Published: 18 September 2020

Kamini (also referred to as Kamini Vidrawan Ras, KVR) and Barshasha are opioid-containing herbal medicines originating from India, that are becoming increasingly

commonly seen in the community in New Zealand, despite being illegal to import, supply or possess without a prescription. A large police seizure of Kamini recently

took place in Auckland. It is likely that Kamini use is widespread among some groups, and the harm caused by it is underreported.

Since 2013, the South Auckland Unit of the Auckland Opioid Treatment Service has treated ten men addicted to Kamini, one of whom was also using Barshasha.

Most of these men had a history of oral opium use in India prior to immigrating to New Zealand. By the time of admission, all were taking excessively large doses

of Kamini, and attempts to reduce or stop led to severe opioid withdrawal symptoms. The group of men have responded well to opioid substitution treatment

(OST), but all have required higher doses of OST compared to people withdrawing from other opioids.

Primary care clinicians should be aware of the use of Kamini and Barshasha, particularly among the Indian community and followers of Ayurvedic or Unani medicine.

If patients are using these preparations, assess whether they have symptoms and signs of opioid dependence; ask them if they experience any problems when they

miss a dose or try to stop. Local Community Alcohol and Drug Services can provide assistance with patients experiencing difficulties.

‘Kamini’ and ‘Barshasha’ are opioid-containing herbal medicines that are reportedly available for purchase in the community.

Kamini comes in the form of small pellets (Figure 1), swallowed like tablets, and is purported to have a

wide range of benefits for men’s sexual functioning and overall vitality.

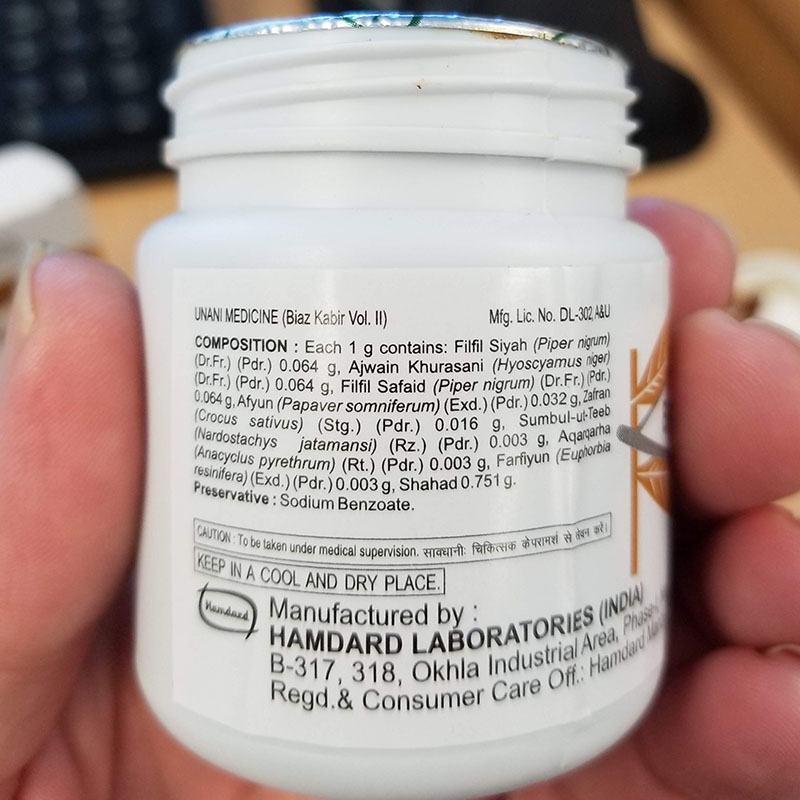

Barshasha is a paste (Figure 1), promoted as useful for a range of conditions including the common cold, low mood and sleep disturbance.

Barshasha seems to be less readily available and less palatable, reportedly causing a dry throat in some users.

|

|

|

| Figure 1: Kamini (left) comes in the form of small pellets while Barshasha is a paste

(centre). List of ingredients (right) in a barshasha preparation |

Since 2013, the South Auckland Unit of the Auckland Opioid Treatment Service has treated ten men addicted to Kamini. We remained unaware of Barshasha until

2019 when one of the ten men presented using both Kamini and Barshasha. The majority of men had a history of oral opium use in India prior to immigrating to

New Zealand. A few were introduced to Kamini in New Zealand by friends who suggested it would help them to sustain long work hours. Their main impetus for seeking

treatment was the time and money required to acquire and use these substances, with the men spending between $400-800 per week on Kamini, primarily funding this

through their own wages. This put considerable pressure on family finances and relationships. Some have been referred to opioid substitution treatment (OST) by

friends who have had a positive experience, one by his general practitioner who looks after a client on OST and, more recently, some have googled "Suboxone"

(buprenorphine + nalaxone for the treatment of opioid dependence) looking for where they could source it as it becomes more established in India and

friends there have recommended it.

