Published: 8 June 2020 | Updated 22 February 2023

What's changed?

22 February 2023 Box added on GOLD 2023 recommendations.

22 February 2021 Updated to include new guidance from the 2021 Asthma + Respiratory Foundation NZ COPD guidelines and funding changes.

Update (2023)

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) has released a 2023 report on the prevention, diagnosis and management of COPD. It contains a number of updated recommendations, including:

- A revised “ABE” assessment tool for predicting patient outcomes and making treatment decisions. This recognises the clinical relevance of exacerbations, regardless of the patient’s symptom severity (i.e. categories “C” and “D” in the “ABCD” tool are now combined into a single “E” category).

- LABA/LAMA combination treatment is now recommended as the first-line option in patients requiring a long-acting bronchodilator, including those who are more symptomatic or at high exacerbation risk. This supersedes previous guidance to use LAMA or LABA monotherapy first.

- Use of an ICS + LABA alone is now discouraged throughout COPD management unless prescribed for a concurrent diagnosis such as asthma

Given these significant changes, we plan to update this article. However, we will await any revision of New Zealand guidelines in accordance with the GOLD 2023 report. In addition, Special Authority approval criteria for LABA/LAMA combinations currently require patients to be stabilised on LAMA monotherapy first, making these recommendations difficult to apply equitably in practice.

Key practice points:

- Non-pharmacological interventions continue to underpin COPD management, including smoking cessation, regular exercise,

pulmonary rehabilitation and annual influenza vaccination

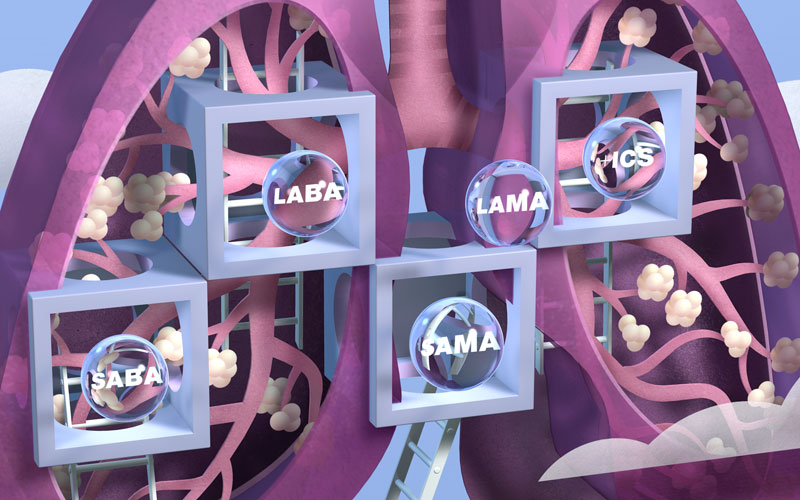

- All patients with COPD should be prescribed a short-acting bronchodilator for relief of acute breathlessness, i.e.

the short-acting muscarinic antagonist (SAMA) ipratropium or a short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA) either

salbutamol or terbutaline, or the combination SABA/SAMA salbutamol + ipratropium

- Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs), e.g. tiotropium, glycopyrronium and umeclidinium, are now recommended

as the first-line long-acting bronchodilators for patients with persistent symptoms

of COPD; long-acting beta2-agonists (LABAs) are prescribed if LAMAs are contraindicated or not tolerated,

whereas previously LABAs were first-line with LAMAs.

- Combination LABA/LAMAs are recommended for patients with persistent or troubling symptoms or whose lung function

has declined significantly or who continue to experience exacerbations, despite LAMA or LABA monotherapy

- Triple therapy, i.e. a LABA/LAMA + an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), may be appropriate for patients who have experienced

two or more exacerbations in a year

- A blood eosinophil count may help predict which patients with COPD are most likely to benefit

from ICS treatment; levels ≥ 0.3 x 109/L are associated with the greatest likelihood of benefit, levels < 0.1

x 109/L the least benefit. Spirometry is no longer recommended to guide the use of ICSs.

