Key practice points:

- Cachexia is a complex metabolic

syndrome characterised by muscle wasting and weight loss (with or without loss of fat), accompanied by an underlying illness

- Cachexia is distinctly different

from malnutrition due to malabsorption or anorexia, which are typically associated with loss of fat mass before muscle

(however, they can occur simultaneously with cachexia – see below)

- Cachexia frequently develops

in people with cancer where it can result from cancer treatment or the malignancy itself

- In advanced cancer, cachexia

usually occurs in combination with anorexia, often termed anorexia-cachexia syndrome; interventions are aimed at

concurrent management

- There is an opportunity for

early diagnosis and management of cancer-related cachexia by primary care clinicians, which may improve patient outcomes

and quality of life

- A multi-modal approach to

cachexia management is recommended, combining nutritional, pharmacological, physical and psychosocial interventions

- Current pharmacological treatment

interventions for cachexia include corticosteroids and progestogens, e.g. megestrol; these are associated with modest

benefits on quality of life and weight

Cachexia is a complex metabolic syndrome that occurs in people with long-term, terminal conditions such as advanced cancer,

dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease and congestive heart failure.* Characteristics

of cachexia include weight loss, muscle wasting, metabolic changes and increased energy expenditure (see “Mechanisms

of cancer cachexia”).1, 2 In advanced/pre-terminal cancer, cachexia is usually accompanied by anorexia, termed

the cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome.3 Cachexia affects approximately half of all people with advanced stage

cancer and is responsible for one in five cancer-related deaths.4, 5 The incidence and severity of cachexia in

people with cancer depends on multiple factors, such as the type of cancer, stage and tumour characteristics.

Cachexia is often under-recognised.6 Early detection and management by primary care can make significant differences,

not only relating to patient prognosis and quality of life, but also by improving the efficacy of chemotherapy and reducing

treatment-associated adverse effects.7 It is essential to help the patient and their family/whānau understand

the causes and mechanisms of cachexia and that it is an expected part of the cancer process for some people.

*This article focuses on cancer cachexia; many of the management strategies, however, may also

be applicable to patients with non-cancer cachexia.

Stages of cachexia

Cancer cachexia can be divided into three clinical stages, with different treatment priorities (Table 1).

The rate at which a patient will progress through the stages is variable, and some will not progress beyond a certain stage.

Table 1: Criteria for classifying stage of cachexia.1, 9

| Stage |

Criteria |

Goal |

| Pre-cachexia |

Weight loss ≤ 5% over six-months in addition to clinical signs of anorexia, inflammation and/or metabolic changes,

e.g. impaired glucose tolerance |

Preserve muscle mass |

| Cachexia |

Weight loss > 5%, or ≥ 2% in patients already showing depletion in skeletal muscle mass or BMI ≤ 20 kg/m2 |

Reduce rate of muscle mass loss |

Refractory cachexia

(usually anorexia-cachexia syndrome) |

Variable degree of cachexia where there is no response to cancer treatment, life expectancy less than three months

and a Performance Status score of 3 – 4* |

Maintain quality of life, symptom palliation and control |

*The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status is a globally accepted consistent measure of the

impact of cancer on daily living abilities. Further information is available at

https://ecog-acrin.org/resources/ecog-performance-status

Assessment and diagnosis

There is no single screening tool that is effective at detecting cachexia in every case. A cancer care review, e.g. at

six months post-diagnosis, can provide an opportunity for clinicians to ask about any treatment-related problems or psychosocial

effects that may be predictive of cachexia.

In general, international guidelines recommend assessing:10–13

- Weight and musculature – measure weight, body mass index (BMI) and check for any changes in body composition;

cachexia often presents as disproportionate and excessive loss of lean body mass (i.e. muscle). Assess for signs of reduced

strength (handgrip test).

- Appetite and food intake – ask about eating habits, including quantities and types of food eaten, and

if this has changed over time, consider potential causes of anorexia that can be addressed, e.g. oral issues, nausea and

vomiting, constipation, medicine interactions or adverse effects. Consider malabsorption, particularly if the primary cancer

diagnosis affects the pancreas, upper gastrointestinal tract or stomach. Symptoms may include abdominal cramps following

meals, flatulence, bloating and diarrhoea/steatorrhoea.

