Benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine-like hypnotics* and

anxiolytics are medicines that bring about a state of sedation,

drowsiness, relaxation and impaired memory formation,

depending on the drug and formulation used. Benzodiazepine-like

hypnotics are often referred to as z-drugs due to the

alliteration in their naming (zopiclone, zolpidem, zaleplon) and

indication as hypnotics. Zopiclone is the only z-drug available

in New Zealand. Benzodiazepines are Class C controlled drugs;

zopiclone is not a controlled drug.

* Also referred to as benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BZRAs)

New Zealand pharmaceutical dispensing data shows that in the 12 months from October, 2019, to September, 2020:1

- Zopiclone was the most widely used funded hypnotic medicine – the number of people dispensed zopiclone

was greater than the total number of people dispensed any benzodiazepine

- Zopiclone was the 14th highest volume medicine dispensed with 118 dispensed prescriptions per 1,000 registered patients

- Lorazepam and diazepam were the two highest volume benzodiazepines dispensed, with 41 dispensed prescriptions per 1,000 registered patients and 23

dispensed prescriptions per 1,000 registered patients, respectively

- Benzodiazepine and zopiclone use were particularly prevalent in older people – approximately 10% of people aged 75 years and older were regularly dispensed* these medicines

*Defined as having a prescription dispensed in at least three out of four quarters

Large volumes of zopiclone and benzodiazepines are being dispensed

Analysis of New Zealand dispensing data shows that there are many patients being prescribed large quantities of benzodiazepines

and zopiclone (for any indication). It is uncertain to what extent these medicines are being used by the patients for whom

they are prescribed, as opposed to being stockpiled, shared or even on-sold.

Treatments for insomnia: zopiclone and temazepam

Zopiclone, temazepam and triazolam are short-acting hypnotic medicines indicated for the treatment of insomnia (Table 1).

In the 12 months from October, 2019 to September, 2020, over half of patients were dispensed more zopiclone or temazepam

than necessary for one four-week course. While patients should only take zopiclone or benzodiazepines

short-term for the treatment of insomnia, there are no clear clinical guidelines regarding an appropriate medicine-free

interval before another short course is tried. Patients dispensed a large volume of tablets in one year may have been

taking them on an as required ongoing basis throughout the year or over several short courses (see: “Who

in the patient population is using zopiclone?”).

N.B. In practice, significantly shorter courses, e.g. 10 tablets, are more likely to be prescribed; some patients may take a

higher or lower dose (e.g. two tablets per night or half a tablet per night).

| Zopiclone tablets: |

< 30 |

30 – 179 |

≥ 180 |

| % patients in 2019/2020 year: |

39% |

39% |

21% |

N.B. In practice, significantly shorter courses, e.g. 10 tablets, are more likely to be prescribed.

| Temazepam tablets: |

< 30 |

30 – 179 |

≥ 180 |

| % patients in 2019/2020 year: |

37% |

40% |

22% |

Who in the patient population is using zopiclone?