The advertised Ayurvedic dose of Kamini is 0.5-1 pellet per day. By the time of admission to our service, each of the ten men in the cohort was taking between

24-36 pellets per day, usually in three divided doses. Attempts to reduce or stop had led to severe opioid withdrawal symptoms in all cases, e.g. nausea, vomiting,

diarrhoea, runny nose, runny eyes, body aches, shaking, tachycardia. A sample of Kamini provided by one of the men was sent to the Institute of Environmental

Science and Research (ESR) in 2013, which confirmed it contained opium. A sample of Barshasha, sent to ESR in 2019, did not have the appearance of opium but

was noted to contain morphine, codeine and papaverine – common constituents of opium. Significantly, all ten men required relatively high doses of OST. To

date, nine have been stabilised on buprenorphine/naloxone and required between 24 mg – 32 mg of buprenorphine, the maximum daily dose. In contrast, users

of other opioids on our programme generally stabilise on between 14–16 mg of buprenorphine per day. One man was unable to tolerate buprenorphine and was

consequently changed to 100 mg methadone. He is not yet fully stable and may require the maximum recommended dose of 120 mg.

On the whole, the cohort has done well on OST treatment. Nine men remain in treatment; seven are not using any additional opioids. Two men use 3–5 pellets once

or twice a month, due to perceived benefits of improved sexual functioning. All report OST has led to improved relationships, decreased financial stress in the

family and better functioning at work. Two report having been promoted or moved into higher paying jobs. One has ceased treatment with buprenorphine and

subsequently became alcohol dependent.

We suspect that the success of this cohort has been because they entered into treatment with significant recovery capital. The majority are employed, married

and have children. None of the ten men had a history of intravenous drug use. Most did not use any other substances (including alcohol) and were otherwise

physically well. Additional psychopathology was not prominent. This level of recovery capital is less common among the traditional illicit intravenous

drug-using community. The sociodemographic presentations seem comparable to the clients who enter our programme after developing opioid use disorders

in the context of chronic pain, which is about half of our new admissions. This ‘chronic pain’ cohort also benefits from treatment, but persisting pain

tends to limit their functional recovery compared to the Kamini and Barshasha cohort.

In addition, the harm our cohort was experiencing prior to coming into treatment was primarily socioeconomic. Long term oral opioid use confers relatively

lower physical risks than some other habit-forming medicines. While our clients experienced withdrawal symptoms if unable to afford a steady supply, on 8–12

pellets three times daily, they did not have significant issues with intoxication or sedation, likely because they were maintaining fairly steady serum levels.

Access to consistent, fully funded OST has been an effective harm minimisation approach primarily by removing the financial stress for our clients enabling

the salience of these substances in their lives to recede.

Theoretically, there are also risks related to illegality of these substances. The importation, supply and possession of Kamini and Barshasha without a prescription

is prohibited in New Zealand under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975. However, none of our cohort had received charges or convictions directly related to their Kamini or Barshasha use.

This may reflect that the focus of attention by law enforcement has been at the border. The following data, supplied by the National Drug Intelligence Bureau

New Zealand, reflects goods seized by customs at the international mail centre between 2017 and 2019.

Total annual seizures of Kamini 2017 – 2019 A B

| |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

Total |

| Grams |

4562 |

4039 |

725 |

9326 |

| Pills |

11422 |

316 |

9449 |

21187 |

A 2019 data is provisional and subject to change.

B There have been three seizures of Barshasha during this period, totalling 660 grams.

In early September, 2020, a police seizure of Kamini was made in the community in Auckland. As a result of the operation, two people have been charged with

importing and supplying opium (a class B controlled drug). Since this time, two new clients and one of the original group of men have presented to the South

Auckland OST clinic seeking assistance for Kamini dependence and reporting that they are now unable to source Kamini.

Given 50-90% of opioid-dependent clients will relapse to illicit opioid use within 12 months of weaning off OST,1 we encourage clients to remain on the lowest

effective dose of OST that allows them to function well in their lives. This usually requires reframing OST as being a medicine for a chronic condition, like insulin for a

person with diabetes. Once stable, clients can move into general practice shared care which can support greater flexibility around dosing, such as being observed to consume

their medication twice a week at the pharmacy and receiving the remainder of their medication as takeaway doses.

Adverse effects of long-term opioid treatment include constipation that can be managed with dietary modifications and laxatives. A class effect of long-term opioid use

is hypogonadism and low testosterone. As a partial opioid agonist, buprenorphine has less impact on testosterone levels than methadone or opium so an improvement in the

sexual functioning of our cohort on OST may be expected, though this has not been volunteered thus far. In men, hypogonadism can be managed with testosterone replacement

if symptomatic. Unfortunately, the treatment options for managing these difficulties in women are less well-established.

One of the most concerning risks of weaning off OST is the potential for accidental overdose. This occurs when clients relapse after a period of abstinence and does not

take into account their loss of tolerance to opioids, which occurs rapidly. Under these circumstances, a previous ‘typical’ dose can be fatal. This risk is further

increased by concurrent use of other central nervous system depressing agents such as alcohol or benzodiazepines which should also be only used with extreme caution

in the context of OST. We provide careful psycho-education to all our clients, including our Kamini cohort, about these risks.

We believe that our experiences in South Auckland are a timely reminder that herbal medications should not be assumed to be innocuous. We encourage clinicians to

ask all patients about herbal medication use and whether they experience any problems when they miss a dose or try to stop. Your local OST/community alcohol and

drug service would be of assistance with clients experiencing difficulties, particularly in those using Kamini and Barshasha.