Stomach cancer disproportionately affects Māori

Stomach cancer is the 11th most common cancer in New Zealand, and the eighth most common cause of cancer deaths.1 One

in 110 people will be diagnosed with stomach cancer during their lifetime.2 The vast majority of these cases

are sporadic. However, in about 1% of cases, there is a genetic predisposition to hereditary diffuse gastric cancer, an

autosomal dominant cancer syndrome caused by germline mutation of the CDH1 gene.2 CDH1 is

a tumour suppressor gene that codes for the cell adhesion protein, E-cadherin. Carrying an abnormal CDH1 gene

confers a lifetime risk of up to 70% for developing stomach cancer.2, 3 Female carriers also have an approximately

40% lifetime risk of developing lobular breast cancer.2

Several Māori families in New Zealand have had a long history of developing and dying from stomach cancer at an early

age. However, it was only in the 1990s that scientists from the University of Otago identified the gene that caused the

stomach cancer within these families.3, 4 It is now estimated that approximately 13% of all advanced diffuse

gastric cancer cases in Māori can be attributed to germline CDH1 mutations.2 The incidence and

mortality of stomach cancer is three times greater in Māori compared with non-Māori in New Zealand.5

Identifying the genetic cause

Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer is caused predominantly by mutations in the CDH1 gene, with a small number

of additional families outside New Zealand having CTNNA1 mutations.6 It is thought that an abnormal

E-cadherin protein results in some cells in the stomach and breast being displaced from the epithelial plane, causing

poorly regulated cell growth.

Inheritance of the CDH1 gene is autosomal dominant, meaning that a biological child of a carrier has a

50% chance of getting the gene, and consequently a 70% risk of developing stomach cancer.2 There are about

18 different CDH1 mutations in the New Zealand population affecting several hundred people, the majority

of whom are Māori.2

To watch a video on how the CDH1 gene mutation was identified, see:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=iqLPdcvHBvE

Key facts about hereditary diffuse gastric cancer:

- Members of affected families most commonly develop cancer during their 20s to 40s, but there have been cases reported

from age 14 years. Genetic testing can occur anytime from age 16 years.

- There are no reliably sensitive surveillance methods for detecting early stomach cancer in patients with the CDH1 mutation.

Symptoms of stomach cancer, which can include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, weight loss and dysphagia,7, 8 often

present late in the disease, by which time a cure is unlikely. Therefore, prophylactic gastrectomy should

be considered in the patient’s early 20s, but this is an individual decision.9

- Gastric endoscopic surveillance can provide some reassurance for the patient until a prophylactic gastrectomy is performed,

but this will not reliably detect cancer.10 Surveillance is offered from age 16 years.

- Since surgery has a major impact on quality of life, patients need to be well informed, well prepared and the timing

should be right in terms of education, work opportunities or other plans or circumstances, e.g. pregnancy;

recovery from surgery can take three to six months or longer.

- There may be a dormant period in which the cancer does not spread. This may explain why most family members are found

to have early stage tumors (T1a N0) at prophylactic gastrectomy. However, if they go on to develop diffuse

gastric cancer, the prognosis is poor with less than 10% having curable disease.

- Females are also at increased risk of developing breast cancer. These are lobular cancers and can be difficult to

detect by imaging or examination because the cells do not form a mass. Current screening guidelines include an annual

MRI, which can be combined with a mammogram and ultrasound from age 30 years. Annual breast self-examination and breast

care awareness are essential.

- To identify families who would benefit from genetic screening, a family history should be taken for all Māori diagnosed

with gastric cancer. Genetic testing for a CDH1 mutation should be considered for all patients with a family

history of diffuse gastric cancer and/or lobular breast cancer and for all patients aged <50 years with diffuse gastric

cancer (Figure 1).