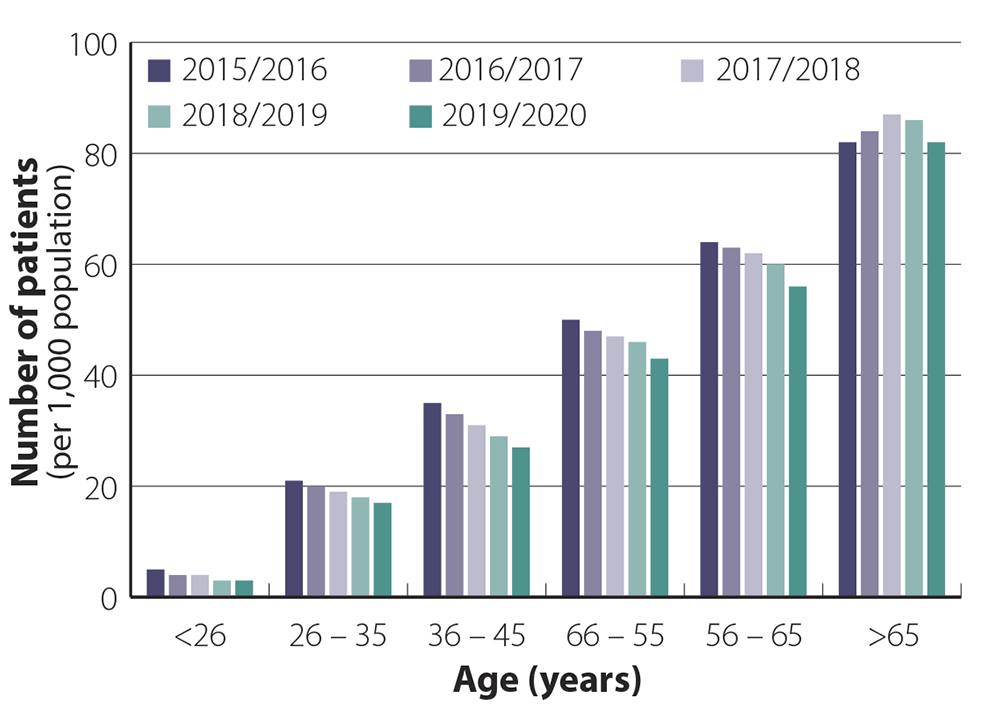

Zopiclone prescribing is not just in older people

Most general practitioners in New Zealand are likely to have patients in their practice who have been taking hypnotic

medicines long-term. These patients are usually older, e.g. aged over 65 years, and were initially prescribed hypnotic medicines

many years ago but have been unable to discontinue treatment. Dispensing data reflect this, showing that the highest dispensing

rates are in people aged > 65 years, the group who is at the greatest risk of harm from adverse effects such as falls

(see: “Adverse effects of hypnotics can range from subtle to serious”) (Figure

1).

However, dispensing data also show that many younger people in New Zealand are prescribed zopiclone, although in lower

volumes than the older population.1 These data indicate that people start to seek help for sleeping from age

late 20s onwards. If younger patients become dependent on using hypnotic medicines for sleep, they face a large cumulative

risk from ongoing use as they get older. Dispensing across different age groups has remained relatively steady over the

last five years.

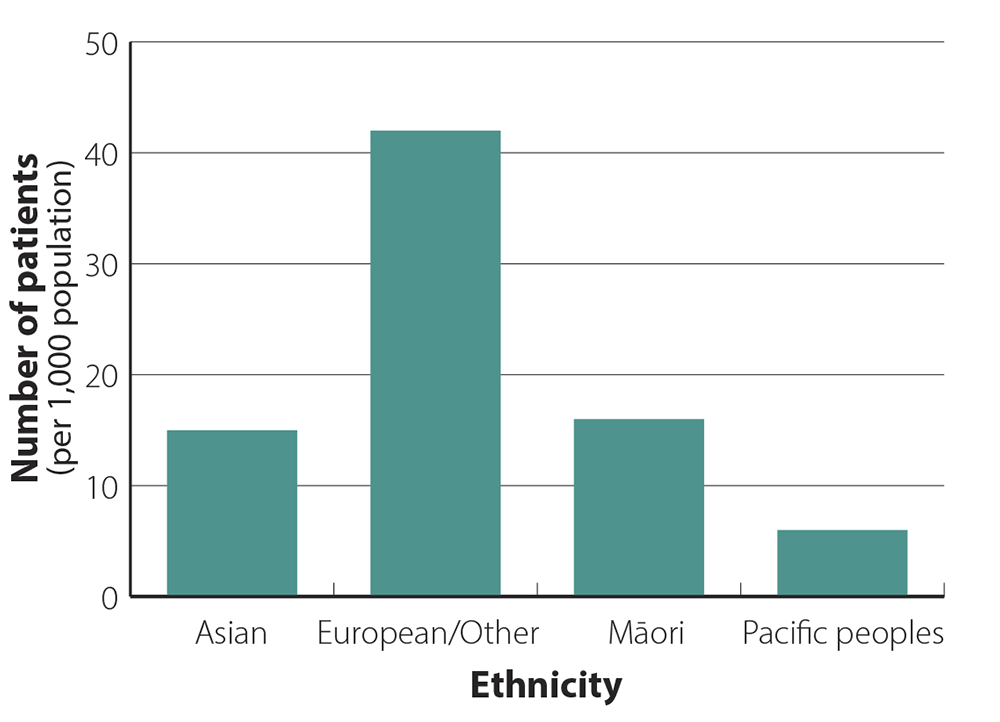

Zopiclone dispensing is highest in people of European/Other ethnicity

The zopiclone dispensing rate in the 12 months from October, 2019 to September, 2020, was three times higher in

people of European/Other ethnicity than Māori and Asian peoples, and seven times higher than Pacific peoples (Figure

2). Differences

in acceptability of pharmacological treatments for insomnia, access to healthcare, and

other undefined inequities may contribute to these differences.

