Lactose is a disaccharide naturally found in dairy products including milk, yoghurt, cream, chocolate, ice cream and cheese.1 It

can also be used as a flavour enhancer in processed foods such as potato chips, crackers, margarine and bread.2

Lactose malabsorption. Approximately 70% of the world’s population aged ten years or older is affected

by lactose malabsorption, i.e. the failure to absorb lactose in the small intestine due to lactase deficiency or other intestinal

pathology, with most causes being genetically determined (see: “There are four types of lactase deficiency”).2,

3 People from Middle Eastern countries (70%), Asia (64%) and Africa (63 – 65%) have higher rates of lactose malabsorption,

while lower rates are reported in Eastern Europe, Russia and former Soviet Republics (47%), Northern America (42%) and Northern,

Western and Southern European countries (28%).3 Within Asia, the prevalence of lactose malabsorption is estimated

to range considerably; from 58% in Pakistan to 100% in South Korea.3 Both males and females are affected equally

worldwide.4

Lactose intolerance. When lactose malabsorption, i.e. the inability to digest lactose, causes gastrointestinal

symptoms it is referred to as lactose intolerance (see: “Gastrointestinal symptoms characterise lactose

intolerance”).2 Many people with lactose malabsorption will not develop lactose intolerance.2 The

likelihood of developing symptoms depends on the amount of lactose ingested, whether lactose is eaten with other foods that

affect transit through the intestine to the colon, the amount of lactase expression in the small intestine, composition

of the microbiome and history of gastrointestinal disorders or surgery.2

The estimated prevalence of lactose intolerance in New Zealand.

The prevalence of lactose intolerance is more difficult to estimate than lactose malabsorption as studies mainly rely

on self-reported symptoms during a lactose challenge, which are rarely blinded; self-reported lactose intolerance has a

sensitivity of 30 – 71% and specificity of 25 – 87%.2, 5 Of the limited New Zealand data available, an increased

prevalence of lactose malabsorption in Māori and Pacific peoples has been observed compared to New Zealand Europeans, based

on breath hydrogen testing (see: “Laboratory tests have a limited role in diagnosing lactose intolerance

in New Zealand”).6, 7 A study conducted in Christchurch in 2010 found that the overall prevalence of primary

lactose intolerance determined by genetic testing was 8% (among 1,064 participants); of the 30 Māori and Pacific participants,

the prevalence was 30%.8

There are four types of lactase deficiency that can result in lactose intolerance

Primary lactase deficiency is the most common cause of lactose intolerance (sometimes referred to as

lactase non-persistence or adult or late-onset lactose intolerance).2 Lactase concentrations reach their peak

around the time of birth in most people, and decline after the usual age of weaning.2, 9 The timing and rate

of this decline is genetically determined.10 Onset of primary lactase deficiency is typically subtle and progressive

over several years, with most people diagnosed in late adolescence or adulthood.2, 9, 10 However, acute development

is also possible.10

Secondary lactase deficiency (also referred to as acquired lactase deficiency) is transitory and can

occur after a gastrointestinal illness that alters the intestinal mucosa resulting in reduced lactase expression.2,

11 Secondary lactase deficiency is common in children after rotaviral (and other infectious) diarrhoea. Giardiasis,

cryptosporidiosis and other parasitic infections of the proximal small intestine often lead to lactose malabsorption.9 Secondary

lactase deficiency may also occur with coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, small intestinal bacteria overgrowth,

cows’ milk protein allergy (CMPA)-induced enteropathy and immune-related illnesses such as HIV.9 In addition,

some medicines can cause villous atrophy resulting in secondary lactase deficiency, e.g. aminoglycosides, tetracyclines,

colchicine, chemotherapy treatments.12 Secondary lactase deficiency usually resolves after one to two months

but may be permanent if caused by a long-term condition.

