This audit helps primary care health professionals optimise the management of stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) in their practice.

The aim is to ensure that patients with AF have their stroke risk managed appropriately according to their current risk of stroke.

Atrial fibrillation affects 5% of people in New Zealand aged over 65 years, and 11% aged over 75 years.1

People with atrial fibrillation have a four to five-fold increased risk of stroke.2

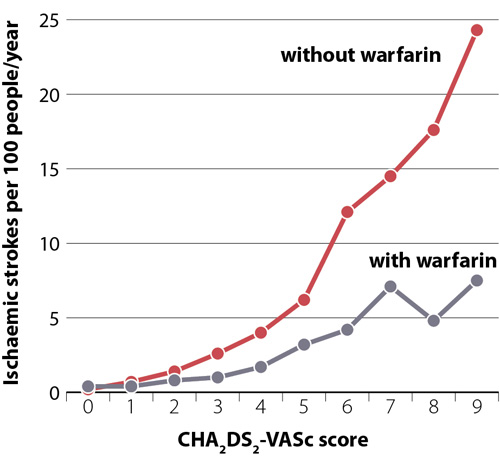

The use of anticoagulants in people with AF significantly reduces the risk of stroke (Figure 1) as well as mortality, with greater benefits expected in people at higher risk. The risk of stroke increases according to age, sex and co-morbidities. The CHA2DS2-VASc score can be used to quantify the risk of stroke in patients with AF (Table 1). In New Zealand it is estimated that 40% of patients with AF who are likely to benefit from an anticoagulant are not prescribed one.1 Many of these patients are prescribed antithrombotic medicines, such as aspirin or clopidogrel, however, these are no longer recommended for reducing stroke risk in patients with AF.3, 4

For an online CHA2DS2-VASc calculator, see: www.chadsvasc.org

Figure 1: Rates of ischaemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation with and without the use of

warfarin across CHA2DS2-VASc scores. Data from Allan et al.4

Table 1: Using the CHA2DS2-VASc score to guide anticoagulant prescribing for patients with atrial fibrillation2, 3

| Risk factor for stroke |

Points |

| Congestive heart failure |

1 |

| Hypertension or current antihypertensive medicine use |

1 |

| Aged 75 years or over |

2 |

| Diabetes mellitus |

1 |

| Stroke, transient ischaemic attack or thromboembolism |

2 |

| Vascular disease |

1 |

| Aged 65–74 years |

1 |

| Sex category |

1 if female |

| Total |

0 – 8 for males |

1– 9 for females |

| Offer anticoagulation to patients with scores |

≥ 1 for males |

≥ 2 for females |

Recommendations

Treatment options depending on stroke risk

Patients with the lowest CHA2DS2-VASc risk scores for their sex (zero for males, one for females) should not use an anticoagulant. These scores correspond with rates of ischaemic stroke less than 1 per 100 people year; such patients are unlikely to benefit from anticoagulant (or antiplatelet) use and be exposed to unnecessary risks.5

Anticoagulation should be considered for all patients with risk scores ≥ 2; males with a risk score of one may also benefit from anticoagulation.3 Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), e.g. dabigatran or rivaroxaban, are generally favoured over vitamin K analogues, e.g. warfarin.* 3 DOACs have been shown to have comparable or reduced relative risk of major bleeding events, compared to warfarin, without the need for regular international normalised ratio (INR) monitoring, and with fewer food and medicine interactions.3

*N.B. Warfarin is preferred in certain patient groups, e.g. those with a creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min, an elevated bleeding risk (high HAS-BLED score), prosthetic heart valve, moderate-to-severe mitral stenosis or who are currently pregnant (avoid in first trimester and two-to-four weeks before delivery; a low molecular weight heparin is an alternative anticoagulant option during pregnancy).3, 6, 7

For further information, see: “Re-thinking the management of atrial fibrillation” and “An update on managing patients with atrial fibrillation”

Summary

This audit identifies patients with AF in order to assess whether their use of anticoagulants is appropriate for their current stroke risk.

Recommended audit standards

Ideally, all patients who can benefit from using an anticoagulant, i.e. with a CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥ 2 for females or ≥ 1 for males, should either be prescribed a DOAC (i.e. dabigatran or rivaroxaban) or have a documented reason why not. Patients at low risk, i.e. CHA2DS2-VASc scores below these thresholds, should not be prescribed an anticoagulant.