Figure 1. Patients per 1,000 population dispensed at least 20

tablets of zopiclone in a year across different age bands

from 2015/2016–2019/2020 (12 months from October to September).

|

Figure 2. Patients per 1,000 population dispensed at least 20 tablets of zopiclone in the 12 months from

October, 2019 to September, 2020, by ethnicity.

|

Table 1. Key prescribing information for benzodiazepines and zopiclone approved in New Zealand for the treatment of insomnia and anxiety.2

| Key medical indication for use in primary care* |

Dose formulation |

Half life† |

Recommended dose for healthy adults** |

| Insomnia‡ |

|

|

|

|

Temazepam |

10 mg tablets |

short |

10 – 30 mg half an hour before bedtime |

|

Triazolam |

125 and 250 microgram tablets |

short |

125 – 250 micrograms at bedtime†† |

|

Zopiclone |

7.5 mg tablets |

short |

3.75 – 7.5 mg at bedtime |

| Anxiety‡ |

|

|

|

|

Alprazolam [section 29, unapproved medicine] |

500 microgram tablets |

short |

0.5 – 4.5 mg daily, divided doses |

|

Diazepam |

2 mg and 5 mg tablets |

long |

15 – 30 mg daily, divided doses |

|

Lorazepam |

1 mg and 2.5 mg tablets |

medium |

1 – 4 mg, daily, divided doses |

Fully Funded

Fully Funded

Partly Funded No circle = not funded

Partly Funded No circle = not funded

* Clonazepam is not included in this table as its approved indication is for the treatment of epilepsy. However,

in practice some clinicians use clonazepam to treat anxiety. It is a long-acting benzodiazepine; NZF does not list a dose for use in anxiety.

† Half-life definitions – short: less than 12 hours, medium: 12 – 24 hours, long: >24 hours. Half-life is likely to be

longer in older or frail patients, or those with renal impairment. The use of benzodiazepines with long half-lives is not recommended in older or frail patients.

** Older patients or those with co-morbidities such as renal impairment may require lower doses, often recommended

as half the normal adult dose, see NZF for further information

‡ Nitrazepam (indicated for insomnia) and oxazepam (indicated for anxiety and acute alcohol withdrawal)

have been discontinued and may have limited availability (see: “Oxazepam and nitrazepam have been discontinued”).

†† NZF recommends a treatment duration of no more than ten days

Table 2. The % (number) of patients dispensed zopiclone, temazepam or triazolam in New Zealand in the 12 months from October,

2019 to September, 2020, by volume of tablets.1 N.B. % data are expressed as a proportion of all patients dispensed that medicine.

| Number of tablets |

Zopiclone (7.5 mg) |

Temazepam (10 mg) |

Triazolam (125 microgram and 250 microgram tablets)* |

| < 30 |

39% (81,770) |

37% (7,178) |

22% (3,420) |

| 30–59 |

18% (38,045) |

19% (3,738) |

17% (2,677) |

| 60–89 |

9% (19,025) |

9% (1,827) |

11% (1,646) |

| 90–119 |

5% (10,707) |

5% (980) |

6% (893) |

| 120–149 |

4% (8,428) |

4% (833) |

5% (822) |

| 150–179 |

3% (5,965) |

2% (459) |

3% (516) |

| ≥ 180 |

21% (44,612) |

22% (4,348) |

36% (5,610) |

* Partly funded

Treatments for anxiety (and other indications): lorazepam and diazepam

Lorazepam and diazepam are medium and long-acting benzodiazepines, respectively, indicated for the treatment of anxiety

(short-term use only), acute alcohol withdrawal, status epilepticus, muscle spasm and as sedatives during

medical procedures. Lorazepam and diazepam are also indicated for the short-term treatment of insomnia, however, they

are not a preferred treatment (see: “Oxazepam and nitrazepam have been discontinued”). Dispensing

data show that approximately half of people received more than 30 tablets in the 12 months from October, 2019 to September,

2020, suggesting that long-term use is common (Table 3). As found with zopiclone and temazepam,

approximately 20% of people were dispensed ≥180 tablets of diazepam or lorazepam in the 2019/2020 year.