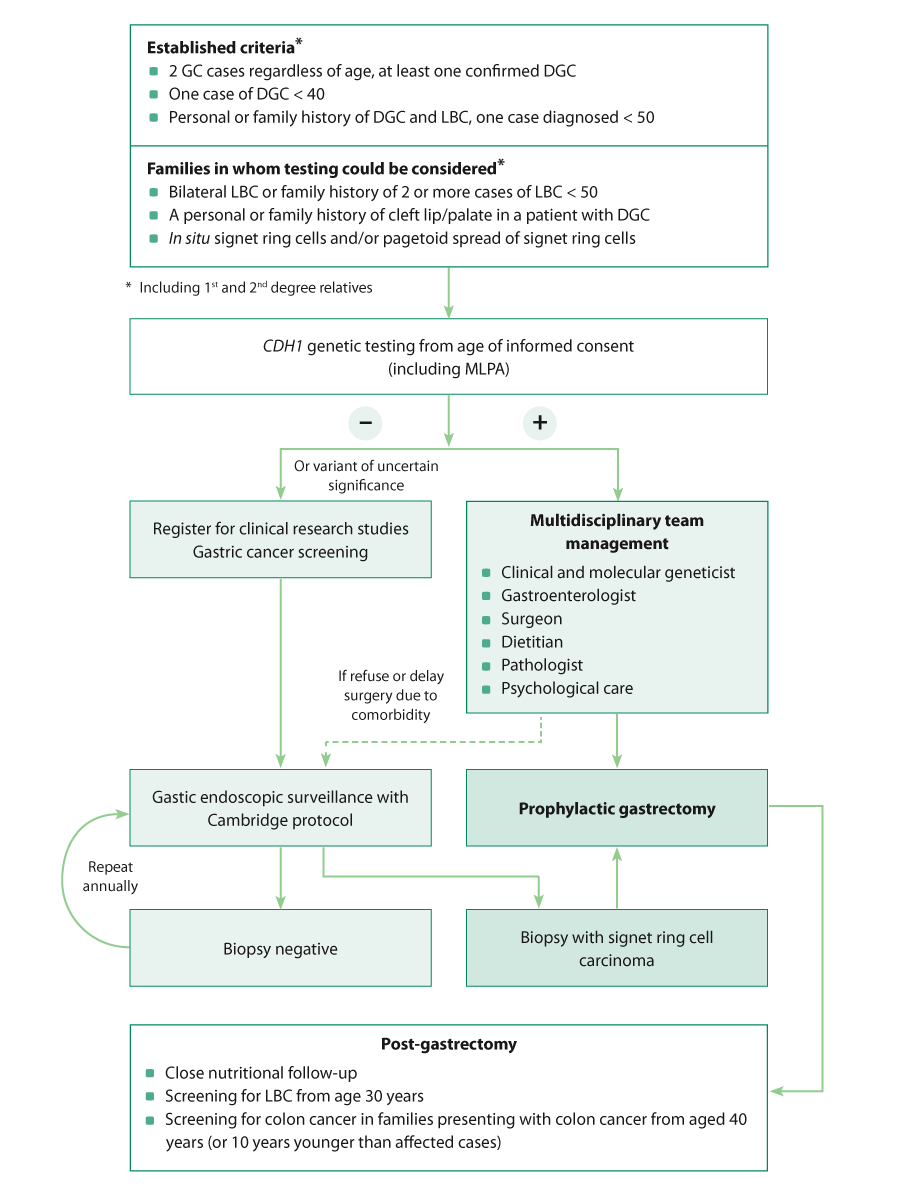

Figure 1: Algorithm for managing patients with a personal or family history of

diffuse gastric cancer, adapted from van der Post et al, 2015.9

GC = gastric cancer, DGC = diffuse gastric cancer, LBC = lobular breast cancer, MLPA = multiplex-ligation probe amplification.

Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer is initially asymptomatic, and there are no reliable surveillance methods, therefore

prophylactic total gastrectomy is the key management intervention for patients who have tested positive for the CDH1 gene

mutation.9 By the time symptoms develop, it is often too late for a cure.

Pathological examination after a prophylactic gastrectomy often finds patients to have multiple (≥ 100) small spots

(foci) of signet ring cell carcinoma within the stomach, that are under a millimeter in diameter.

Gastric endoscopic surveillance is undertaken while patients are awaiting surgery (or have deferred the decision). This

can provide some reassurance to patients and larger foci may be detected, but it is not a reliable long-term surveillance

method.

For full clinical guidelines on managing patients with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer, see:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4453626

Gastrectomy surgery and recovery

The surgery that is performed is a total gastrectomy with a Roux-en-Y reconstruction. Proximal resection must be within

the distal oesophagus to ensure that no stomach mucosa is left behind. There is generally no need for a radical lymph

node dissection as most tumours are T1a N0. If the stomach looks abnormal on gastric endoscopy or biopsies are positive

for cancer, a more radical operation may be needed.

There is significant morbidity associated with the operation. Short-term morbidity revolves around the surgery itself,

anastomotic leaks and learning to eat again. Long-term morbidity is related to nutrition and quality of life. As there

is no storage capacity from the stomach, patients initially need to eat little and often (e.g. six to eight small meals

per day and snacks) and usually require support from a dietitian. Over time, the oesophagus/intestine junction grows into

a pouch which can accommodate larger meals.

Eating too much or too quickly can cause abdominal pain. Dumping syndrome can occur; this is where rapid emptying of

food, particularly sugars, into the gastrointestinal tract causes symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhoea and sweating.

