Carbon monoxide is produced by combustion of fossil fuels such as liquid petroleum gas (LPG), diesel and petrol, as

well as other combustible materials such as wood and paper. Exposure can occur from a range of activities involving heating,

cooking and transport, particularly if appliances are not correctly ventilated, are faulty or poorly maintained (Table

1). The use of appliances in an inappropriate manner, such as moving a barbecue inside or using a gas oven for heating,

is also a cause of exposure. Carbon monoxide cannot be detected by smell, taste or irritation of the airways, therefore

people can be unaware of exposure, particularly if the symptoms are not severe enough to be recognised as an acute poisoning

event.1

Table 1: Potential sources of exposure to carbon monoxide6, 7

| Potential source |

Precautions to prevent exposure |

- Un-flued fuel heaters, e.g. LPG, wood or charcoal

- Portable, un-flued gas cookers, e.g. for camping

- LPG-powered fridges without venting, e.g. in caravans

- Diesel generators or diesel or petrol-powered machinery used indoors, in an attached garage or with exhaust entering

an open window

- Running a vehicle in an enclosed garage, particularly if attached to a house

- Using petrol or diesel chainsaws or cutting equipment or welding in confined spaces

- LPG powered forklifts or platforms, particularly if used in poorly ventilated spaces such as cold storage rooms

- Working on fossil fuel powered vehicles or machinery, e.g. a car mechanic

- Inhalation of smoke from a fire, e.g. bonfires or burn-offs

|

These sources normally produce carbon monoxide and require adequate ventilation to prevent exposure |

- Gas or wood burning for heating or cooking:

- Open fireplaces or wood burners

- Flued LPG gas fires

- Flued gas cookers or gas ranges with rangehoods

- Pellet fires

- Outdoor barbecues

- Boilers or central heating systems

- Kilns

- Vehicles with faulty exhaust systems or with a blockage in the exhaust, such as snow or mud from driving off-road

|

These sources are typically associated with little risk but can result in exposure if equipment is faulty, poorly

maintained or used improperly, e.g. a BBQ or patio heater used indoors, a gas oven used with the door open for heating |

- Cigarette smoking

- Waterpipe (hookah) smoking, which results in more carbon monoxide exposure than cigarette smoking8

|

These activities involve inhaling carbon monoxide and quitting or smoking less is the only way to reduce exposure |

High levels of carbon monoxide exposure requires emergency management

Exposure to moderate to high levels of carbon monoxide can rapidly cause severe symptoms and progress to fatality, due

to hypoxia and other factors associated with carbon monoxide poisoning (see: “Effects of carbon monoxide

poisoning”). In New Zealand, carbon monoxide exposure resulted in 379 deaths from 2006 to 2014, with 96% of these

intentional exposures.2 The severity of carbon monoxide poisoning depends on the level and duration of exposure,

although some people are more susceptible than others.

People who are particularly vulnerable to the effects of carbon monoxide poisoning include:3

- Infants and children, due to a higher respiration rate for their body mass

- Pregnant females

- Older people with frailty

- Those with co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory conditions or anaemia

Carbon monoxide is inhaled in cigarette smoke, and people who smoke appear to have an increased tolerance to carbon

monoxide exposure, with fewer symptoms until higher concentrations are reached.4

For further information, see: “Emergency management of carbon monoxide poisoning”

Effects of carbon monoxide poisoning

When a person is exposed to carbon monoxide, it binds to haemoglobin with an affinity of over 200 times that of oxygen,

resulting in the formation of carboxyhaemoglobin.4 This prevents oxygen binding to haemoglobin and reduces

oxygen delivery to tissues, resulting in hypoxia.

It is thought that carbon monoxide poisoning also involves other processes, including directly affecting the brain and

heart. A range of mechanisms have been proposed such as diffusion of carbon monoxide into tissues, free radical formation

and disruption of critical proteins such as myoglobin and mitochondrial oxidases.9,10 Carbon monoxide is

also produced naturally in the body during the metabolism of haemoglobin, and it is possible that carbon monoxide poisoning

may interfere with the normal biological signals linked to this endogenous carbon monoxide.11

People with acute carbon monoxide poisoning are at increased risk of a range of delayed neurological sequelae, which

occur in the weeks following exposure.12 These include hearing loss, impaired concentration, depression,

difficulties with language or memory, or gait and co-ordination problems.9, 12 People who lose consciousness,

have a greater severity or duration of exposure or are of an older age (e.g. aged over 40 years) are at greater risk of

neurological complications.13 These may improve over the course of months, but may be permanent depending

on the extent of underlying injury.14

Emergency management of carbon monoxide poisoning

For patients with moderate to severe symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning, a diagnosis can be made relatively quickly

due to the sudden onset of severe symptoms, a probable source being readily apparent, occupants of the same area all being

affected and carboxyhaemoglobin testing in secondary care. In emergency situations, oxygen treatment (below) is typically

initiated prior to carboxyhaemoglobin results being available, with levels used to confirm a diagnosis.10 The

severity of symptoms is the key factor in treatment decisions, as the extent of elevation of carboxyhaemoglobin levels

correlates poorly with symptom severity, and may give a falsely low reading due to delays between exposure and blood sampling.27