Oxazepam and nitrazepam have been discontinued

In August, 2020, the supplier announced the discontinuation of oxazepam (Ox-Pam), a short-acting benzodiazepine indicated

for the treatment of anxiety and alcohol withdrawal. PHARMAC was not able to find an alternative supplier; Ox-Pam is the

only approved brand of oxazepam in New Zealand. It is expected that supply of Ox-Pam will run out in July, 2021. Patients

who are currently using oxazepam will need to switch to an alternative benzodiazepine, which then may be able to be slowly

withdrawn.

Nitrazepam (Nitrados), indicated for insomnia, has also been discontinued and was delisted from the Pharmaceutical Schedule

on 1 January, 2021. No other brand of nitrazepam is being funded. Clinicians should review whether benzodiazepine treatment

is still clinically indicated; patients who use nitrazepam chronically should be transitioned to diazepam as it is less

likely to cause withdrawal symptoms due to having a long half-life, and then the diazepam slowly withdrawn.

The New Zealand Formulary contains dose equivalence data to assist in switching benzodiazepines, as well as

and guidance for benzodiazepine withdrawal: https://nzf.org.nz/nzf_2001

For further information on the oxazepam discontinuation, see: https://pharmac.govt.nz

For further information on the nitrazepam discontinuation, see: https://pharmac.govt.nz

Table 3. The % (number) of patients dispensed diazepam or lorazepam in New Zealand in the 12 months from October, 2019

to September, 2020, by dose and volume.1 N.B. % data are expressed as a proportion of all patients dispensed that medicine.

| Number of tablets |

Diazepam (2 mg) |

Diazepam (5 mg) |

Lorazepam (1 mg) |

Lorazepam (2.5 mg) |

| < 30 |

53% (12,279) |

46% (9,885) |

54% (40,005) |

46% (893) |

| 30–59 |

17% (3,833) |

15% (3,246) |

17% (12,546) |

15% (287) |

| 60–89 |

7% (1,651) |

7% (1,519) |

8% (5,838) |

8% (149) |

| 90–119 |

3% (778) |

4% (784) |

4% (2,783) |

4% (76) |

| 120–149 |

2% (536) |

3% (646) |

3% (2,077) |

3% (68) |

| 150–179 |

2% (348) |

2% (392) |

2% (1,293) |

2% (43) |

| ≥ 180 |

16% (3,610) |

23% (4,871) |

13% (9,992) |

22% (438) |

- Benzodiazepines or

zopiclone should only be prescribed short-term for conditions where the benefits of treatment outweigh the risks,

with regular review of use, and non-pharmacological strategies continued alongside

- If a hypnotic is indicated,

choose a short-acting preparation (i.e. zopiclone, temazepam or triazolam) and prescribe this at the lowest effective

dose for a short duration (e.g. five to ten days)

- Benzodiazepines are

not a first-line pharmacological treatment for anxiety; short-term treatment may be appropriate in some situations

- Adverse effects can

lead to adverse clinical outcomes, such as an increased risk of falls and motor vehicle accidents. Particular care

should be taken when prescribing these medicines to older people or those with frailty.

Prescription of benzodiazepines and zopiclone needs to be carefully considered as patients may perceive that the rapid

symptom relief that is often gained when using these medicines outweighs any adverse effects and risks. Patients may be

less willing to try other treatments that are not as instantly gratifying, such as non-medical interventions for insomnia

or anxiety, but these are likely to be safer and more appropriate in the long-term.

Prior to starting the medicine, patients should be given information about the risks and benefits of treatment, including

adverse effects and the potential for dependence; ensure they understand that these medicines are intended for short-term

use only (i.e. not taken on a regular basis) and non-pharmacological strategies should be continued alongside. In patients

with severe symptoms, medicines may be used short-term while non-pharmacological measures are implemented. Benzodiazepines

or zopiclone should only be prescribed for limited indications, in small quantities, with regular review of use. Prescribers

should be vigilant for drug-seeking behaviour, such as early requests for repeat prescriptions or claims of lost prescriptions.

