning activity reflection if suitable.

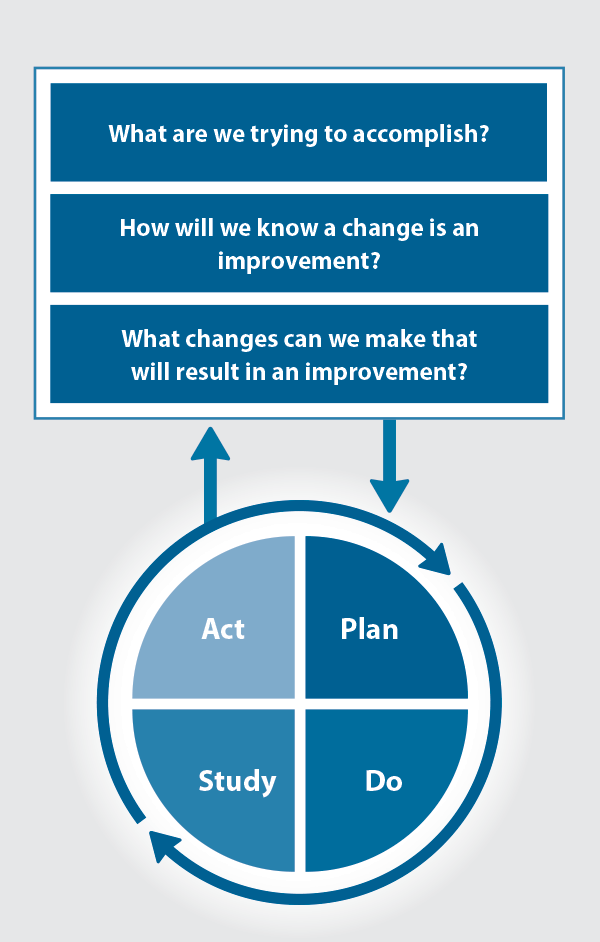

The Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) model is recommended by the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners (RNZCGP) as a framework for assessing whether a clinical audit is relevant to your practice. This model has been widely used in healthcare settings since 2000. It consists of two parts, the framework and the PDSA cycle itself, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The PDSA model for improvement.

Source: Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycles and the model for improvement

1. The framework

This consists of three questions that help define the “what” and “how” of an improvement project (in this case an audit).

The questions are:

- "What are we trying to accomplish?" – the aim

- "How will we know that a change is an improvement?" – what measures of success will be used?

- "What changes can we make that will result in improvement?" – the concept to be tested

2. The PDSA cycle

This is often referred to as the “engine” for creating, testing and carrying out the proposed changes. More than one cycle is usually required; each one is intended to be short, rapid and frequent, with the results used to inform and refine the next. This allows an ongoing process of continuous learning and improvement.

Each PDSA cycle includes four stages:

- Plan – decide what the change to be tested is and how this will be done

- Do – carry out the plan and collect the data

- Study – analyse the data, assess the impact of the change and reflect on what was learned

- Act – plan the next cycle or implement the changes from your plan

Acknowledgement

This audit was prepared in conjunction with the Heart Foundation of New Zealand.

Claiming credits for Te Whanake CPD programme requirements

Practice or clinical audits are useful tools for improving clinical practice and credits can be claimed towards the Patient Outcomes (Improving Patient Care and Health Outcomes) learning category of the Te Whanake CPD programme, on a two credit per learning hour basis. A minimum of 12 credits is required in the Patient Outcomes category over a triennium (three years).

Any data driven activity that assesses the outcomes and quality of general practice work can be used to gain credits in the Patient Outcomes learning category. Under the refreshed Te Whanake CPD programme, audits are not compulsory and the RNZCGP also no longer requires that clinical audits are approved prior to use. The college recommends the PDSA format for developing and checking the relevance of a clinical audit.

To claim points go to the RNZCGP website: www.rnzcgp.org.nz

If a clinical audit is completed as part of Te Whanake requirements, the RNZCGP continues to encourage that evidence of participation in the audit be attached to your recorded activity. Evidence can include:

- A summary of the data collected

- An Audit of Medical Practice (CQI) Activity summary sheet (Appendix 1 in this audit or available on the

RNZCGP website).

N.B. Audits can also be completed by other health professionals working in primary care (particularly prescribers), if relevant. Check with your accrediting authority as to documentation requirements.