Supplemental oxygen is the key treatment for acute poisoning. In the absence of treatment, the half-life

of carboxyhaemoglobin is approximately five hours. With 100% oxygen at normal atmospheric pressure the half-life of carboxyhaemoglobin

is reduced to approximately 90 minutes.9 Hyperbaric oxygen treatment reduces the half-life of carboxyhaemoglobin

to approximately 20 minutes and is recommended in some circumstances, such as for patients with severe symptoms or who

are pregnant.9 Treatment with oxygen is typically continued until immediate symptoms have resolved, with

a treatment time of six hours often used.10

Lower levels of carbon monoxide exposure may go unnoticed

It is uncertain how many people are exposed to non-fatal levels of carbon monoxide, as not all exposures are recognised

or reported, and some people do not seek treatment or receive a diagnosis.

Depending on the specific circumstances, low level repeated exposure to carbon monoxide may result in a combination

of both acute and chronic symptoms (Table 2).4 There is little evidence available regarding

the long-term health effects of this type of exposure. Patients may have a complete resolution of symptoms once the source

is discovered and removed.4 However, in some instances repeated low level exposure has caused underlying neurological

damage resulting in permanent symptoms.5 People who are unknowingly being exposed are also at risk of a potential

fatal or severe poisoning event if the level of exposure increases.

Table 2: Symptoms of exposure to carbon monoxide. Adapted from Ashcroft et al.4

| Acute exposure, i.e. short-term inhalation of moderate to high concentrations |

Chronic exposure, i.e. repeated exposure to lower concentrations |

- Headache

- Tiredness

- Nausea and vomiting

- Abdominal or chest pain

- Shortness of breath

- Delayed neurological symptoms†

|

- Memory difficulties

- Fatigue

- Mood changes

- Hearing loss*

- Ataxia, coordination difficulties, tremors and slow movement

|

* Exposure to carbon monoxide can cause hearing loss and may also increase the risk of noise-induced

hearing loss in industrial settings17

† For further information, see: “Effects of carbon monoxide poisoning”

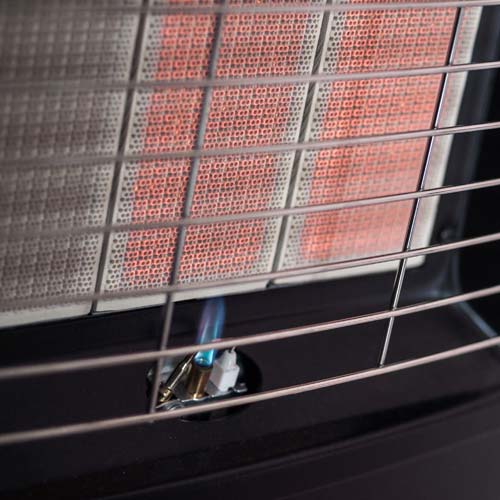

Portable LPG heaters should be avoided

Portable LPG heaters should be used with ventilation, e.g. an open window, and are not recommended for use in bedrooms.7 Signs

that an LPG heater or cooker may be burning inefficiently, which is associated with increased carbon monoxide formation,

include black marks on the heater around the flame, flames with orange or red tips* or unusual sounds during use.7 The

Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority (EECA) of New Zealand regards portable LPG heaters as the most expensive

form of heating available; informing patients of this may convince them to change heating sources and therefore reduce

their risk of carbon monoxide poisoning.18 In addition, portable LPG heaters can also cause or exacerbate

respiratory illnesses and asthma as they release nitrogen dioxide and water vapour, which increases growth of moulds and

dust mites.19

* Except for flame-effect heaters which are designed to appear this way

There can be a wide range of potential causes of non-specific symptoms associated with carbon monoxide exposure, such

as headache, dizziness, loss of balance, mood changes, difficulty concentrating, memory loss or visual disturbances (Table 2).

Differential diagnoses could include a variety of neurological, infectious or endocrine conditions. However, the

possibility of carbon monoxide poisoning should always be considered.