Developmental lactase deficiency (neonatal) occurs in premature infants.9 This condition

is usually temporary and rapidly improves as the intestinal mucosa matures.9 Lactase and other disaccharidases

are deficient until after 34 weeks gestation.9

Congenital lactase deficiency (alactasia) is a life-long genetic condition involving the complete deficiency

of lactase expression from birth, despite the person having an otherwise normal intestinal mucosa.2 Alactasia

is extremely rare; it has been diagnosed in fewer than 50 people worldwide.2, 9

Gastrointestinal symptoms characterise lactose intolerance

In general, the symptoms of lactose intolerance are often non-specific, mild and vary between individuals.2, 11 Symptoms

usually occur between 30 minutes and a few hours after the ingestion of lactose.13 The severity of symptoms

is influenced by the degree of lactase deficiency and the amount of lactose consumed; typically the more lactose consumed,

the more frequent or severe the symptoms.13 In children, diarrhoea is often more pronounced, particularly those

with secondary lactose deficiency.9

Symptoms result from two main causes (see: “Pathophysiology of lactase deficiency”):2

- Undigested lactose acting as an osmotic laxative (diarrhoea, abdominal pain)

- Intestinal bacteria using lactose as a growth substrate, resulting in production of hydrogen, carbon

dioxide and methane gases (flatulence, dyspepsia, abdominal distension or borborygmi [stomach gurgling])

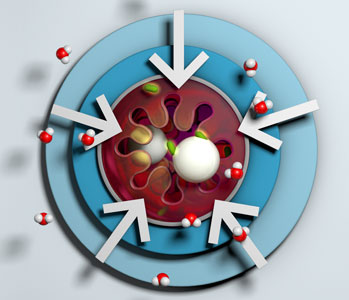

Pathophysiology of lactase deficiency

Lactase is an enzyme produced by cells located in the microvilli of the small intestine which hydrolyses dietary lactose

(a disaccharide sugar) into glucose and galactose (monosaccharide sugars) for transport across the cell membrane. In the

absence or deficiency of lactase, unabsorbed lactose causes an influx of fluid into the bowel lumen, due to osmotic pressure.

Unabsorbed lactose then enters the colon and is used as a substrate by intestinal bacteria, producing gas and short-chain

fatty acids via fermentation. The fatty acids cannot be absorbed by the colonic mucosa, therefore more fluid is drawn into

the bowel. A proportion of the lactose can be absorbed but the overall result of ingestion is a substantial rise of fluid

and gas in the bowel, causing the symptoms of lactose intolerance.2

Lactose intolerance is usually diagnosed by dietary challenge

- Step 1: Rule out other causes

- Step 2: Dietary challenge

- Step 3: Further investigation, if dietary challenge inconclusive

Lactose intolerance can be suspected in people who report gastrointestinal symptoms following the ingestion of milk or

milk products. An accurate diagnosis is important as it can significantly relieve a person’s anxiety and help them to avoid

inappropriate investigation and treatment. For people who present in primary care with severe or persistent gastrointestinal

symptoms, other potential causes should also be excluded (see: “Differential diagnoses to consider”). In particular, an

underlying secondary cause of lactose intolerance should be ruled-out in children, e.g. rotavirus infection, giardiasis

or coeliac disease. Self-diagnosis of lactose intolerance is not recommended as it could lead to unnecessary dietary restrictions

and expense, lack of essential nutrients and most importantly, failure to detect a more serious gastrointestinal problem;

other physiological and psychological factors can contribute to gastrointestinal symptoms that mimic lactose intolerance.14

A lactose-free diet should be trialled for two to four weeks when lactose intolerance is suspected.14 It

is important that all sources of lactose are eliminated, so patients should be advised to read food labels carefully to

identify “hidden” sources of lactose, which are particularly common in processed foods, e.g. whey, cheese, milk by-products,

milk solids, milk powder.14 Lactose can then be re-introduced to the diet. If symptoms improve during the two

to four week period and return when lactose is reintroduced, the diagnosis can be made.14

N.B. Some prescription and over-the-counter medicines e.g. oral contraceptive pills and nitrofurantoin (100 mg, modified

release), contain a small amount of lactose, but not enough to cause gastrointestinal symptoms in someone with lactose intolerance.11

If dietary challenge is inconclusive or self-reported symptoms are unreliable, further investigations may be required.

However, laboratory testing for lactose intolerance (see below) will often not provide a definitive diagnosis and the availability

of tests throughout New Zealand is variable.