- Other clinical features – ask about quality of life, physical activity, fatigue and mood; screening

for depression may be useful

- Investigations – consider testing for inflammation and alterations in nutrient metabolism which often

present as hyperglycaemia or hypertriglyceridaemia. Blood tests may include CRP, lipids, HbA1c, FBC and LFTs.

Diagnostic criteria for cachexia

New Zealand palliative care guidelines state that cachexia should be considered in a patient with ≥ 5% loss of body weight

or BMI ≤ 20 kg/m2 and three or more of the following:1

- Decreased muscle strength

- Fatigue or reduced physical activity

- Anorexia

- Low muscle mass*

- Abnormal biochemistry:

- CRP > 5 mg/L

- Hb < 120 g/L (consider male/female differences in Hb levels)

- Serum albumin < 32 g/L

If a patient is losing weight but the albumin remains normal and the CRP is normal or only slightly elevated, consider

causes of weight loss other than cachexia.

*Muscle mass is measured in clinical trials using a variety of methods such as DEXA scan, CT or MRI.

However, this is not practical in terms of assessing a patient in the community; loss of muscle mass can be estimated by a visual assessment.

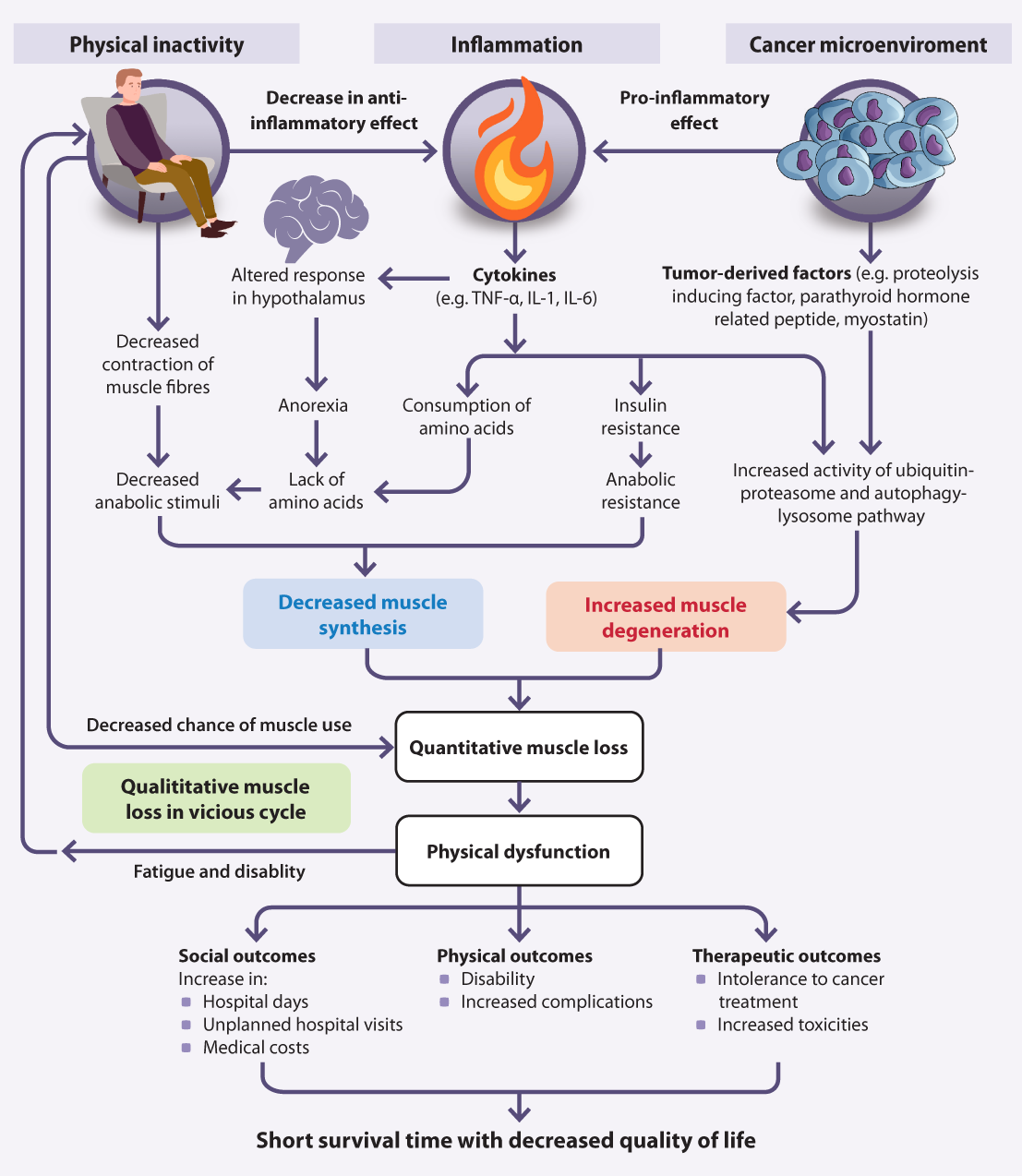

Mechanisms of cancer cachexia

Cachexia results as a consequence of multiple mechanisms (Figure 1), involving major organs, skeletal muscle, adipose

tissue, the digestive system, immune system and central nervous system.8 In people with cancer, systemic inflammation

is primarily caused by the presence of a tumour. This is then exacerbated by physical inactivity, because the natural anti-inflammatory

effect of exercise is absent and infrequent contractions of skeletal muscle (and other associated mechanisms) results in

less muscle synthesis.8 Increased levels of cytokines results in insulin resistance, and ghrelin resistance

results in loss of appetite and anorexia. Concurrent muscle degeneration also occurs due to direct tumour effects.8

The mechanism results in a “vicious cycle” where reduction in skeletal muscle impairs the patient's ability to be

physically active, thereby further contributing to the muscle loss.8

Figure 1. Mechanisms and clinical outcomes of cancer cachexia. Figure adapted from Naito et al (2019).8

Effective management of cachexia can help to avoid early termination of cancer treatment; an effective cancer treatment regimen improves cachexia.6

The management of cachexia is dependent on the patient’s individual clinical circumstances and their treatment goals and