- It is now clearer when withdrawal of ICS treatment may be beneficial, i.e. where there is no evidence of benefit,

the patient develops pneumonia or if they are clinically stable without a history of recent exacerbations

N.B. Information on aspects of care not covered in this article such as patient education, COPD action plans, nutritional

guidance, exacerbation management, treatment of advanced symptoms and end-of-life care is available

from: “The

optimal management of patients with COPD – Part 2: Stepwise escalation of treatment” and the

Asthma

+ Respiratory Foundation NZ COPD guidelines (2021)

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterised by persistent respiratory symptoms and an airflow limitation

caused by noxious exposure to particles or gases.1 It is estimated to be the fourth leading cause of death

in New Zealand, following ischaemic heart disease, stroke and lung cancer.2

The exact prevalence of COPD in New Zealand is unknown. It has been conservatively estimated that one in every 15

people aged over 45 years has COPD, with a substantial number of additional people with undetected early-stage disease.3

COPD is associated with significant health disparities. Hospitalisation rates due to COPD are over five times higher

for people living in the most deprived quintile, compared to people living in the least deprived quintile.4 Māori

have COPD hospitalisation rates that are 3.5 times higher and COPD mortality rates 2.2 times higher, than people of

non-Māori, Pacific or Asian ethnicity.4 Early investigation and diagnosis of COPD, combined with optimal

management is critical in reducing these disparities in the most affected communities.

Diagnosis, assessment and non-pharmacological management

A diagnosis of COPD is typically based on the following factors, particularly

in patients aged over 40 years:1, 5

- Breathlessness on exertion, cough and sputum production

- Long-term exposure to tobacco smoke or noxious exposure to respiratory irritants, e.g. pollution, occupational

chemicals or unventilated cooking fires (more common in immigrants from less developed countries)

- Post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC* < 0.70 on spirometry

* FEV1 = Forced expiratory volume in 1 second, FVC = forced vital capacity

Further information on COPD diagnosis is available from:

https://bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2015/February/copd-part1.aspx

Assess COPD severity with spirometry and by the level of symptoms the patient is experiencing at

diagnosis and review annually to measure progression. The COPD Assessment Test (CAT) is a short eight-item tool that

provides a broad assessment of the patient’s quality of life, e.g. sputum production, sleep quality and confidence

in leaving their home, on a scale of zero to 40 (most severe). The Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea

scale is a brief assessment of functional disability that determines the impact of breathlessness on the patient’s

daily life.1 The CAT and mMRC can both be useful when assessing COPD in primary care.1

The CAT and mMRC are available from: www.catestonline.org/patient-site-test-page-english.html and

the CAT is also available in Appendix 2 of the NZ COPD guideline, found here: https://www.nzrespiratoryguidelines.co.nz/copdguidelines.html

Non-pharmacological interventions are first-line in COPD management as they are the most effective

way to improve symptom control and quality of life and modify disease progression, regardless of what pharmacological

treatments are ultimately required. Non-pharmacological interventions include:1, 5

- Smoking cessation; the most important factor to improve symptoms and slow disease progression

- Regular exercise; at least 20 – 30 minutes per day, ideally more if fitness allows

- Weight loss for people who are obese; adequate nutrition for those who are malnourished

- Pulmonary rehabilitation; offered to all patients, where available as it improves breathlessness substantially

more than inhaled medicines (see Appendices 4 and 5 of the NZ COPD guidelines for some non-pharmacological

strategies for breathlessness:

https://www.nzrespiratoryguidelines.co.nz/copdguidelines.html)

- Creating a written COPD action plan indicating what to do if the patient’s condition deteriorates – an example plan is provided in

Appendix 3 of the NZ COPD guideline https://www.nzrespiratoryguidelines.co.nz/copdguidelines.html

- Annual influenza immunisation and appropriate pneumococcal immunisation reduces the risk of serious respiratory

infections and COPD exacerbations*

* People with COPD are eligible for a funded influenza vaccination but not a funded pneumococcal

vaccine. If affordable to the patient, it is recommended they receive both PCV13 and Pneumovax23 (see Immunisation

Handbook for further details)

Further information on smoking cessation is available from: https://bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2015/October/smoking.aspx

Further information on pulmonary rehabilitation is available from: https://bpac.org.nz/2017/copd.aspx

A stepwise approach guides the use of inhaled medicines in the management

of patients with stable COPD, taking into account:1, 5

- Symptom severity

- Exacerbation frequency

- Patient preference for medicine and inhaler type, e.g. some patients may find manipulating certain inhaler types

difficult

- Likelihood of experiencing adverse effects

- Regimen complexity

Check the patient’s treatment adherence and inhaler technique at each consultation, and especially

before making changes to their treatment regimen. This can also be done by community pharmacists; consider adding a

note to the prescription asking the pharmacist to check the patient’s technique.