Laboratory tests have a limited role in diagnosing lactose intolerance in New Zealand

Although laboratory testing is often cited in literature to aid in the diagnosis of lactose intolerance, most of these

tests are not widely accessible in New Zealand or not publicly funded, and some lack sensitivity and/or specificity. If

there is significant uncertainty concerning a diagnosis, consider asking your local laboratory if any additional tests are

available, such as:2, 9, 14

- Breath hydrogen test - measures

the level of hydrogen in exhaled air after ingestion of lactose, following overnight fasting. Currently considered the most

reliable laboratory method for diagnosing lactose malabsorption (sensitivity is 80 – 90%) but false negatives can occur

due to breath hydrogen production associated with other conditions unrelated to lactose digestion, e.g. gut motility disorders.

Breath hydrogen testing is usually not possible in young children due to the need for wearing a tight-fitting mask.

- Lactose tolerance test –

measures blood glucose levels after ingestion of lactose. Less reliable than the breath hydrogen test (sensitivity

is 75%). Requires significant adherence and is not suitable for children.

- Faecal pH test – non-specific

marker for lactose (or other carbohydrate) malabsorption. A pH of < 6.0 suggests lactose intolerance. Because of the

high rate of false-negative results, this test is only recommended in infants aged under two years.

- Faecal reducing substances –

another indirect test for lactose (or other carbohydrate) malabsorption. A positive test suggests an absence of the

corresponding enzyme. However, false negatives can occur if the person has not recently ingested lactose.

- Small bowel disaccharidases –

requires duodenal biopsy in secondary care. This test may occasionally be considered in the context of secondary

lactose intolerance where a gastroscopy is being performed to determine an underlying cause (e.g. coeliac disease, Crohn’s

disease, protracted diarrhoea).

- Genetic testing for hereditary lactase

persistence – tests for a cytosine (C)/thymine (T) single nucleotide polymorphism upstream of the lactase gene;

T/T or C/T genotypes are lactose tolerant, while C/C genotype is lactose intolerant15, 16

Do not routinely request skin prick or serum allergen-specific IgE tests as lactose intolerance is not immune

mediated. However, these tests may be considered to rule out CMPA if this is suspected.

N.B. There are various online allergy testing services marketed to the public. These are recommended against by the Australasian

Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA) due to the potential for harms from misdiagnosis. The full ASCIA position

statement is available here:

www.allergy.org.au/images/stories/pospapers/ASCIA_HP_Evidence-Based_Vs_Non_Evidence-Based_Allergy_Tests_Treatments_2021.pdf

Differential diagnoses to consider

If a dietary challenge proves inconclusive, alternative diagnoses should be considered, including:17

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Coeliac disease

- Diverticular disease

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Bacterial infection, e.g. Clostridium difficile

- Parasitic disease, e.g. giardiasis

- Cystic fibrosis

- Inadvertent or excessive laxative ingestion,

e.g. in products that act as natural laxatives

- Mechanical bowel compromise

- Bowel neoplasm or polyp

Lactose does not need to be completely restricted

- Step 1: Confirm diagnosis of lactose intolerance

- Step 2: Determine how much lactose can be tolerated without symptoms

- Step 3: Encourage gradual reintroduction of milk and milk products – this usually improves symptoms and tolerance

The complete avoidance of all lactose-containing foods is not recommended to manage primary lactose intolerance.1 Instead,

people should start with a more restricted diet and gradually increase the consumption of lactose-containing foods according

to their individual tolerance level.18 Consistency is the key to building tolerance; continual exposure often

enhances the number and efficiency of colonic bacteria capable of metabolising lactose, thereby producing fewer symptoms.19 The

majority of people, including children, can tolerate up to 5 g of lactose (approximately ½ cup milk) on its own, and up

to one to two cups of milk in total per day, when eaten with other foods (e.g. cereal) or spread out across the day.1,

2 Consuming lactose with meals rather than on an empty stomach slows the release of lactose in the small intestine,

and people can experiment to see which foods are more tolerable.18

Some lactose-containing foods are better tolerated than others

Better tolerated dairy products include yoghurt with live culture and hard cheese (especially aged) because the lactose

is partially hydrolysed by bacteria during preparation and gastric emptying is slower due to their thicker consistency.1,