beliefs. Caloric supplementation is not able to reverse cachexia, however attention to nutrition is vital, to slow the rate

of decline. Treatment focuses on symptom palliation and optimising quality of life.5 A multi-modal approach combining

nutritional, pharmacological, physical and psychosocial management is preferred.14, 15

A cachexia diagnosis, and its significance, can be difficult to accept for patients with cancer, their families/whānau

and other caregivers as it is often associated with a poor prognosis, and may be deemed as a sign of imminent death.1 Loss

of appetite and appearance changes as a result of cachexia may be particularly upsetting; acknowledging this distress is

important, and referring for psychosocial counselling or to a cancer support group may be helpful.

One of the biggest impacts primary care can have is on educating the patient and their family/whānau that cachexia is

an expected part of terminal cancer progression, and there are multiple factors outside of the patient’s control as to why

it occurs; it is not simply a consequence of a lack of food or eating. Conflicts in families around food can be destructive

and directly affect patients’ quality of life (see “Mental health and wellbeing”).

Healthcare professionals, patients or their families/caregivers can make a referral to the Cancer Society

for support and assistance: www.cancernz.org.nz

Nutritional interventions

First consider and treat (if possible) any reversible exacerbating causes of nutritional issues, such as mucositis, candidiasis,

constipation, nausea and vomiting.16

Weight loss cannot usually be reversed by increasing calorie intake alone, due to the distinction between the mechanisms

of cachexia and starvation. However, optimising nutritional intake has many other benefits, such as potentially slowing

the rate of progression of cachexia and improving quality of life due to the psychosocial aspects of eating.

The following points may be helpful when discussing nutrition:1, 12, 16

- Encourage the patient to eat what they want, when they feel like it, rather than just at traditional mealtimes; suggest

frequent, small, calorie dense meals – ideally a variety of nutritionally balanced foods will be chosen, but any food is

better than none. Consider ways to improve palatability and presentation of meals, e.g. adding sauces or using a small

side plate (so the portion size seems more manageable and not “lost” on the plate).