New version of the bpacnz COPD prescribing tool now available

The bpac

nz COPD prescribing tool has been updated and now includes

a second clinical resource. The tools present pharmacological treatment options

for patients with COPD based on their symptoms and exacerbation severity; the first tool is used

for

treatment

initiation and the second tool is used

for the

escalation or de-escalation of treatment. These resources have been developed following the

publication of guidelines by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease

(

GOLD 2020) and the Asthma

+ Respiratory Foundation NZ (

NZ

COPD guidelines 2021).

All patients with COPD require inhaled medicines. Alongside non-pharmaceutical interventions, medicines improve symptoms,

exercise tolerance and quality of life and may reduce the frequency and severity of COPD exacerbations.1,6 There

is, however, no conclusive evidence that medicines can prevent the long-term decline in lung function associated with

COPD.1

Bronchodilator treatment regimens need to be individualised as the effect is often difficult to predict.1 Inhaled

medicines are initiated as therapeutic trials and the patient’s response monitored; a different inhaler or class of

bronchodilator can be prescribed if the treatment response is not sufficient, after checking adherence and inhaler

technique. Table 1 provides updated recommendations on the use of inhaled medicines for patients

with COPD including initiating LAMAs at Step 2, in preference to LABAs, and the use of blood eosinophil levels to guide

the use of ICSs.

Table 1: The stepwise escalation of pharmacological treatment for COPD, based on disease severity,

adapted from the Lung Foundation Australia (2018) to include GOLD and Asthma + Respiratory Foundation

NZ guidance (2021)1,6,7

| Severity |

MILD |

MODERATE |

SEVERE |

|

- Few symptoms

- Breathless on moderate exertion

- Little or no effect on daily activities

- Cough and sputum production

- FEV1 typically ≈ 60–80% predicted

|

- Breathless walking on level ground

- Increasing limitation of daily activities

- Recurrent chest infections

- Exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids and/or antibiotics

- FEV1 typically ≈ 40–59% predicted

|

- Breathless on minimal exertion

- Daily activities severely restricted

- Exacerbations of increasing frequency and severity

- FEV1 typically < 40% predicted

|

| Medicine management

|

CHECK device technique and adherence at each visit and

reiterate the importance of smoking cessation, regular exercise and pulmonary rehabilitation, as appropriate. |

| Step 1: START with a short-acting inhaler for as needed use,

e.g. salbutamol, terbutaline, ipratropium or the combination salbutamol + ipratropium. |

Step 2: ADD a LAMA e.g. tiotropium, glycopyrronium

or umeclidinium, or a LABA, e.g. salmeterol, indacaterol or formoterol, as an alternative.

Step 2a: CONSIDER the need for a combination LABA/LAMA,

e.g. indacaterol/glycopyrronium, vilanterol/umeclidinium or olodaterol/tiotropium,

depending on the patient’s symptoms; patients with an eosinophilic pattern of disease (see below) may benefit

from ICS/LABA instead of LABA/LAMA. |

|

Step 3: CONSIDER adding an ICS, e.g. fluticasone* (furoate or propionate) or

budesonide: triple therapy may be appropriate for patients with = 1

exacerbation requiring hospitalisation or = 2 moderate exacerbations in

the previous 12 months, AND significant symptoms despite LABA/LAMA

or ICS/LABA treatment. Patients with a blood eosinophil count = 0.3 ×

109/L are most likely to benefit from ICS treatment; patients with a blood

eosinophil count < 0.1 × 109/L are least likely to benefit. |

The updated bpacnz COPD prescribing tool can be used to select medicines and inhaler types

based on the patient’s symptom severity and preference, available from: https://bpac.org.nz/copd-tool

Step 1: Prescribe short-acting bronchodilators to control occasional symptoms

Continue prescribing short-acting bronchodilators to all patients with COPD for

the relief of acute breathlessness.1 The following medicines all provide short-term improvements in breathlessness

for patients with occasional symptoms of COPD:1, 5

- Short-acting muscarinic antagonist (SAMA), ipratropium

- Short-acting beta2-agonists (SABAs), salbutamol or terbutaline

- Combination SABA/SAMA, salbutamol + ipratropium

Ipratropium produces greater improvements in lung function than SABA monotherapy and is generally better tolerated.5

The frequent use of short-acting bronchodilators, e.g. more than four times daily, is not recommended and if this

is occurring, a long-acting bronchodilator should be initiated.1

For easy reference, Table 2 provides the trade names for inhaled medicines funded for COPD treatment.