Assessing the likelihood of carbon monoxide poisoning begins with establishing if there is a potential source (Table

1) and identifying whether the patient’s symptoms have a pattern of onset or worsening consistent with exposure to

that source. In published cases, people with repeated exposure to carbon monoxide typically experience worsening of symptoms

such as headache in the hours after the exposure starts, and symptoms reduce within hours after leaving the source.4 A

carbon monoxide detector installed at a patient’s home* can provide evidence of a source of exposure. If potential

exposure at work is suspected, workplaces can arrange for employees to wear portable carbon monoxide detectors or have

other assessments carried out to establish whether safe working levels of carbon monoxide have been breached, with guidance

from Worksafe New Zealand.7

A definitive diagnosis of carbon monoxide poisoning can usually only be made after a source is eliminated, resulting

in resolution in the patient’s symptoms.

A simple four-letter acronym which can guide questioning is COMA:15

- Co-habitants or companions: Do other people living at the same address or at the same workplace have

similar symptoms? This could also include pets with signs of lethargy, difficulty walking or loss of balance.

- Outside or away: Do symptoms improve when outdoors or away from the normal place of work or residence

for a number of hours?

- Maintenance: What sources of heating are used, are gas heating or cooking facilities or fireplaces

well maintained and regularly serviced?

- Alarm: Is there a carbon monoxide alarm in the house or workplace?

* Available at hardware stores for approximately $60-$70. Some smoke alarms also detect carbon

monoxide.

Patterns of symptoms may be useful for diagnosis

There is no single symptom which is diagnostic for carbon monoxide exposure.10 Headache is commonly reported,

however, there are no specific characteristics of headache caused by carbon monoxide exposure which can help diagnosis.16 Nausea

or fatigue often accompanies headache with carbon monoxide exposure, but can also indicate migraine or many other causes.4

Patterns which could indicate exposure to carbon monoxide include symptoms which only occur:

- After arriving home or during the evening (if the source is at home)

- During the course of work (if the source is at work)

- During winter, e.g. due to use of a heater which emits carbon monoxide

- After moving to a different house or using a different form of heating

Patients exposed to low levels of carbon monoxide over a long period are unlikely to show any obvious signs on physical

examination. Cherry coloured skin or lips was previously considered a tell-tale sign of carbon monoxide poisoning, however,

it is not a reliable diagnostic sign as it is very rare and typically only occurs after exposure to very high levels or

post-mortem.4

Testing for low-level exposure may be difficult

Testing carboxyhaemoglobin levels forms part of diagnosis during emergency management of carbon monoxide poisoning (see:

“Emergency management of carbon monoxide poisoning”). However, this is likely to be less useful and more difficult to

interpret in patients with repeated low-level exposures, as carboxyhaemoglobin levels will not be as elevated as in an

acute poisoning event, and the delay between exposure and drawing blood for analysis means that test results will give

falsely low readings. Detecting low-level exposure in people who smoke is further complicated by the fact that smoking

results in the formation of carboxyhaemoglobin, with levels up to 9% classified as the upper limit of the reference range

for smokers, compared to 1.5% for non-smokers.20

Pulse oximetry is not useful for detecting carbon monoxide exposure: Standard pulse oximeters use two

wavelengths of light to determine oxygen saturation. These are unable to differentiate between haemoglobin bound to oxygen

and haemoglobin bound to carbon monoxide (carboxyhaemoglobin). Therefore, they are not useful for the assessment of carbon

monoxide poisoning as they will give a falsely elevated reading of oxygen saturation.21 Newer pulse oximeters

have been developed using additional wavelengths of light which detect carboxyhaemoglobin, however, these are not widely

available.

If low-level exposure to carbon monoxide is suspected and a potential source identified, develop a plan for the patient

to avoid future exposure, such as switching to an alternative form of heating.

For patients with repeated low-level exposures, it would be reasonable to expect improvement in most symptoms within

the first days of avoidance. However, some patients may have ongoing symptoms if exposure has resulted in underlying neurological

damage, such as problems with vision, hearing loss or tremors.4, 12

General Practitioners are required to report suspected exposures to the Medical Officer of Health via the Hazardous

Substances Disease and Injury Reporting Tool in the Practice Management System (PMS; see: “Notifying cases

of suspected carbon monoxide poisoning”). Contact your local Public Health Unit directly to report the exposure if your practice does

not have access to the tool. Patients with suspected exposure can be reported based on clinical suspicion and confirmation

of exposure is not required when submitting a notification.22 Advise patients to discuss potential exposures

in the workplace with their employer.