- If patients are unable to increase the volume/calories of food they eat, emphasise the social benefits of eating with

family and friends, e.g. seated at a dining table, and the pleasure of tasting favourite foods

- Encourage involvement of the family/whānau and caregivers as often as possible, e.g. in preparing meals and eating together.

Discuss that patients may have a changed sense of smell or taste and relay the importance of avoiding strong cooking smells

as they can trigger nausea.

- There is no evidence that extreme diets or diets based on food group exclusions, such as ketogenic, vegan, alkaline

and macrobiotic, have any beneficial effect in patients with cachexia

- Referral to a dietitian may be useful to devise a plan for the patient to meet protein and energy requirements, and

to provide evidence-based information on specific diets

- Suggest that the patient does not closely monitor their weight if this is causing them distress or anxiety

Nutritional information for people with cancer is available at: https://www.cancer.org.nz/cancer/living-with-cancer/eating-well-with-cancer/

Adding supplemental nutrition

An oral liquid feed, e.g. Ensure powder (fully funded with Special Authority approval), may be useful

to supplement meals and increase overall calorie intake. In practice, dieticians tend to recommend fortified smoothies using

Ensure powder, as many patients cannot tolerate the full amount of the supplemental drinks nor have the energy or support

to make them up.

A recent systematic review concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend any particular vitamin or

mineral supplements for patients with cachexia.17 It is preferable to optimise dietary intake of essential

vitamins and minerals before considering supplementation. For example, oily fish such as salmon contains omega-3 fatty

acids, nuts and wholegrains are a source of magnesium and arginine, and avocado and liver contain vitamin B3. However,

eating these types of foods, and in adequate quantities, may not be possible, and therefore a multivitamin supplement may

be considered. The systematic review did not find any evidence of serious adverse effects of taking a supplement.17

Complementary and alternative medicines and “dietary” supplements are not recommended in general as they

can interact with conventional medicines the patient is taking and worsen their clinical status.12 However, it

is important to be respectful of the patient’s wishes and beliefs and ask about specific products they are taking and consider

whether they are causing harm. For example, Rongoā Māori (traditional plant-based healing) can often be used alongside conventional

treatment.

Parenteral and enteral feeding tubes are not routinely recommended in people with cachexia; parenteral

nutrition may be used in severe cases in select patients, e.g. with bowel obstruction.12

Mental health and wellbeing

Experiencing cancer cachexia has emotional and social impacts for patients and their families/whānau, including loss of

independence, feelings of helplessness, failure and blame, conflict over eating, social isolation, loss of dignity, pride

in appearance and self-confidence, fear and thoughts of death.18 This can cause a significant amount of distress.

Identifying these issues early and providing solutions can help people cope better, and it may also increase compliance

with treatments, which in turn improves quality of life.18, 19

Ask questions such as: “how do you feel about not being able to eat?” and “how do you feel about the changes to your body”

to uncover underlying mental health and wellbeing concerns.19 Interventions may include education about why and

how cachexia occurs, setting realistic expectations (e.g. aiming to slow weight loss rather than to gain weight), tailored

advice about dealing with a particular situation (e.g. pressure from family members to eat meals they have prepared), and

strategies for enhancing coping and resilience skills (e.g. acceptance of eating limitations and inevitability of decline).19

A key point for both patients and their carers to understand is that lack of desire to eat and weight loss is not controllable

in cachexia, and it is not the patient’s fault that this is happening, nor is it a consequence of the carers not providing

adequate support. The following points may also be helpful:19

- Enhance the social aspects of mealtimes, e.g. enjoyment of sitting together at the dining table

- Shift the focus from eating to other activities that create happiness or satisfaction

- Ask carers to find other ways to provide support, e.g. making the patient physically comfortable, creating a relaxing

environment, talking, hugging or holding hands, massage

For patient and family/whānau specific support services and information, see: https://www.healthnavigator.org.nz/health-a-z/p/palliative-care/palliative-care-appetite-loss/

Physical activity

For many patients with cancer cachexia, the capacity to undertake exercise is likely to be limited. However, as inactivity

is part of the mechanism that underlies the progression of cachexia, any physical activity is likely to be beneficial. Exercise

is thought to lessen the decline in cachexia by preserving muscle mass and function and reducing systemic inflammation and

catabolism.4, 12 Specific exercise goals are not currently recommended in guidelines due to insufficient evidence,

however, it is unlikely to cause harm when undertaken; if the patient feels physically capable of keeping active then they

should be encouraged to do so.