Table 2: Inhaled medicines funded in New Zealand for the treatment of COPD, by class and trade name

| Class |

Medicine |

Trade name |

| Short-acting bronchodilators |

|

|

| Short-acting muscarinic antagonist (SAMA) |

Ipratropium |

Atrovent |

| Short-acting beta2-agonists (SABAs) |

Salbutamol |

Respigen, SalAir, Ventolin* |

| Terbutaline |

Bricanyl |

SABA/SAMA combination |

Salbutamol + ipratropium |

Duolin HFA † |

| Long-acting bronchodilators |

|

|

| Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) |

Glycopyrronium †† |

Seebri |

|

Tiotropium †† |

Spiriva, Spiriva Respimat |

|

Umeclidinium †† |

Incruse Ellipta |

| Long-acting beta2-agonists (LABA) |

Formoterol |

Foradil*, Oxis * ¤ |

|

Indacaterol |

Onbrez |

|

Salmeterol |

Serevent |

| LABA/LAMA combinations |

Indacaterol/glycopyrronium |

Ultibro Breezhaler** |

|

Olodaterol/tiotropium |

Spiolto Respimat** |

|

Vilanterol/umeclidinium |

Anoro Ellipta ** |

| Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) |

|

|

| ICS/LABA combinations |

Budesonide + formoterol |

Symbicort, Vannair |

| Fluticasone (furoate) + vilanterol |

Breo Ellipta |

| Fluticasone (propionate) + salmeterol |

Seretide |

| ICS‡ |

Budesonide |

Pulmicort |

| Fluticasone |

Flixotide |

*Partly funded

†As of February, 2021, there was an ongoing supply issue with

Duolin. Stock ran out at the end of 2020 and a re-supply date has not been confirmed. Patients can be prescribed two

inhalers, i.e. a salbutamol 100mcg inhaler and an ipratropium bromide 20mcg inhaler (Atrovent). Check the PHARMAC

website for latest updates on supply.

†† Subsidised by endorsement for patients who have been diagnosed as having COPD by spirometry. Patients

who had tiotropium dispensed before 1 October, 2018 with a valid Special Authority are deemed endorsed.

**Special Authority funding for initiation requires patients

be stabilised on a LAMA and that they are likely to receive additional benefit from a combination inhaler. Special

Authority renewal requires that patients be adherent to treatment and the prescriber considers that they have improved

symptom control.

¤ Each delivered dose of Oxis 6 Turbuhaler contains 4.5 micrograms per dose. The corresponding metered dose contains 6 micrograms eformoterol.

‡ICS inhalers should be prescribed alongside a LABA/LAMA in patients with

COPD (unapproved indication)

Step 2: Add a long-acting bronchodilator for persistent breathlessness

Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) are now first-line at Step 2 for

patients with continuous COPD symptoms or frequent exacerbations, despite regular and correct use

of a short-acting bronchodilator, if they meet the endorsement criteria for: 5,6

- Glycopyrronium

- Tiotropium

- Umeclidinium

This is a change in guidance that has occurred in recent years as previously there was insufficient evidence to recommend

one class of long-acting bronchodilator over another. LAMAs improve symptoms and quality of life

and are associated with greater reductions in exacerbation rates and possibly fewer adverse effects,

compared to LABAs.1,6

If LAMAs are contraindicated, however, a LABA will help to reduce COPD symptoms and may also improve lung function

and patient quality of life.5

N.B. Concurrent treatment with an ICS is not needed in patients with COPD (without features of asthma) who are taking

a LABA. Combined ICS/LABA treatment is essential in patients with asthma due to the increased mortality risk associated

with LABA monotherapy.

Ipratropium should be withdrawn before initiating a LAMA and a SABA prescribed for as-needed symptom

relief. Explain to patients that a SAMA and a LAMA should not be taken concurrently. A SABA may be prescribed to patients

taking a LABA, e.g. salmeterol, indacaterol or formoterol. Ipratropium may continue to be used for occasional symptom

relief by patients taking a LABA.