Identifying eligible patients

You will need to have a system in place that allows you to identify patients with AF. Many practices will be able to do this by running a “query” through their PMS.

Sample size

The sample size is ideally all patients in the practice with a diagnosis of AF, but if this number is too large, a sample size of 30 patients is sufficient

for the purpose of the audit. However, it is recommended that all eligible patients are reviewed subsequently.

Review of stroke risk

Criteria for a positive result

A positive result is if a patient with AF fits into one of the following categories:

- They are prescribed a DOAC, and this remains appropriate

- They are not prescribed a DOAC and this is appropriate:

- Due to contraindications

- As they do not require one, based on a recent review of their stroke risk (see below)

- Due to patient preference, i.e. anticoagulation was recommended based on their current stroke risk but after an informed discussion, treatment was declined

- As they are taking warfarin instead and there is clinical justification, e.g. CrCl < 30mL/min, high HAS-BLED score, prosthetic heart valve, mitral stenosis, pregnancy

It is recommended that a patient’s stroke risk should be reviewed:4

- When they reach the age of 65 years

- When they develop additional risk factors for stroke, such as diabetes, heart failure or coronary heart disease

- Annually if they are not prescribed an anticoagulant due to contraindications, bleeding risks or patient preference

Review patients not taking any anticoagulant to see if they would benefit from starting one, e.g. check if they have had a recent review of their stroke risk, and whether any

factors have changed in their clinical condition or preference for treatment. Review patients taking warfarin without clinical justification to see if they would benefit

from being switched to a DOAC.

The first step to improving medical practice is to identify the criteria where gaps exist between expected and actual performance and then to decide how to change practice.

Once a set of priorities for change have been decided on, an action plan should be developed to implement any changes.

Taking action

It may be useful to consider the following points when developing a plan for action (RNZCGP 2002).

Problem solving process

- What is the problem or underlying problem(s)?

- Change it to an aim

- What are the solutions or options?

- What are the barriers?

- How can you overcome them?

Overcoming barriers to promote change

- Identifying barriers can provide a basis for change

- What is achievable – find out what the external pressures on the practice are and discuss ways of wdealing with them

in the practice setting

- Identify the barriers

- Develop a priority list

- Choose one or two achievable goals

Effective interventions

- No single strategy or intervention is more effective than another, and sometimes a variety of methods are needed to

bring about lasting change

- Interventions should be directed at existing barriers or problems, knowledge, skills and attitudes, as well as performance

and behaviour

Monitoring change and progress

It is important to review the action plan developed previously at regular intervals. It may be helpful to review

the following questions:

- Is the process working?

- Are the goals for improvement being achieved?

- Are the goals still appropriate?

- Do you need to develop new tools to achieve the goals you have set?

Following the completion of the first cycle, it is recommended that practitioners complete the first part of the

CQI

activity summary sheet (Appendix 1).

Undertaking a second cycle

In addition to regular reviews of progress with the practice team, a second audit cycle should be completed in order to quantify progress on

closing the gaps in performance.

It is recommended that the second cycle be completed within 12 months of completing the first cycle. The second cycle

should begin at the data collection stage.

Following the completion of the second cycle it is recommended that practices complete the remainder of the

Audit of Medical Practice summary sheet.

Claiming credits for Te Whanake CPD programme requirements

Practice or clinical audits are useful tools for improving clinical practice and credits can be claimed towards the Patient Outcomes (Improving Patient Care and Health Outcomes) learning category of the Te Whanake CPD programme, on a two credit per learning hour basis. A minimum of 12 credits is required in the Patient Outcomes category over a triennium (three years).

Any data driven activity that assesses the outcomes and quality of general practice work can be used to gain credits in the Patient Outcomes learning category. Under the refreshed Te Whanake CPD programme, audits are not compulsory and the RNZCGP also no longer requires that clinical audits are approved prior to use. The college recommends the PDSA format for developing and checking the relevance of a clinical audit.

To claim points go to the RNZCGP website: www.rnzcgp.org.nz

If a clinical audit is completed as part of Te Whanake requirements, the RNZCGP continues to encourage that evidence of participation in the audit be attached to your recorded activity. Evidence can include:

- A summary of the data collected

- An Audit of Medical Practice (CQI) Activity summary sheet (Appendix 1 in this audit or available on the

RNZCGP website).

N.B. Audits can also be completed by other health professionals working in primary care (particularly prescribers), if relevant. Check with your accrediting authority as to documentation requirements.