For information on keeping active when living with cancer, see:

https://www.cancer.org.nz/cancer/living-with-cancer/being-active/

Clinician’s Notepad: cachexia

Assessment and diagnosis

- Measure weight, BMI, assess musculature and strength

- Check for oral issues

- Request CRP, lipids, HbA1c, FBC and LFTs

Diagnose cachexia if ≥ 5% loss of body weight or BMI ≤ 20 kg/m2 and three or more of: decreased

strength, fatigue, anorexia, low muscle mass, raised CRP and reduced albumin or Hb.

Management

- Importance of patient + family/whānau understanding that cachexia is not just a lack of food/eating

- Treat any mucositis, candidiasis, constipation, nausea and vomiting

- Recommend frequent, small, calorie dense meals + discuss strategies for enhancing nutrition/mealtimes

- Consider mental health and wellbeing

- Recommend as much physical activity as tolerated

Pharmacological treatments

- Oral liquid feed, e.g. Ensure powder, as meal supplement

- If shorter life expectancy, dexamethasone 2 – 4 mg or prednisone 30 mg, in the morning, adjusted to the lowest effective

dose; beneficial effect on appetite likely to decrease after 3 – 4 weeks, discontinue if no benefit after five days

- If longer life expectancy, megestrol 160 – 800 mg, daily; beneficial effect on appetite longer lasting than with corticosteroids

- If nausea, metoclopramide 10 mg, three times daily, ideally before meals

- Pancreatic enzyme replacement if malabsorption due to pancreatic insufficiency

The efficacy of pharmacological treatments for cachexia is minimal,1 and there is a lack of evidence to recommend

one treatment in particular to improve outcomes.12 Pharmacological treatment may result in small weight improvements

in some patients, but no significant differences are found in other important outcomes such as muscle mass, physical activity

or mortality; use of medicines is often limited by adverse effects.7 Although improving weight is the ideal end

result, maintaining weight or slowing weight loss may be a more realistic goal.

In New Zealand, the most commonly used medicines to manage cachexia are corticosteroids (e.g. dexamethasone

or prednisone) and progestogens, e.g. megestrol or medroxyprogesterone (see below for more information).16 Corticosteroids

and megestrol are equally effective, although corticosteroids are generally only used short-term, e.g. during the pre-terminal

phase of cachexia.5 Megestrol is usually recommended for people with a longer life expectancy.16

Consider trialling an anti-emetic such as metoclopramide if nausea is secondary to gastric stasis. Metoclopramide

may reduce early satiety and improve post-prandial fullness allowing increased food intake. However, there is no evidence

that this results in weight gain. Metoclopramide, 10 mg, three times daily,16 ideally before meals is particularly

helpful if a patient is taking opioids or there is autonomic neuropathy.

In patients with obstruction of the pancreas or bile duct (i.e. due to a tumour) pancreatic enzyme replacement using

pancreatin or pancrelipase can be used to treat possible malabsorption due to pancreatic insufficiency.

Limited or no evidence for other treatments

The American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines found inconclusive evidence to support the use of other pharmacological

treatments for cachexia including olanzapine, androgens, mirtazapine, NSAIDs and thalidomide; there was no evidence of effectiveness

of the use of melatonin or cannabinoids (weak recommendation against use) or TNF inhibitors (moderate recommendation against

use).12

Although not supported by evidence or guidelines (see above), some patients with cachexia anecdotally find medicinal

cannabis useful for appetite stimulation. Some medicinal cannabis products are now able to be prescribed in primary

care (see link below). Efficacy, the optimal dose and route of administration is currently unknown; the decision to prescribe

should consider benefits versus risks and a treatment plan should include objective goals and monitoring for adverse effects.