It is not necessary to trial a short-acting bronchodilator before initiating a long-acting bronchodilator;1,

5 SABA-induced tachyphylaxis does not occur in people with COPD, therefore in contrast to asthma, trialling

a short-acting inhaler is not predictive of the patient’s tolerance to a long-acting medicine. If a patient has previously

been taking a short-acting bronchodilator, the initiation of a long-acting inhaler aims to decrease the need for the

short-acting inhaler.

Step 2a: Prescribe a combination long-acting bronchodilator if monotherapy is not effective

For patients with persistent or troubling symptoms, e.g. CAT score ≥ 20, or

whose lung function has declined significantly or who continue to experience exacerbations, despite LAMA

or LABA monotherapy, one of the following combination LABA/LAMAs is recommended for those meeting

Special Authority criteria:1,5,6

- Indacaterol/glycopyrronium

- Olodaterol/tiotropium

- Vilanterol/umeclidinium

Combination LABA/LAMAs may improve lung function and reduce symptoms and exacerbations more than LAMA or LABA monotherapy.1,5 LABA/LAMA combinations are generally preferred to ICS/LABA combinations due to the increased risk of pneumonia

associated with ICS treatment (see: “ICS use and pneumonia risk in patients with COPD“).1, 5

Step 3: Reserve ICS treatment for patients with exacerbations and eosinophilic COPD

An eosinophilic pattern of COPD may help to predict which patients may

receive more benefit from an ICS/LABA, e.g. fluticasone (furoate) + vilanterol, budesonide + formoterol

or fluticasone (propionate) + salmeterol compared

with a LABA/LAMA.1 Those most likely to benefit include patients

with:1

Patients with a blood eosinophil count < 0.1 x 109/L are least likely to benefit from an ICS/LABA (see:

“Use an eosinophil count and exacerbation history to determine ICS benefit”).1 Previously,

exacerbation history and spirometry to assess reversibility were used to determine which patients were likely to benefit

from an ICS.

Weigh the potential benefits of long-term ICS treatment against the risks of adverse effects, including

oral candidiasis and hoarseness, skin bruising and pneumonia.5,6 There is less robust evidence that ICS

treatment is also associated with decreased bone density and increased fracture risk, an increased risk of diabetes

and reduced glycaemic control in patients with diabetes, cataracts and mycobacterial infection, including tuberculosis,

although, the risk is substantially lower than that associated with oral corticosteroids.6 Localised adverse

effects such as oral candidiasis and hoarseness may be prevented by using a spacer with metered dose inhalers (MDIs)

and by oral rinsing following actuation.

Use an eosinophil count and exacerbation history to determine ICS

benefit

A patient’s blood eosinophil count may indicate the degree to which treatment with an ICS is likely to prevent future

exacerbations.1 The relationship between blood eosinophil counts and the protective effect of ICS treatment

is continuous and increases from < 0.1 x 109/L, where no or very little benefit is likely, to > 0.3

x 109/L where patients are likely to gain the greatest benefit.1

Exacerbation history is, however, the strongest predictor of exacerbation risk and the decision to initiate an

ICS requires the patient’s exacerbation history to be known.6 A blood eosinophil count therefore guides

treatment, rather than being an absolute marker. A blood eosinophil count is unlikely to be helpful in a patient

who has been recently diagnosed with COPD or in a patient without a history of exacerbations. Furthermore, the

risk factors for exacerbations are not completely understood and other elements such as smoking history and genetics

are also likely to contribute.6

Blood eosinophil counts are relatively reproducible, but in patients with elevated levels fluctuations are more

common and a single test may not be representative.1 A second confirmatory eosinophil count in ten to

14 days is often performed in patients with high counts, prior to initiating an ICS; a single blood eosinophil

count is sufficient in patients with low eosinophil levels. Patients taking oral corticosteroids should not undergo

blood eosinophil counts to guide ICS treatment decisions as the results will not be representative of their underlying

condition.