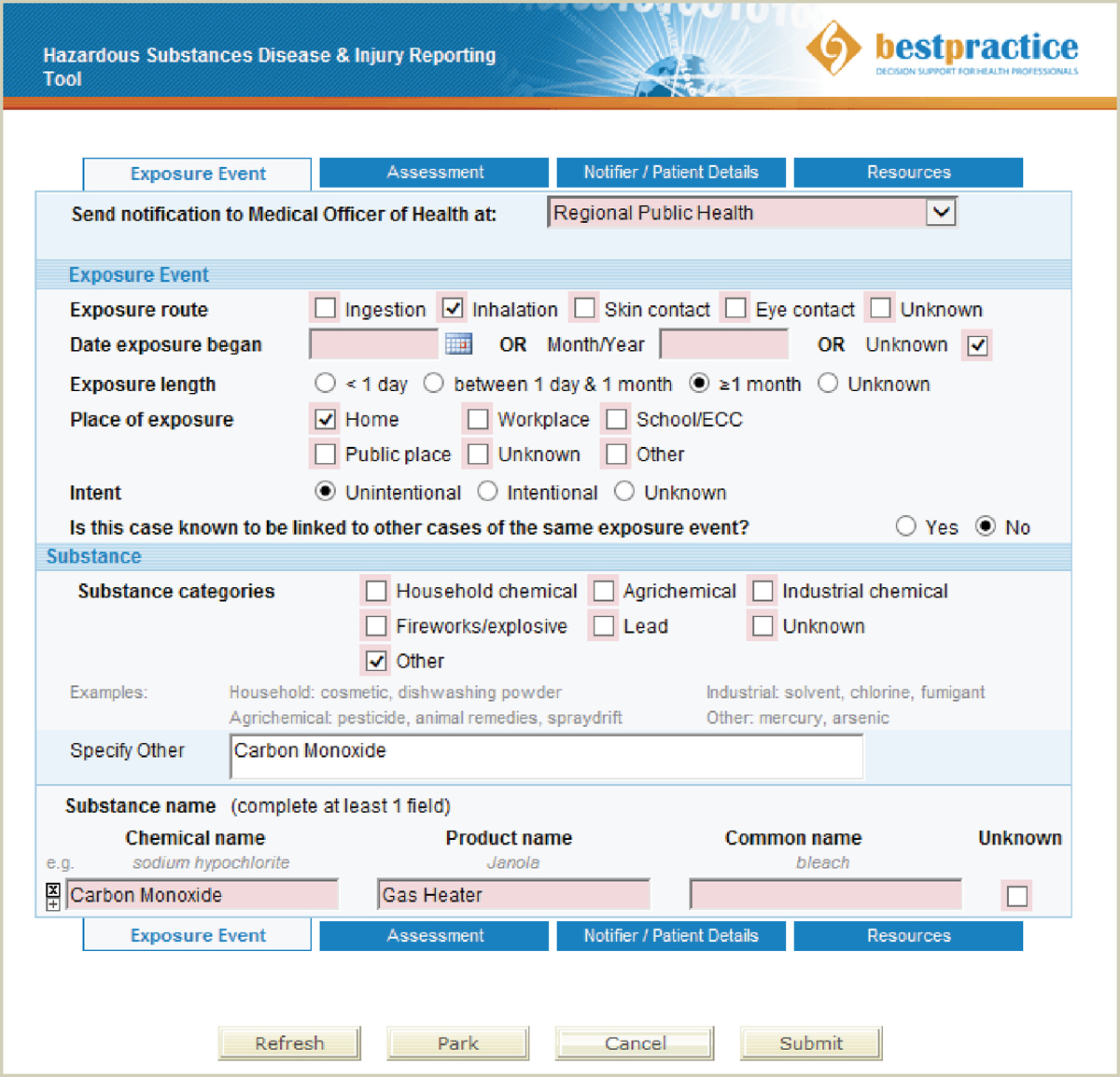

Notifying cases of suspected carbon monoxide poisoning

General Practitioners are required by law to report cases of suspected carbon monoxide poisoning, preferably using the

Hazardous Substances Disease and Injury Reporting Tool; this is available via MedTech and the MyPractice and Profile PMS

systems.23 In MedTech, go to:

- "Module List"

- "Hazardous Substances & Lead Notifications"

- "Hazardous Subs & Lead Notifications"

The notification tool will show three tabs for clinicians to complete: “Exposure Event”, “Assessment” and “Notifier/Patient

Details”. In the “Substance” category on the “Exposure Event” tab, carbon monoxide poisonings should be entered as “Other”

with carbon monoxide poisoning specified in the text box below.

This tool will notify the local Public Health Unit (PHU) and Medical Officer of Health about a potential exposure; the

PHU may take further action such as investigating further or forwarding notifications to Worksafe New Zealand.24

For further information on hazardous substances disease and injury notifications, see:

www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2016/May/e-notification.aspx

* Reporting cases of carbon monoxide poisoning to the Medical Officer of Health is required under Schedule 2 of the

Health Act 1956, as it is an example of poisoning arising from chemical contamination of the environment.25 It

is also required in the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996 under Section 143.26

Figure 1: An example of reporting carbon monoxide poisoning in the Hazardous Substances Disease and Injury Reporting Tool

For further information about this module, see:

www.bestpractice.net.nz/feat_mod_HSDIRT.php