For information on prescribing medicinal cannabis, see:

https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/regulation-health-and-disability-system/medicinal-cannabis-agency/medicinal-cannabis-agency-information-health-professionals

N.B. bpacnz will be publishing a guide on prescribing medicinal cannabis within the next few months.

Corticosteroids can be used short-term

Corticosteroids are one of the most widely used medicines for cachexia where they have been demonstrated to modestly improve

appetite and quality of life.20 They may also improve nausea, leading to increased food intake. Both dexamethasone

and prednisone are subsidised in New Zealand, although use in patients with cachexia is an unapproved indication.16

The recommended regimen is dexamethasone 2 – 4 mg or prednisone 30 mg, in the morning, adjusted to the lowest effective

dose.16, 21 If there is no benefit after five days, treatment should be discontinued; onset of benefit is usually

rapid, but this effect tends to decrease after three to four weeks.16, 21

Corticosteroids are preferable in patients with a shorter life expectancy, e.g. weeks to a couple of months.12 Prolonged

use can result in diminished appetite and muscle catabolism.16 Longer-term adverse effects of corticosteroids

such as diabetes, osteoporosis and adrenal insufficiency are not generally a concern, as patients with advanced cachexia

will not survive long enough to develop these.13 Corticosteroids can elevate mood and induce euphoria which may

be beneficial for people with cachexia, however, rarely psychosis can also develop which can amplify existing distress;

inform patients of this risk and monitor for unexpected behavioural changes.16

Progestogens can be used for longer

Megestrol and medroxyprogesterone are active derivatives of progesterone used as appetite stimulants to increase caloric

intake and nutritional status. In general, patients gain a modest amount of weight through increased adipose tissue rather

than skeletal muscle.5 The effects on appetite are longer lasting than with corticosteroids, therefore it is

a preferable option for patients with a longer life expectancy, e.g. several months.12

Megestrol is the most frequently used progestogen for cachexia. In New Zealand, megestrol is subsidised, but use in cancer

cachexia is an unapproved indication.16 The recommended regimen for cachexia is megestrol 160 – 800 mg, daily.16

The use of medroxyprogesterone in people with cachexia is not indicated nor approved in New Zealand and there is no dosing

recommendation in the medicine datasheet or NZF. Medroxyprogesterone is available in 100 mg and 200 mg tablets (for oncology

treatment), however, only the 100 mg tablets are subsidised. A dose of 400 mg, daily is recommended in palliative care guidelines

from the United Kingdom;22 check for local protocols.

Main adverse effects associated with progestogens are thromboembolic events, oedema and adrenal suppression.12, 16

The role of primary care in cancer management

An ever-increasing aged population in New Zealand has given rise to a greater number of people with cancer. Improved cancer

treatments in recent years have resulted in more people living longer with cancer, growing the demand for oncology services.12 As

such, there is an opportunity for primary care clinicians to widen their involvement in the management of patients with

cancer, providing continuous, supportive, overall care throughout a patient’s cancer journey.23

When considering cancer as long-term disease management, primary care practitioners are likely to be involved in providing:23–26

- All-encompassing care across multiple areas, e.g. cancer prevention, diagnosis, shared follow-up, survivorship care and end-of-life care

- Encouragement to seek early help for symptoms or concerns

- Education and psychosocial support to patients and their families/whānau, which may include referral to community support agencies,

e.g. Māori and Pacific health providers, hospice care, counselling services

- Monitoring of patients’ haematological and biochemical status during chemotherapy or targeted therapy

- Management of adverse effects caused by medicines, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, e.g. nausea/vomiting, constipation with opioid treatment,

skin conditions

- Surveillance to detect cancer recurrence, both local and metastatic

- More conveniently located care, with oncology services often only in major cities

Individualised cancer care plans should provide clear understanding of responsibilities of care (e.g. who will follow

up test results), surveillance and monitoring expectations and criteria for re-entry back into oncology services when required.

Te Aho o Te Kahu, Cancer Control Agency, provides resources for healthcare professionals and patients in New Zealand to guide

better cancer outcomes: https://teaho.govt.nz/