Triple therapy may be appropriate for patients with severe COPD

Patients who have experienced two or more exacerbations in a year or one exacerbation requiring hospitalisation or

those who are severely symptomatic, while taking a LABA/LAMA or ICS/LABA may benefit from triple therapy, i.e. LABA/LAMA + ICS.1,6 A

beneficial response to an ICS may be expected to occur in patients with a blood eosinophil count > 0.1 x 109/L

and greater improvements are more likely as eosinophil numbers increase.1,6 The potential benefit of triple

therapy, however, needs to be balanced against the increased risk of pneumonia associated with long-term ICS use.1

When to consider withdrawal of ICS treatment

In recent years it has become clearer when withdrawal of ICS should be considered, i.e. if the patient:1

- Shows no evidence of benefit after eight to 12 weeks and does not have a history of exacerbations

- Develops pneumonia or another ICS-related adverse effect

- Is clinically stable and does not have a history of frequent exacerbations, i.e. less than two moderate exacerbations

or one exacerbation requiring hospitalisation per year

Closely monitor symptom severity and exacerbation frequency following ICS withdrawal; review patients four to six weeks after stopping ICS to assess for

worsening of symptoms.1,5 There is an increased risk of exacerbations following ICS withdrawal in patients with a blood eosinophil

count > 0.3 x 109/L,1 and ICS withdrawal may not be appropriate for these patients.

In summary: regular assessment is crucial to optimise treatment

Non-pharmacological interventions (especially smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation) remain the most effective

tools in the management of stable COPD. Inhaled medicines, however, provide an important additional level of symptom

control; assess the patient’s adherence and inhaler technique at every consultation. The key recent changes concerning

the use of inhaled medicines for patients with COPD include:

- LAMAs are recommended as the first-line long-acting bronchodilators, whereas previously LABAs were first-line with

LAMAs

- Blood eosinophil levels are recommended to help predict which patients are most likely to benefit from ICS treatment

- Clearer guidance is now available for when withdrawal of ICS treatment may be beneficial

Any changes to the patient’s treatment should be accompanied by meaningful assessment, e.g. what is the effect on

the patient’s COPD assessment test (CAT) score? Any improvements in symptoms should be expected within six weeks. Positive

effects on exacerbation frequency require longer to become apparent, i.e. six to 12 months.

Further information on the selection and use of inhaler devices in COPD is available from the Goodfellow

webinar: www.goodfellowunit.org

ICS use and pneumonia risk in patients with COPD

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are potent anti-inflammatory medicines that may reduce the duration, frequency

and severity of COPD exacerbations.5 As they have a non-specific mechanism of action, ICSs also have

the potential to compromise immunity, increasing the risk of respiratory infection and other adverse effects.

The use of ICS in patients with COPD is consistently associated with an approximate 1.5-to two-fold increased

risk of developing pneumonia, depending on the dose.5, 8 This increased risk of pneumonia is, however,

not associated with an increased risk of pneumonia-related mortality or overall mortality, i.e. patients are more

likely to develop pneumonia but there is no increased risk of death.5

Discontinuation of ICS treatment in patients with COPD rapidly attenuates the elevated risk of pneumonia. A large

nested cohort study of more than 100,000 people with COPD treated with an ICS found a 37% decrease in the rate

of serious pneumonia following ICS discontinuation.9

Asthma COPD overlap is managed with an ICS/LABA

COPD and asthma are both obstructive pulmonary diseases, but they differ in many ways, i.e. aetiology, inflammatory

mediators and patterns of inflammation, treatment response and disease progression. Despite these differences,

most people with COPD will display some degree of airflow limitation reversibility and some also have an inflammatory

pattern of disease similar to asthma.5 Furthermore, some people with asthma develop an airflow obstruction

similar to COPD.5 These mixed features can make it difficult to distinguish between COPD and adult onset

asthma in people with a history of smoking. Approximately 27% of people with COPD also have features of asthma

and this is referred to as Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS).10 People with ACOS have a higher exacerbation

rate than people with COPD alone.5

ACOS should be suspected in patients where FEV1 increases by more than 400 mL on

spirometry following bronchodilation,5 particularly if they have been diagnosed with asthma before age

40 years, they have a history of smoking (> 10 pack years) or comparable exposure to air pollutants and/or blood

eosinophil count > 0.3 x 109/L.1

An ICS/LABA is generally prescribed as the first-line long-term inhaled treatment for patients

with ACOS. A LAMA is often added, i.e. triple therapy, for patients who experience persistent breathlessness or

exacerbations1. LABA monotherapy should be avoided in patients with ACOS because it is associated with a small but

significantly increased risk of mortality in people with asthma.11 ICS monotherapy is also not recommended

for patients with ACOS.

Treatment recommendations for patients with ACOS are largely derived from expert opinion as patients with ACOS

are often excluded from clinical trials involving COPD or asthma.