Patients can also experience lactose intolerance, fat malabsorption and steatorrhoea. Recovery is individual, however

in most cases symptoms resolve (or become manageable) within six months to one year following the surgery.

There is limited information about vitamin and mineral requirements following a gastrectomy. Although gastric bypass

surgery for managing obesity has some differences to a total gastrectomy in that a portion of the stomach remains, nutritional

deficiencies may share some similarities:11

Fat is the most difficult nutrient to absorb. Following a gastrectomy there is reduced time that food is

mixed with bile and pancreatic juice. This may lead to reduced digestion of fat, resulting in bacteria breaking down the

fats and releasing gas/flatus and steatorrhoea. The diagnosis is based on history of a layer of oil in the toilet pan,

diarrhoea, post-prandial loose bowel motions and cramping abdominal pain, and may be confirmed with a faecal elastase

test. This may lead to overall nutritional and vitamin deficiencies. Treatment is with pancreatin 300 mg (Creon 25,000),

two to three capsules with each meal, taken at the beginning and during the meal.

Fat soluble vitamins – vitamin A, D, E, K are generally easily absorbed, however if the patient has steatorrhoea

deficiencies of these vitamins can arise. This may manifest with night blindness (vitamin A) and bruising (vitamin K).

Oral multivitamins may be useful.

Protein and sugar malabsorption are less frequent as these nutrients are more easily absorbed. Hair loss,

skin and nail changes are early signs of protein deficiencies.

Calcium, vitamin and protein absorption occurs mostly in the duodenum. As this is bypassed during the gastrectomy

operation, absorption may be reduced. Therefore, long-term multivitamins are required morning and evening. Calcium deficiencies

only become apparent in later life. However, replacing oral calcium is not considered beneficial as it appears to deposit

in the arteries. Therefore, patients are recommended to undertake regular weight bearing activity and take multivitamins

containing vitamin D; a walk in the sun each day would contribute to both requirements.

Vitamin B12 cannot be absorbed without a stomach as intrinsic factor is not secreted. Regular vitamin B12

injections are required (hydroxocobalamin 1000 micrograms, intramuscular injection, administered every one to three months).

Iron in food is poorly absorbed without a stomach as iron needs to be converted to a useable form by stomach

acid. Oral iron supplements are easily absorbable but are often not well tolerated. Iron infusion every six months to

yearly may be an alternative.

For further information on dietary advice, recipes and patient experiences post-gastrectomy, see:

www.nostomachforcancer.org

Extensive research is being undertaken at the University of Otago to develop a chemo-preventative treatment for people

with the CDH1 mutation. A “synthetic lethal” approach is being used to exploit cellular vulnerabilities that

arise with the loss of the tumour suppressor gene, CDH1. These vulnerabilities are likely caused by the cell

membrane disorganisation observed in mutant CDH1-deficient cells. A successful pharmacological agent will

render CDH1-deficient cells unviable and induce cell death, while having minimal effect on normal CDH1-expressing

cells. As a result, these medicines could be used to reduce or eliminate the risk of gastric cancer in families who carry

the gene.

There are two primary aims for current research:

- Develop new models of hereditary diffuse gastric cancer with improved representation of in vivo disease.

Three new models of increasing complexity are currently in use or being developed:

- Gastric cancer isogenic cell lines with and without CDH1 mutations

- Gastric organoids (miniature 3D stomach structures), cultured from murine stem cells

- A transgenic mouse model for in vivo experiments

- Use these models to screen drug libraries for potentially therapeutic compounds, with the eventual goal of developing

a chemo-preventative treatment.

So far, this research has yielded promising results, with thousands of compounds already screened in the isogenic cell

lines and many hits identified. Organoid development and optimisation is largely complete, and drug screening on this

more complex model is set to begin shortly. With these novel pre-clinical models and robust screening systems, there is

much confidence and optimism among researchers around future results and their potential impact. With the current progress,

it is envisaged the first human trials could start within five years.

“My Passport”: information for whānau

New Zealand researchers, Dr Parry Guilford and Mr Jeremy Rossaak have developed a document called “My Passport”, which

is soon to be published. It incorporates information for patients and whānau about genetic testing, pre-operative, surgical,

post-operative and long-term care. This document has been written to help patients and their whānau with hereditary gastric

cancer understand their condition and participate in decisions about their care. It is initially expected to be published

on the websites listed below, as well as the University of Otago Centre for Translational Cancer Research website, the

Bay of Plenty’s DHB website and copies provided to Kimihauora Health Clinic.

See: www.nostomachforcancer.org and

www.hereditarydiffusegastriccancer.org