9 Dairy products with a higher fat content or higher osmolality are also better tolerated due to delayed gastric emptying,

e.g. ice cream or chocolate milk.20 Symptoms may be more severe with skim milk (green top) than whole milk due

to the higher lactose and lower fat content.1, 20

Probiotics may be beneficial for some people

Probiotic supplementation may be beneficial for symptom relief in some people with lactose intolerance by promoting lactose

digestion.21 A 2020 systematic review of randomised controlled trials found an overall positive association between

probiotic supplementation and reduced gastrointestinal symptoms of lactose intolerance, although the effect size varied

and the quality of evidence was low.21 Probiotic strains that were shown to be beneficial included Lactobacillus

acidophilus, L. reuteri, L. rhamnosus and L. bulgaricus, Streptococcus thermophilus and Bifidobacterium

longum (dose range 108 – 1011 colony-forming units [CFU] per day).21

Lactose-free milks and milk alternatives are usually not required

Lactose-free milk or milk alternatives are generally not necessary unless large quantities of milk are consumed, or in

the rare case of intolerance to even small amounts of milk (in which case lactose-free foods may also need to be considered).

If these alternatives are required, the milk substitutes selected should be fortified with calcium and vitamin D to prevent

deficiencies.22 For children aged under five years, almond, coconut, rice and oat milk alternatives should not

be used as the main milk source as they are not nutritionally adequate.22 Fortified soy milk is recommended if

an alternative to cows’ milk is required in children. N.B. Soy milk or infant formula is generally not advised in children

aged under 12 months (see: “Feeding options for infants”).23

Maintaining calcium and vitamin D intake when minimising lactose in the diet

Adequate calcium and vitamin D intake are particularly important during childhood and adolescence for optimal peak bone

mass.24 People with lactose intolerance should continue to have at least two servings of milk or milk products

daily if tolerated in multiple small doses or with food.22 If this is not possible, calcium-fortified milk or

fortified milk substitutes should be considered as tolerated, and the diet should be supplemented through intake of non-dairy

calcium-rich food, e.g. bony fish, tofu, dark green leafy vegetables and nuts and seeds.1, 22 As sunlight is

the primary source of vitamin D, all people should be advised to take a daily walk or other form of outdoor activity.25

Lactase enzymes may be helpful alongside dietary management

Lactase enzyme supplements (available over-the-counter, not funded) should be considered as an adjunct, not a substitute

for dietary management; if dairy products can be tolerated in small amounts, enzyme supplements are unnecessary.2 Enzyme

supplements may not completely relieve symptoms and it is difficult to determine the effective dose.2

Feeding options for infants with lactose intolerance

In general, infants with lactose intolerance should continue breastfeeding.9 Breastfeeding mothers do not have

to eliminate lactose containing foods from their diets; the amount of lactose present in breastmilk is largely independent

of maternal consumption.9 Formula-fed infants may initially require a lactose-free formula, but reintroduction

of lactose containing formula or foods should be trialled after two to four weeks, as tolerated.9 In New Zealand,

lactose-free and soy milk infant formulas are available from supermarkets and pharmacies (not funded). Ongoing use of soy

formula in infants aged under 12 months is generally not recommended, but could be considered in infants aged over six months

if they are unable to tolerate adequate quantities of cows’ milk formula.23 Lactose-free infant formula can be

used in infants from birth.26

N.B. For guidance on feeding for infants with CMPA, see: bpac.org.nz/2019/cmpa.aspx

Managing secondary lactose intolerance

Short periods of lactose intolerance are common in children following infectious diarrhoea.27 In infants aged

under three months or malnourished children, this may negatively influence recovery from the primary illness.28 A

meta-analysis of clinical trials found that a lactose-free diet in non-breastfed infants may reduce the duration of diarrhoea

by up to 18 hours.27 Diluting lactose-containing milk has not been shown to resolve diarrhoea earlier compared

to undiluted milk (low quality evidence).27 Breastfed infants with temporary lactose intolerance can continue

to safely breastfeed.9

In general, treatment of the cause of the secondary lactase deficiency will lead to restoration of lactase activity.9 Therefore,

a lactose-free diet is usually only required temporarily until secondary lactase deficiency resolves.