For further information on misuse of prescription medicines, see: https://bpac.org.nz/2018/misuse.aspx

For information on how to discontinue benzodiazepines or zopiclone treatment in patients who have been using

these medicines long term, see: https://bpac.org.nz/2021/benzo.aspx

For the treatment of insomnia

Benzodiazepines and zopiclone are not preferred treatment options, because:

- Cognitive-behavioural approaches (e.g. sleep hygiene and sleep restriction) have high levels of efficacy, are supported

by a good evidence base, and achieve better outcomes in the long-term.3, 4 However, these benefits can be difficult

to communicate to patients who are after a “quick fix”.

- Benzodiazepines and zopiclone are known to alter sleep architecture, with a reduced amount of time spent in slow wave

sleep, reducing overall sleep quality compared to the equivalent duration of sleep achieved by cognitive-behavioural approaches 5

If a hypnotic is being considered, because other interventions have been unsuccessful, a short-acting preparation should

be chosen (i.e. zopiclone, temazepam or triazolam) and prescribed at the lowest effective dose for a short duration (e.g.

preferably five to ten days, but can be used for up to four weeks*). Non-pharmacological strategies should be

continued alongside, e.g. sleep hygiene.

*With the exception of triazolam which is recommended for a maximum of ten days in the NZF

For further information, see: www.bpac.org.nz/2017/insomnia-1.aspx and www.bpac.org.nz/2017/insomnia-2.aspx

For the treatment of anxiety

Benzodiazepines:

- Are not recommended as a routine treatment for generalised anxiety disorder or social anxiety disorder; short-term treatment

may be appropriate in some situations6, 7

- Are not recommended for the long-term treatment of panic disorder – SSRIs are recommended first-line if pharmacological

treatment is indicated.6 Benzodiazepines may be considered short-term if other pharmacological strategies are

ineffective or while the SSRI is taking effect, or for the acute management of panic attacks.8

- Are not recommended for the prevention of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) –trauma-focused cognitive behavioural

therapy reduces the number of adults meeting the criteria for diagnosis of PTSD in the month following a traumatic event;

there is no consistent evidence that any pharmacological treatments are effective in preventing PTSD9

In addition to psychological support and counselling, pharmacological treatment options for anxiety, depending on the

type of anxiety disorder, include SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressants, buspirone and benzodiazepines (short-term use only).

Prescribing benzodiazepines as a first-line treatment option, even for short-term benefit, can lead to patient reliance

on the medicine for anxiety management, and may deter commitment to later psychological interventions due to the comparatively

delayed symptom relief. If prescribed, discuss these risks with patients and put in place a plan to minimise their occurrence,

e.g. only prescribing a short course or for intermittent treatment of an acute panic attack, with regular review.

Benzodiazepines are often prescribed on an “as needed” basis to reduce the risk of tolerance.10 However, irregular

dosing can lead to fluctuating blood levels that may aggravate anxiety; it may be preferable to encourage regular, rather

than as needed, use short-term to prevent panic attacks if other first-line treatment options are not recommended or tolerated.8,10

Adverse effects of hypnotics can range from subtle to serious

Benzodiazepines and zopiclone can cause a range of adverse effects, including:2, 11, 5

- Vertigo

- Muscle weakness

- Effects on cognition

- Dependency

- Increased risk of dementia and possible increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease

- Sleep automatism (in the case of z-drugs), including food binging, and even driving, while still asleep or in a sleep-like

state

- Reduced libido

These adverse effects can lead to adverse clinical outcomes, such as an increased risk of falls and motor vehicle accidents.5,

11 Adverse effects of benzodiazepines on cognitive function appear to persist even after the medicine is stopped.

Concomitant use of benzodiazepines or zopiclone with opioids, alcohol, tricyclic antidepressants and bupropion, increases

the risk of adverse effects such as sedation and respiratory depression, which in turn increases the risk of falls, particularly

in older people, and fatal overdose. Other risks associated with using benzodiazepines or zopiclone and opioids or alcohol

include lack of judgement, sexual disinhibition and criminal activity.

Older or frail patients have reduced clearance of medicines from their body and are likely to need a lower dose of benzodiazepines

or zopiclone to minimise adverse effects, such as half the normal adult dose. Benzodiazepines with a long half-life should

be avoided due to an increased risk of falls with next-day drowsiness (Table 2). Particular care needs

to be taken with diazepam, which has both a long half-life and active metabolites.5, 12

To check for interactions between benzodiazepines or zopiclone and other medicines, see: https://www.nzf.org.nz/nzf_1