Lactose intolerance is NOT an allergy to milk

In cows’ milk allergy, children are allergic to the protein in milk.

CMPA is one of the most common food allergies in young children (prevalence of 2 – 3% of children before age three years).29 The

prevalence in adults is much lower (approximately 0.5%).30 CMPA is reported to resolve in approximately half

of children before age 12 months, and in up to 90% by age five years.31

There are two types of clinical manifestation of CMPA:29

- IgE-mediated (Immediate): Symptoms usually develop within minutes to one hour after ingestion of cows’

milk. Symptoms include eczema, urticaria, rhinitis, cough, wheezing, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhoea. Life threatening

anaphylaxis is possible but rare.

- Non-IgE mediated (Delayed): Symptoms typically occur more than two hours or even days following ingestion

of cows’ milk. Symptoms include vomiting, diarrhoea, blood in stools, with or without eczema.

Differentiating between lactose intolerance and CMPA:

- CMPA can manifest during breastfeeding (due to cows’ milk ingested by the mother), in an infant on a cows’ milk-based

formula or shortly after weaning. Lactose intolerance is usually seen after age two years.

- Infants with lactose intolerance may safely breastfeed without the need for any maternal dietary modification, but mothers

may need to remove dairy products from their diet if their infant is diagnosed with CMPA

- Children with lactose intolerance can usually tolerate small amounts of dairy products, whereas in milk allergy, small

traces usually cause symptoms. N.B. IgE mediated CMPA reactions typically have a more rapid onset than non-IgE-mediated

reactions or symptoms of lactose intolerance.29

- Differentiation is usually possible based on clinical symptoms

For further detail on the diagnosis and management of CMPA, see “Managing cows’ milk protein allergy in infants”,

available from: bpac.org.nz/2019/cmpa.aspx

Clinician’s Notepad: lactose intolerance

If a person reports gastrointestinal symptoms that consistently occur following the ingestion of milk or milk products

- First rule out other possible causes of symptoms –

particularly if symptoms are severe or persistent, e.g. irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease

-

Secondary causes should be strongly considered in children, e.g. rotavirus infection, giardiasis or coeliac disease

-

If there is no other obvious cause, a lactose-free diet should be trialled for two to four weeks; ensure the patient is aware of

“hidden” sources of lactose which are common in processed foods

-

At the end of the trial, the patient should re-introduce lactose; if symptoms have improved during the trial and return when

lactose is reintroduced, then this is sufficient to diagnose lactose intolerance

-

Do not routinely request skin prick or serum allergen-specific IgE tests unless cows’ milk protein allergy is

suspected as lactose intolerance is not immune-mediated

-

If the dietary challenge is inconclusive or there is uncertainty, discuss with your local laboratory whether additional testing

is available, e.g. breath hydrogen testing, or consult with a secondary care clinician

Management of lactose intolerance

-

Lactose usually does not need to be excluded from the diet; people should start with a more restricted diet and gradually

increase the consumption of lactose-containing foods according to individual tolerance level

- Most people can tolerate up to 5 g of lactose (approximately ½ cup milk) on its own, and up to one to two cups of milk

in total per day, when eaten with other foods or spread out across the day

-

Some lactose-containing foods are better tolerated than others, e.g. yoghurt with live culture or dairy products with higher fat content

-

Lactose-free milks and alternative milks are usually not required but if used (or if sufficient quantities of cow’s milk cannot be consumed)

must be fortified with calcium and vitamin D to meet the recommended intake

-

Probiotics or lactase enzyme supplements (not funded) may be beneficial for some people alongside dietary management, however,

these are not routinely required and efficacy varies

-

Infants with lactose intolerance should continue breastfeeding and the mother does not need to eliminate lactose from her

diet; lactose-free infant formulas are available, if required

-

A temporary lactose-free diet may be beneficial for people with secondary lactose intolerance, e.g. following a bout of infectious

diarrhoea, to promote recovery from the primary illness